Anticipatory care: management of long term conditions in primary care

Kirsteen Marie Coady, BA,QN

Kirsteen Marie Coady, BA,QN

Nurse consultant, NHS Grampian House of care trainer, NHS Education for Scotland Advisor and Supervisor for General Practice Nurses

Practice Nurse 2022;52(4):14-18

General practice plays a crucial role in the evidenced-based management of long term conditions, with the general practice nurse (GPN) being the linchpin in managing and shaping care delivery

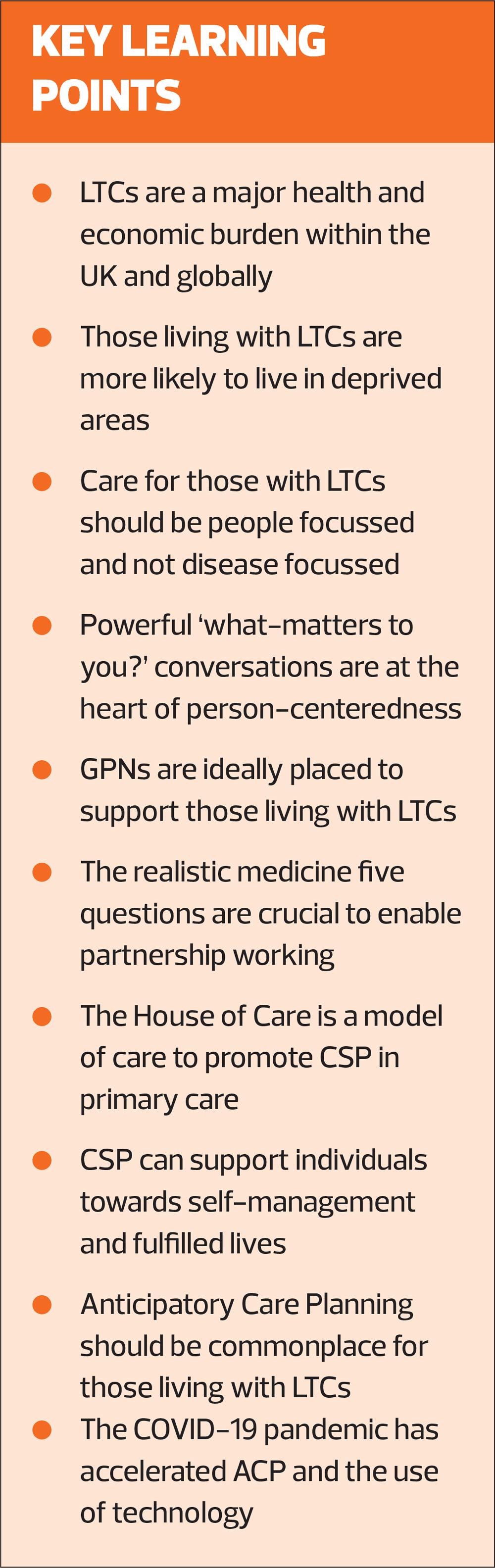

Long term conditions (LTCs) are the most common reason for death and disability within populations worldwide and represent the greatest challenge facing health care systems as they endeavour to prevent early mortality and disability. LTCs represent illnesses whose pathology demonstrates slow progression and are therefore chronic in nature. The Department of Health defines an LTC as: a condition that cannot, at present, be cured but is controlled by medication and/or other treatment/therapies.1

LTCs are recognised as enduring non-communicable conditions, which require ongoing medical care such as: diabetes, cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma and dementia. While these conditions represent the UK’s clinical priorities, LTCs also include a wide range of conditions and disabilities, such as coeliac disease, arthritis, some cancers as well as physical and learning disabilities. Many individuals are living with more than one, resulting in multimorbidity. While this adds to the complexity of care planning, the healthcare needs faced by individuals living with LTCs cannot be overstated, as they endeavour to cope with issues that include symptoms management, medication regimes, accessing social care support, a sense of loss in health status and the impact on personal and family relationships.

