Epilepsy: an introduction for practice nurses

DR GERRY MORROW

DR GERRY MORROW

MB ChB, MRCGP, Dip CBT

Medical Director, Clarity Informatics and Editor, Clinical Knowledge Summaries

Practice Nurse 2021;51(05):23-27

General practice nurses will rarely witness anything more dramatic clinical event that a generalised seizure. Involvement with people who have seizures and their families can be very challenging but also extremely rewarding, as we work to improve their care and their lives

Epilepsy is a serious neurological condition which causes seizures. A seizure is the transient abnormal excessive neuronal activity in the brain.1

Seizures can manifest as disturbances of consciousness, behaviour, cognition, emotion, motor function, or sensation.1,2

Focal seizures – originate in neural networks limited to one hemisphere.3 Focal seizures are divided into those with retained awareness or impaired awareness.4

Generalised seizures – originate in bilaterally distributed neural networks.3 Generalised seizures are divided into motor and non-motor (absence) seizures.4

The International League Against Epilepsy describes epilepsy as a disease of the brain defined by any of the following conditions:1

- At least two unprovoked seizures occurring more than 24 hours apart.

- One unprovoked seizure and a probability of further seizures similar to the general recurrence risk (at least 60%) after two unprovoked seizures, occurring over the next 10 years.

Status epilepticus is a prolonged convulsive seizure lasting for 5 minutes or longer, or recurrent seizures one after the other without recovery between.3

WHAT CAUSES IT?

A cause of epilepsy is only identified in about one third of people with the disorder.2 Causes of epilepsy include:5

- Structural – abnormalities visible on imaging, for example stroke, trauma, or brain malformation.

- Genetic – epilepsy resulting from a known or presumed genetic mutation in which seizures are a core symptom of the disorder.

- Infectious – epilepsy results from a known infection in which seizures are a core symptom of the disorder. Examples include tuberculosis, cerebral malaria, and HIV.

- Metabolic – epilepsy results from a known or presumed metabolic disorder in which seizures are a core symptom of the disorder. Examples include porphyria, amino-acidopathies, or pyridoxine deficiency.

- Immune – epilepsy that results directly from an immune disorder in which seizures are a core symptom of the disorder.

HOW COMMON IS IT?

Epilepsy is one of the most common serious brain conditions, and affects over 70 million people worldwide.3

In the UK, the prevalence of epilepsy is estimated to be 5–10 people per 1000.3 Incidence varies with age, with the highest risk in infants and people over the age of 50 years.6 The incidence of new onset epilepsy in elderly people is increasing.3

People with learning difficulties have higher rates of epilepsy than the general population, making up about 25% of the total of people with epilepsy and 60% of people with treatment-resistant epilepsy.7

WHAT ARE THE RISK FACTORS?

Risk factors vary by age group, but include:2,4,8

- Premature birth

- Complicated febrile seizures

- A genetic condition such as tuberous sclerosis or neurofibromatosis

- Brain development malformations

- A family history of epilepsy or neurological illness

- Head trauma, infections (for example meningitis, encephalitis), or tumours

- Comorbid conditions such as cerebrovascular disease or stroke.

- Dementia and neurodegenerative disorders (people with Alzheimer's disease are up to ten times more likely to develop epilepsy than the general population)

WHAT ARE THE COMPLICATIONS?

Complications include:9

- Sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP), in which a person with epilepsy dies suddenly without an identifiable cause. It is the most common cause of epilepsy-related death in young adults with uncontrolled epilepsy. A significant risk factor is nocturnal seizures.

- Injuries — any seizure involving loss of awareness can cause trauma. Drowning, road accidents, and falls have all been associated with generalised seizures.

- Depression and anxiety disorders are more common in adults and some children with epilepsy, particularly in people with poor seizure control.

- Absence from school or work is more common in people with epilepsy.

WHAT IS THE PROGNOSIS?

