Mental health in patients with long term conditions

Dr Diana Hutchinson

Dr Diana Hutchinson

Former GP in Coventry, GP trainer

and RCGP examiner

Author

Sheila Hardy

PhD MSc BSc NISP RMN RGN

Senior Research Fellow, Northamptonshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust

Honorary Senior Lecturer, UCL

Postgraduate Nurse Educator, Charlie Waller Memorial Trust

Visiting Fellow, University of Northampton

Contributing editor

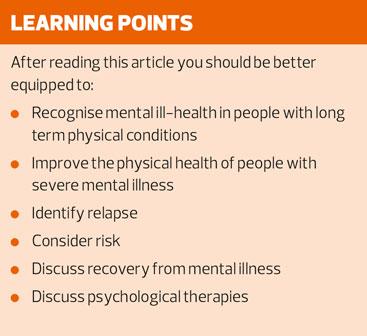

There is a strong correlation between long term physical conditions and mental health conditions, notably anxiety and depression, but a general practice nurse with good communication skills can do much to identify and support affected patients

RECOGNISING MENTAL ILL-HEALTH IN PEOPLE WITH LTCs

A long term physical condition (LTC) can have far-reaching social and emotional implications, affecting independence and relationships, employment and leisure, finances and status.

Many people with long term conditions will develop anxiety, as they face uncertainty and change. There is also a high risk of depression in patients with LTCs, conditions which may themselves cause fatigue, sadness and grief. Some people have strong coping mechanisms but others will develop depression. It is important to recognise depression, as treatment can help considerably.

Here are some factors that make people vulnerable to depression:

- A parent who had depression

- An unhappy childhood

- An inflexible personality

- Social isolation

- Adverse social conditions (worries about money, work, relationships, housing)

A nurse with a warm, non-judgemental attitude can support patients suffering with LTCs and may be able to detect hidden depression. If you have good communication skills, you give your patient permission to talk freely. A nurse reviewing a patient with a long term condition might say ‘Could I please ask you some specific questions, in case you might be suffering from depression?’

We then use the two Whooley questions,1 a blunt tool to screen for depression but better than ignoring mental distress. The questions are as follows:

’During the past month, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless?’

‘During the past month, have you often been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things?’

If a patient answers ‘yes’ to either of the above questions, the ‘help’ question can be asked:2

’Is this something with which you would like help?’

The three possible responses are:2

‘No’,

‘Yes, but not today’

‘Yes’.

Our management is then determined by a holistic assessment of the circumstances.

Similarly, the nurse can use two questions to screen for anxiety:3

‘How often over the last two weeks have you been bothered by feeling nervous, anxious or on edge?’

‘How often over the last two weeks have you been unable to stop or control worrying?’

Patients who may have anxiety or depression need further assessment by a trained clinician, including consideration of risk (see below). If the diagnosis is confirmed, the patient can be offered psychological therapy (talking therapy) and/or medication.

IMPROVING THE PHYSICAL HEALTH OF PEOPLE WITH SEVERE MENTAL ILLNESS

The shocking association between severe mental illness (SMI) and preventable physical diseases must be a priority for all health workers.

People with a severe mental illness (mainly schizophrenia or bipolar disorder) have a life expectancy many years less than other people of the same age. The majority of the early deaths are not due to suicide but are caused by common physical health problems, such as cardiovascular disease and cancer.

People with SMI are much more likely to smoke. They often have poor diet and minimal exercise, associated with lack of motivation, self-neglect, poverty and other social difficulties.

Symptoms of SMI include poor motivation and difficulty with organising and planning. Additionally the medication used to treat the condition may cause sedation. This means that some patients will find it difficult to attend clinic appointments.

The primary care team can help by making appointments for patients (rather than asking them to ring and make one), scheduling appointments for later in the day and sending telephone reminders. We can take a proactive approach to follow-up, calling vulnerable patients if they have missed an appointment.

In common with people with other long term conditions, those with severe mental illness may not adhere to their medication schedule. The reasons include poor insight into their condition (so they don’t think they need treatment) and forgetting medication, due to their illness, or to avoid the side effects. Unfortunately, many anti-psychotic medicines cause weight gain, with the associated risk of diabetes.

