Non-adherence to therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: overcoming the problems

Tracy French

Tracy French

RGN, Dip HE, MSc, NMP

Rheumatology Clinical Nurse Specialist

University Hospitals Bristol & Weston

NHS Foundation Trust

Practice Nurse 2022;52(3):24-29

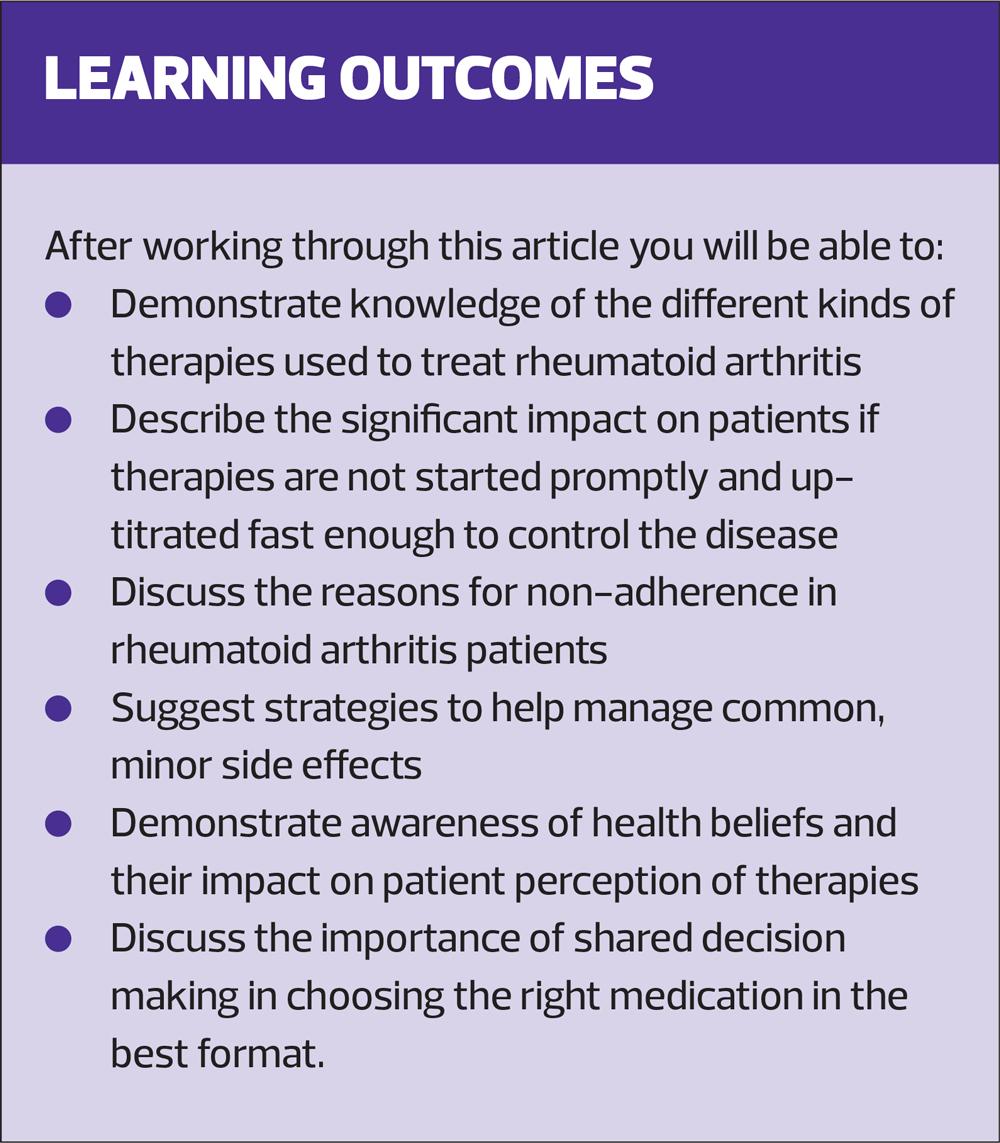

Early treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) can prevent disease progression and help patients achieve sustained remission, but poor adherence is common. Educating patients about their treatments is vital to improve adherence and maximise their quality of life

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is an autoimmune condition causing joint pain and inflammation. It is characterised by exacerbations (flares) and periods of remission, but left untreated it can result in irreversible joint damage and deformity. It is more common in women than men, but affects approximately 400,000 of the UK population.1

