Care and support planning: A new approach for patients with long term conditions

Lindsay Oliver

Lindsay Oliver

BSc (Hon)

National Director, Year of Care Partnerships, Northumbria Healthcare Trust, Northumberland

Sue Roberts

MSc FRCP FRCGP(Hon)

Chair, Year of Care Partnerships, Northumbria Healthcare Trust, Northumberland

Rebecca Haines

MBChB MRCGP, GP

Glenpark Medical Practice, Gateshead and Clinical GP lead with the Year of Care Partnerships, Northumbria Healthcare Trust, Northumberland

There are dilemmas and challenges when introducing and learning about new ways of working, not least whether the name ‘care and support planning’ adequately describes this approach to the management of patients with long term conditions or complex needs

Does it matter how we name the components of health care as long they are functionally effective and are of high quality? Our work1 supporting teams to introduce ‘care and support planning’ (CSP) as routine for people living with one or more long term conditions (LTCs) suggests that it does.

We know the term CSP means different things to health care professionals from different backgrounds. It is often confused with ‘treatment planning’ and this can have a significant negative effect on the chances of introducing and sustaining it successfully in practice.

We hypothesised that the use of ‘provider’ or ‘professional’ language by practice teams might be an equally important barrier to involving people who use the services and in providing meaningful feedback for improvement.

This article describes our learning about language during a local feedback project to find out what service users felt was important about CSP, if it was happening in practice and to guide improvement.

WHAT IS CARE AND SUPPORT PLANNING?

Care and support planning (CSP) is a new way of providing routine care in general practice for people living with single or multiple LTCs or complex situations such as frailty. It replaces the traditional ‘tick box’ annual review driven by QOF.2 It is a core component of the initiative to promote person-centred care in the NHS Long term plan,3,4 and from April 2021 will be introduced as part of the national incentive schemes for Primary Care Networks.

People who live with long term conditions (LTCs) make the majority of decisions that affect their lives, but currently spend relatively little time discussing their condition(s) with healthcare practitioners. CSP seeks to transform these brief encounters into meaningful and useful ’conversations’, which are enabled by ‘preparation’ and focus on looking forward and planning. The aim is a single conversation, however many conditions or issues the person lives with, and includes links to supportive activities in the wider community (social prescribing).

