JIA: A common and debilitating childhood disease

HEATHER SMEE

HEATHER SMEE

Registered Nurse (Child). Dip HE

Clinical Nurse Specialist,

Paediatric Rheumatology

Bristol Royal Hospital for Children

Practice Nurse 2023;53(2):16-19

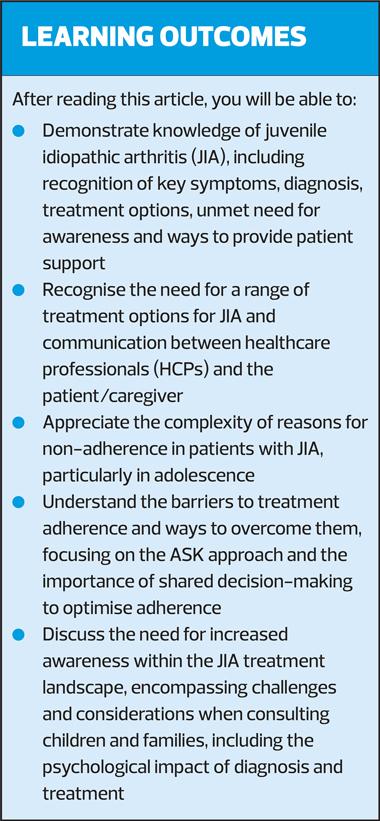

With enhanced juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) recognition training, we can reduce the time taken to achieve a JIA diagnosis, by enabling general practice nurses to spot the disease and initiate rapid GP referral, and to promote treatment adherence once a diagnosis is made

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is the most common chronic rheumatic disease in children and includes all types of chronic inflammatory arthritis of unknown aetiology with an onset age of less than 16 years.1,2 In the UK, the age-standardised incidence rate of JIA is 5.61 per 100,000, with an age-standardised prevalence of 43.5 per 100,000.2 The disease is marked by pain, swelling of the joints and reduced mobility.1,2 It is associated with significant disability, long-term damage to joints, and comorbidities including uveitis.2 Many children with JIA experience disability and limitation in their daily activities, with up to 70% estimated to have active disease into adulthood, which requires further rheumatological care and management.1,3

A diagnosis of JIA requires the persistence of arthritis for more than 6 weeks in a child under 16 years of age with no other identified cause.4,5 Inflammation of the joints results in pain, loss of function and morning stiffness.4,5 As the disease progresses, more joints may become affected.4

In the general practice setting, parents may bring up their young child’s symptoms when attending clinic for unrelated appointments, such as routine immunisations. Rather than recognising and reporting the symptoms of arthritis, parents may mention a swollen joint, joint problems or ‘growing pains’. They may have noticed their child is walking with a limp or has stopped walking soon after their first steps. For the general practice nurse, this is a key moment in the diagnostic pathway to mention to the GP to review, and refer onward to rheumatology.