It is difficult to give a prognosis for an individual person presenting with suspected epilepsy in primary care, because the prognosis will vary markedly depending on several factors

- Epilepsy syndrome: for example, 80% of people with childhood absence epilepsy will be in remission by adulthood; 90% of people with generalised tonic-clonic seizures, will achieve seizure control.3

- Frequency of seizures — the number of seizures in the six months after first presentation is an important predictive factor for both early and long-term remission of seizures.3

- Response to antiepileptic drug treatment — a strong predictor of favourable long-term outcomes is a positive response to the first antiepileptic drug.2

HOW SHOULD PRACTICE NURSES ASSESS A PERSON PRESENTING WITH A FIRST SEIZURE?

Assessment of a person presenting with a first seizure should include asking about:11

- Any risk factors suggesting a predisposition for epilepsy.

- Clinical features suggesting other causes of seizures, or an alternative diagnosis to epilepsy.

- What happened before, during and after the attack (from the patient and an eyewitness).

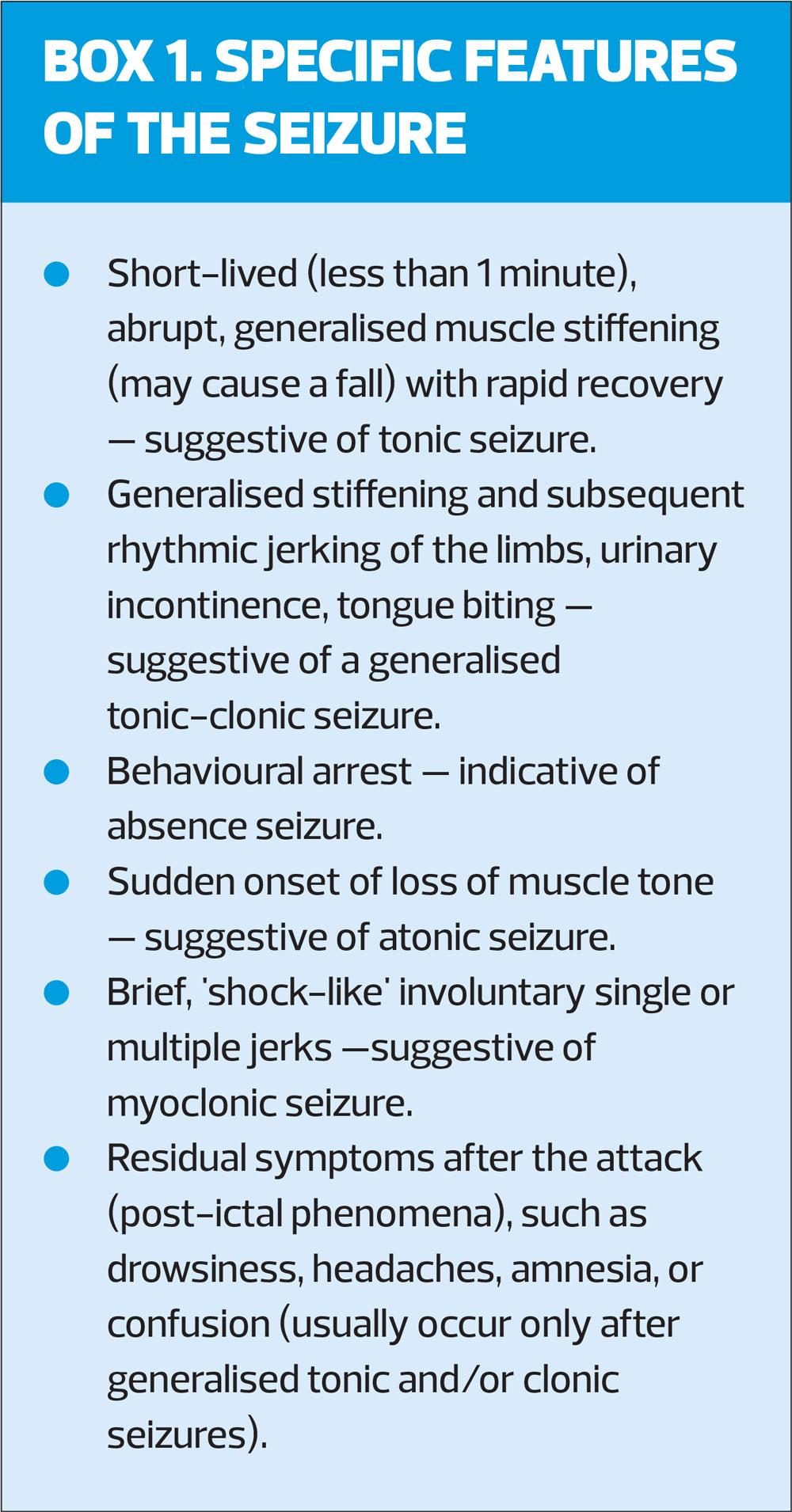

This should include any subjective symptoms at the start of the seizure (aura) – suggestive of focal epilepsy, and any potential triggers, for example sleep deprivation, stress, light sensitivity, or alcohol use. GPNs should also enquire about specific features of the seizure (Box 1).

Practice nurses who look after people with epilepsy should consider an examination including:

- Heart, neurology, and an assessment of mental state.

- Examination of the mouth to identify any tongue bites.

- Identification of any injuries sustained during the seizure.

Consider arranging baseline tests for adults with suspected epilepsy, including full blood count, urea and electrolytes, liver function tests, glucose, and calcium and a 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG).8

WHAT ELSE MIGHT IT BE?

Conditions which may present with similar features to epilepsy include:3,8

- Vasovagal syncope

- Cardiac arrhythmias

- Panic attacks

- Non-epilepsy disorders or pseudo-seizures

- Transient ischaemic attack

- Migraine

- Medication, alcohol, or drug intoxication

- Sleep disorders

- Movement disorders

- Hypoglycaemia

- Delirium or dementia