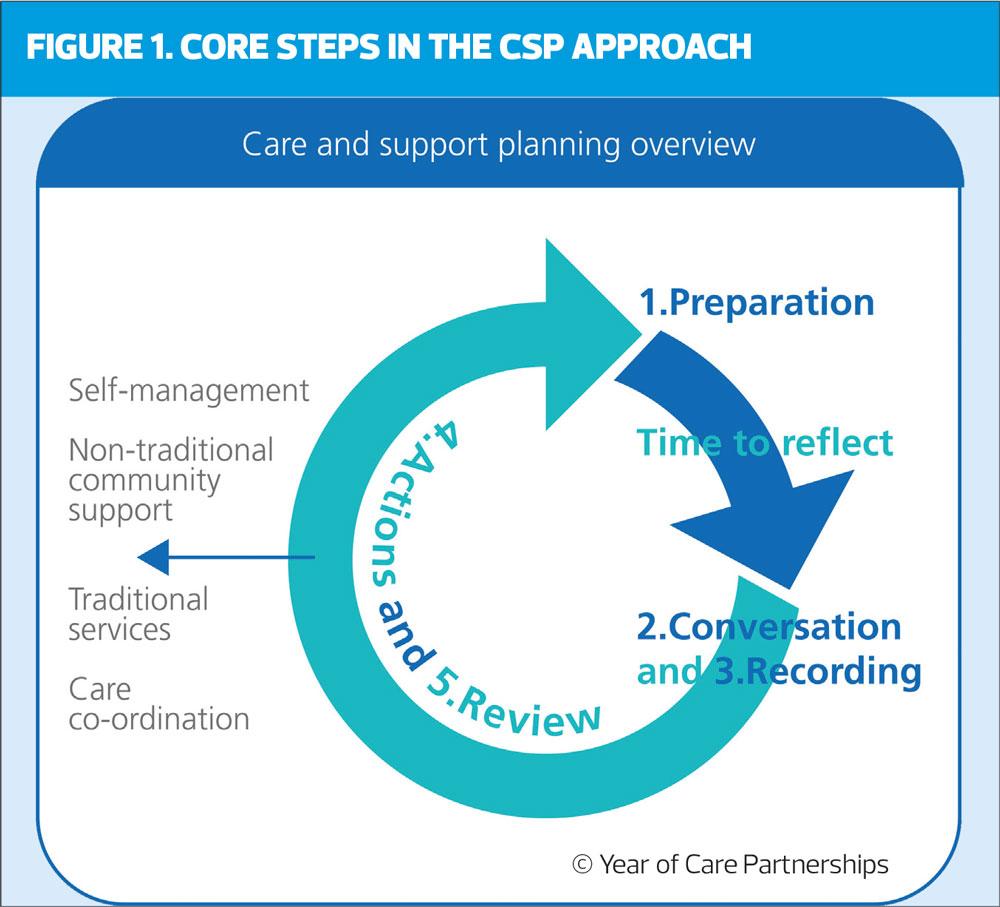

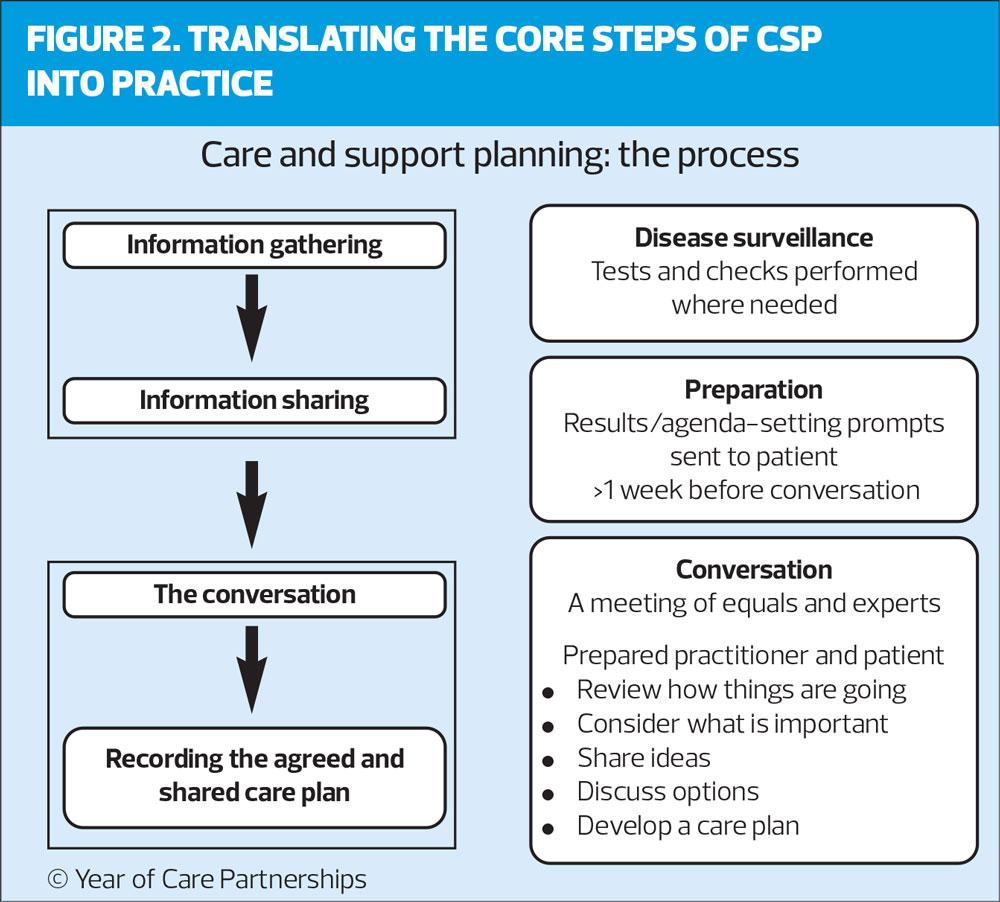

Introducing CSP involves a significant amount of work ‘behind the scenes’ within the practice involving a change in perspective for healthcare professionals, adaptation and development of new skills and introducing practice pathways to ensure the five core steps are linked together and the new ethos is clear to each patient. Figure 1 demonstrates how the components are laid out.

