Fibromyalgia: are the nuances delaying diagnosis?

Julie Lennon

Julie Lennon

RGN, BSc(Hons), PG Cert, PG Dip.

Education for Health Trainer; NHS National Education for Scotland Education Advisor and Education Supervisor; Advanced Nurse Practitioner, Gairloch

Diagnosing fibromyalgia can be challenging. The complexities and variability of symptoms at presentation means the approach requires ingenuity, and consideration and investigation of differential diagnosis

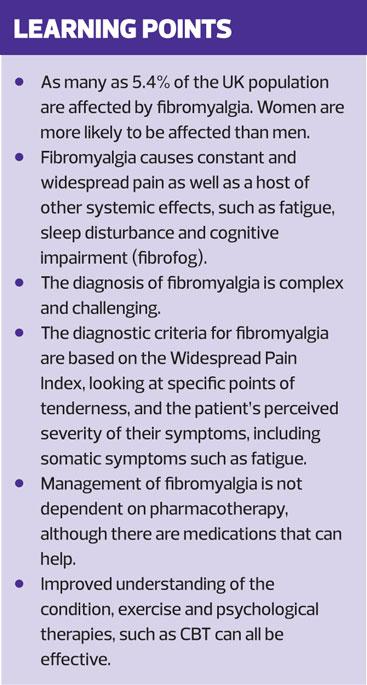

Fibromyalgia presents a considerable burden, with a worldwide prevalence in the general population of more than 2%. UK statistics suggest that its prevalence may be as high as 5.4%. Women are adversely represented in the statistics, with risk increasing in middle age and then declining.1 The impact of the condition on the workforce is difficult to determine. There are few studies that have examined the employment outcomes but sickness absence, reduced performance and possible injury can lead to loss of livelihood.2 However, a link between fibromyalgia and compensation has not been demonstrated.

CAUSES AND CONFOUNDING CONDITIONS

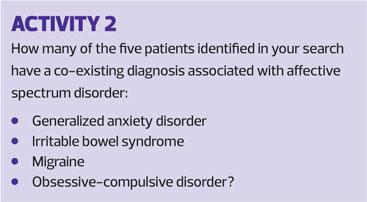

Genetic research has shown familial aggregation of fibromyalgia and major depressive disorder. Two studies suggest that fibromyalgia is one member of a proposed group of psychiatric and medical disorders referred to as Affective Spectrum Disorder (ASD).3,4

When one adopts a patient-centric approach the epidemiology of fibromyalgia and the commonality of its symptom profile with other pain phenotypes merits examination. A heightened sensitivity to pain is common to fibromyalgia, chronic widespread pain and chronic fatigue syndrome (also known as chronic myalgic encephalomyelitis [ME]).5 It has been argued that consideration should be given to clear, qualitative differences between chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia. Differences, such as response to exercise and sleep patterns, have been shown to produce different outcomes between the conditions.6 The Central Sensitisation Hypothesis, described as amplification of pain sensation originated by the central nervous system, is a common overlapping theme of these conditions, thus making diagnosis more complex.

It has been argued that fibromyalgia is a non-articular condition and that inflammatory changes are not a marker of this syndrome.7 This has been challenged in a seminal work looking more comprehensively at 92 inflammation related proteins, rather than previous work focusing on a few pre-determined inflammatory markers.8 Though there are limitations to this study, with a study cohort of only 40 patients, the results demonstrated evidence of neuro-inflammation and chronic systemic inflammation. More discussion is needed to stimulate further research in this area.

