Pain in dementia: A multi-modal approach to assessment and management

Cathy Knight

Cathy Knight

Admiral Nurse, LOROS Hospice,

Groby Road, Leicester

Karen Harrison Dening

Head of Research & Publications,

Dementia UK

People with dementia may be in just as much pain as other patients but less able to communicate how they are feeling. This article will use an unfolding case study approach to critically examine the process of pain assessment and management in a person with dementia

More people are living longer in old age, so we are seeing an increase in both the prevalence and incidence of age-related conditions such as dementia. ‘Dementia’ describes a syndrome – a collection of symptoms, including a decline in memory, reasoning and communication skills, and a gradual loss of skills needed to carry out daily living activities.1 These symptoms are caused by structural and chemical changes within the brain as a result of neurodegenerative changes, including tissue destruction, compression, inflammation, and biochemical imbalances.

We are also seeing an increase in the numbers of people living long enough to develop the multiple co-morbidities associated with old age.2 Often such conditions will have pain as one of their most significant symptoms.

PAIN IN DEMENTIA

There is widespread evidence that untreated pain in people with dementia is common,3-5 and that they often have inequitable access to effective pain assessment and management.3 Retrospective interviews with family carers indicate that significantly more patients with dementia experience pain in the last 6 months of life compared with those with cancer (75% vs. 60%).3,5 Untreated pain is a major contributor to reduced quality of life for people with dementia, and can lead to a range of complications including delirium,6 inappropriate sedation and use of antipsychotic medications,7 and increased confusion.8

The assessment and treatment of pain are particularly challenging due to the reduced ability of some people with advanced dementia to verbalise their pain and discomfort. Commonly used assessment tools are not reliable and are difficult to use, which can lead to symptoms being missed or misunderstood.9 How people with dementia express their physical distress can often be misinterpreted, and their symptoms attributed to their dementia. This is known as diagnostic overshadowing.10 So behaviours including aggression, agitation, wandering and low mood may be wrongly attributed to dementia rather than another underlying condition. This may contribute to poor pain management.4

Case study

Joan (not her real name) is an 82-year-old retired nurse who was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, the most common form of dementia,11 5 years ago, and is now in the moderate stage. She has also had osteoarthritis (OA) in her knees for the past 10 years, causing chronic pain.

Pain is defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage,12 and is categorised as either acute pain (less than 12 weeks’ duration) and chronic pain (of more than 12 weeks’ duration).13

Pain is not just a physiological experience but one that features both cognitive and emotional aspects,14 and is a very personal experience. Little is known about whether people with dementia experience pain in the same way as those without, due to the nature of the neurodegenerative processes of the dementia.15 However, if we accept that pain is influenced by such factors as mood, memory, culture, and environment then a person with dementia is no less likely to experience pain than anyone else, and it is more likely that the added complexity of their inability to articulate pain may increase their pain experience.