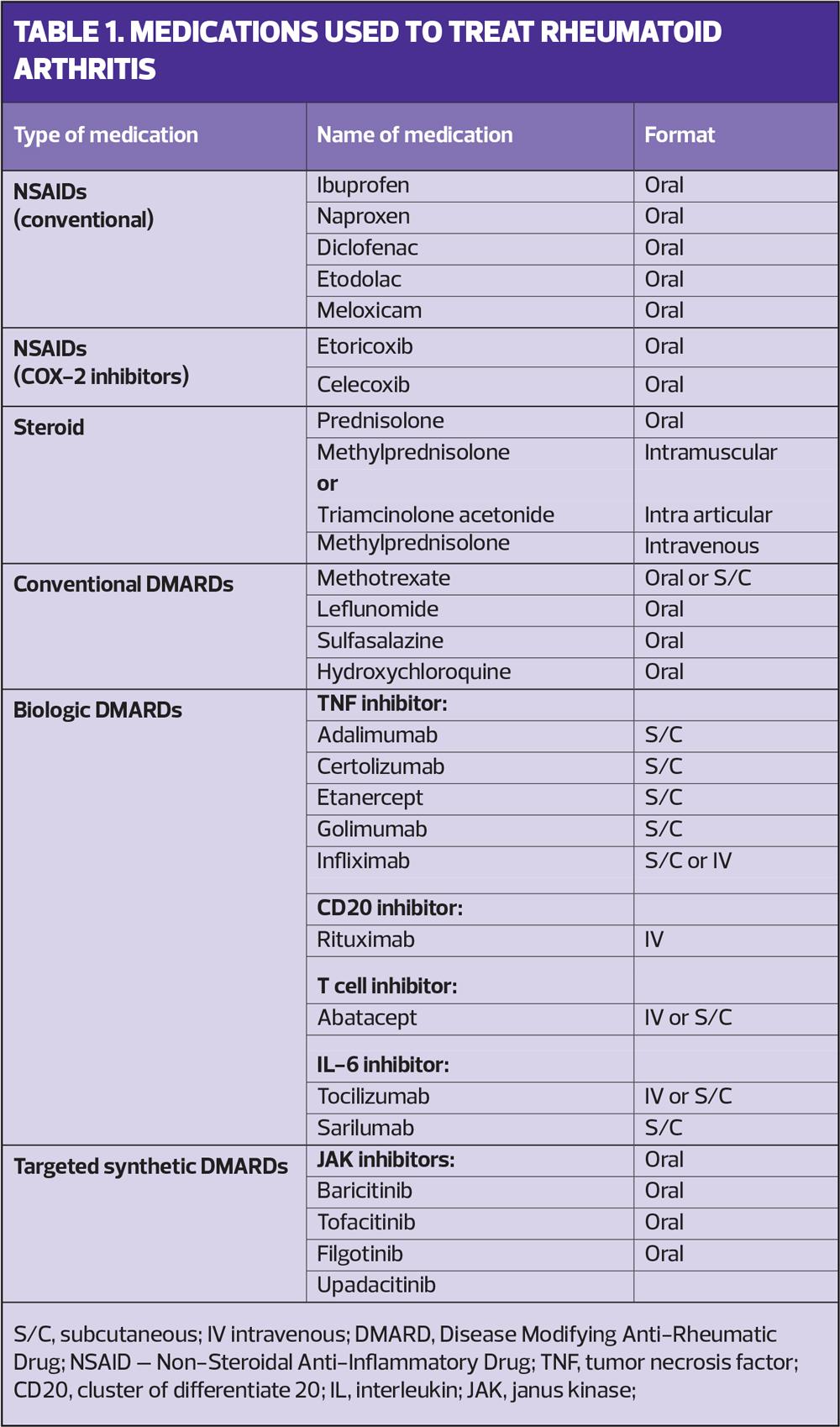

There are a variety of medications used to manage RA (Table 1). Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) slow the disease process and reduce the risk of joint damage. They are first line therapies and are used alone or in combination depending on the severity of the disease. Severity is assessed on clinical examination and by using a validated assessment tool, the Disease Activity Score (DAS).2 It is vital DMARDs are started as early as possible after diagnosis and up-titrated quickly (if tolerated) to the appropriate dose to effectively manage the inflammation. The aim is for disease remission, to reduce the likelihood of joint damage and subsequent joint deformity.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors reduce inflammation and give symptomatic relief. They should be used while waiting for DMARDs to become effective and during flares. Their long-term, daily use, however, should be discouraged due to the well-documented risk of adverse effects.