The expertise and unique focus of the GPN in managing care and supporting individuals with LTCs is widely recognised as an intrinsic part of this professional role.2 This necessitates a critical understanding of person-centred approaches and the application of service delivery models that embrace collaboration, cooperation and enhanced communication with providers, professionals and individuals. A central tenet of LTCs management is anticipatory care, which seeks to pre-empt the potential for health problems emerging or to prevent further deterioration in health status. More specifically, managing LTC care demands a wide skill set to continuously improve the information, support, care and treatment of people living LTCs, which will include:

- Assessment and consultation skills

- Health promotion

- Self-management

- Empowering individuals to be more actively involved in their own care,

- Integrated care approaches

- Shared decision-making and care planning

- Partnership working

- Networking with third sector/voluntary/community groups

More recent iterations of the GMS contract, for example, 2018 in Scotland and 2019 in England, continue to place a high priority in effectively managing LTCs, endorsing the crucial role of general practice and the contribution of the GPN and the wider primary care team.

PREVALENCE, DEMOGRAPHICS AND HEALTH CARE BURDEN

The UK population is ageing, life expectancy has increased and mortality rates have declined, and although applauded, this correlates with the risk of living with an LTC /multiple LTCs and an increased need for future care.3 Around 26 million people in the UK live with at least one long-term condition with 10 million of those with two or more. The social impact having a LTC indicates that only 59% of people with LTCs are in employed work in comparison to 72% general population

Higher mortality rates for those with LTCs as well as stagnation of life expectancy occur in more deprived areas and demonstrate disparities across differing communities.4 In 2012, individuals in the poorest social class (class V) had a 60% higher prevalence of LTCs than those in the richest social class (class I) and 30% of people living with poverty experienced greater severity of disease.5 LTCs accounted for about 50% of all GP appointments, 64% of all outpatient appointments and over 70% of all inpatient bed days.5 By 2035, the number of those aged over 85 are projected to double that of the previous two decades with the majority of people living with four or more LTCs.6

HEALTH INEQUALITIES

Health inequalities represent the unjust preventable differences in people’s health across the population and between specific population groups, particularly for those living in the most deprived communities.7 There is well documented evidence that individuals suffering health inequalities are at higher risk of developing LTCs, including multimorbidity, which occur at least 10-15 years earlier and with greater severity compared with those living in the most affluent communities.8

Long-term conditions also can adversely the individual’s social perceptions of self, affecting their quality of life and lead to further inequality. The impact of living with a LTC reflects an increased risk in developing anxiety and depressive illnesses that adversely affects the underlying illness and mental health status, leading to poorer outcomes, a risk which often remains unrecognised.9

NHS England’s Improving access for all: reducing inequalities in access to general practice service10 is a key resource which can support GPNs in working towards maximising equality so those who need care receive the right care, at the right place, right time by the right person.