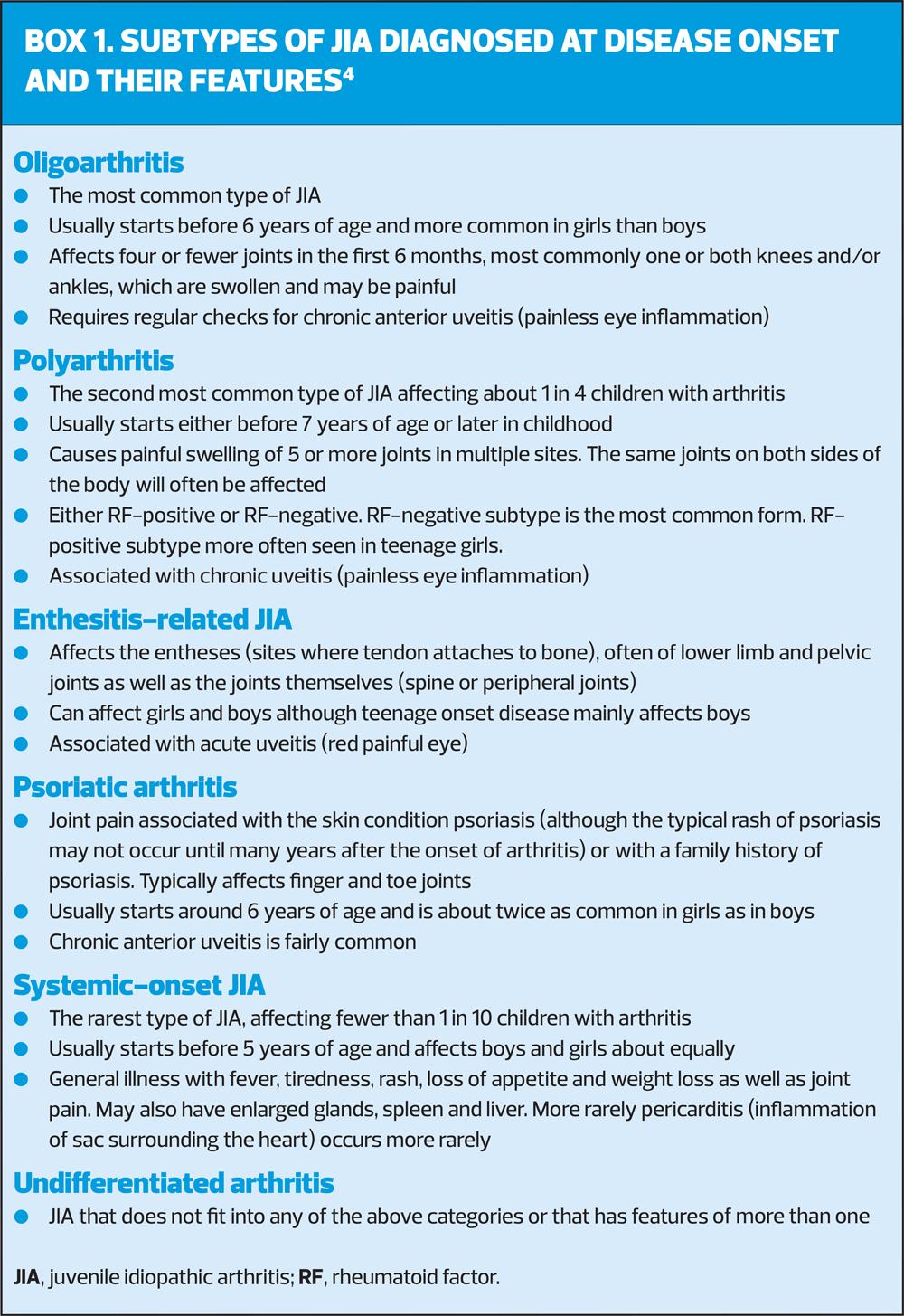

There are several distinct JIA subtypes, each characterised by a specific set of features,2,5 as shown in Box 1.5 If the disease is managed inadequately, permanent joint damage can occur.5 Physical development can be delayed significantly in young children.5 The effects of JIA are not only physical; the disease can impact emotional well-being, social development and educational attainment.5

DIAGNOSING JIA: DIFFICULTY AND DISBELIEF

Key steps in the recognition of JIA are a clinical diagnosis of inflammatory joint disease (particularly synovitis) and the exclusion of other known conditions.6,7 A JIA diagnosis is clinical, based on reported signs and symptoms rather than diagnostic testing.6,8 On examination, features suggestive of synovitis include localised joint warmth and a boggy feeling on palpitation of the joint line.6

Swelling, warmth and stiffness of a joint, occurring at the start of the day and improving with activity, are strongly indicative of JIA.6 Presentation of JIA later in life is associated with a reduced range of movement, contractures at the affected joint(s) and consequent disability.6 The paediatric Gait Arms Legs Spine (pGALS) assessment, a recently validated screening system for the musculoskeletal system in children, has proven to be a useful tool for paediatric rheumatological disease, providing quick, easy and validated assessment of a child’s joints.5,6,9

Optimal management of JIA requires early diagnosis and specialist paediatric multidisciplinary care.3,6 Ideally, referral to a specialist in paediatric rheumatology should occur within 6 weeks of symptom onset.6 A ‘window of opportunity’ has been described as an early critical period in which the natural history and inflammatory process of JIA can be altered.4 However, in practice, the identification of JIA can be a long process, with parents reporting long waiting times for referral and diagnosis due to a lack of recognition of early symptoms by both parents and physicians.3 With enhanced JIA recognition training for practice nurses, we can reduce the time taken to achieve a JIA diagnosis, by enabling practice nurses to spot the disease and initiate fast GP referral.3