Case study

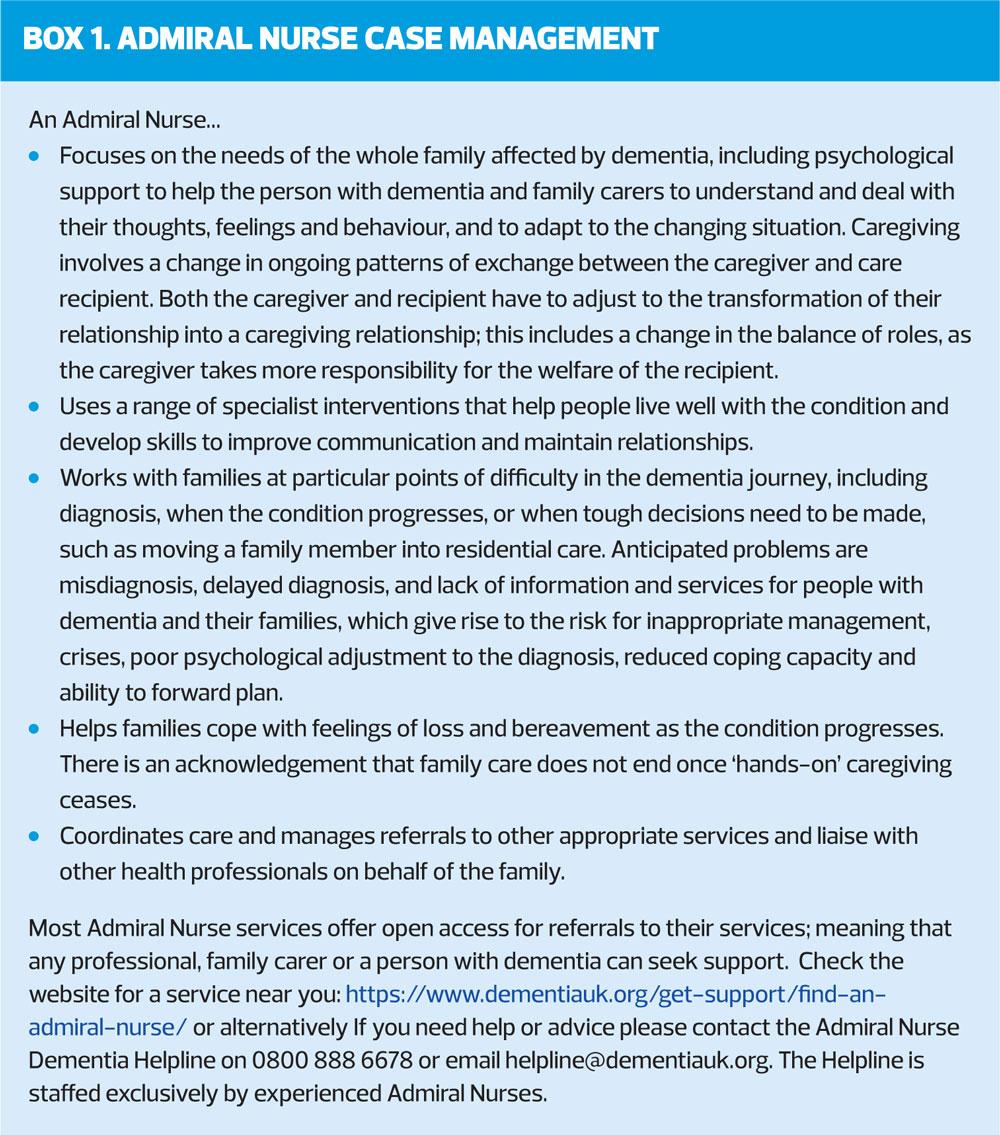

Joan is cared for by her husband, Allan, an 85-year-old retired engineer, who was finding it increasingly difficult to support Joan with washing and dressing. Joan was becoming aggressive and agitated, particularly first thing in the morning when Allan helped her to get out of bed and get dressed and it was becoming too much for him. Recently Allan employed a private care agency to provide personal care for his wife but since then Joan’s behaviour has worsened. Allan contacted his local Admiral Nurse Service (Box 1).

When first meeting Joan, the Admiral Nurse used Dementia UK’s 18 point assessment framework, covering areas such as physical and mental wellbeing of both the person with dementia and the carer.16 Through the assessment, it appeared that the behaviour experienced by both the care agency and Allan could be attributed to a further deterioration of Joan’s dementia.

