Optimising the management of gout: Guideline in a nutshell

MANDY GALLOWAY

MANDY GALLOWAY

Editor

Practice Nurse 2022;52(6):14-16

Sudden severe pain in joints, most commonly the big toes, heat and swelling – it can only be gout. But only one in three patients is receiving appropriate treatment to manage their condition effectively

Gout is the most common inflammatory arthritis. Between two and three people in every 100 people in the UK have gout, a type of arthritis caused by monosodium urate (MSU) crystals forming inside and around joints. Although any joint can be affected, gout is most common in distal joints such as the big toes, knees, ankles and fingers.1

Gout has a range of different clinical manifestations: in addition to recurrent, acute attacks or flares, subcutaneous tophi – white growths that develop around the affected joints, often visible under the skin – and chronic painful arthritis, it also has an impact on morbidity and premature mortality.2

Gout usually occurs in men over 30, and women after menopause. It is more common in men, affecting four in 100, compared with one in 100 women. Long term complications of gout include joint damage and renal stones. The prevalence of chronic kidney disease (CKD) is also higher in people with gout.1

Gout is usually managed in primary care without input from rheumatology specialists. A flare is usually treated with a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), colchicine or steroids. However, most people go on to have further flares.1

These can be prevented by a combination of lifestyle modification, including losing weight and changing diet to avoid purine-rich foods, and drugs to reduce urate levels such as allopurinol or febuxostat.1

Effective urate-lowering treatment (ULT) that maintains uric acid below the saturation point for deposition of crystals prevents further crystal formation and dissolve existing crystals, making gout the only chronic arthritis that can be cured.2

However, only a third of patients who consult in general practice are treated with ULT,1,2 and only a third of these are treated effectively – i.e., lowering their serum uric acid (sUA) level to the biochemical target.1 Furthermore, the agents used to manage gout are often contraindicated in patients with CKD, necessitating dose adjustments or alternative treatments. And drugs commonly prescribed for patients with cardiovascular conditions, including those with CKD, such as thiazides and loop diuretics increase sUA levels, compounding the problem.

These factors have prompted NICE to issue a new guideline, which aims to improve the diagnosis and management of gout.3

DIAGNOSIS

Despite being the most common inflammatory arthritis in the UK, gout is not always well-recognised by healthcare professionals, but effective management of gout rests, at least in part, on an accurate diagnosis. Gout usually presents with rapid onset, often overnight, of severe pain together with redness and swelling in one or both first metatarsophalangeal joints with or without tophi (which may indicate that gout has been present but untreated for some considerable time). Gout should also be considered in people who present with these symptoms in other joints, for example, midfoot, ankle, knee, hand, wrist or elbow.