Steroids, in varying forms, are used to manage flares; this can be a short course of oral prednisolone, an intramuscular injection of steroid, intra articular injections or intravenous methylprednisolone infusions.

NICE has approved the use of biologic therapies (Table 1) for patients with severe disease,1 and, more recently, for those with moderate disease,3 as assessed by a DAS. However, part of the eligibility criteria is for patients to have tried at least two conventional DMARDs, one of which must be methotrexate, at a dose of at least 15mg for a minimum of 3 months, unless contraindicated or not tolerated.1

DMARDs are therefore the cornerstone of treating early RA but, in the author’s experience, are the therapies where most issues with adherence occur. For patients, treatment of early RA is the most important, pivotal point in their disease management and irrevocably determines how the disease will impact their quality of life.

A new survey exploring RA patients’ treatment experience, carried out by the National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society (NRAS), found that over 70% of patients stopped taking their oral methotrexate, increasing the risk of worsening symptoms and remission relapse.4

REASONS FOR NON-ADHERENCE

There are a variety of reasons for non-adherence with DMARDs. The following three case studies reflect the most common.

Side effects and lack of understanding regarding onset of efficacy

John is 54. He is newly diagnosed with mild RA and has been taking sulfasalazine for 3 weeks. He has been troubled by wind and bloating which he finds embarrassing. His joints are worse than when he saw the rheumatologist and fatigue is affecting his work as a taxi driver. He thinks the tiredness came on since he has been taking the sulfasalazine so he has decided to stop it.