From the individual’s perspective, the first change is a new ‘preparation’ step (figure 2). Relevant tests are performed and assessments made in an initial information-gathering appointment with a healthcare assistant (HCA). Each person then receives the results and personalised information together with reflective prompts 1-2 weeks before a second appointment with a trained practitioner when their CSP ‘conversation’ itself takes place. The practice informs each person ahead of the change and the HCA explains the next steps to them.

Following a pilot project, Newcastle and Gateshead CCG used an incentive scheme to introduce CSP as normal care for those living with QOF conditions.5 Most practices (59 out of 63) are now involved,6 and both individual practice teams and the CCG wanted to involve service users in ensuring that quality is maintained, and improvements incorporated long term. The first step was to listen to the experience of local people involved in CSP and what they thought was important.

THE STUDY

Glenpark Medical Practice was an early adopter of CSP for diabetes and other QOF conditions. Members of the Practice Champions’ group and the Gateshead Long Term Condition Patient group were brought together in two focus group sessions a month apart. The purpose was to explore with the group how we might go about framing questions for evaluation and feedback of care and support planning. In total 25 people who lived with a long term condition, most of whom had experienced CSP, took part. The sessions were led by an experienced facilitator.

Participants were asked a series of questions which they discussed in pairs and fed back in small groups with the aims of:

- Identifying the language that people who had experienced CSP used to describe it as an initial step to support meaningful feedback

- Discovering what participants saw as different about CSP from previous experiences of care (in this case their usual disease-specific annual reviews)

- Discovering what impact they recognised and thought important

- Gathering their suggestions to support feedback

The themes, ideas and dilemmas that emerged were collated and fed into local discussions and the wider learning presented here.

Care and support planning – the language

Although 70% of participants had experienced CSP, nobody recognised the words ‘care and support planning’ until the component parts were drawn out and described step-by-step. This was not a straightforward process. Participants had to engage with the rationale for the changes, recognise the practical steps and then reflect on their own experiences. At this point, the group became involved enthusiastically.

A multitude of suggestions were made about what the process should be called. Participants found it easier to give names to the separate steps in the process rather than the overall intervention. They also reflected that they hadn’t been clear about the name because of inconsistencies in the correspondence and words used by different practice team members for the various elements. They concluded that a consistent approach, with staff and patients recognising the linked components was vital both within and across practices in an area if people living with LTCs were going to engage with it in a meaningful way. The phrase ‘Care and Support Planning’ was initially felt to be cumbersome but following discussion, which included an attempt to find acronyms, the group decided that the words themselves(‘care’, ‘support’, ‘planning’) were easy to understand and reflected their experience.

KEY ISSUES FOR SERVICE USERS

Once the group had orientated itself to the process, those that had experience of it were able to describe some of the differences that made it stand out from previous/usual care. These fell into three groups: how things are organised, the value of being prepared and the nature of the CSP conversation with different people valuing different aspects.

How things are organised

Participants reflected on how it felt to live with a LTC and be recalled by the GP practice for an appointment: ‘The word “appointment” makes your heart sink’. The group felt that CSP was different and ‘like more of an invitation’.

Many of the participants had a number of long-term conditions and liked the way CSP was coordinated to bring all an individual’s health conditions together. One participant noted that the new way of working ’Cuts the number of appointments down…my son was always saying – you’re always at the doctors’ dad… now I can plan to go away without missing appointments’. The group also liked the birthday recall, which made it easier to remember.