Expressive aphasia

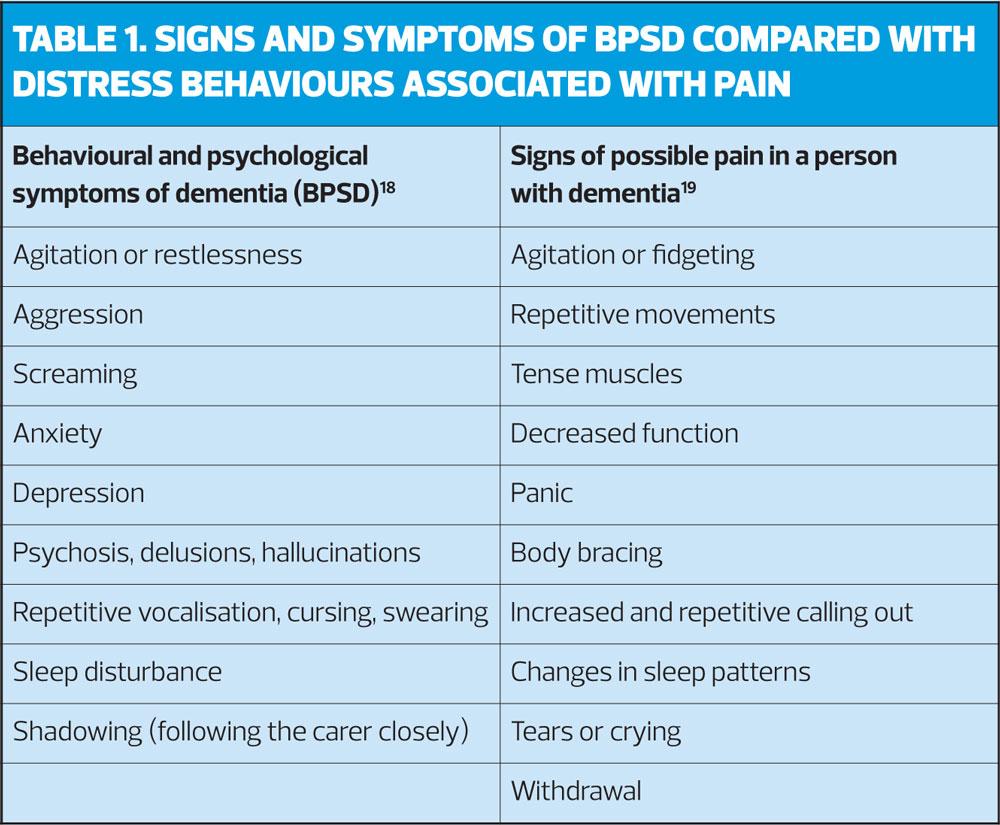

Older adults with dementia are a vulnerable group when it comes to pain assessment as difficulties with communication often lead to pain being missed.17 Pain in people with dementia often manifests as behavioural changes, which can be misinterpreted as the behavioural and psychological symptoms and signs of dementia (BPSD),18 such as agitation, resistive behaviour, sleep disturbance and screaming. These are not dissimilar to the signs and symptoms of distress relating to pain.19 (Table 1). Identifying that Joan had a history of osteoarthritis but was not currently taking any analgesia highlighted this as an area for further assessment.

Self-report is the gold standard for pain assessment, but in Joan’s case this was complicated by her expressive dysphasia. Dysphasia is an impaired ability to understand (receptive aphasia) or use (expressive aphasia) the spoken word, and may include impaired ability to read, write and use gestures.20 The most common causes are cerebrovascular disease, a space occupying lesion, head injury or dementia. Joan was unable to reliably communicate verbally her discomfort or pain. In addition, Allan reported that as a nurse, Joan had always adopted a stoic, ‘get on with it’ attitude and, as with many older people, accepted pain as a normal part of ageing.17 Consequently, when Allan was asked if he felt Joan was in pain he said that she wasn’t and he would know if she was.

Proxy reporting of pain in dementia by a family carer has sometimes been shown to be inaccurate.21 When Joan was first diagnosed with OA she was able to articulate and manage her pain independently. Later, as her dementia progressed and affected her use of language, she became unable to describe her pain, and it also affected her ability to self-medicate.