PRESENTATION

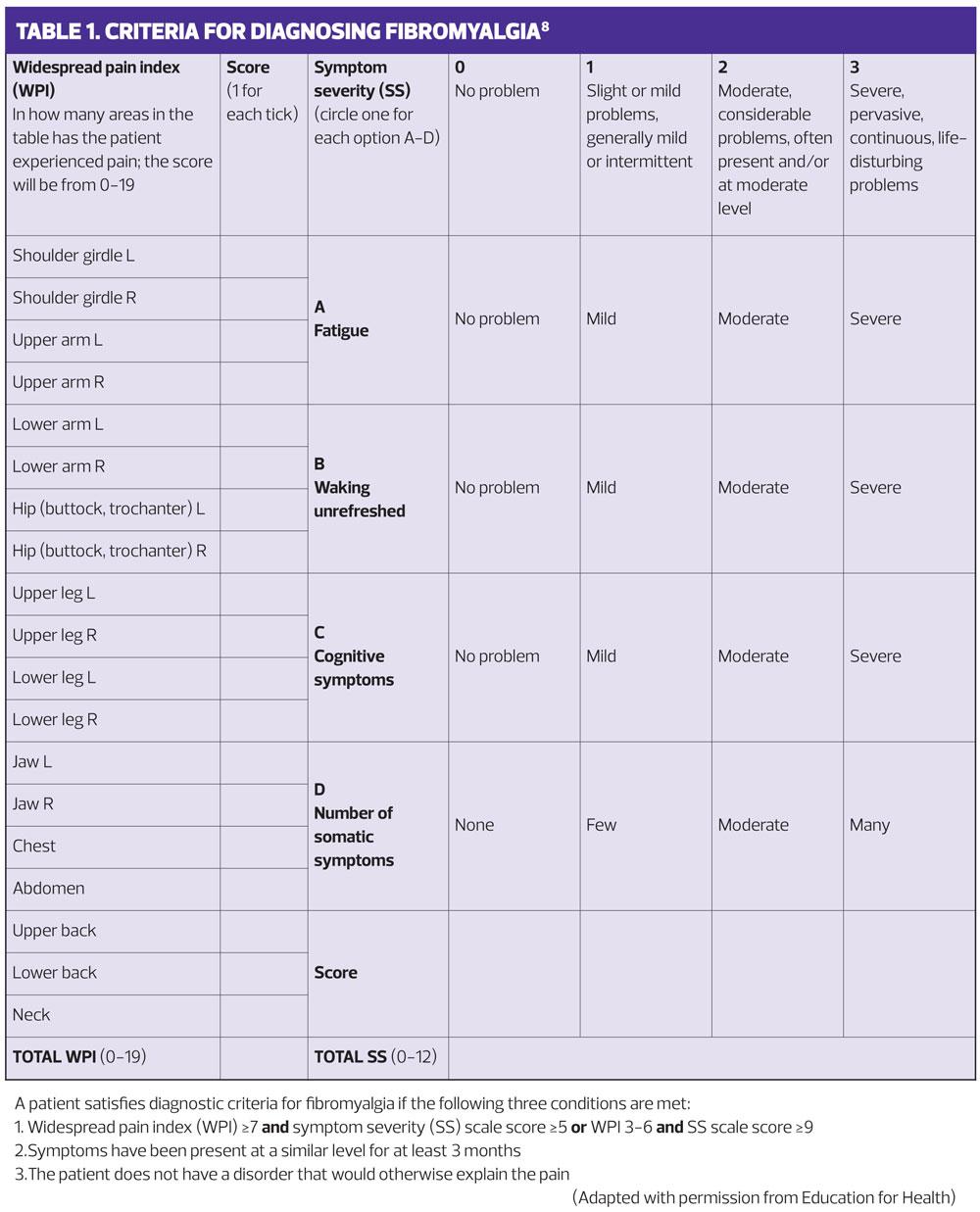

Fibromyalgia, often referred to as a ‘chronic pain syndrome’, is characterised by widespread pain, felt across the whole body and with multiple ‘tender points’. These are the overriding features of fibromyalgia and are the basis of the diagnostic criteria.8 (Table 1)

