Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency: what you ‘need to know’

Beverley Bostock-Cox

Beverley Bostock-Cox

RGN MSc MA QN

Nurse Practitioner Mann Cottage Surgery, Moreton in Marsh

Education Lead, Education for Health, Warwick

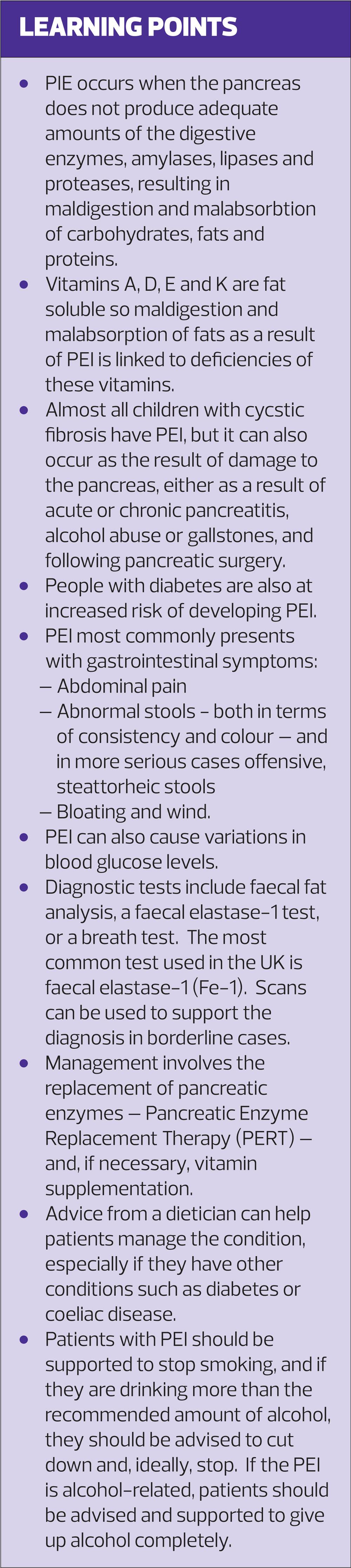

General practice nurses need to be aware of the link between pancreatic exocrine insufficiency and other long term conditions such as coeliac disease and diabetes. But what is it? This article will examine PEI: its definition, diagnosis and management

WHAT IS PANCREATIC EXOCRINE INSUFFICIENCY?

The pancreas has both exocrine and endocrine functions. The endocrine activity relates to the production of the hormones insulin and glucagon. These are secreted directly into the blood stream in order to regulate blood glucose levels. The exocrine activity relates to the production of digestive enzymes (amylases, lipases and proteases). These are delivered into the gut via the pancreatic duct system and act directly in the gut to support digestion.1

Depending on the cause of PEI, there may also be a reduction in bicarbonate output which further impacts on fat digestion.2

PEI occurs when the pancreas does not produce adequate amounts of these digestive enzymes, resulting in suboptimal digestion of carbohydrates, fats and proteins. Vitamins A, D, E and K are fat soluble so maldigestion and malabsorption of fats is linked to deficiencies of these vitamins.3

PEI can occur as the result of cystic fibrosis (CF): almost all children with CF also have PEI.4 However, it can also occur as the result of damage to the pancreas – e.g. in people with a history of acute or chronic pancreatitis which may occur as a result of alcohol abuse or gallstones. PEI can also occur following pancreatic surgery. Changes to the structure of the pancreas or ducts, such as would be seen in pancreatic tumours or strictures, may also be implicated.3

There also seems to be a link between PEI and diabetes. People with diabetes appear to be at greater risk of PEI than the general public. The pancreases of people with diabetes are known to have a greater prevalence of pancreatic fibrosis and inflammation. It is something of a ‘chicken and egg’ situation, however, as it is not clear which comes first – the pancreas damage followed by diabetes and PEI, or the other way around. People with type 1 diabetes seem to be at greater risk than those with type 2 diabetes.5

It is easy to see that anyone who has lost pancreatic tissue through surgery will be at increased risk of both diabetes and PEI. Around 1 in 10 people with diabetes will have the condition as a result of pancreatic damage, and this damage is also linked to PEI. Importantly, this is type of diabetes is not typical type 2 diabetes and should not be classified as such. It is sometimes referred to as type 3c diabetes.6

DIAGNOSIS

Signs and Symptoms

People with PEI may suffer from a range of signs and symptoms. As a result of the abnormal levels of digestive enzymes they may have:

- Gastrointestinal symptoms, such as abdominal pain

- Abnormal stools – both in terms of consistency and colour

- Bloating and wind

- Variations in blood glucose levels.

The more severe the loss of pancreatic exocrine function, the worse the symptoms tend to be, with offensive steatorrhoeic stools which may float or stick to the bowl.