In children, differential diagnoses include:

- Febrile convulsions

- Breath-holding attacks

- Night terrors

- Stereotyped/ritualistic behaviour — especially in those with a learning disability

MANAGEMENT

Practice nurses should urgently refer all people suspected of having a first epileptic seizure to a specialist, to confirm the diagnosis. The referral letter should include a detailed description of the seizure from a first-hand witness, if possible.3

Advise the family or carers of the person with suspected epilepsy:

- How to recognise and manage a seizure, including factsheet which contains advice on first aid and when to call an ambulance – available from Epilepsy Action www.epilepsy.org.uk.10

- To record any further episodes of possible seizures, for example on a mobile phone and/or seizure diary.

- To stop driving while waiting to see the specialist and to avoid potentially dangerous work or leisure activities.

- About lifestyle factors that can lower the seizure threshold, for example sleep deprivation and the use of alcohol and drugs.

- To return for further advice if further episodes occur while they are waiting to see the specialist.

HOW SHOULD GPNs MANAGE A PERSON HAVING AN EPILEPTIC SEIZURE?

For people having a seizure, note the time, and if it lasts less than 5 minutes:3,6,10,11

- Look for an epilepsy identity card or jewellery

- Protect them from injury by:

- Cushioning their head, for example with a pillow

- Removing glasses if they are wearing them

- Removing harmful objects from nearby, or if this is not possible, moving the person away from immediate danger

- Do not restrain them or put anything in their mouth

- When the seizure stops, check their airway, and place them in the recovery position

- Observe them until they have recovered

- Examine for, and manage, any injuries.

Call for an ambulance if it is their first seizure; a seizure reoccurs shortly after the first one; the person is injured or having trouble breathing after the seizure, or is difficult to wake up.

For people having a tonic-clonic seizure lasting more than 5 minutes, or who have more than three seizures in an hour, practice nurses should also start treatment with buccal midazolam as first-line treatment in the community, or rectal diazepam if preferred, or if buccal midazolam is not available.