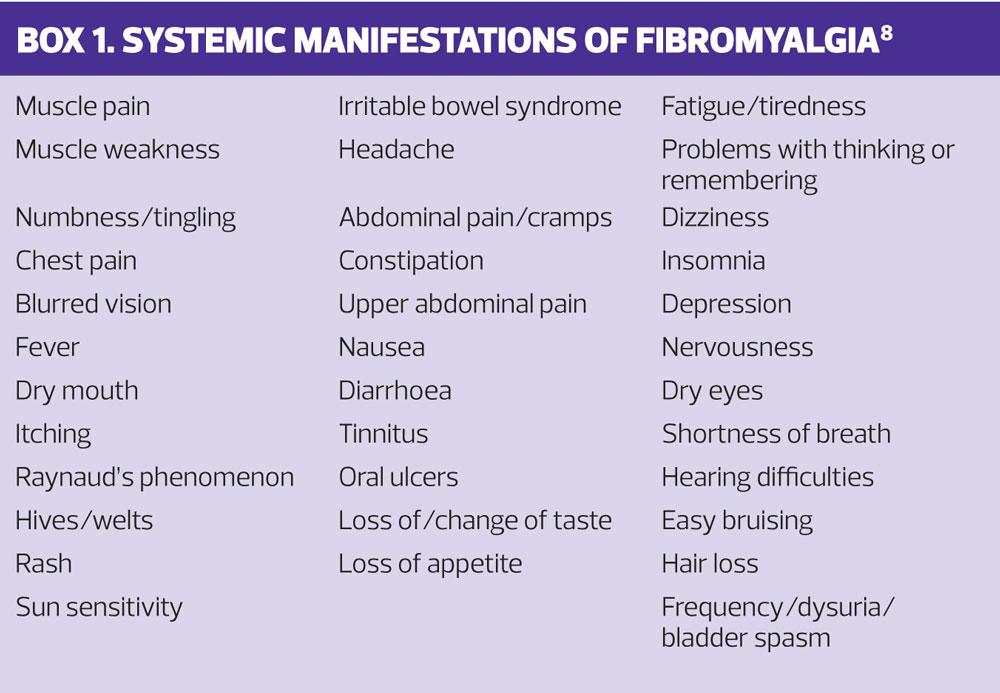

Systemic manifestations of fibromyalgia are multiple, diverse and also often identified. (Box 1) Patients with fibromyalgia can present with sleep disorder. Increased waking, allied with reduced rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, results in nonrestorative sleep.9 The associated cognitive impairment or ‘fibrofog’, manifesting as difficulty remembering things, adds to the distress. The principle symptoms of fibromyalgia can be identified by applying the pneumonic FIBRO:10

- Fatigue and Fog: cognition

- Insomnia: non-restorative sleep

- Blues: anxiety and depression

- Rigidity: muscle and joint stiffness

- Ow!: widespread pain and tenderness.

Combined with widespread pain there is amplification of pain sensitivity – hyperalgesia – thought to be due to neurobiological variations, resulting in deregulation of processes normally employed to control pain sensation.10

DIAGNOSIS

Diagnosis currently should be considered after structured examination of the patient, focusing on the current clinical presentation. It is important to have a systematic approach so that no area of the clinical presentation is overlooked. Principal to establishing a diagnosis is to take a history of the presenting complaint using open questions, such as ‘How long have you had this pain?’, and then clarifying all responses with closed questions. Fibromyalgia presents with widespread pain for at least three months. Descriptors consistent with neuropathic pain, such as pricking, tingling, burning or stabbing, are often offered by the patient.

Practical criteria for improving recognition for fibromyalgia were originally proposed in 1990 and required tenderness on pressure on ‘tender points’ in 11 of 18 specified sites.11 Though originally welcomed, the limitations to this approach soon became evident. The examination of the tender points was not always performed with vigour and accuracy,12 and clinical skills in the examination of tender points was sub-optimal.13 The current diagnostic criteria (Table 1) identify associated symptoms and severity and no longer rely on examination of tender points but engage the patient, using self-awareness of pain and severity over the preceding week.8 The number of sites has increased from 18 in the original classification to 19.

The somatic symptoms associated with fibromyalgia also needed a more comprehensive approach. This is recognised in the current, updated scale, which acknowledges that fibromyalgia is more than excessive levels of widespread pain. It encompasses symptom severity and offers a more holistic assessment of both the presenting pain and the somatic symptoms.

Pain is a complex phenomenon and a comprehensive structured assessment can be carried out, using the mnemonic SOCRATES:

- Site: where is the pain?

- Onset : when did it start? How long ago?

- Character: aching, stabbing, burning, crushing?

- Radiation: where does it go to?

- Associated features; headache, fatigue?

- Time course: does the pain follow any pattern?

- Exacerbating/relieving features: what makes it worse? What makes it better?