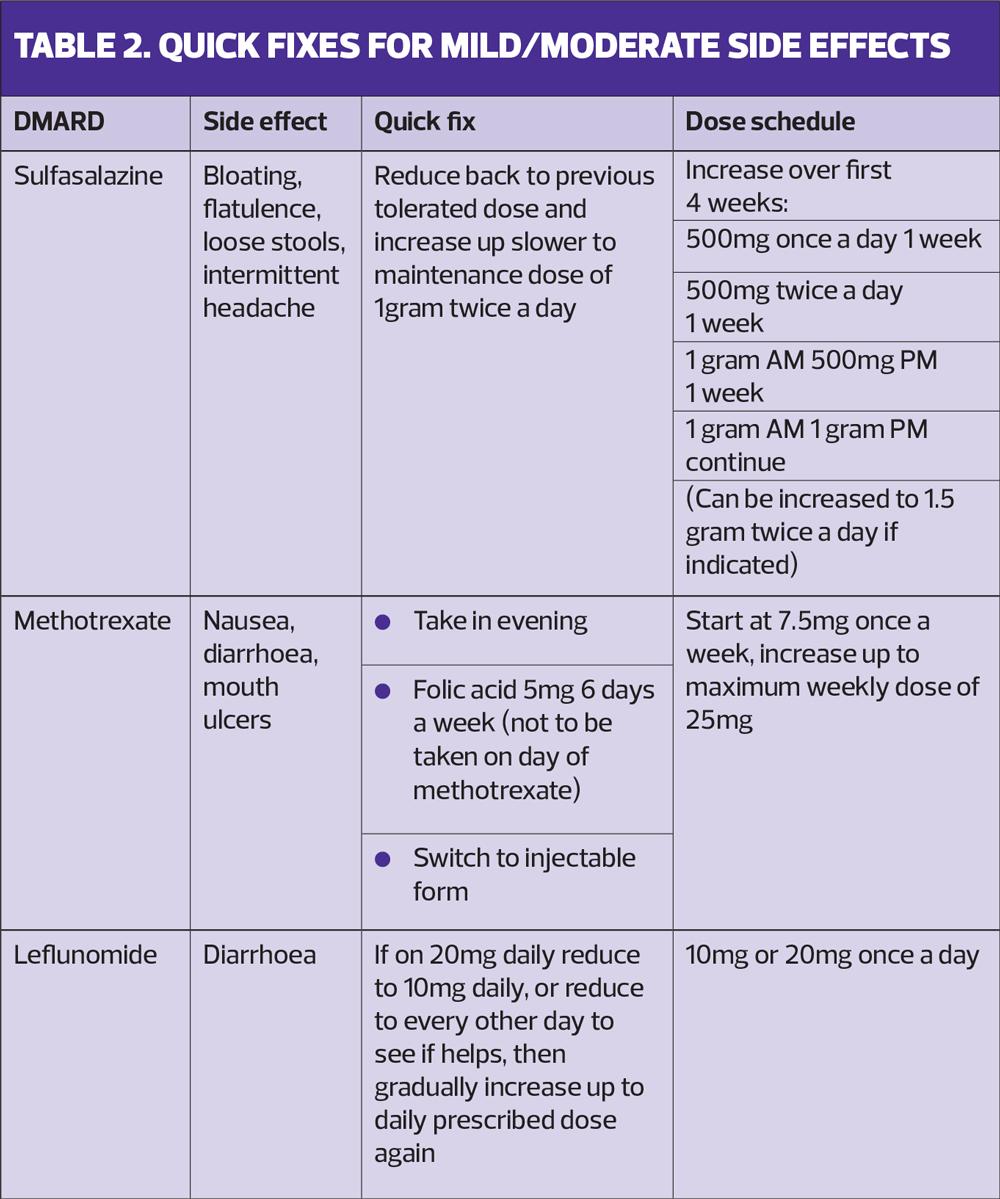

Sulfasalazine is up-titrated over the initial 4 weeks to a maintenance dose. It can cause wind and bloating, but this will often settle by returning to a lower dose (which was tolerated by John) and up-titrating more slowly (Table 2).

Sulfasalazine takes 8-12 weeks to be fully effective. If this has not been explained to John, he will feel resentful that he is having side effects but no benefits. It is also important that he understands that the medication will not make his joint pain worse. His worsening joint pain is more likely to be due to his arthritis progressing as the medication isn’t yet controlling it fully.

Sulfasalazine can occasionally cause fatigue. It is, however, more likely that John’s fatigue is caused by his condition so, again, it is important that he understands that fatigue is part of his condition and that this may improve once his treatment brings his RA under control.

This case study reflects the importance of educating patients about:

- How long medication will take to be effective

- How to manage common and minor side effects, and

- How to differentiate between effects likely to be related to the medication and those related to the disease itself.

This education should occur in secondary care but, as information may not be retained, it should also be reinforced in primary care.

Health beliefs and perception of DMARD therapies as toxic

Anadia is 65 years old and was diagnosed with moderately active RA 12 months ago. She attends clinic with a significant flare. She has lots of swollen joints, and is in considerable pain. She has also lost weight and is anaemic due to on-going inflammation. She doesn’t speak any English so an interpreter is used.

When first diagnosed, Anadia was not given oral glucocorticoids as she has poorly controlled diabetes. It was therefore recommended that she start methotrexate tablets and she was given an intramuscular methylprednisolone injection. At every subsequent visit to Rheumatology she requested another steroid injection as she found them very effective and gave her quick relief. These had been given, based on the expectation she would continue taking the methotrexate. Looking back through her notes, however, it was hard to establish if she took methotrexate consistently, if at all.

An additional visit with the nurse specialist in secondary care was therefore arranged in order to allow time to discuss Anadia’s concerns about taking methotrexate. This revealed that she perceived the medication as ‘poison’ because of the need for blood tests and the possibility of hair loss as a side effect. However, she did take if for the first few weeks but experienced nausea for 24 hours after each dose. This meant she didn’t eat or drink anything and spent the day in bed.

Anadia’s reliance on a steroid as a fast way to manage her arthritis is seen commonly in practice. She experienced fast relief of her symptoms and didn’t experience any immediate side effects. However, education is needed so that she understands that reliance on steroids has health implications, particularly related to her diabetic control.

Some simple solutions to try to encourage regular dosing of methotrexate would be to suggest that she takes the methotrexate tablets at night. This will reduce the day-time nausea. Another ‘quick fix’ can be to ensure she is taking folic acid 5mg every day of the week except the day she takes the methotrexate. This can help reduce side effects such as nausea. Finally, if these are not effective then a switch to methotrexate injections should mean the nausea no longer occurs (Table 2).