HEALTH SCREENING AND SURVEILLANCE

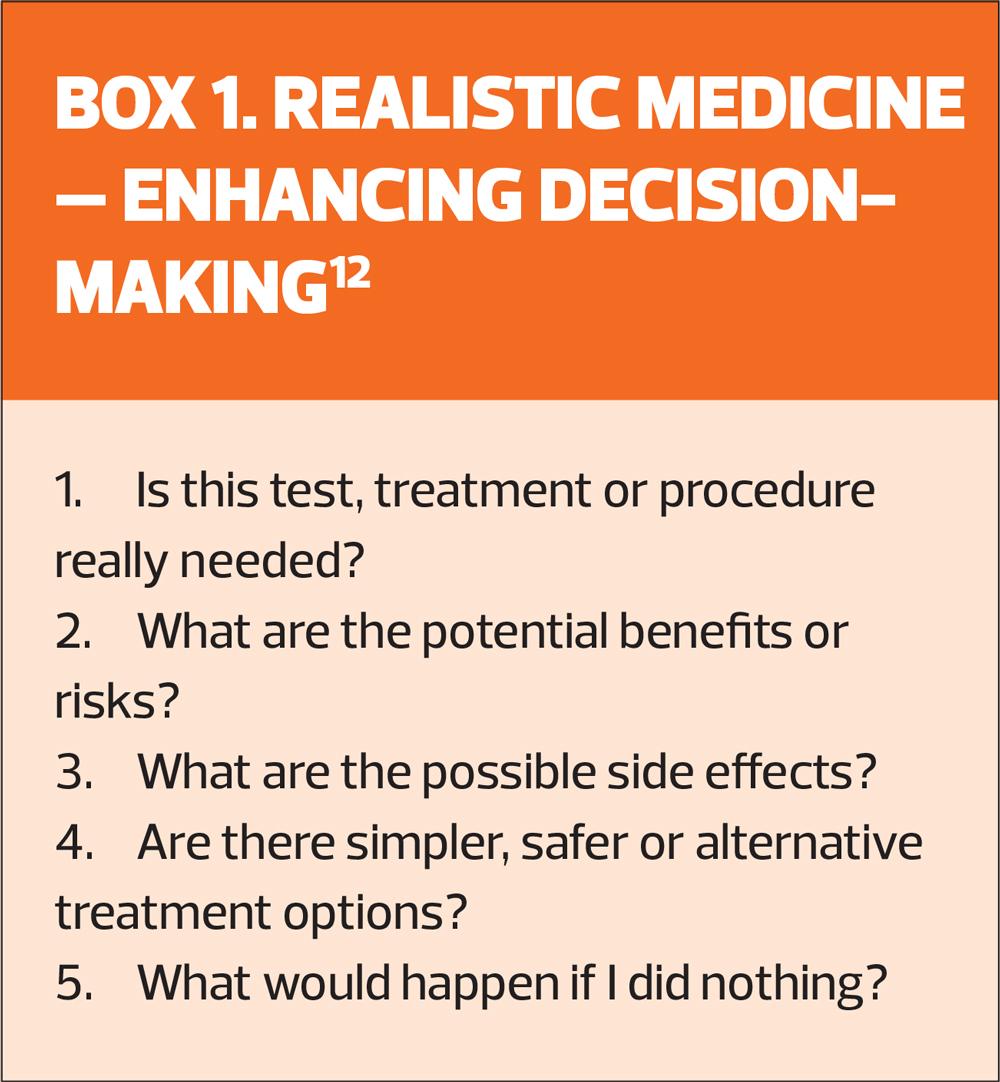

Health screening and surveillance are fundamental public health components of the GPN’s role with the aim of early detection of disease and prevention of complications of existing disease. Despite the current variances in the operation of the QOF across the UK, it does provide a framework for health screening and surveillance within General Practice. The QOF entails disease-focused management, which may arguably lead to ‘disabling’ rather than ‘enabling’ individuals and may inhibit the opportunity to explore what really matters to people living with LTCs.11 Furthermore, with routine LTC review consultations focusing on the assessment of biomedical markers, the healthcare professional undeniably assumes the role of ‘expert’; this may add to the treatment burden with the individual becoming overwhelmed, their agenda unheard and feeling unable to confidently participate in shared decision-making about their health.9 Practitioners experience the LTC consultation as perfunctory disease surveillance and the QOF agenda and protocols as unresponsive in identifying unmet needs.9 Practising Realistic Medicine12 provides direction for the application of person-centred care that places the individual at the centre of shared decision-making. The ethos of ‘realistic medicine’ is about exploring the individual’s preferences regarding what is most important to them and developing a shared understanding of how healthcare might realistically contribute to this using open, authentic and meaningful conversations. Providing a good experience of care provided for people living with LTCs is a fundamental aspect of Practising Realistic Medicine. Box 1 summarises five crucial questions that GPNs and other care professionals should consider using to enhance decision-making.

Indeed, individuals with LTCs can be encouraged to ask these questions themselves to help make informed choices within a partnership approach with a health care professional.

In the general practice setting, this approach could assist the individual with hypertension to decide whether or not to opt for statin treatment for primary prevention, and aids shared-decision making.