- Severity: how bad is the pain on a scale of 1-10?

Adopting an holistic approach to musculoskeletal pain will add rigor to the diagnosis, and it should cover: site, character, aggravating and relieving factors, current stiffness and swelling, the pattern and number of trigger points involved, symptom severity, family history and exploration of an acute or chronic presentation (lasting more than 3 months).

Following the structured history, the criteria for diagnosing fibromyalgia should be used. (Table 1)

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES AND RED FLAGS

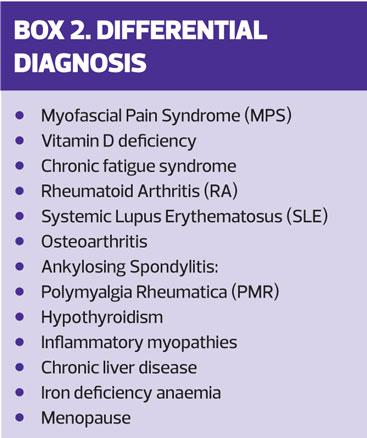

The list of potential differential diagnoses is long (Box 2) and establishing a firm diagnosis of fibromyalgia is complex. As with all other areas of your practice, it is vital that you are aware of and work within the limits of your expertise.

Red flags indicating serious underlying pathology, e.g. rash indicating systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), or dry eyes consistent with Schogren’s syndrome, should be considered and appropriate prompt treatment or referral undertaken. Further investigations are indicated by the history and examination findings, with additional tests being considered for an unusual presentation or when a differential diagnosis is suspected.

CASE STUDY

Carol, aged 39, presents with widespread ‘gnawing type’ pain across her back, arms and legs. She has the associated symptom of stiffness in all limbs, though this is worse in her hands and wrists, and this adds to her distress. She complains of occasional headaches and co-proxamol (which she was given for musculoskeletal pain) appear to help for a short period, but the headache then returns.

Her symptoms started more than 1 year ago and appear to be related to a fall in her garden. She has become more lethargic over the last 6-9 months, stating that she often wakes during the night and never feels as if she has had a good night’s sleep. She also confirms that she finds processing information more difficult and wonders if her symptoms are related to the menopause. Carol has a previous history of depression and high alcohol consumption. Her mother had been given a diagnosis of fibromyalgia during her menopause, aged 52 years.

The Fibromyalgia Diagnostic Criteria (Table 1) confirmed a Widespread Pain Index (WPI) score of 12 and a Symptom Severity (SS) score of 10. Differential diagnoses were considered during the structured history taking, but no other alternative diagnosis for the pain and associated symptoms was indicated.

In order that an alternative explanation for Carol’s symptoms could be excluded the associated features of each possible differential diagnosis was explored: e.g. hot sweats and changes to the menstrual cycle in order to exclude menopause as a cause of the symptoms; early morning stiffness lasting more than 30 minutes to exclude inflammatory arthritis, etc.. Although there are no radiological or laboratory tests for fibromyalgia – the diagnosis rests on the findings of a structured and methodical clinical history and subsequent examination findings – further investigations, such as blood tests, would be used in case of diagnostic uncertainty. It is important to bear in mind that fibromyalgia can exist with other conditions and a concomitant diagnosis may require investigation.

MANAGEMENT OPTIONS

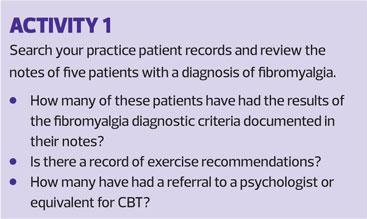

Pharmacological therapy is not mandatory for fibromyalgia. Non-pharmacological therapies such as education, exercise and cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) have been shown to be effective. A structured management programme, highlighting the benefits of education, appropriate medication, exercise and CBT, or all four, are advocated.14

Using the acronym ICE – ideas, concerns and expectations – can promote person centred care: what is important to the patient rather than what is important for the patient. Fibromyalgia can be managed but not cured. The patients’ perceptions of the disease trajectory, their concerns or beliefs of the role and purpose of drug therapy needs to be exposed so that expectations can be managed.