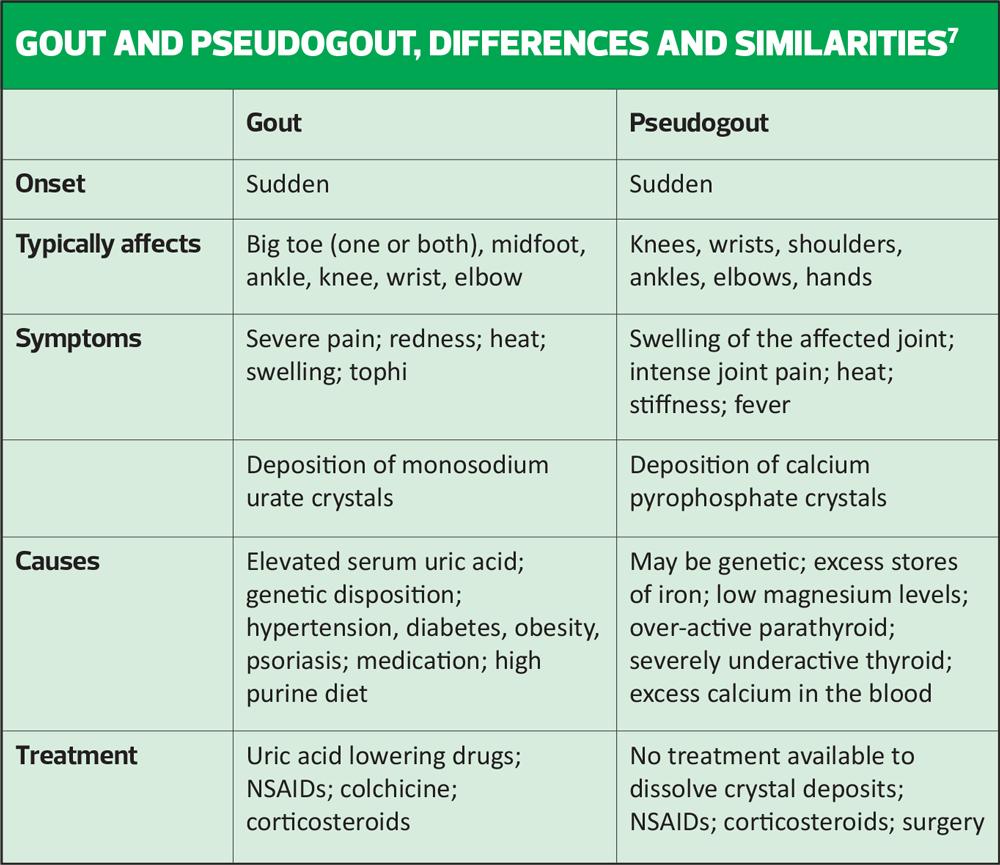

However, if someone presents with a painful, red, swollen joint, it is important to consider other diagnoses, such as inflammatory arthritis, calcium pyrophosphate deposition (pseudogout - see Table overleaf), or septic arthritis.3 Septic arthritis is caused by infection in the joint, and while symptoms may resemble those of other arthropathies, it is usually accompanied by fever. It is a medical emergency and requires immediate specialist referral to avoid permanent joint damage.

Measure the person’s sUA level to confirm the diagnosis (≥360μmol/l). If the level is below 360mmol/l during a flare and gout is strongly suspected, repeat the test 2 weeks after the flare has settled.1

Other diagnostic tests include joint aspiration and microscopy of synovial fluid, X-ray, ultrasound or dual-energy CT.

INFORMATION TO PROVIDE TO PATIENTS

Offer tailored information to patients at the time of their diagnosis and at subsequent follow-up appointments, to include:

- The symptoms and signs of gout

- Causes

- That the disease progresses without treatment because continuing high levels of urate in the blood lead to the formation of new urate crystals

- Any risk factors that they have, and comorbidities such as CKD or hypertension

- That gout is a lifelong condition that benefits from long-term treatment to eliminate urate crystals, prevent flares, shrink tophi and prevent joint damage

- Where to find further information and local support groups

TREATMENT FOR GOUT FLARES

NICE recommends offering patients experiencing a flare treatment with either an NSAID (with a PPI), colchicine or a short course of oral corticosteroids (off label use). There is no difference in effectiveness between these options for pain and joint tenderness or swelling, although generally an NSAID or colchicine would be offered before oral steroids. Where these treatments are contraindicated, not tolerated or ineffective, intra-articular and intramuscular corticosteroids can be considered.

Although interleukin (IL-1) inhibitors have been shown to improve pain and quality of life, and are recommended by the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR), they are not recommended by NICE because of the cost, and NICE recommends that the patient should be referred to rheumatology before they are prescribed.

A non-pharmacological approach that has been shown to be helpful is the application of ice packs, which should be used alongside medication to ease pain and inflammation.

Once the flare has settled, offer a follow up appointment to measure the sUA level, provide information about self-management and reducing the risk of future flares, assess lifestyle and comorbities, review medication and discuss the risks and benefits of long-term ULT.

NICE says there is insufficient evidence to recommend specific diets to prevent flares or lower sUA levels. Instead, people with gout should be advised to follow a healthy balanced diet. However, excess body weight or obesity, or excessive alcohol consumption, may exacerbate gout flares and symptoms.

LONG TERM MANAGEMENT

Treatment with ULT is usually lifelong. It should be continued even when target sUA levels have been achieved. ULT should be offered to all people with gout who have:

- Multiple or troublesome flares

- CKD stages 3–5

- Diuretic therapy

- Tophi

- Chronic gouty arthritis

ULT should be started at least 2–4 weeks after a gout flare has settled. The treatment strategy should be to treat-to-target, i.e. starting with a low dose of ULT (e.g. allopurinol 50–100mg daily) and using monthly sUA levels to guide dose increases, provided they are tolerated, until the target sUA level is reached. For most people the target should be below 360μmol/l, but consider a lower target (below 300μmol/l) for people who have tophi or chronic gouty arthritis, and continue to have frequent flares despite having a sUA level below 360μmol/l.