HOW SHOULD GPNs MONITOR A PERSON WITH CONFIRMED EPILEPSY?

Practice nurses should undertake a routine review of all people with epilepsy in primary care at least once a year. During this review you should:

- Ensure the person and their carers are aware of who to contact if there are problems relating to their epilepsy, such as a named epilepsy specialist nurse.

- Assess seizure control by asking about seizure frequency and severity, and any changes since the person was last reviewed.

- For people who have more than one type of seizure, identify how frequently they have each seizure type.

- Ask about how epilepsy is affecting the person's daily functioning and quality of life, and provide advice on sources of information and support for the person, their family and/or carers.

- Assess for any symptoms or signs of anxiety, depression, and memory or cognitive deficit.

- Ask about the impact of epilepsy on work, educational, and leisure activities; any associated difficulties or risks, and how they manage them. Check there is appropriate supervision during water activities, such as swimming or bathing, to reduce the risk of accidental drowning.3,8,12

- If the person is driving, or wants to drive, ensure they are entitled to do so and have contacted the DVLA.13

- Ensure that any carer for a person with epilepsy is aware of how to recognise and manage a seizure, including when and how to give buccal midazolam or rectal diazepam for prolonged or recurrent seizures, if appropriate.

- Ask about any adverse effects and compliance with antiepileptic drug treatment. Ensure the person (or their family or carers) understands the importance of compliance to reduce the risk of seizures and/or SUDEP.

In addition you should consider measuring blood levels of antiepileptic drugs if drug toxicity or non-compliance is suspected. Children with epilepsy will usually have blood tests performed in secondary care.

Nurses should also take this opportunity to assess the person’s risk of osteoporosis, which may be higher with some anti-epilepsy medication, and offer lifestyle, dietary advice, and calcium and vitamin D supplementation, if appropriate.14

WHEN TO SEEK SPECIALIST ADVICE FOR A PERSON WITH CONFIRMED EPILEPSY

Practice nurses involved with people with epilepsy should seek specialist advice if the person has:3,8,11

- Poor seizure control, or their drug treatment is poorly tolerated

- Previously had a tonic-clonic seizure lasting more than 5 minutes, or more than three seizures in an hour, and they have not previously been prescribed buccal midazolam or rectal diazepam to treat future episodes.

- Possible cognitive impairment secondary to epilepsy and/or its drug treatment.

- Been seizure-free for the last 2 years and would like to consider tapering or withdrawing their drug treatment.

WHAT CONTRACEPTIVE ADVICE SHOULD GPNs OFFER A WOMAN WITH EPILEPSY?

Contraceptive advice should be given to women and girls with epilepsy before they become sexually active. Advise women receiving enzyme-inducing antiepileptic drugs that:8,15

- Enzyme-inducing drugs may reduce the effectiveness of oral contraceptives (combined hormonal contraception, progestogen-only pills), transdermal patches, the vaginal ring, and progestogen-only implants, and an alternative contraceptive method is recommended.

- Methods unaffected by enzyme-inducing drugs include medroxyprogesterone acetate injections or an intrauterine method.

- There are potential interactions with enzyme-inducing drugs and oral methods of emergency contraception, therefore, a copper intrauterine device is the preferred option.

Practice nurses should specifically advise women with epilepsy who are taking lamotrigine that progestogen-only contraceptives can be used without restriction, but that the woman should report any symptoms or signs of lamotrigine toxicity.

HOW SHOULD GPNs MANAGE A WOMAN WITH EPILEPSY WHO IS PLANNING A PREGNANCY OR IS PREGNANT?