TREATING JIA: EARLY AND AGGRESSIVE INFLAMMATION CONTROL

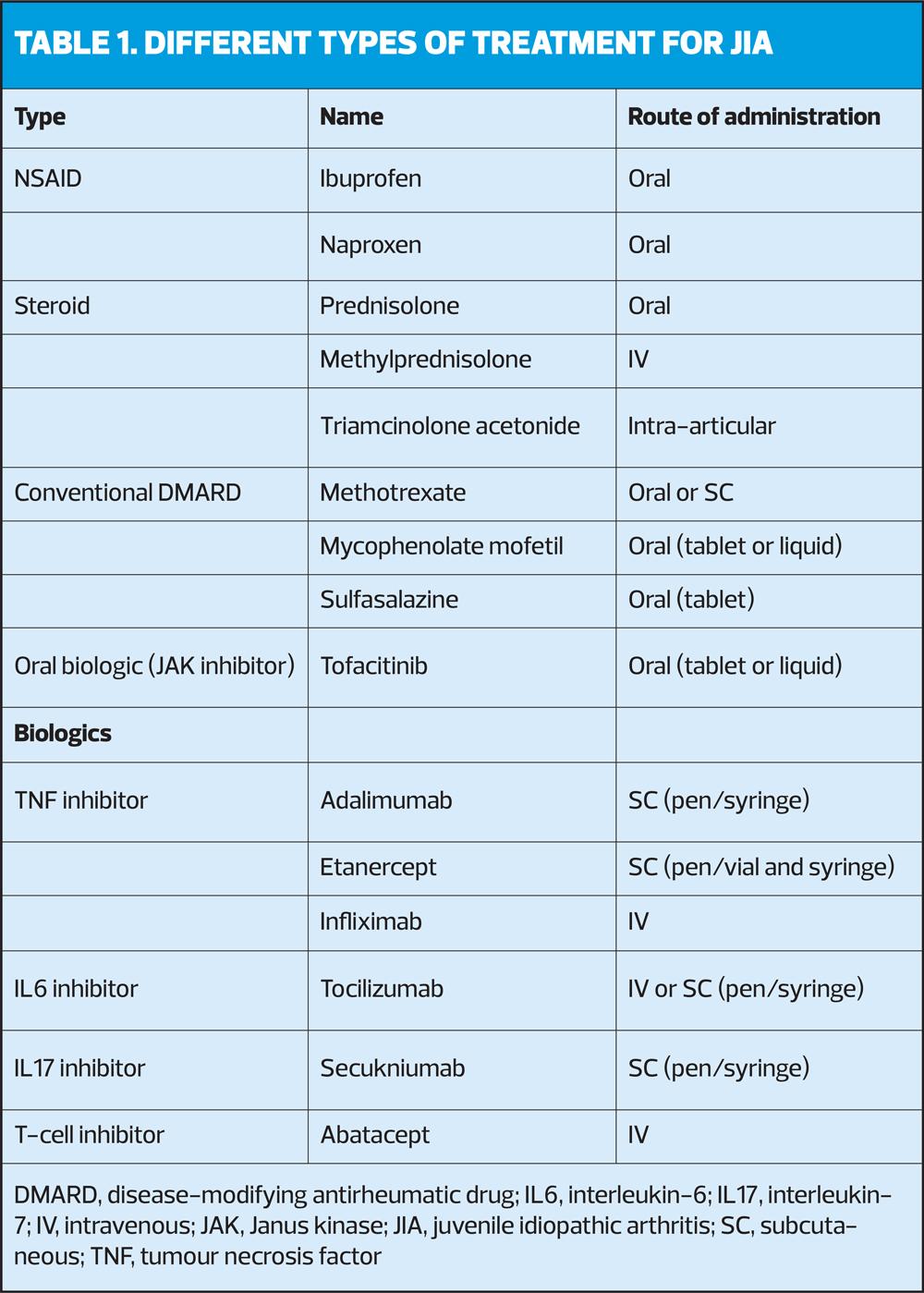

JIA treatment aims to achieve a complete absence of disease by controlling inflammation and joint pain, reducing the number of affected joints, and thus preventing long-term damage and improving quality of life.4 (See Table 1). Typical treatment follows a stepped approach, starting with a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), to reduce joint pain and stiffness.4 For particularly affected joints, or certain types of JIA, direct injection of a steroid into the joint and/or oral corticosteroids may be necessary to control symptoms.4 If these do not provide adequate control, a disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug (DMARD), such as methotrexate (MTX), can be used.4 If DMARDs do not elicit an adequate therapeutic response, biological therapy can be offered.4

There is strong evidence demonstrating the importance of aggressive and early treatment to control inflammation and the symptoms of JIA.4,6 MTX is the most widely used conventional DMARD for the management of JIA8 and is often used in conjunction with NSAIDs as a bridging therapy until MTX takes effect.4 It has an acceptable safety profile and is highly effective at achieving disease control.8 MTX can be administered both orally and subcutaneously; however, there is increased bioavailability via the subcutaneous route at higher doses, and investigators have found increased efficacy after switching from oral to subcutaneous administration.8 A patient must trial a DMARD such as MTX to become eligible for the next line of biologic medication.4 It is widely recognised that the prognosis of children with JIA has improved considerably following the arrival of MTX.2,10