What can a practice nurse do? The Lester Resource4 recommends nurse-led interventions from the time of diagnosis, with the motto ‘Don’t just screen – intervene’. Be aware that cardiovascular risk assessment tools (such as QRISK2) may give false reassurance when a patient has severe mental illness. Statins, anti-hypertensives and metformin may be advisable at a younger age than usual.

As soon as SMI is diagnosed, the practice nurse can target cardiovascular risk factors intensively, especially weight gain and smoking. However, you will need to proceed in small steps, one goal at a time, to avoid bombarding the patient with information.

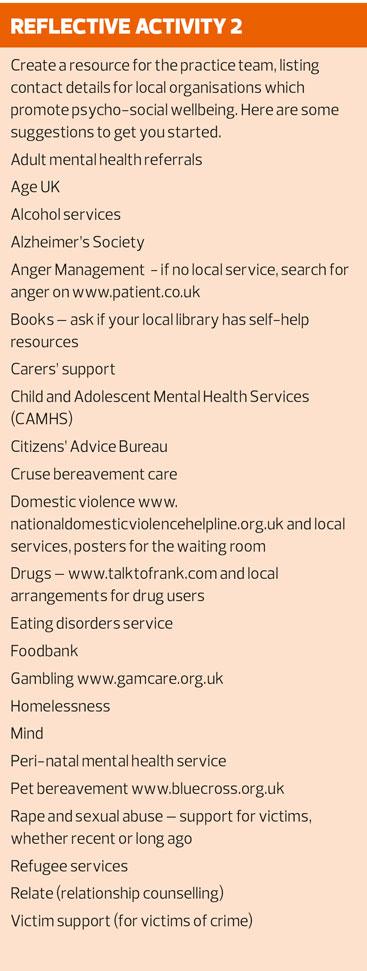

You can encourage exercise (especially walking) and healthy eating. Find out about low cost facilities in your area. For example, does the local leisure centre offer concessionary rates? Where can the cheapest fruit and vegetables be obtained? Ask your patients.

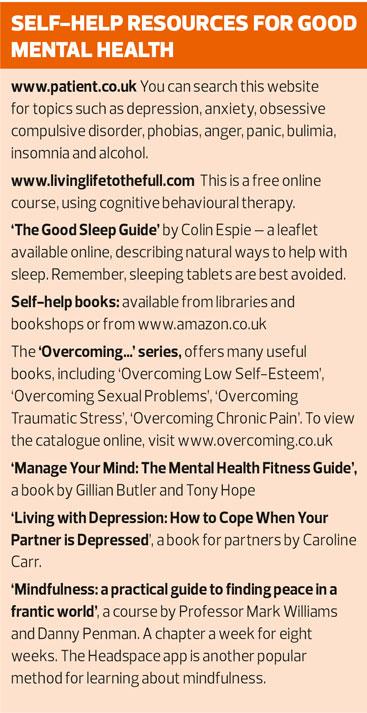

We often hear that people smoke to calm their nerves. People who are addicted to tobacco will experience nicotine withdrawal symptoms if they cannot smoke, a feeling very similar to an anxiety attack. A cigarette (or nicotine replacement therapy) will immediately ease these cravings, but is not a genuine or safe treatment for anxiety. Anxious people will have fewer mood swings if they quit smoking – also more money and better health.

Tobacco increases the metabolism of various psychiatric medicines, so a patient who stops smoking should be carefully monitored. They may need a smaller dose in future. When complete cessation seems impossible, reduced smoking may be a realistic goal.

Patients with mental health problems are at risk from excess alcohol and illicit drugs. It is good practice to enquire, regardless of age or social circumstances, and easy to say ‘We always check…are you using any street drugs?’

As always, the practice nurse should keep an eye on the blood pressure and check that female patients are having regular smear tests.

If a patient has had SMI, you can offer a weight check every time they attend. Weight loss often occurs in self-neglect, profound depression or mania. If weight is rising while a patient is taking anti-psychotic drugs, it may be worthwhile phoning the mental health team to enquire if the medication should be changed.

Lithium is sometimes prescribed as a mood stabiliser, for bipolar disorder or treatment-resistant depression. Lithium has many benefits but needs good kidney function to prevent toxic accumulation of the drug in the body. Long term use of lithium can cause thyroid problems.