The Health Belief Model (HBM),15 postulates that six paradigms predict behaviour:

1. Perceived susceptibility

2. Perceived severity

3. Perceived benefits

4. Perceived barriers

5. Cues to action

6. Self-efficacy.

We can use the key constructs of the HBM to ensure that we deliver the person-centred care that engages with the patient and identifies their beliefs and expectations of both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions.

Knowledge and understanding

The patient’s prior understanding of fibromyalgia needs exploration. You will need to explore the psychological, physical and emotional impact the condition is having in order to improve their knowledge and understanding. Your knowledge of the current evidence and research will facilitate these discussions.

Exercise

Fibromyalgia can restrict mobility. Encouragement to participate in a personalised exercise regime can be effective.10 Exercises such as muscle stretching have been shown to improve physical performance and pain while resistance training can be effective in reducing depression.16 A suggested mechanism for the effectiveness of exercise interventions is that exercise acts as a natural anti-inflammatory agent, reducing the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.17

Psychological approaches

Interventions that encourage emotional exposure of the burden of fibromyalgia can also be effective. A study examining the effectiveness of CBT, focussing on cognitive restructuring and coping versus recommended pharmacological therapy or treatment as usual i.e. standard care offered by GPs, found that CBT was more successful in key areas, including function and quality of life.18 The additional outcome of improvement in pain, catastrophising and pain acceptance, strengthens its position as an effective management strategy.

Pharmacotherapy

Patients covet symptom relief. BMJ Best Practice offers an algorithm for pharmacological management.19 (See Resources and Further Reading)

The tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline, 10mg–70mg at bedtime, is thought to influence chronic neuropathic pain and is positioned as first line therapy. An alternative is cyclobenzaprine 5mg–30mg at bedtime. Cyclobenzaprine is related to the tricyclic antidepressants and is a centrally acting skeletal muscle relaxant.

Secondary pharmacological options offer a more comprehensive selection, including:

- Duloxetine (serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor [SNRI]) 30mg–60 mg daily

- Milnacipran (SNRI) 12.5mg daily, increasing to 50mg–100mg twice daily

- Pregabalin (gabapentinoid) 75mg–225mg twice daily, maximum 450mg daily

- Gabapentin (gabapentinoid) 300mg daily, titrating the dose according to response up to 1800mg–2400mg daily in three divided doses

Tertiary options are available.

Some patients benefit from monotherapy while others may require two or three drug classes for improved management. Vigilance regarding adverse effects of SNRIs and gabapentinoids is required. As with any drug, adverse reactions need to be reported via the Yellow Card Scheme.

DISCUSSION POINTS

Meta-analysis of 18 case controlled studies identified a strong association between fibromyalgia and physical and sexual abuse, in both childhood and adulthood The analysis concluded that there was no association between fibromyalgia syndrome and emotional abuse.20 There were limitations to the results of this meta-analysis, confounded by the quality of the studies. However, because the association between fibromyalgia syndrome and abuse is robust, the authors support screening for a history of abuse until rigorous prospective studies measuring the impact of abuse in childhood are available.

There is compelling evidence of a genetic component in fibromyalgia, with an eight-fold risk of developing fibromyalgia if the individual has a first degree relative with the condition.21 Primary care often has the advantage of knowing the family and its dynamics. The use of structured questions about the family history would be of considerable help in reaching a diagnosis.

CONCLUSION

The heterogeneity of the possible interventions in fibromyalgia may make it difficult to measure their effectiveness in terms of clinical outcomes in practice. However, negotiating with the patient their preferred intervention and supporting them with regular review may help symptom control.

There is currently no cure for fibromyalgia but improved recognition and understanding of it will serve to broaden our awareness and enable us to better help people suffering from this disabling condition.