Impact of DMARDs on social and work life

Josh is 28 and was diagnosed with RA 6 months ago. He works in the TV industry as a cameraman and his work involves travel and lots of socialising. He is reviewed in clinic but, despite being on 20mg methotrexate weekly, his arthritis continues to flare and he has needed two intra-articular injections into his wrists.

During the consultation it becomes evident he has not been taking the methotrexate every week as prescribed. He has been missing doses when he is socialising with work or spending weekends at festivals, where he likes to drink alcohol and take recreational drugs. He has also had issues taking time out of work to have regular blood tests and this has meant he has also missed doses.

It is important for Josh to understand that he needs to take methotrexate regularly for it to be effective, and to keep taking it even if his arthritis is not flaring. It is recommended with both methotrexate and leflunomide that alcohol intake is no more than 14 units a week, and recreational drug use would not be advisable. Therefore, it is important that Josh is given the opportunity to have a frank and open discussion about his lifestyle choices and whether or not he is willing to compromise on these. It is also important to clarify if there is any flexibility in the timing of his blood monitoring appointments, in order to minimise the impact this has on his work. Without regular tests it would not be safe for him to continue taking methotrexate.

These three scenarios are all different, but have similar themes. They reflect the part health beliefs play in patients’ perceptions of medications, and the importance of shared decision making in managing patients on DMARDs.

HEALTH BELIEFS AND SIDE EFFECTS

All three of the above case scenarios illustrate that patients will weigh up the need for them to take the DMARD versus their concerns regarding potential adverse effects. There is also the alternative option of steroid (in various forms) and this is often (often mistakenly) perceived as a much quicker solution with fewer adverse effects.

A cross sectional survey of over 300 RA patients examined their beliefs about their medications, what factors related to these beliefs and how these affected adherence.5 Three-quarters (75%) of patients had positive beliefs about the necessity of their medication, but 50% had strong concerns about potential adverse effects in the long-term. The greater number of DMARDs patients were taking, the greater their concerns about medications, even after adjusting for variables such as pain, fatigue and disability. Unfortunately, the patients with the most active disease are those who will need to take two or three DMARDs, and if they are non-adherent they will have the most to lose in terms of damage to their joints and long term disability. The least adherent patients in the study were the ones with the greater medication concerns, but the beliefs about the necessity for the medications were the same in all patients. This would suggest that reassuring patients about the long-term safety of medications is more important than about how effective they will be.

A further longitudinal study of 100 RA patients examined the relationship between medication beliefs and side effects, at baseline and 6 months later.6 The majority of the reported side effects in this study were non-serious and the reported non-specific symptoms were not clearly related to the pharmacologic action of the drug in question. Yet these symptoms are still frightening for patients and often result in non-adherence. The authors of this study refer to the nocebo phenomenon, where patients report side effects to placebo. They found that patient’s beliefs about medications influenced their experience of side effects, even after adjusting for variables such as disease activity, types of medications and levels of prior experience of side effects. In effect, patients with greater concerns about their medications experience more side effects, and patients starting new medications are more likely to have side effects if they have negative perceptions about medicines at baseline.