Serum lithium levels should be monitored and kept within the therapeutic range, as described in the British National Formulary.5 The blood sample should be taken twelve hours after the last dose of lithium. Kidney function and thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) should also be checked.

IDENTIFYING RELAPSE

Patients with SMI should be taught to recognise their symptoms of relapse and the action they should take if becoming more unwell. This information is generally included in their written care plan. The practice nurse can reinforce the message by asking about their warning signs for relapse. Carers should also have this information.

Psychosis is a disorder of perception and thinking, where the patient may not attribute their symptoms to a mental disorder. When a person with SMI suffers a relapse, they are commonly scared and suspicious. The symptoms can be subtle or they can be very obvious and disturbing to onlookers. A practice nurse can be well placed to help, having established rapport with the service user over months or years. The nurse may notice a change in the person’s emotional state and will know their previous ideas about the illness. There is likely to be mutual respect, enabling the nurse to calm the situation, ensure the patient’s immediate safety and arrange early intervention.

A mental state examination is about your objective observations of the patient, rather than their subjective descriptions of their feelings. It includes the following:

- Appearance – observe cleanliness, clothing, posture and gait

- Behaviour – cooperative or aggressive, calm or agitated

- Speech – speech might be coherent and logical, or perhaps gabbled or loud

- Observed Mood – does the patient appear to you low in mood, apathetic or irritable? Do they seem optimistic or pessimistic?

- Thought – preoccupations, ideas and beliefs

- Perception – hallucinations (which may be auditory, visual, smell, taste, touch)

- Intellect – is the patient orientated in time, place and person? e.g. do they know their current location? [text] Are they functioning intellectually at a level you would expect from their history?

- Insight – how does the patient explain or attribute their symptoms?

In the early stages of psychosis, quite sophisticated interview techniques may be needed to detect thought disorder, delusions and hallucinations. Here are some questions used by psychiatrists:

Do you manage to get out most days? (Apathy is a common symptom of psychosis)

Any special worries? Or distressing thoughts? Do you have any beliefs which other people find unusual or strange?

Do you feel people are looking at you/ talking about you?

Do people know your thoughts? Are your thoughts coming faster?

Have you seen or heard things you cannot account for?

Have you heard voices? (voices discussing/arguing?) Do you receive messages or signals?

In relapse of bipolar disorder, extremes of mood can occur. A person with mania will be hyperactive, with elevated mood and lots of energy. In depression, there is low mood, lack of energy, loss of interest and poor concentration. Sleep disturbance is a cardinal feature of both conditions.

The two most common reasons for relapse of bipolar disorder are failure to take medicines as prescribed and stressful life events. More frequent follow-up is advisable if these situations seem likely. During a relapse, the patient may lack insight but friends and family will notice changed behaviour. You may also notice a difference, if you know the patient well.

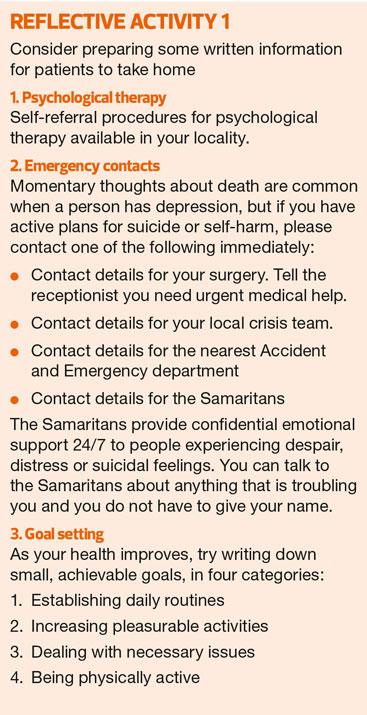

ASSESSMENT OF RISK

Assessment of risk is a necessary part of a psychiatric review, but is a matter of judgement rather than an exact science. We can share our concerns with the patient and the wider healthcare team, as we decide how best to proceed. If children are at risk, you should explain to your patient that you are going to contact Social Services, so that every possible help can be offered to the family.

Vulnerable people are at risk of exploitation by others. Your patient may be at risk from substance abuse, self-neglect, violence, self-harm or suicide. A few patients with mental illness pose a risk to other people, examples being dangerous driving or neglect of their children. Patients with jealous delusions are a particular concern, their partners being at high risk of violence.