COMBATTING NON-ADHERENCE THROUGH PATIENT EDUCATION

Unfortunately, treatment adherence in JIA remains a challenge. Although JIA and RA are different diseases, common issues observed in adult patients with RA are mirrored in adolescent patients with JIA.11,12 In 2022, a patient survey commissioned by the National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society (NRAS) reported that over 70% of patients had stopped taking their oral MTX.11 A survey of parents with children diagnosed with JIA reported that 25% of patients did not receive any information about treatment options at their first consultation, whilst 34% were only given information on the specific medications they were about to commence and were not made aware of any alternative treatments.12 Moreover, 26% felt they had little to no influence on their treatment choices.12

The lack of discussion regarding treatment options highlights the urgent need for increased patient awareness and education surrounding the disease, calling for a joint decision-making effort between patients, HCPs and caregivers. By recognising the priorities, experiences and values of patients and carers, treatment adherence and satisfaction can be improved.13 Shared decision-making enables patients and caregivers to understand the benefits, potential harms and outcomes of their treatment, empowering them to make choices and providing the opportunity to reach a well-informed decision about their care.14 Higher patient involvement in treatment decision-making and increased awareness of possible treatment options results in better treatment adherence and, therefore, improved symptomatic relief.12

The ASK approach

The ASK approach is a consultation format developed by NRAS. It is recommended that patients use the ASK approach to improve their consultation experience, boosting patient confidence and encouraging active participation in the treatment decision-making process.15

[BOLD] Address your main concerns at the start of the consultation[BOLD] Share details of your symptoms, prioritising those that have the most impact on your quality of life[BOLD] Know everything about your prescribed treatment, how you can take it and any other options

LIVING WITH JIA: A ROLLERCOASTER RIDE

Caring for a child with JIA has been described akin to the recurring ups and downs of a rollercoaster ride rather than distinct phases ending in resolution, with caregivers experiencing mounting anxiety, fear and confusion.16 The unpredictability of the disease and its impact on the patient highlights the need for healthcare professionals to actively support patients and caregivers, remaining vigilant of the complex emotional journeys associated with JIA. By actively recognising the effects on both physical and emotional health, HCPs can achieve improvements in satisfaction, adherence and patient outcomes.13,16

Age at diagnosis should reflect how HCPs approach care and management. It is important to be aware that younger children may not complain of pain at inflamed joints and instead, may avoid using the affected joint.6 A diagnosis in adolescence can be even more difficult, as new concerns about the future and transition into adulthood can arise during the associated move from complete dependence to a more autonomous lifestyle.1,17 Factors contributing the high level of non-adherence include being an older adolescent, complex therapies, medication with side effects and denial of illness.17

Optimal management of JIA calls for early, specialist multidisciplinary care,6 and for teens in particular, an honest, non-judgemental consultation in which concern, empathy and respect are expressed is preferred, with transparency about any possible side effects of treatment.17

CASE STUDY 1.

THE IMPORTANCE OF PATIENT EDUCATION

Jack is a 14-year-old boy who was diagnosed with polyarticular JIA at 2 years of age. He was being managed on weekly MTX, which successfully controlled his arthritis. Jack’s mum contacted his treatment team to say he had been struggling with his joints after a long period without issues; this was leading to difficulties mobilising in the morning and attending school. His mood had become low, and he was no longer able to play football.

After review, it was found that numerous of Jack’s joints were affected, necessitating treatment with steroids. Jack was very withdrawn and quiet in clinic. On discussion, Jack confessed that he had stopped taking his MTX because he had been doing well for so long that he felt he didn’t need it anymore. He didn’t want to be different to his peers and didn’t want to take medication anymore.

It became clear that Jack lacked understanding of his disease and treatment. As he had been diagnosed at 2 years old, education about JIA had been provided to his family as he was too young to have understood. Now that he had been stable for some time, the fact that Jack had grown older and was now capable of understanding his condition had been overlooked. The team were able to provide information to Jack about JIA, explaining why he needed to continue taking his medication. Following this discussion, Jack had a greater understanding of the disease and its management, and he agreed to continue taking his medication.

This case study reflects the importance of educating patients on the disease and treatment when they are older, especially those who received a diagnosis at a young age. It highlights that HCPs should be cognisant of adolescence and of how children and young adults need to feel empowered through their own knowledge.

CASE STUDY 2.