PERSON-CENTRED MODELS OF CARE FOR LTCs

The cornerstone of LTCs care is the provision of person-centred care, where the emphasis is placed on ‘who’ the person is, rather than ‘what disease or condition’ they are presenting with. This perspective challenges traditional paternalistic top-down approaches to managing consultations that place an overt focus on biomedical markers by health professionals adopting ‘expert’ positions.9 Person-centred care supports people to develop the knowledge, skills and confidence to manage their conditions and importantly give voice to their agenda to make informed choices about their own health.13 The term, person-centred, is more appropriate rather than patient-centred as the emphasis is on an individual person and not a focus on disease. The four principles of person-centred care are that care is:

- Personalised

- Coordinated

- Enabling, and

- Each person is treated with dignity, compassion and respect.13

Consultation styles, which solely focus on discussing disease or condition, can alienate the unprepared individual and what matters to them within their lives in living with the condition. The ‘What matters to you?’ health improvement initiative,14 encourages more meaningful conversations between health care professionals and those they care for. The initiative’s mantra of ‘ask what matters, listen to what matters and do what matters’ promotes safe, effective person-centred care.

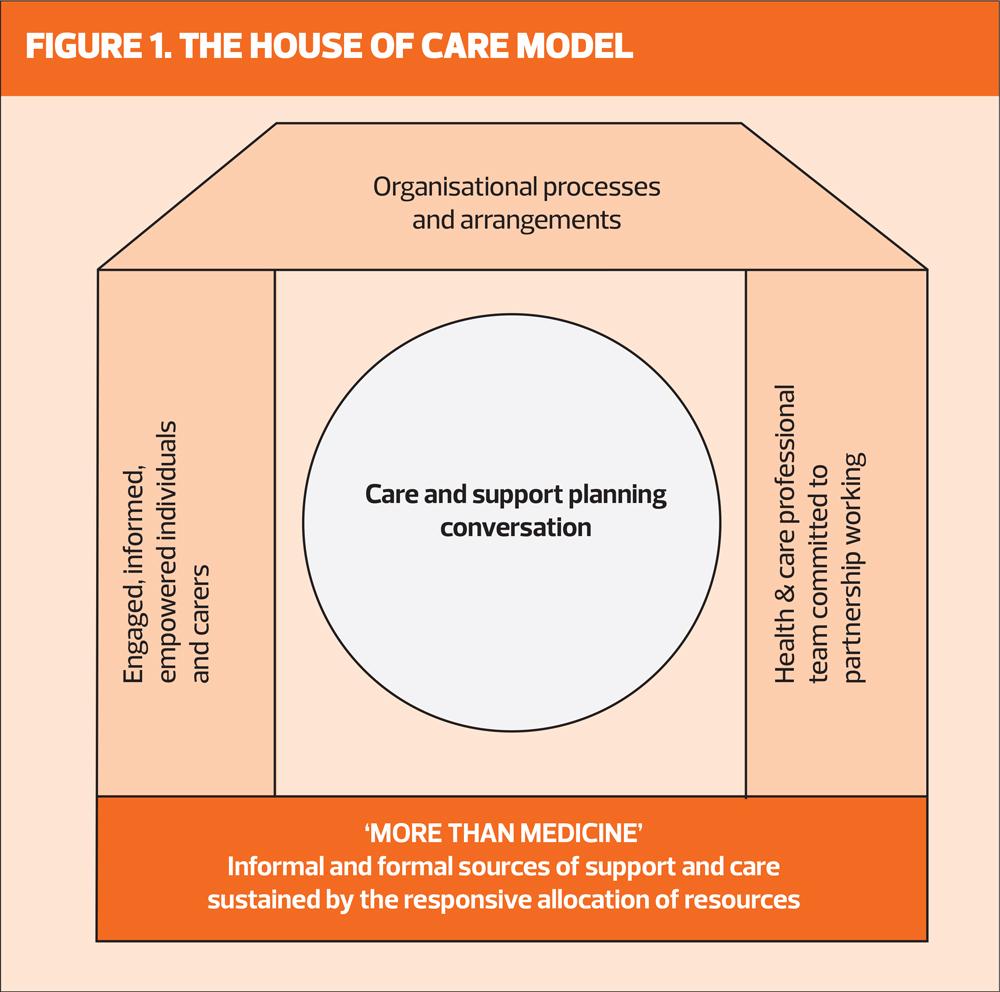

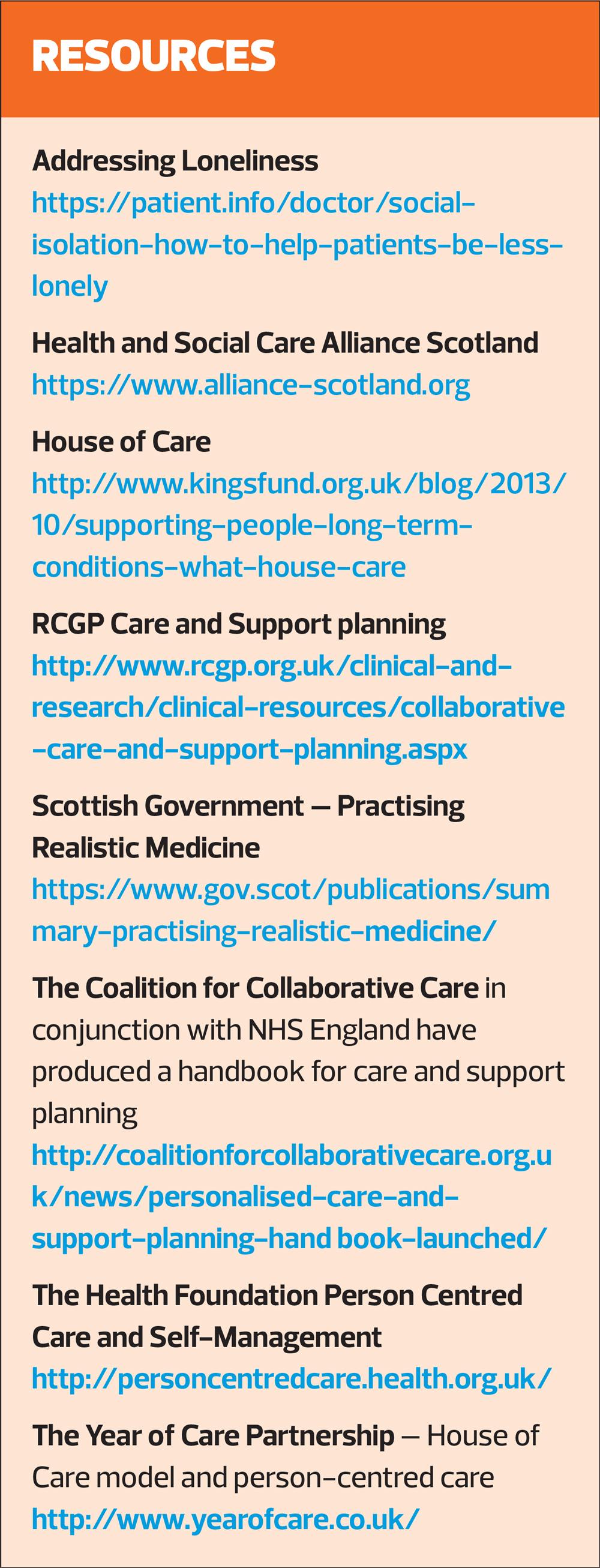

The structuring of care for LTC management has over the decades shifted from a biomedical model to person-centred anticipatory approaches. One such model, which has gained prominence, is the House of Care which is a person-centred, powerful model capable of contributing to supporting individuals to self-manage LTCs in community settings. It was developed by the ‘Year of Care’ partnership, originally for a diabetes programme in England, and was specifically adapted for UK primary care settings to pave the way for collaborative relationships to help people self-manage their LTCs.15,16 It uses the metaphor of a house and centres on individuals as the focal point rather than their specific disease, and embodies the philosophy of being ‘more than medicine’ and truly embraces person-centeredness. The house metaphor (Figure 1) delineates a whole systems approach with interdependency between the structural components of the ‘house’, which need to be in place and functional in order to support each other in co-ordinating the care for those with LTCs. The interdependent structures are crucial to the House of Care’s stability; a weakness in one area could result in the metaphorical collapsing of the house, which in practical terms, could lead to ineffective care.