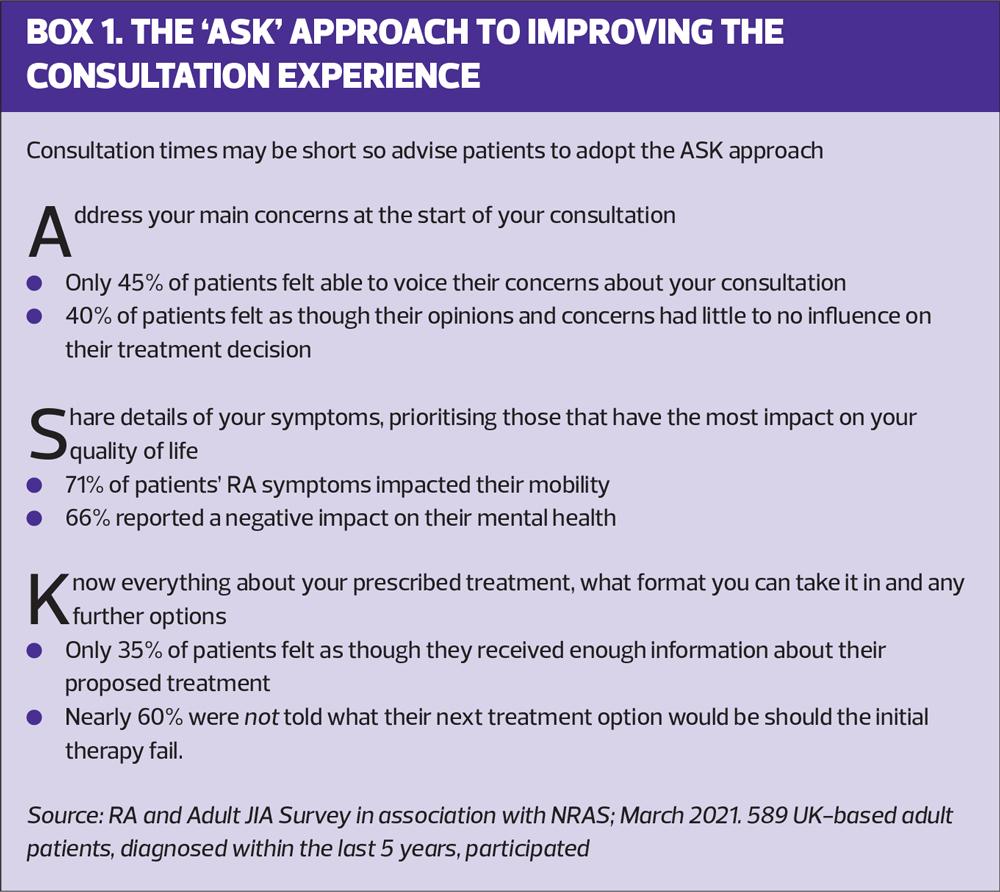

The NRAS patient experience survey found that the primary impact upon treatment adherence was unpleasant gastrointestinal side effects. This contributed to over 45% of patients experiencing an overall negative impact on their quality of life and caused many to stop their treatment altogether. Further findings also suggest that poor adherence to methotrexate is linked to the patients’ lack of understanding and involvement in their treatment choice.4

It is important to note that when referring here to side effects these are presumed to be minor and manageable. If there are more serious side effects, such as blood abnormalities, hypersensitivity pneumonitis or skin rashes indicating an allergic reaction, the patient should be referred urgently to secondary care (usually via a nurse specialist advice line).

SHARED DECISION MAKING AND PATIENT EMPOWERMENT

The Royal Pharmaceutical Society suggests four guiding principles of medicines optimisation. The most relevant to adherence is understanding the patient’s experience. To obtain the best possible outcome the RPS suggests that it is vital to have on-going and open dialogues with patients about their choices and experience of using medicines.7 In each of the above case scenarios having the opportunity to explore the beliefs and preferences of John, Anadia and Josh, along with a safe space for them to be open about how the medication impacts on their daily lives, can result in true, shared decision making which would, hopefully, result in better adherence.

The ‘ASK – Address, Share, Know’ approach (Box 1), together with shared decision-making tools, can help structure the consultation and help patients obtain the information they need within the time allocated. It helps to empower patients to address their most pressing concerns at the start of the consultation. They should be encouraged to share their most intolerable symptoms and we need to give them as much information as they need about their prescribed treatment, and any other options if it fails to work for them. This ensures that they are involved in their treatment decisions and this leads to better adherence and treatment outcomes.

The opportunity for sharing decision making should not be limited to secondary care. Primary care practitioners, including primary care nurses, are in a unique position to have these open conversations with patients as they are often seeing them on a more frequent basis, for example when attending for blood monitoring. If patients are having problems tolerating their medications it is important that they know there are ways to manage this, or therapy alternatives. There is also the opportunity at an annual review to monitor repeat prescription requests to assess if medication is being taken appropriately.

ACCESSING SUPPORT

Nurse advice lines are the most common way rheumatology patients access their team for information and support. NICE recommends patients should receive a call back within 24 hours.8 A large number of these calls will be about adverse effects from DMARDs. This is often the platform where shared decision making takes place, as in the following case study.

