Gout: is there a role in management for the general practice nurse?

DR ANDREW FINNEY RN, Dip, BSc (Hons), PGCHE, PhD, Keele University UK.

DR ANDREW FINNEY RN, Dip, BSc (Hons), PGCHE, PhD, Keele University UK.

RACHEL VIGGARS RN Dip HE BSc (Hons) Specialist Practice – GPN

Advanced Nurse Practitioner at Ashley Surgery, North Staffordshire CCG

DR EDWARD RODDY DM FRCP

Research Institute for Primary Care and Health Sciences, Keele University

Gout is considered to be the only ‘curable’ form of arthritis yet treatment is often less than ideal and fails to follow well-established guidelines. If general practice nurses had greater involvement, could management be improved?

Gout is commonly thought of as a ‘rich man’s disease’ caused by dietary excess and overconsumption of alcohol,1 but this negative perception can lead to underestimation of its impact.2 Characterised by recurrent sudden flares of excruciating joint pain, swelling and inflammation, poorly treated gout can cause disabling joint damage and is associated with multiple comorbidities including renal impairment, metabolic syndrome, heart disease and depression.3

The prevalence of gout has increased dramatically in the UK and now affects 2.5% of the UK adult population, making it the most prevalent form of inflammatory arthritis.4,5 It is four times more common in men than women and is more common in older age groups, reaching its peak prevalence between the ages of 80-84 where it affects 15% of men and 6% of women.4

The majority of patients with gout are managed in general practice.6 Gout is considered to be the only curable form of arthritis yet GP-led treatment for gout is sub-optimal and not concordant with current national and international recommendations.4 In view of this, a new approach is required to improve the management of gout and therefore we ask ‘is there a role for the general practice nurse?’

SO WHAT IS GOUT?

Gout is a form of arthritis caused by the formation of monosodium urate crystals in and around joints. Gout results from sustained elevated serum urate (often reported as serum uric acid [sUA]) levels (hyperuricaemia) beyond a saturation point that can lead to formation and deposition of urate crystals.

Risk factors for gout include obesity, and excess consumption of beer or spirits, red meat, seafood, fructose-sweetened beverages, and fruit juices, but in many patients gout is due to genetic factors, comorbid medical conditions such as hypertension, chronic kidney disease and obstructive sleep apnoea, or to medication use (particularly diuretics) rather than life-style factors.5

Hyperuricaemia is caused by over-production or renal under-excretion of urate5. Over 90% of people with gout have hyperuricaemia because of renal under-excretion.7 Over time, the formation of monosodium urate crystals in and around the joints can trigger an acute flare. Flares usually present with an excruciatingly painful, red, hot and swollen joint(s). The skin often appears shiny.7 Acute flares come on rapidly (typically overnight) with symptoms peaking within 12–24 hours and usually subsiding within 1–2 weeks.7

Gout most commonly affects the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint but can also present in other joints within the foot as well as the knees, ankles, elbows and hands.8 It usually affects a single joint at a time, but several joints can be affected at once (polyarticular gout). Monosodium urate crystals can also form outside of the joint and under the skin forming discrete firm lumps called tophi.8 Gout can also cause chronic joint pain and erosive destructive arthritis.

DIAGNOSING GOUT

Diagnosis is most commonly based on symptoms, clinical history and an examination of the affected joint or joints. An acute flare in one joint with excruciating pain that peaks within 24 hours is highly characteristic of gout, particularly when the first MTP joint is affected.8 When diagnostic uncertainty exists, joint aspiration and microscopy of synovial fluid can give a definitive diagnosis. Although the serum urate level is elevated in people with gout, it should be noted that serum urate on its own is not a useful diagnostic test as most people with hyperuricaemia do not have gout and serum urate can be falsely low when measured during an acute flare.9