OBSERVATIONAL PAIN ASSESSMENT

There are numerous pain assessment scales, most of which rely on the person themselves to rate their experience of pain. However, where someone has advanced dementia or dysphasia, as in Joan’s case, self-report can be unreliable and invalid.17,22 Assessing pain in people with dementia becomes reliant on other techniques. These commonly include observation and measurement of expressed behaviours that are considered possible signs of pain including facial expressions (such as grimacing), vocalisation (including repeatedly calling out and moaning), guarding and tensing of muscles, withdrawal, agitation and fidgeting, and changes to sleep pattern and appetite.2 There are also several validated observational tools for assessing pain in people with dementia, such as, the Abbey Pain Scale and Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAIN-AD).23,24

Undertaking a holistic assessment, exploring not only signs and symptoms but also the impact that the pain was having on Joan helped to build a picture of her pain experience.

Case study

The Admiral Nurse used the Abbey pain scale as it is reliable,25 she had used it before, and felt it would be suitable for Allan and the caregivers to use.

Allan had not considered that Joan may have been in pain from her OA. The nurse also asked Allan and the caregivers if there were any times of the day that Joan’s behaviour was worse and advised them to keep a diary, which revealed that it was usually worse in the morning when the caregivers were helping her to get up and dressed. Allan also reported that Joan had not been sleeping well, tending to eventually settle in the early hours of the morning after long periods of restlessness and agitation. The caregivers then arrived at 7am to get her up just when Joan had finally been able to fall asleep. As they woke her and assisted her to get out of bed, walk to the bathroom and dress, this was when Joan became resistant, aggressive, distressed and shouted out. The Abbey Pain Scale completed at this time indicated a score of 12 (where 0 – 2 = no pain and >14 = severe pain).

Significantly, poor sleep, anxiety and fear can all impact on the experience of pain

Not only was Joan unable to articulate her pain but this was compounded by her inability to understand why she was being woken and got out of bed before she was ready. Joan may also have failed to recognise the caregivers or their actions and intentions as they attempted to wash and dress her. Thus the pain experience was heightened, perpetuating a cycle of fear and pain. However, the diary also revealed that Joan appeared to relax and was less agitated after a warm bath.

Case study

Joan had always been an active person and this remained so even as her dementia progressed. She would often repeatedly walk around the house and garden but on occasions would try to open the front door to leave. The risk this posed was something that Allan found very stressful but when he tried to get Joan move away from the door and to sit down, it often resulted in her becoming increasingly agitated and verbally aggressive towards him. The Admiral Nurse talked with Allan and helped him to reflect on how Joan used to manage the pain and discomfort from her OA before she developed dementia. Allan realised that Joan had always tried to remain active and that walking was something that she did every day, especially in the mornings, as a way keeping her joints mobile.

BEHAVIOURS THAT CHALLENGE

When Joan first began to exhibit challenging behaviours, it was assumed that it was due to the progression of her dementia, so the GP decided to prescribe an antipsychotic medication. However, as Joan’s behaviour was a result of pain and not a symptom of the dementia, there was little improvement, causing her instead to become drowsy during the day and at increased risk of falls. The Admiral Nurse discussed the pain assessment with Joan’s GP and the antipsychotic medication was subsequently discontinued in favour of pain medication.

Case study

The GP suggested commencing Joan on co-codamol, but Allan reminded him that Joan had been tried this previously, causing her to become very constipated, making her confusion worse and increasing her agitation.

PHARMACOLOGY AND PAIN

Older adults are likely to be more susceptible to side effects of medication, and the person with dementia is at risk of the consequences of polypharmacy.26 NICE recommends topical NSAIDs as a first line treatment for OA pain.27 In addition, Joan was prescribed regular paracetamol (1gm every 4-6 hours) as part of a multimodal approach. Often such medication is prescribed on an ‘as required’ basis but at Joan was unable to communicate her pain she was similarly unlikely to express her need for an analgesic.