Jane, a patient in her 20’s, calls because she is having significant nausea and loose bowels for 48 hours after taking oral methotrexate. She has tried taking it in the evening on a Friday so she is unwell over the weekend but can still perform at work. This means she is not able to socialise with friends at the weekend and is too tired to do this on weeknights. She is feeling socially isolated and miserable. Her arthritis is under control but she doesn’t feel she is having any quality of life outside of work. During the call the nurse establishes she is already taking folic acid 5mg 6 days a week. The next step is to suggest that she tries injecting methotrexate as this should alleviate any gastrointestinal side effects.

Oral vs subcutaneous methotrexate

Patients are often hesitant about self-injecting medication but, with reassurance and a nurse visit to teach them how to self-inject, this can be life-changing. The NRAS patients experience survey sheds light on patients’ willingness to try a different format. As many as 75% switched from oral methotrexate to using an injectable; 42% experienced a significant reduction in their side effects and nearly 50% felt as though switching had a positive impact on their quality of life. Nearly half of patients (48%) also revealed that they would have chosen the injectable route initially if they had only been given the choice.4

It is well-recognised that the clinical efficacy of subcutaneous methotrexate is superior to oral methotrexate at the same dose. Evidence also suggests that absorption is better.9 This switch in therapy format can mean patients tolerate the therapy better and are more likely to be adherent, resulting in better disease control. Subcutaneous methotrexate is more expensive than oral, and this is one of the reasons why, in general, oral is used first. Another reason oral methotrexate is the first drug used when patients are initially diagnosed is an assumption that it is better to use oral therapy than to expect patients to start injecting themselves, just as they are just getting used to their diagnosis and are having to make lots of changes in their lives.

However, the cost benefits of subcutaneous methotrexate are considerable. A UK cost effectiveness study has shown that the routine use of subcutaneous methotrexate, following oral methotrexate failure, has the potential to save an estimated £7,000 per patient in the first year of therapy and £9 million per year nationally in new patients, compared with the use of biologics.10 The important point is that patients are offered injections early if they have tolerability issues with oral, and that they know this is an option for them.

If patients are trained to self-inject in secondary care but are subsequently prescribed a different brand by their GP, and therefore a different device, this can cause confusion and affect patient confidence in self-injecting, especially if they have dexterity issues. It is therefore important to ensure that methotrexate is prescribed by the brand the patient has been trained to use.

CONCLUSION

Involving patients in the decision-making process empowers them to decide on which treatment option will most likely allow them to achieve their best adherence. A proactive consultation provides the opportunity to ensure they opt for a treatment choice that will suit their tolerability, preferences and lifestyle, thereby offering the potential to maximise their outcomes.

REFERENCES

1. NICE TA375. Adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab, certolizumab pegol, golimumab, tocilizumab and abatacept for rheumatoid arthritis not previously treated with DMARDs or after conventional DMARDs only have failed; 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta375

2. van der Heidje DM, van’t Hof MA, van Riel PLCM, et al. Development of a disease activity score based on judgement of clinical practice by rheumatologists. J Rheumatol 1993:20;579-581.

3. NICE TA715. Adalimumab, etanercept, infliximab and abatacept for treating moderate rheumatoid arthritis after conventional DMARDs have failed. Technology appraisal guidance; 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta715

4. National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society (NRAS). Patient experience survey; 2021. https://nras.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/09/RA-patient-experience-survey-analysis_NRAS-.pdf.

5. Neame R, Hammond A. Beliefs about medications: a questionnaire survey of people with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2005:44;762-767.

6. Nestoriuc Y, Orav EJ, Liang MH, et al. Beliefs about medicines predict non-specific side effects in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Care & Research 2010:62(6); 791-799.

7. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Medicines optimisation: Helping patients to make the most of medicines; May 2013. https://www.rpharms.com/Portals/0/RPS%20document%20library/Open%20access/Policy/helping-patients-make-the-most-of-their-medicines.pdf

8. NICE NG100. Rheumatoid arthritis in adults: management; 2018 (Updated 2020). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng100

9. O’Connor A, Thorne C, Kang H, et al. The rapid kinetics of optimal treatment with subcutaneous methotrexate in early inflammatory arthritis: an observational study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 2016:17;364.

10. Fitzpatrick R, Scott DGI, Keary I. Cost-minimisation analysis of subcutaneous methotrexate versus biologic therapy for the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis who have had an insufficient response or intolerance to oral methotrexate. Clin Rheumatol 2013; 32:1605-12

Related articles

View all Articles