Differential diagnosis is important, as there are many other causes of diarrhoea and gastrointestinal symptoms, some of which, such as gastroparesis, are directly linked to diabetes but may not be PEI.7 Coeliac disease may also mimic PEI and yet, confusingly, the two conditions are also linked. People with a history of coeliac disease are at increased risk of PEI.8

For GPNs the link between PEI and other long term conditions should be borne in mind when reviewing people with conditions such as coeliac disease and diabetes. You should always be aware of the possibility of PEI in patients exhibiting gastro-intestinal symptoms, weight loss and nutritional deficiencies, such as low vitamin D levels.

Diagnostic testing

If PEI is suspected, there are several tests that can be used to confirm the diagnosis. These include faecal fat analysis, a faecal elastase-1 test, or a breath test. The most common test used in the UK is faecal elastase-1 (Fe-1).

An Fe-1 result of <200 µg/g may indicate PEI, with values <100 µg/g indicating significant PEI. 200–250 µg/g is a borderline result so retesting may be recommended if symptoms are present but, in general, levels of 200-500 µg/g are considered to be normal. Results may, however, be unreliable if the patient has very loose stools, so ideally the test should be done on a firm(er) sample where possible.

If the test suggests PEI, further assessment can also be carried out by scan. However, in some people, where the history is highly suggestive of PEI, for example because of a previous pancreatic surgery, the diagnosis may be made on the basis of the strong likelihood, without the need for further testing.9

TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT

Pancreatic Enzyme Replacement Therapy (PERT)

If PEI is suspected and/or confirmed, digestive enzyme replacement, containing amylase, protease and lipase can help to treat the condition. The aim of treatment is to improve symptoms and reduce the impact of the malabsorption of vitamins that is the fallout of PEI.9 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that although PERT is indicated to correct PEI and malnutrition in chronic pancreatitis, further studies are required to determine optimal regimens, the impact of health inequalities and the long-term effects on nutrition.10

PERT (or pancreatin) is prescribed as oral capsules, granules or powder. Information on the different options may be found at https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/. If more than one capsule is prescribed per meal, the capsules should be spaced out through the meal. PERT capsules should not be broken or crushed before swallowing and hot drinks should be avoided as they can reduce the effectiveness of the treatment. There is a granule form available for young children but, PERT granules can irritate the oral mucosa, potentially leading to mouth ulcers, so it is important that the treatment is taken with something acidic, such as apple juice, to mitigate against this.11

The summary of product characteristics for Creon, a capsule treatment for PERT, does state that capsules may be opened to release the granules inside and that they can also be taken in this form with acidic fluid or food.12 The powder form can be taken by mouth or via a feeding tube, although asthma-type reactions have occasionally occurred when the powder has been handled.13

The standard starting dose for PERT is 50,000 units with meals and 25,000 units for snacks.14 The main side effects are, ironically, gastrointestinal, with abdominal pain and diarrhoea being commonly reported. However, as the prevalence of each of these in trials was similar to placebo, it has been postulated that the ‘side effects’ are, in fact, symptoms of the underlying disease.11,12

All currently available PERT products are derived from pigs and there are no other options for people with religious or cultural objections to this source.

How PERT works

The capsules or granules are designed to dissolve rapidly and mix with the food as it is being digested in the stomach. As the stomach empties, the PERT enzymes are distributed and released into the small intestine, where the coating on the mini-microspheres containing the enzymes disintegrates, due to the pH value in this area of the body being greater than 5.5, and the enzymes (lipase, amylase and protease) are released. The release of these enzymes then allows fats, starch and proteins to be digested and eventually absorbed.

In trials, the effectiveness of PERT was assessed through something known as the coefficient of fat absorption (CFA). CFA assesses the percentage of fat that is absorbed into the body, while taking into account fat intake and excretion. Trials showed that PERT can improve PEI symptoms such as loose or poorly formed stools, abdominal pain, flatulence and stool frequency by improving fat absorption. Trials also show that outcomes may be improved by using higher doses, using products with an enteric coating, taking treatment during food and supplementing with acid suppression.10

Vitamin D

Low levels of fat soluble vitamins, including vitamin D, may be found in people with PEI. Levels of vitamin D can be tested by measuring serum 25 hydroxyvitamin D levels. If these are low, vitamin D supplementation may be needed.15 However, some commentators suggest that if PERT is titrated successfully, supplementation should not be necessary.16

Lifestyle interventions

Dietician support can be invaluable in helping people to work out the best approach to PEI, especially if they have other conditions such as diabetes or coeliac disease, and to achieve a diet that is varied and nutritious. Foods that are difficult to digest should be avoided. These may include peas, beans and lentils and other high-fibre foods.

Patients with PEI should be supported to stop smoking to minimise its impact on the pancreas. Similarly, if they are drinking more than the recommended amount of alcohol, they should be advised to cut down and, ideally, stop. If the underlying pancreatic pathology is alcohol related they should certainly aim to give up alcohol completely.14,15

THE ROLE OF THE GPN

As previously stated, you should consider the possibility of PEI in people who fall into the ‘at risk’ groups, such diabetes. When patients with a diagnosis of diabetes report gastrointestinal symptoms, these may be considered to be a side effect of metformin or glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP1-RAs). If people find that symptoms do not resolve when these drugs are stopped, or when they switch to modified release metformin, PEI may be the cause.