Case study

Joan did well on a regime of topical diclofenac gel and regular paracetamol over the following three weeks. Allan and the caregivers reported a significant reduction in Joan’s agitation and that she appeared much more settled. Allan and the caregivers also said that repeated recordings on the Abbey Pain Scale showed a reduction in Joan’s observed pain scores.

A MULTIMODAL APPROACH TO PAIN

Analgesia is only one approach to the management of pain. Anxiety, poor sleep, discomfort and fear are examples of contributory factors that can intensify the perception of pain.14 Joan had a poor sleep pattern, probably due to discomfort, often falling asleep only a few hours before the caregivers arrived to get her up and dressed. The experience of unfamiliar caregivers coming in to her personal space, waking her and assisting to her to get out of bed (and quickly due to the pressure of their schedule), made her feel anxious and fearful. Coupled with a lack of analgesia and fatigue, these factors were likely to increase the pain experience. As a result, it could be assumed that Joan’s behaviours of hitting out and shouting could be a combination of her pain as well as fear, demonstrating her unhappiness at her situation.

The Admiral Nurse supported Allan and the caregivers to consider the impact of the morning routine on Joan. Recognising this, the care agency altered the morning call to a later time of 9am, allowing Allan time to administer the analgesia and rouse Joan in a timelier way. The application of the diclofenac gel not only acted by reducing the swelling and pain, but the act of massaging the gel into her knees restored to Joan and Allan a closeness and tenderness which they both enjoyed. This pleasant interaction distracted Joan from her pain, and gave Allan the opportunity to talk quietly and warmly to his wife, which also helped to soothe her pain. When the caregivers arrived an hour later, Joan was calmer, in less discomfort and so more accepting of their assistance. As her behaviour was no longer as challenging, the caregivers were able to support Joan to have a warm bath twice a week, in the evening, which helped her to relax before bedtime and so improved her sleep. Allan described feeling less stressed and upset as he now better understood how pain was impacting on Joan.

CONCLUSION

Recognising, assessing and managing pain in people with dementia can be complex and challenging. Wherever possible, the key is to identify and understand the root cause of behaviours, which may otherwise be attributed to a person’s advancing dementia. It is always worthwhile to first consider the confirmation or exclusion of pain as the first step in an assessment of behaviours that challenge care. It is recommended that a validated behavioral observational assessment measure is used. As BPSD and signs of possible pain in people with dementia are similar in nature, considering pain as a driver should be foremost in the nurse’s mind. This case study also highlights the importance of ensuring appropriate, multimodal approaches to the management of pain to ensure better outcomes for both the person with dementia and their family carers.

When dealing with patients with dementia or their families and carers, it is important that general practice nurses recognise the limitations of their skills and experience, and in cases such as these, referral to an Admiral Nurse can result in better outcomes for the patient and those close to them.

- For further information, see Pain in Dementia from Dementia UK

REFERENCES

1. Sandilyan MB, Dening T. Chapter 1: What is Dementia? In: Harrison Dening, K. Evidence-Based Practice in Dementia for Nurses and Nursing Students. 2019: London: Jessica Kingsley publishers.

2. Sampson EL, Harrison Dening K. (in press) Palliative and End of life Care. In (Eds) Dening T, Thomas A. Oxford Textbook of Old Age Psychiatry. 6th edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

3. McCarthy M, Addington-Hall J, Altmann D. The experience of dying with dementia: a retrospective study. Int J Geriatr Psychiat 1997;12(3):404-09

4. Scherder E, Herr K, Pickering G, et al. Pain in dementia. Pain 2009; 145(3):276-278.

5. Sampson EL, White N, Lord K, et al. Pain, agitation and behavioural problems in people with dementia admitted to general hospital wards: a longitudinal cohort study. Pain 2015;156(4):675-683

6. Feast AR, White N, Lord K, et al. Pain and delirium in people with dementia in the acute general hospital setting. Age Ageing 2018; 47(6): 841-846.