Key elements of the House of Care model are:

- People with LTCs feel engaged in decisions about their treatment and to be able to act on these decisions

- Professionals committed to working in partnership with patients

- Systems in place to organise resources effectively

- A whole system approach to commissioning health and care services

Whilst the clinical monitoring of LTCs are crucial aspects of care management, such as the serological monitoring for particular diseases, the House of Care model also encompasses psychological health and social care. Use of a holistic model seeks to empower individuals who can manage their conditions with improved emotional, physical and mental health.7 The model can also promote equality within consultations as individuals registered at the practice receive their test results prior to attending a protected appointment for a meaningful ‘care and support planning’ (CSP) consultation/ conversation.

‘Care and Support Planning’ reflects a structured process whereby individuals set their own aims and goals to address their concerns. CSP represents a viable forum that supports a balance of agendas and partnership approaches leading to formulating a person-led, as opposed to nurse-led, care planning. CSP is structured around SMART objectives (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic and Time bound) to respond to individual’s needs and explore their perception, readiness and confidence towards change.

The impact of CSP conversations can help change the lives of others if they are person-focussed rather than disease orientated or dominated by a nursing/ medical agenda. GPNs are perfectly placed within primary care to demonstrate professionalism in partnership working to enhance CSP conversations whether via face-to-face, video consultation or telephone. GPNs are also in a prime position to help identify a multitude of problems which often arise in the context of living with a LTC, such as uncovering social isolation, and networking with services/ agencies that may help support individuals (such as third sector services).

CSP aligns with other strategies, such as ‘Making every contact count’ (MECC) if the focus is on the individual themselves and their needs. MECC is an evidence-based approach to improve health and wellbeing17 which has significant affinity with LTC management that can be used in tandem with CSP. However, the key concerns in exploring what really matters to people may be multi-factorial and CSP conversations are person-led, but if lifestyle change is what really matters then MECC is an appropriate strategy. A key consideration at this juncture is that what really matters to individuals may not directly align with their LTC, and in this context third sector agencies may able to bridge the gap in meeting needs and enabling individuals. The GPN has a fundamental role in signposting those in their care to voluntary sector agencies, which may help them to achieve their full potential or help meet an unmet need.

ANTICIPATORY CARE PLANNING

Taking the time to listen and have a truly shared conversation is invaluable aspect of shared-decision making, which lies at the heart of CSP. However, this process may be impeded by those suffering social isolation, which although more common in the elderly, does affect younger adults and children. Reduced social contact and feelings of loneliness are associated side effects of living with a LTC, for example, having a chronic and debilitating dermatological condition, such as psoriasis, induces a reduced quality of life. GPNs are in a unique position to identify people who may be at particular risk of social isolation and this include consideration of impact of COVID-19 and the necessary escalation in social distancing, self-isolation and shielding for individuals with LTCs who maybe at higher clinical risk.

Anticipatory care planning can be a powerful tool for facilitating ‘thinking ahead’ conversations with individuals and if conducted in a person-centred manner this can help individuals and carers set personal goals to ensure that the right thing is done at the right time by the right person, ultimately leading to the right outcome so that personal choices are heeded.18 Anticipatory care ‘thinking ahead’ ideology is supported by a Key Information Summary (KIS) that contains accurate information about the individual and been found to reduce the risk of hospital admission by 30-50%.18 A person-centred app, ‘Let’s Think Ahead’, has been developed to support anticipatory care planning and can be recommended to those living with LTCs, where appropriate, and who have access to smart technology.

Anticipatory care planning should not be a strategy reserved for individuals facing end-of-life care or overtly complex health needs but can be used for anyone who could potentially benefit; including those living with multiple LTCs. The evidence suggests early intervention of anticipatory care planning can, irrespective of age, optimise health outcomes, improve the quality of life and contribute to appropriate care provision.18 Anticipatory care planning and the formation of a KIS in a person’s primary care record should be seen as a powerful tool to optimise care. The aim of anticipatory care planning is to address individual needs while simultaneously increasing safety netting by sharing information between primary and secondary care and reducing unnecessary hospital admissions. The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic has hastened the formation of the KIS and anticipatory care planning by health care professionals. Arguably, the complex change processes triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic promoted the implementation of anticipatory care planning principles.

SUMMARY

The management of LTCs is complex and involves partnership working within a culture of person-centeredness. In essence, individuals with LTCs are reliant upon care driven by service providers and this chapter has focussed on the need for care to be structured in a person-centred manner and health inequalities should be addressed to maximise health care provision.