Ensure women with epilepsy receive pre-pregnancy counselling at the time of diagnosis and regularly thereafter. Specifically discuss the risk of continued use of sodium valproate, which should not be used in any woman or girl able to have children unless there is a pregnancy prevention programme in place, because of the high risk of birth defects and developmental disorders associated with this drug. (Valproate for the treatment of epilepsy is banned in pregnancy unless no other effective treatment is available.)15

If a woman with epilepsy is planning a pregnancy, you should advise that:3,16

- Most women with epilepsy will have a normal pregnancy and delivery and a normal healthy baby

- Women who are seizure-free before conception are likely to remain so during pregnancy.

- Women with epilepsy who are not taking antiepileptic drugs probably do not have an increased risk of fetal malformations compared with women without epilepsy.

- The risk of congenital abnormalities in the baby depends on the type, number and dose of antiepileptic drugs taken, but antiepileptic drugs do not increase the risk of spontaneous miscarriage and stillbirth.

- Inadequate seizure control may put the fetus at more risk of harm than the use of antiepileptic drugs in pregnancy. Advise women of the risks of uncontrolled seizures for themselves and their fetus.

Practice nurses should refer the woman to an epilepsy specialist for pre-conceptual counselling, especially if she is taking antiepileptic drugs. Advise her to:3,8,11

- Continue using effective contraception until she has been assessed by a specialist.

- Continue her antiepileptic drugs and make an urgent appointment to see a healthcare professional if she becomes pregnant unexpectedly.

- Take high-dose folic acid 5 mg daily. This should be continued throughout the first trimester.

CONCLUSION

Epilepsy is a substantial problem for many people, some of whom have significant additional multi-morbidities. The challenge for practice nurses managing people with epilepsy is that it involves many facets of their lives, from medication, safety, driving, pregnancy and even life expectancy.

Understanding these wide-ranging issues and bringing our professionalism and compassion to each consultation enables us to improve the care and the lives of people with epilepsy and their families.

REFERENCES

1. Fisher RS, Cross JH, French JA. (2017) Operational classification of seizure types by the International League Against Epilepsy: Position Paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia 2017;58(4):522-530.

2. Krishnamurthy KB. Epilepsy. Annals Int Med 2016;164(3):ITC17-32

3. NICE CG137. Epilepsies: diagnosis and management; 2012 (Updated 2021) https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg137

4. Thijs RD, Surges R, O'Brien TJ. Epilepsy in adults. Lancet 2019;393(10172):689-701.

5. Scheffer IE, Berkovic S, Capovilla G. ILAE classification of the epilepsies: Position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia 2017;58(4):512-521.

6. Legg KT, Newton M. Counselling adults who experience a first seizure. Seizure 2017;49:64-68.

7. Royal College of Psychiatrics. Prescribing anti-epileptic drugs for people with epilepsy and intellectual disability. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/improving-care/campaigning-for-better-mental-health-policy/college-reports/2017-college-reports/prescribing-anti-epileptic-drugs-for-people-with-epilepsy-and-intellectual-disability-cr206-oct-2017

8. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. SIGN 143. Diagnosis and management of epilepsy in adults; 2018 https://www.sign.ac.uk/media/1079/sign143_2018.pdf

9. Fiest KM, Sauro KM, Wiebe S. Prevalence and incidence of epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis of international studies. Neurology 2017;88(3):296-303.

10. Epilepsy Action. What to do when someone has a seizure; 2016 https://www.epilepsy.org.uk/info/firstaid/what-to-do

11. National Clinical Guideline Centre. The epilepsies. The diagnosis and management of the epilepsies in adults and children in primary and secondary care; 2012. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25340221/

12. NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Epilepsy; 2021. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/epilepsy/management/

13. DVLA. Assessing fitness to drive - a guide for medical professionals; 2019. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/assessing-fitness-to-drive-a-guide-for-medical-professionals

14. MHRA. Antiepileptics: adverse effects on the bone. Drug Safety Update 2009;2(9):2.

15. MHRA. Information about the risks of taking valproate medicines during pregnancy. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/valproate-use-by-women-and-girls

16. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Epilepsy in Pregnancy Guideline No.68; 2016. https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-research-services/guidelines/gtg68/