ALLEVIATING TREATMENT ANXIETY

Mary is a 6-year-old girl with known JIA, having started on oral MTX treatment around 3 months ago. She attended clinic for review after a few months on treatment. It was noted that she still had some active JIA. Her parents informed the team that they were struggling to get Mary to take the MTX orally, and each week she was becoming increasingly distressed when taking the medication; she was spitting it out, and her parents were unsure how much of it was being absorbed by her body. Mary’s parents had previously been keen for her to have liquid medication, as they were concerned about weekly injections and needle phobia, but they admitted they were now struggling with getting her to take her oral medication at all.

The team discussed with the family the importance of Mary taking medication regularly to effectively control her arthritis. Upon discussion, the nurse informed the family that the injection was available in a pen format, rather than a visible needle, alleviating any worries about needles. It was explained that injectable MTX is subcutaneous and, therefore, less painful than the intramuscular injections.

Mary and her family were shown the demonstration pen, and much to her parent’s surprise, Mary happily sat playing with this dummy device. It was agreed with the family that Mary would switch to the injectable form of MTX, which led to easier administration each week. Once she was receiving her full dose, Mary’s arthritis settled.

Mary’s case study shows how important it is to have the full picture in terms of what forms of treatment are available. An open conversation between parents and the nurse can lead to positive outcomes, which may not have been considered without collaborative discussion.

CONCLUSION

Nurses and general practice teams are an integral asset in managing children and families with JIA, from recognition and early diagnosis to ongoing management and care. As the practicing nurse, remaining vigilant of reported ‘growing pains’, swollen joints and limping is key in initiating prompt GP referral and achieving diagnosis. A faster diagnosis improves JIA outcomes. By encouraging patient involvement during decision-making processes, for example using the ASK approach, patients will feel empowered, leveraging the position of healthcare professionals to provide tailored advice to their patients.

REFERENCES

1. Cartwright T, Fraser E, Edmunds S, et al. Journeys of adjustment: the experiences of adolescents living with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Child Care Health Dev 2015 Sep;41(5):734-43.

2. Costello R, McDonagh J, Hyrich KL, Humphreys JH. Incidence and prevalence of juvenile idiopathic arthritis in the United Kingdom, 2000–2018: Results from the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Rheumatology 2022 May;61(6):2548-54.

3. Adib N, Hyrich K, Thornton J, et al. Association between duration of symptoms and severity of disease at first presentation to paediatric rheumatology: results from the Childhood Arthritis Prospective Study. Rheumatology 2008 Jul;47(7):991-95.

4. NICE TA373. Etanercept, abatacept, adalimumab and tocilizumab for treating juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Health technology appraisal 373; December 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta373

5. Davies K, Cleary G, Foster H, et al. British Society of Paediatric and Adolescent Rheumatology (BSPAR) Standards of Care for children and young people with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology 2010 Jul;49(7):1406-08.

6. McMahon AM, Tattersall R. Diagnosing juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Paediatr Child Health. 2011 Dec 1;21(12):552-7.

7. Kim KH, Kim DS. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Diagnosis and differential diagnosis. Korean J Pediatr. 2010 Nov;53(11):931.

8. Giancane G, Consolaro A, Lanni S. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Diagnosis and treatment. Rheumatol Ther. 2016 Dec;3(2):187-207.

9. Foster HE, Jandial S. pGALS – paediatric Gait Arms Legs and Spine: a simple examination of the musculoskeletal system. Pediatr Rheumatol. 2013 Dec;11(44):1-7.

10. Van Dijkhuizen EHP, Aidonopoulous O, Ter Haar NM, et al. Prediction of inactive disease in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a multicentre observational cohort study. Rheumatology 2018 Oct 1;57(10):1752-60.

11. National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society (NRAS) Patient experience survey; May 2021. https://nras.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2021/09/RA-patient-experience-survey-analysis_NRAS-.pdf

12. National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society (NRAS) May 2021. (Data on file; unpublished).

13. Min M, Hancock DG, Aromataris E, et al. Experiences of living with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a qualitative systematic review protocol. JBI Evid Synth 2020 Sep 1;18(9):2058-64.

14. NICE NG197. Shared decision making; 17 June 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng197

15. National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society (NRAS) website. ASK approach. https://nras.org.uk/resource/how-to-approach-your-rheumatology-consultation/

16. Gómez-Ramírez O, Gibbon M, Berard R, et al. A recurring rollercoaster ride: a qualitative study of the emotional experiences of parents of children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2016 Dec;14(13):1-11.

17. Taddeo D, Egedy M, Frappier JY. Adherence to treatment in adolescents. Paediatr Child Health 2008 Jan 1;13(1):19-24.