MANAGEMENT

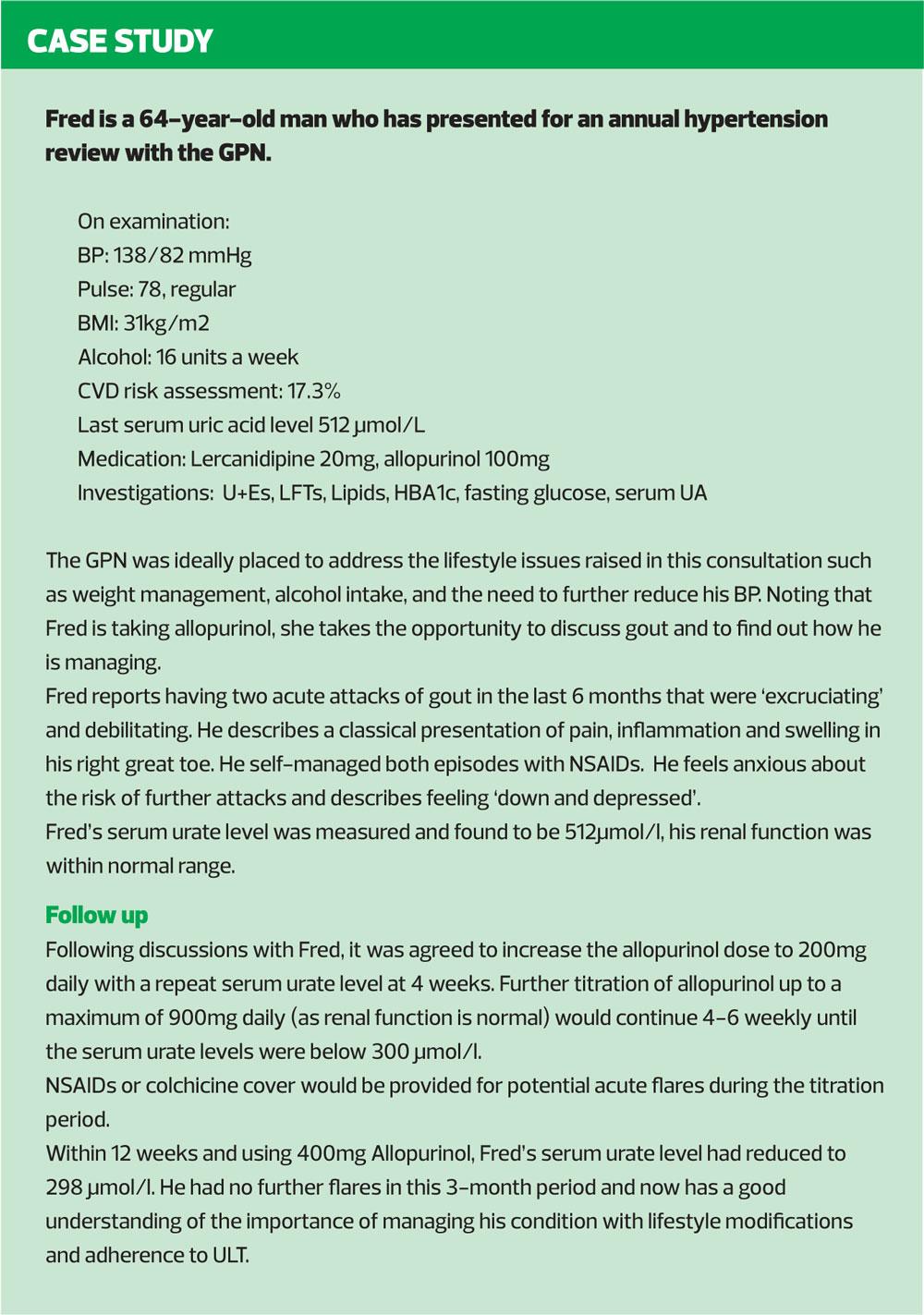

Due to the extreme pain associated with acute flares, all patients should be offered or advised to use analgesia that is commenced as early as possible. Treatment options include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) (such as naproxen) with a proton-pump inhibitor, low-dose colchicine, or oral corticosteroids, according to patient preference, past experiences and comorbidities. Non-pharmacological treatment such as ice-packs placed over the affected joint can be useful adjunctive therapy.10

The BNF recommends that colchicine should be used in doses of 0.5mg two to four times daily. Diarrhoea is a common side effect at higher doses. Colchicine is associated with drug interactions with ciclosporin, ketoconazole, ritonavir, clarithromycin, erythromycin, verapamil and diltiazem. Statins should be stopped while taking colchicine.11 Oral prednisolone at a dose of 30-35mg for five days has been shown to be as effective as NSAIDs.7

Gout is often viewed as an acute episodic condition, which results in a focus on the short-term treatment of acute flares and detracts from ‘curative’ long-term management of the condition and therefore, the most serious complications are not prevented.2 Monosodium urate crystals can be eliminated through a combination of effective patient education and evidence-based ‘treat-to-target’ urate-lowering therapy (ULT) such as allopurinol.6

Long-term use of ULT is strongly recommended when patients have recurrent flares, tophi or chronic arthritis, but recently updated British and European guidelines advocate that the benefits of ULT should be explained and offered to all patients at diagnosis.12 Optimal ULT involves a treat-to-target approach to reduce serum urate below the physiological saturation threshold, thereby preventing further crystal formation and dissolving existing crystals to prevent further flares. European and American guidelines recommend lowering serum urate below 360?mol/l,12,13 whereas the British Society for Rheumatology (BSR) advocates a more stringent target below 300µmo/l which leads to more rapid clinical improvement.14

Allopurinol should be commenced at an initial dose of 100mg per day (50mg per day in the presence of stage-4 chronic kidney disease [CKD]) with a gradual monthly increase in dose (50/100mg increments) until the therapeutic target is achieved. The maximum daily dose of allopurinol is 900mg in divided doses, but the maximum daily dose in patients with renal impairment is 100mg.11