7. Ralph SJ, Espinet AJ. Increased All-Cause Mortality by Antipsychotic Drugs: Updated Review and Meta-Analysis in Dementia and General Mental Health Care. J Alzheimers Dis Rep 2018;2(1):1-26. doi: 10.3233/ADR-170042.

8. Pryor C, Clarke A. Nursing care for people with delirium superimposed on dementia. Nursing Older People 2017;29(3):18-21

9. Tolman S, Harrison Dening K. A relationship-centred approach to managing pain in dementia. Nursing Older People. 2018; 30, 1, 27-32.

10. Jones S, Howard L, Thornicroft, G. Diagnostic overshadowing: worse physical health care for people with mental illness. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2008;118(3):169-171.

Alzheimer’s Research UK. About Dementia - Types of Dementia. 2016. http://www.alzheimersresearchuk.org/about-dementia/types-of-dementia/alzheimers-disease/symptoms/

11. The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) Classification of chronic pain, 1994. https://www.iasp-pain.org/Education/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1698&navItemNumber=576#Pain

12. British Pain Society. Definition of pain. 2014. https://www.britishpainsociety.org/people-with-pain/useful-definitions-and-glossary/#pain

13. Melzack R, Wall P. Pain mechanisms: a new theory. Science 1965; 150, 971-979.

14. McGuire BE, Taheny D, Reynolds B. The Epidemiology of Pain in Dementia. In: Lautenbacher, S, Gibson SJ. (Eds) Pain in Dementia. Philadelphia: IASP Press, 2017; 43-54.

15. Harrison Dening, K. Admiral Nursing: Offering a specialist nursing approach. Dementia Europe. 2010; 1(1):10-11.

16. Herr K, Coyne P, McCaffery M, et al. Pain Assessment in the Patient unable to Self-Report: Position Statement with Clinical Practice Recommendations. Pain Management Nursing 2011;12(4):230-250.

17. Cerejeira J, Legarto L, Mukaetova-Ladinska EB. Behavioural and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia. Frontiers in Neurology 2012;3:73. PMCID: PMC3345875

18. Pace V, Treloer A, Scott S. (Eds) Oxford Handbook: Palliative and End of Life Care in Dementia. 2011; Oxford University Press, Oxford.

19. Fratiglioni L, Qiu C. Chapter 31: Epidemiology of dementia. In: Dening T, Thomas A. (Eds) Oxford Textbook of Old Age Psychiatry, 2nd edition. 2013;Oxford: Oxford University Press

20. Tsai P, Richards K. Using the osteoarthritis specific pain measure in elders with cognitive impairment: a pilot study. J Nursing Management 2006;14(2):90-95

21. Chibnall JT, Tait RC. Pain assessment in cognitively impaired and unimpaired older adults: a comparison of four scales. Pain 2001;92:173-186.

22. Abbey J, Piller N, De Bellis A, et al. The Abbey Pain Scale: a 1-minute numerical indicator for people with end-stage dementia. Int J Palliative Nursing 2004;10:6-13

23. Warden V, Hurley AC, Volicer V. Development and psychometric evaluation of the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD) Scale. J Am Med Directors Assoc 2003;4:9-15.

24. Zwakhalen S, Herr KA, Swafford K. Observational Pain Tools Chapter 10. In: Lautenbacher S, Gibson S J (Eds). Pain in Dementia. Philadelphia: IASP Press, 2017; 133-154.

25. Kristensen RU, Nørgaard A, Jensen-Dahm C, et al. Changes in the prevalence of polypharmacy in people with and without dementia from 2000 to 2014: a nationwide study. J Alzheimers Dis 2019;67(3):949-960.

26. NICE. Management of Osteoarthritis, 2014. https://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/osteoarthritis/management-of-osteoarthritis#content=view-node:nodes-pharmacological-treatments

Related articles

View all Articles