The value of being prepared

The preparation step includes an information-gathering appointment (if there are tests and tasks to complete), sharing the results with the person together with relevant information and agenda-setting prompts, and time to reflect ahead of the CSP conversations.

The group compared this favourably with the previous way of working. ‘Getting results sent is so much better than being told “no action necessary”’; ‘Before you had the normal MOT tests but then you don’t hear anything. If you phone, they’d say no action necessary but this way you can see them.’

In particular, people valued having the information written down. They said ‘at least I can see it and compare’ and they ‘liked the fact that the record was very straightforward so I could understand it – it was in layman’s terms’. It seemed important to show trends: ‘You get “stuff” beforehand [from the practice] to compare “before” and “now” ’.

Much of the value seemed to be about the opportunity to raise issues and have time to reflect before the CSP conversation. ‘You have more time to think’; ‘You can write down your concerns’. For some people the preparation prompt made it much easier to bring up difficult issues at the subsequent CSP conversation: ‘Able to write things down which are difficult to say’; ‘ I could just slide it in over the table without having to say it’; ‘You’ve already written [what you are concerned about] down’.

The nature of the CSP conversation

CSP conversations bring together and value the expertise and experience of both the person living with LTC(s) and the healthcare professional. The aim is to focus on planning care with the person, based on what is important to them, including identifying their own goals and ideas of how they can achieve them. Workshop participants reported that this new way of working ‘felt more relaxed with time to talk’. One person attributed this to the manner of the clinician ‘the way she was talking [felt] comfortable’.

They also valued that the CSP conversation wasn’t focused on a single disease or condition: ‘It can have everything included – not just diabetes. For example, I have angina. It can be anything concerning you or worrying you’. Another individual said: ‘It pulls everything together so you`re not going to different [appointments] and can speak about anything you`re concerned about. You get more time than you used to have. You have already written down what your concerns are’.

For some people the way in which the conversations were delivered meant they could openly discuss difficult issues: ‘It doesn’t necessarily have to be about what is wrong with you – it can be anything concerning you’ and for one person this had been an opportunity to talk about significant issues: ‘You are able to discuss things you normally wouldn’t be able to discuss like personal, sensitive things you haven’t talked about for years – so it opens things up and you are able to do this as it felt a more relaxed approach, not rushed’.

Not only was the discussion easy to take part in – ‘it was straight forward – even I could understand, and I don’t always understand’, it was also useful in thinking through ideas and ways to manage their long term conditions: ‘You talk about areas where your health could be improved and get some ideas as to what might help’. One person summarised this as being ‘A lot more about me, with time to think’.

Other findings

It gradually emerged that although some workshop participants had not been involved in CSP they were under the impression that they had been. It was not until they saw the detail of the process and listened to the experience of others that they realised they were not experiencing CSP themselves.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PEOPLE LIVING WITH LTCs

CSP processes and conversations were highly valued by people with long term conditions once they had experienced this way of receiving routine care, reflecting the findings in other health communities.7 Those who weren’t receiving CSP were keen to see it happen.

The workshops demonstrated that even people who had experienced CSP were not familiar with the term ‘care and support planning’ and didn’t easily recognise the whole process and links between the component parts. There was consensus that this was important if people were to understand what to expect, their role and how they could gain the maximum benefit. It was also essential if they were to be part of assessing if the practice were delivering CSP consistently to a high standard. They recommended that the process was consistently called ‘Care and Support Planning’ across the locality to increase familiarity and aid involvement.

Workshop participants hoped there could be more active ‘marketing’ wherever CSP was introduced, to raise awareness among people living with LTCs about its availability and actively support people to understand how it differed from their usual care. Suggestions included using social media, local press, local champions, and presentations at patient meetings and group education sessions, as well as traditional approaches such as practice materials, websites, posters in the waiting area, and information on waiting room TV screens. Patient groups themselves might be best placed to design publicity materials, as well as offering feedback to practices on how they were doing.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICES

These observations have important implications for practice teams introducing CSP or indeed any new way of working. As well as introducing the CSP steps and orientating patients to this, practices need a systematic approach to raise awareness of these issues, including the consistent use of language, among all the practice staff whether or not they are directly involved. This must be built in right from the start.