Despite clear guidance and recommendations, only 30-40% of people with gout take ULT and only 40% of those that do have the dose escalated to achieve the 360?mol/l target.15,16 Suboptimal treatment causes frequent flares, chronic pain and disability, long-term joint damage, and impaired quality of life.6

MONITORING AND FOLLOW-UP

Once ULT has been commenced patients should be followed up and monitored every 4-6 weeks with regular serum urate measurements until the target serum urate level has been achieved, and then annually as part of on-going care. Patients may still experience acute flares during the first two years after the target serum urate level is reached while existing crystal deposits dissolve, but these flares should eventually cease.6 The critical serum urate level (the saturation point) is 360µmo/l although this will show as ‘in range’ and within normal limits on practice computer screens, so it is crucial to know whether or not serum urate is above or below this critical level.8

IS THERE A ROLE FOR THE GPN?

The BSR guideline was updated in 2017 to reflect the availability of the new pharmacological treatments, increases in incidence and prevalence, sub-optimal management in both primary and secondary care, and a better understanding of barriers to effective care.14

BSR targets three key areas:14

- Management of acute attacks

- Modification of lifestyle and risk factors

- Optimal use of urate-lowering therapy

How GPNs might best become involved in the management of gout is not certain, but there are sufficient parallels with the treat-to-target approach in conditions such as diabetes to suggest that similar approaches could work. Gout information should be tailored to the individual patient, targeting its management, modification of lifestyle and risk factors, and initiation and upward dose titration of ULT as recommended by BSR. GPNs already have these skills but may not have the knowledge to apply them in gout. However, a nurse-led approach to the management of gout has been tested,17 and a recently-completed UK community-based randomised controlled trial demonstrated that nurse-led care of people with gout can be superior to standard GP care,18 and such a model of care is likely to be cost-effective.

CONCLUSION

Alongside the updated guidelines,12–14 two recent studies have demonstrated that suitably trained nurses can manage gout effectively.17,18 Nurse-led care should include individual patient education and patient involvement in management decisions to improve lifestyle and treat-to-target ULT adherence. GPNs are in a unique position to make a difference for patients with gout and should be encouraged to ‘take the first step’ to contribute to improving management of this painful and common condition.

REFERENCES

1. Richardson JC, Liddle J, Mallen CD, et al. A joint effort over a period of time: factors affecting use of urate-lowering therapy for long-term treatment of gout. BMC Musculoskeletal Disord 2016;17:249

2. Punzi L (2017) Change gout: the need for a new approach. Minerva Medica 2017;108(4):341-349

3. Stamp LK, Chapman PT. Rheumatology 2013;52(1):34-44

4. Kuo CF, Grainge MG, Mallen CD et al (2015) Rising burden of gout in the UK but continuing suboptimal management: a nationwide population study. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:661–667.

5. Roddy E, Choi HK. Epidemiology of gout. Rheum Dis Clin N Am 2014;40(2):155-175.

6. Rees F, Doherty M (2014) Patients with gout can be cured in primary care. The Practitioner 2014;258(1777):15-19

7. Roddy E, Mallen CD, Doherty M. Clinical review: gout. BMJ 2013;347:f5648

8. Arthritis Research UK. Gout, 2017 https://www.arthritisresearchuk.org/arthritis-information/conditions/gout/symptoms.aspx

9. Roddy E. Gout: presentation and management in primary care. Arthritis Research UK. Hands On: Reports on the Rheumatic Diseases 2011;6. https://www.arthritisresearchuk.org/health-professionals-and-students/reports/hands-on/hands-on-summer-2011.aspx

10. Schlesinger N, Detry MA, Holland BK et al (2002) Local ice therapy during bouts of acute gouty arthritis. J Rheumatol 2002;29(2):331-334

11. NICE BNF. Gout. https://bnf.nice.org.uk/treatment-summary/gout.html

12. Richette P, et al. 2016 updated EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of gout. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76, 29-42

13. Khanna D et al (2012) 2012 American College of Rheumatology Guidelines for the management of Gout part 2: Therapy and anti-inflammatory prophalaxis of acute gouty arthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2012;64(10):1447-61 https://www.rheumatology.org/Portals/0/Files/Gout_Part_2_ACR-12.pdf

14. Hui M, et al. Management of Gout: British Society of Rheumatologists, 2017

15. Roddy E, et al. Concordance of the management of chronic gout in a UK primary-care population with EULAR gout recommendations. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:1311-1315

16. Rees F, Jenkins W, Doherty M. Patients with gout adhere to curative treatment if informed appropriately: proof-of-concept observational study. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:826-30

17. Abhishek A, Jenkins W, La-Crette J, et al. Long-term persistence and adherence on urate-lowering treatment can be maintained in primary care: 5-year follow-up of a proof-of-concept study. Rheumatol 2017;56(4):529-533

18. Doherty M, et al. Nurse-led care versus general practitioner care of people with gout: A UK community-based randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2017;76 (Suppl2):167 https://ard.bmj.com/content/76/Suppl_2/167.1