A thorough history, along with appropriate tests (e.g. blood including Tissue Transglutaminase Antibody [TTG] and vitamin D, and faecal elastase levels) will help to address potential differential diagnoses and identify PEI.15 Faecal calprotectin levels may also be measured as these are elevated in inflammatory bowel disease – an important differential diagnosis.15 If there are no complicating issues, a trial of treatment with PERT may be initiated. However, if there are any features which cause concern or doubt as to the diagnosis, a referral should be made to gastroenterology. Failure to respond should result in a referral to specialist care. In some studies, the addition of a proton pump inhibitor to PERT was found to improve outcomes but there is some debate about this.14

In people with diabetes, initiation of PERT may require adjustments to be made to glucose lowering therapies. The pathophysiology of pancreatogenic diabetes (type 3c) means that most people will require insulin. The potential link between incretin-based therapies and pancreatitis is likely to preclude their use in these patients.17

SUMMARY

PEI occurs when the body lacks the necessary level of digestive enzymes, amylase, protease and lipase, to enable effective digestion and absorption of fats, protein and carbohydrates. This leads to significant gastrointestinal symptoms, malabsorption and malnutrition. PEI is a consequence of several other conditions such as pancreatic disease, cystic fibrosis and surgery. Some people with PEI may have pancreatogenic diabetes (type 3c), however, and this is different from type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

PEI is diagnosed through effective history taking and appropriate investigations, which may include blood tests, stool tests and scans. Management consists of lifestyle interventions (such as diet, smoking and alcohol advice) and PERT. GPNs should be aware that PEI in people with diabetes may be mistaken for drug reactions or complications such as neuropathic problems. It is therefore incumbent on the GPN to have an open mind, and to bear the possibility of PEI in mind when reviewing patients who report gastrointestinal symptoms.

REFERENCES

1. Lankisch PG. Natural course of chronic pancreatitis. Pancreatology 2001; 1: 3–14.

2. Ghaneh P, Neoptolemos JP. Exocrine pancreatic function following pancreatectomy. Annals of the New York Academy of Science 1999; 880:308–18

3. Keller J, Layer P. Human pancreatic exocrine response to nutrients in health and disease. Gut 2005; 54:1–28

4. Olivier AK, Gibson-Corley KN, Meyerholz DK. Animal models of gastrointestinal and liver diseases. Animal models of cystic fibrosis: gastrointestinal, pancreatic, and hepatobiliary disease and pathophysiology. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2015; 308:G459–71.

5. Piciucchi M, Capurso G, Archibugi L, et al. Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in diabetic patients: prevalence, mechanisms, and treatment. Int J Endocrinol 2015:595649

6. Mayor S. Type 3c diabetes associated with pancreatic disease is often misdiagnosed. BMJ 2017; 359:j4923

7. Krishnasamy S, Abell TL. Diabetic gastroparesis: principles and current trends in management. Diabetes Ther 2018; 9(Suppl 1): 1–42. doi:10.1007/s13300-018-0454-9

8. Deprez P, Sempoux C, Van Beers BE, et al. Persistent decreased plasma cholecystokinin levels in celiac patients under gluten-free diet: respective roles of histological changes and nutrient hydrolysis. Regul Pept 2002; 110:55–63.

9. Domínguez-Muñoz JE. Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency: diagnosis and treatment. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 26 (Suppl 2): 12–16

10. de la Iglesia García D, Huang W, Szatmary P, et al. Efficacy of pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy in chronic pancreatitis: systematic review and meta-analysis Gut 2017; 66:1474–1486. https://gut.bmj.com/content/gutjnl/66/8/1354.1.full.pdf

11. Creon Micro Summary of Product Characteristics. Electronic Medicines Compendium, 2016 https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/5564

12. Creon 25000 Summary of Product Characteristics. Electronic Medicines Compendium, 2017 https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1168/smpc)

13. Pancrex V powder Summary of Product Characteristics. Electronic Medicines Compendium, 2017 https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/1056/smpc)

14. Struyvenberg MR, Martin CR, Freedman SD. Practical guide to exocrine pancreatic insufficiency – Breaking the myths. BMC Medicine 2017; 15:29 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5301368/pdf/12916_2017_Article_783.pdf

15. Hambling C, Cummings M, Merriman H , Widdowson J. Pancreatic exocrine insufficiency guideline, 2018 https://www.guidelines.co.uk/diabetes/pancreatic-exocrine-insufficiency-guideline/454173.article

16.TREND-UK. Diabetes and pancreatic exocrine insufficiency. 2018 Available from https://www.dorsethealthcare.nhs.uk/application/files/7215/4358/7864/Diabetes_and_pancreatic_exocrine_insufficiency.pdf

17. Gudipaty L, Rickels MR. Pancreatogenic (Type 3c) Diabetes. Pancreapedia: Exocrine Pancreas Knowledge Base, 2015 DOI: 10.3998/panc.2015.35

Related articles

View all Articles