The House of Care model, which incorporates CSP, has been identified as model of care, which paves the way for person-centeredness, and equality within consultations and GPNs are in a privileged position to establish what really matters to people. The challenge is to provide people focussed care rather than disease focussed care. Person-centred conversations have the power to lead to self-managing populations; individuals living their lives to the best then can. Third sector organisations are central to helping individuals with LTCs to live more fulfilled lives if underlying needs are met.

The global pandemic of COVID-19 has impacted upon the management of LTCs and has driven forward the use of technology and anticipatory care planning. Anticipatory care planning can ensure needs are met and individual wishes be known at all stages of living with an LTC. The challenge for policy makers and professionals alike is to collaborate and share in decision-making to ensure that the values of those living with LTC bring about a self-managing, more fulfilled population. The challenge lies within.

REFERENCES

1. Department of Health. Liberating the NHS: No decision about me, without me; 2012. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/216980/Liberating-the-NHS-No-decision-about-me-without-me-Government-response.pdf

2. Chowdhury S, Stephen C, McInnes S, Halcomb E. Nurse-led interventions to manage hypertension in general practice nursing: A systematic review protocol, Collegian 2020;27;340-343

3. Office for National Statistics. Overview of the UK population: August 2019. https://www.ons.gov.uk/releases/overviewoftheukpopulationjuly2019

4. Public Health England. A review of recent trends in mortality in England; 2018. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/827518/Recent_trends_in_mortality_in_England.pdf

5. Department of Health. Long-term conditions compendium of Information: 3rd edition; 2012

6. Kingston A, Robison L, Booth H, et al. Projections of multi-morbidity in the older population in England to 2015: estimates from the population Ageing and Care Simulation (PACSim) model. Age and Ageing 2018;47(3):374-380

7. Williams E, Buck D, Babaloa G. What are health inequalities? 2020. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/what-are-health-inequalities?gclid=EAIaIQobChMIxa6_8L7e6gIVQuvtCh1j7g0yEAAYASAAEgJ3rfD_BwE

8. The Health Foundation. Health equity in England: the Marmot review 10 years on; 2020. https://www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/the-marmot-review-10-years-on

9. Chew-Graham C, Sartorius N, Cimino LC, Gask L. Diabetes and depression in general practice: meeting the challenge of managing comorbidity. Br J Gen Pract 2014;64(625):386–387. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp14X680809

10. NHS England. Improving Access for All: reducing inequalities in access to general practice; 2017. https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/improving-access-for-all-reducing-inequalities-in-access-to-general-practice-services/

11. Forbes L, Marchland C, Doran T, Peckham S. The role of the Quality and Outcomes Framework in the care of long-term conditions: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract 2017;67(664):e775-782

https://bjgp.org/content/bjgp/67/664/e775.full.pdf

12. Scottish Government. Practising realistic medicine: Chief Medical Officer for Scotland Annual Report; 2018. https://www.gov.scot/publications/personalising-realistic-medicine-chief-medical-officer-scotland-annual-report-2017-2018/

13. Health Foundation. Person-centred care made simple. What everyone should know about person-centred care. https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/PersonCentredCareMadeSimple.pdf

14. Healthcare Improvement Scotland. ‘What matters to you?’ Supporting more meaningful conversations in day-to-day practice: A multiple case study evaluation; 2019

https://www.whatmatterstoyou.scot/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/20200217-WMTY19-report-FINAL.pdf

15. Coulter A, Robert S, Dixon A. Delivering better services for people with long-term conditions: Building the House of Care; 2013. King’s Fund.

16. Coulter A, Kramer G, Warren T, Salisbury C. Building the house of care for people with long-term conditions: the foundation of the House of Care framework. Br J Gen Pract 2016;66(645):288-290.

17. NHS England. 2019/20 General Medical Services (GMS) contract Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF). Guidance for GMS contract 2019/20 in England

April 2019. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/gms-contract-qof-guidance-april-2019.pdf

18. Cumming S, Steel S, Barrie J. Anticipatory Care Planning in Scotland. Int J Integrated Care 2017;17(3):A130