Gout is often undertreated and this may be because of uncertainty about optimum target sUA levels: The British Society for Rheumatology (BSR) and EULAR recommend a target of 300 μmol/l,4,5 but NICE considers this would increase the costs of treating gout unnecessarily.

There are two main urate lowering treatments available, allopurinol and febuxostat. Both have been shown to reduce serum urate levels to target, when compared with placebo. The evidence shows that the target sUA level is achieved more frequently with febuxostat than with allopurinol, and it is easier to titrate than allopurinol (there are only two doses available, and it is taken once daily) but it also causes more flares.

Either drug is recommended first line, although allopurinol is preferred for people with gout who have major cardiovascular disease. If the target sUA level is not achieved, or first line treatment is not tolerated, consider switching to the alternative drug.1

In patients with renal impairment, smaller increments (50mg) of allopurinol should be used during titration and the maximum dose should be lower: the manufacturers recommend a maximum dose of 100mg a day, and in severe renal impairment, dosing on alternate days.6 If this is insufficient to reach target, switch to febuxostat at a starting dose of 80 mg, and increase after 4 weeks (if necessary) to 120mg daily.

NICE points out that allopurinol doses up to 300mg are often too low to achieve target sUA, and that many people with gout would require a higher dose to manage their condition.1 The maximum dose for allopurinol is 900mg daily, depending on the individual’s renal function.4

Monitoring

Annual monitoring of sUA in people who are continuing ULT after reaching their target is recommended for several reasons:

- sUA levels can increase with age, changes in lifestyle, comorbidities or medication

- People may stop ULT once they feel better, but continuation is important as sUA can increase rapidly once ULT is stopped

- Without monitoring, adherence may be poor, leading to worse outcomes.1

The frequency of monitoring is highly variable, as patients often only make an appointment at which their sUA level is measured in response to flares. The NICE guideline development committee agreed that this is not sufficient, as the goal of monitoring is to prevent flares rather than to manage them.1

PREVENTING FLARES WHEN STARTING ULT

Paradoxically, initiation of urate lowering therapy can trigger a gout flare, thought to be the result of remodelling of crystal deposits as they dissolve. The more rapid the reduction in sUA, the more likely a flare will occur.5

To counter this effect, offer colchicine to prevent flares while the sUA level is being reached. If colchicine is contraindicated, not tolerated or ineffective, consider a low-dose NSAID or low-dose oral corticosteroid. As of June 2022, this was off label use. It is therefore important to make a clear record of the medicine prescribed, and your reason for prescribing it.1

REFERRAL

Consider referring the person with gout to a rheumatology specialist if:

- The diagnosis is uncertain

- Treatment is contraindicated, not tolerated or ineffective

- The patient has CKD stages 3b to 5 (GFR categories G3b to G5)

- They have had an organ transplant.

CONCLUSION

Missing a diagnosis of gout would mean treatment is delayed, with the concomitant risk of permanent joint damage, disability and reduced quality of life. Although gout is described as the only curable arthropathy, in reality without effective, ongoing urate lowering therapy, it can cause acutely painful flares at any time. Treating-to-target can reduce the risk of flares, which is something that anyone who has experienced one would wish ardently to avoid.

REFERENCES

1. NICE NG219. Gout: diagnosis and management. Guideline scope; 2020. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng219/documents/final-scope-2

2. Kuo C-F, Grainge MJ, Mallen C, et al. Rising burden of gout in the UK but continuing suboptimal management: a nationwide population study. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:661-667

3. NICE NG219. Gout: diagnosis and management; 9 June 2022. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng219

4. Hui M, Carr A, Cameron S, et al. The British Society for Rheumatology guideline for the management of gout. Rheumatology 2017;56(7):1056-1059

5. Fen X, Li Y, Gao W. Prophylaxis of gout flares after the initiation of urate-lowering therapy: a retrospective research. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015;8(11):21460-465

6. Sigma Pharmaceuticals. Allopurinol 100mg tablets Summary of Product Characteristics. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/9467/smpc#gref

7. Arthritis Foundation. Calcium pyrophosphate deposition. https://www.arthritis.org/diseases/calcium-pyrophosphate-deposition