The workshops recommended that practices should:

- Consistently call the new way of working ‘Care and Support Planning’

- Ensure staff and patients know what is different about the philosophy, care processes and care planning conversation

- Ensure staff and patients know what it is replacing and why it could be beneficial

- Harness the positive experiences of those who have received CSP to inform and support other people new to the process

IMPLICATIONS FOR RESEARCHERS, EVALUATORS AND POLICY-MAKERS

This small project was devised as the first step in a local approach to garnering feedback about CSP. As well as providing local learning it raised important challenges for researchers, evaluators and policy-makers more widely.

Without common terminology, an agreed definition of CSP, an understanding of the multistep process and what each component involves, neither the study researcher nor the patient can have a congruent conversation or complete and analyse questionnaires meaningfully. The first step in any evaluation is thus to recognise this challenge and take active steps as part of the study design to ensure that patient participants and researchers themselves both understand the CSP intervention and how it is described and delivered locally. The learning from these workshops is that explanatory material, whether delivered verbally or written, may not be enough without a process of built-in sense-checking.

Some of the common pitfalls when gathering information include:

- People who have not experienced CSP being included in focus groups or evaluations designed for those that have

- People who have experienced CSP finding it difficult to distil the components of CSP from other appointments or aspects of their health care when providing feedback

- Obtaining feedback (e.g. questionnaire or technology/ text responses) at some time interval from the CSP process leading to confusion with ‘last appointment’, ‘recent appointment’

- Using standard questionnaires with different terminology

- Confusing the ‘information gathering appointment’ with the CSP ‘conversation’ because of local terms and failure to probe understanding.

Participants in this study also had clear views about what they valued about CSP. Traditionally the number of care plans has been counted as a proxy for person-centred care,8 although these often reflect a provider ‘treatment’ agenda. For most people in these workshops, a care plan was just a bi-product of the conversation. Most did not identify strongly with the plan itself but were very positive about a single holistic CSP process. They valued the two key components of the approach: preparation, and a better conversation focused on what is most important to the person. Future evaluations would benefit from ensuring these components are in place and being delivered to a high standard rather than counting care plans alone.

CONCLUSION

Although CSP has been subject to many years of observation, evaluation and modification in numerous sites, these small facilitated workshops which focussed entirely on understanding how people with LTCs themselves experience, understand and value CSP, have provided additional insights that have lessons beyond the local learning. They highlight the importance of using clear terminology and consistent approaches to describe new ways of working, so that practice teams and patients alike can understand and be familiar with the approach they are either delivering or receiving. Evaluations and feedback should include those aspects which patients’ value most highly and be carried out by those who are familiar with them.

REFERENCES

1. NHS. Year of care partnerships. https://www.yearofcare.co.uk

2. Bryant L, Oliver L. Year of Care – planning together for effective care. Practice Nurse 2016;46(03):36-40

3. NHS England. Universal Personalised Care: Implementing the Comprehensive Model. https://www.england.nhs.uk/personalisedcare/upc/comprehensive-model/.

4. NHS England. NHS long term plan. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/.

5. Gateshead British Heart Foundation House of Care Report. https://www.yearofcare.co.uk/sites/default/files/pdfs/item6_i_Gatehsead%20BHF%20House%20of%20Care%20Evaluation%20Report.pdf.

6. Chapman S, Cooper R, Haines R, et al. Redesigning general practice around care for long term conditions and multi-morbidity. https://www.yearofcare.co.uk/sites/default/files/pdfs/Year%20of%20Care%20poster%20A1%20FINAL.pdf.

7. Roberts S, Eaton S, Finch T, et al. The Year of Care approach: developing a model and delivery programme for care and support planning in long term conditions within general practice. BMC Fam Pract 2019;20:153 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-019-1042-4

8. GP Patient Survey. https://www.gp-patient.co.uk/.