REFERENCES

1. Fayaz A, Croft P, Langford RM, et al. Prevalence of chronic pain in the UK: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population studies. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010364 http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/bmjopen/6/6/e010364.full.pdf

2. NHS Plus. Occupational Aspects of the Management of Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: a National Guideline, 2006 www.nhshealthatwork.co.uk/image/library/files/Clinical%20excellence/CFS_full_guideline.pdf

3. Hudson JI, Mangweth B, Pope HG Jr, et al. Family study of affective spectrum disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60(2):170-7 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12578434

4. Hudson JI, Arnold LM, Keck PE Jr, et al. Family study of fibromyalgia and affective spectrum disorder. Biological Psychiatry 2004;56(11):884-91 http://www.biologicalpsychiatryjournal.com/article/S0006-3223(04)00895-9/fulltext

5. Norris T, Doere K, Tobias JH, Crawley E. Chronic Fatigue Syndrome and Chronic Widespread Pain in Adolescence: Population Birth Cohort Study. J Pain 2017;18(3):285-94 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5340566/

6. Abbi B, Natelson BH. Is chronic fatigue syndrome the same illness as fibromyalgia: evaluating the “single syndrome” hypothesis. QJM 2013; 106(1):3-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3527744/

7. White KP, Harth M. Classification, epidemiology and natural history of fibromyalgia. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2001; 5(4): 320-9

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11916-001-0021-2

8. Backryd E, Tanum L, Lind AL, et al. Evidence of both systemic inflammation and neuroinflammation in fibromyalgia patients, as assessed by a multiplex protein panel applied to the cerebrospinal fluid and to plasma. J Pain Res 2017;10:515-25. https://www.dovepress.com/evidence-of-both-systemic-inflammation-and-neuroinflammation-in-fibrom-peer-reviewed-fulltext-article-JPR.

9. Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, et al. The American College of Rheumatology Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia and Measurement of Symptom Severity. Arthritis Care Res 2010; 62(5): 600-10. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.20140/full

10. Branco J, Atalaia A, Paiva T. Sleep cycles and alpha-delta sleep in fibromyalgia syndrome. J Rheumatol 2014;21(6):1113-7 www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7932424.

11. Boomershine CS. Fibromyalgia: the prototypical central sensitivity syndrome. Curr Rheumatol Rev 2015;11(2):131–145. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26088213.

12. Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia: a report of the multicentre Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum 1990;33:160–172.

13. Fitzcharles MA, Boules P. Inaccuracy in the diagnosis of fibromyalgia syndrome: analysis of referrals. Rheumatology 2003;42:263–267. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12595620.

14. Buskila D, Neumann L, Sibirski D, Shvartzman P. Awareness of diagnostic and clinical features of fibromyalgia among family physicians. Fam Pract 1997;14:238–41. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9201499.

15. Goldberg DL, Burckhardt C, Crofford L. Management of Fibromyalgia Syndrome. JAMA 2004;292(19):2388–95 https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/199786.

16. Glanz K, Bishop BD. The Role of Behaviour Science Theory in Development and Implementation of Public Health Interventions. Annu Rev Public Health 2010;31:399-418 http://www.annualreviews.org/doi/full/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103604?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori%3Arid%3Acrossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3Dpubmed.

17. Assumpcao A, Matsutani LA, Yuan SL, et al. Muscle stretching exercises and resistance training in fibromyalgia: which is better? A three-arm randomized controlled trial. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 2017 Nov 29. DOI: 10.23736/S1973-9087.17.04876-6 https://www.minervamedica.it/en/journals/europa-medicophysica/article.php?cod=R33Y9999N00A17112902.

18. Sanada K, Díez MA, Valero MS, et al. Effects of non-pharmacological interventions on inflammatory biomarker expression in patients with fibromyalgia: a systematic review. Arthritis Res Ther 2015;17:272 https://arthritis-research.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13075-015-0789-9.

19. Alda M, Luciano JV, Andres E, et al. Effectiveness of cognitive behavioural therapy for the treatment of catastrophisation in patients with fibromyalgia: a randomised controlled trail. Arthritis Res Ther 2011;13(5):R173 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3308108/

20. BMJ Best practice. Fibromyalgia treatment algorithm. 2017 http://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/187/treatment-algorithm.

21. Häuser W, Kosseva M, Üceyler N, et al. Emotional, physical and sexual abuse in fibromyalgia syndrome: A systematic review with meta-analysis. Arthritis Care Res 2011;63(6):808-20. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/acr.20328/full.

22. Arnold LM, Hudson JI, Hess EV, et al. Family study of fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50(3):944-52 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.20042/full.

Related articles

View all Articles