Risks of harm are greater if the patient has difficult social circumstances, making them feel isolated or hopeless. Sadly, some of our patients will have faced decades of adversity.

Here are examples of questions we use to assess the risk of suicide, asked in step-wise fashion:

How do you see the future?

Have you ever had thoughts that you cannot go on, that you would like to end it all?

Have you harmed yourself?

Have you made plans to take your own life?

Likewise, you can ask about aggression in a stepwise manner, enquiring first about irritability and anger, then police intervention, fights and violence.

RECOVERY FROM SEVERE MENTAL ILLNESS

Psychiatrists across the English-speaking world are increasingly recognising the concept of recovery from SMI. Anthony6 defined recovery as:

‘…a way of living a satisfying, hopeful and contributing life. Recovery involves the development of new meaning and purpose in one’s life as one grows beyond the catastrophic effects of psychiatric disability.’

Patients with SMI often have complex needs, requiring on-going input from a multi-disciplinary mental health care team. Practice nurses have an important role in the follow-up of such patients, after they have been discharged from secondary care.

A practice nurse is a very suitable person to offer the recovery approach. General practice is a relatively non-stigmatising environment, where we know our families and can offer continuity of care, using respectful, patient-centred consultation techniques. Together, we work towards improvement and recovery. In primary care, we can take a holistic approach, emphasising physical wellbeing as well as mental health.

The nurse should have some knowledge of psychiatric drugs and their side-effects (see the BNF5) but can confidently work with patients to increase their coping skills, reduce dependency and avoid over-medicalisation. It can be useful to find out the person’s mental health needs, which are more important (and individual) than a diagnostic label.

PSYCHOLOGICAL THERAPIES

In a strengths-based approach, we ask the patient what is troubling them the most, then move rapidly to discover what helps them cope. This information is synthesised to help the patient develop a management plan. Empathic statements show you have heard and encourage disclosure, for example, ‘That situation sounds really difficult’.

Another approach is to start a conversation that invites change. You could say ‘What might happen if…’ or ‘Supposing…’ Always remember to be non-directive, because a patient’s response must be based on personal experience and values.

Some patients make arrangements to see a counsellor, which can be useful if there is a specific problem. In a nutshell, a trained counsellor will encourage the client to define their problem and then work with them to set short and long term goals.

Of all the psychological (talking) therapies, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has the best evidence base. In CBT, the therapist works with the client to identify cognitive problems (twisted thinking). These are distorted views of reality, often imprinted at a very young age.

Consider a small child who is ignored and neglected by her family. Years later, suffering depression and low self-esteem, she waves to a friend across the street. The friend is distracted by a window display, so does not respond. The depressed woman feels even worse, thinking she is rejected and worthless.

This distorted thinking leads to changed behaviour. The woman may misinterpret various social situations, stop going out and avoid new friendships. She might perhaps seek solace in alcohol or over-eating. A therapist can help clients unravel these connections and see the world in a more positive light.

Psychological therapies are best started early and we encourage people to self-refer. You need to have leaflets readily available, describing the services in your area. Then you can support your patients through their process of recovery.

REFERENCES

1. Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, Browner WS. Case-finding instruments for depression. Two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med. 1997 Jul;12(7):439–45.

2. Arroll B, Goodyear-Smith F, Kerse N, Fishman T, Gunn J. Effect of the addition of a “help” question to two screening questions on specificity for diagnosis of depression in general practice: diagnostic validity study. BMJ. 2005 Oct 15;331(7521):884

3. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Monahan PO, Löwe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Mar 6;146(5):317–25.

4. The Lester Cardiometabolic Health Resource [Internet]. [cited 29th October 2015]. Available from www.rcpsych.ac.uk/quality/NAS/resources

5. British National Formulary. Available from: www.evidence.nhs.uk/formulary/bnf/current/4-central-nervous-system/42-drugs-used-in-psychoses-and-related-disorders/423-drugs-used-for-mania-and-hypomania/lithium/lithium-carbonate

6. Anthony WA. A recovery-oriented service system: Setting some system level standards. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal. 2000;24(2):159.

Related articles

View all Articles