Advance care planning

Julia Neal

Julia Neal

RGN MSc SFHEA

End of Life Programme Manager, Herefordshire and Worcestershire CCG and Trustee,

KEMP Hospice, Wyre Forest, Worcestershire.

Caitlyn Adkins

RGN

KEMP Hospice Advance Care

Planning Facilitator

Practice Nurse 2020;50(10):26-30

COVID-19 has brought the need for Advance Care Planning into sharp focus. Although it can be a difficult subject to broach, it is vitally important and needs sensitive, timely and structured discussion as a routine part of the personalised care that we deliver

Supporting people to think about and record their wishes in relation to future care and treatment has never been more important. The coronavirus pandemic has brought into sharp focus the value of Advance Care Planning (ACP) and the need for structured and sensitive conversations as a routine part of personalised care planning. ACP is important for everyone, but is a particular priority for those thought to be in the last 12 months of their life, for people living with frailty and those with long term conditions (LTCs). General practice nurses (GPNs) have a key role in empowering people to discuss and negotiate their preferences.

WHAT IS ADVANCE CARE PLANNING?

ACP is a process of formal decision-making through which the wishes of a person, in relation to their medical treatment, are made explicit for the purposes of future circumstances that may mean they are unable to communicate those wishes. It aims to ensure that those people who wish to make decisions receive care ‘consistent with their values, goals and preferences’ during serious and chronic illness.1 This includes planning preferred care, agreeing ceilings of treatment and, where appropriate, making decisions to refuse treatment prior to a crisis situation.

It is important not to think of ACP as a task to be achieved or documented. It is a series of steps in a complex process and will need revisiting regularly to ensure that it reflects the person’s current circumstances.

The Mental Capacity Act allows for three outcomes of ACP, which can come into play when a person no longer has capacity to consent or refuse treatment:

1. Advanced Statements These can be a verbal or written record about medical treatment or social aspects of care. They are not legally binding but should be taken into consideration in the event of decisions about what would be in a person’s best interest.

2. Advance Decisions to Refuse Treatment (Advance Directives or Living Wills) These are legally binding. They document treatments a person would not wish to have, including cardio-pulmonary resuscitation. It does not, however, allow a person to refuse basic care such as warmth or oral fluids.

3. Lasting Power of Attorney (POA) This allows a person to nominate an individual – to give them POA – giving them decision making powers which may relate to either property and finance, or health and welfare.

Negotiating aspects of ACP and the associated documentation can be challenging for patients, their families and for health care professionals (HCPs). There is no national NHS portal for information and resources related to ACP. The available websites are not co-ordinated or accredited and the quality therefore varies. Two good sources of information are:

- My Living Will This provides resources to help plan and produce advance statements and advance decisions.

- PREPARE for your care This includes a variety of resources suitable for diverse communities.

BENEFITS AND BARRIERS

Benefits of ACP

ACP has been shown to improve:

- A patient’s quality of life2

- Patient and family satisfaction and well-being3

- Concordance between the patient and their loved ones at a time of acute deterioration

- Concordance between preferences for care and delivered care.4

It has also been shown to achieve healthcare savings, reduce the number of people dying in hospital,5 and increase the number of people dying in their preferred place.

Despite these benefits, ACP is still not fully embedded in practice because of the many inherent challenges that need to be overcome.

Barriers to ACP

Among the challenges/barriers is limited time.6 Adequate time is particularly important for giving proper explanations and dealing with patients’ reactions.7 Lack of experience, training or preparation is also a barrier (risk). Clinicians can, understandably, be concerned about conversations having unpredictable outcomes which they do not feel equipped to address.6 For patients, a lack of knowledge, including poor health literacy, can be a factor.8 There may also be organisational barriers, including a lack of a suitable template to use or policy to follow, including making roles and responsibilities relating to ACP explicit.9 See Box 1.

Clinicians may feel that not having a sufficiently close relationship with the patient is a barrier to having a discussion about ACP.7 Conversely, they may feel that such discussions may risk jeopardising a trusted existing relationship.9 Given the importance of family involvement in shared decision making, poor family dynamics can also be a barrier.9 Uncertainty is another common barrier. A patient’s prognosis or trajectory may be unclear. There may also be uncertainty about assessing a patient’s readiness to discuss ACP whilst they are still relatively healthy, or do not have a terminal diagnosis.6,9

Ethical concerns can also be challenging. HCPs have reported perceiving that any plans developed may not be actioned.6 They may also be afraid of criticism for any decisions made and documented.7 HCPs can be concerned about removing hope. They may also fear causing maleficence/harm, due to subsequent limitations or ceilings of care being provided, or in any other way that negatively impacts the individual.8

Inequalities are also a factor. Being from a Black, Asian or Minority Ethnic group, having lower educational attainment or a non-cancer diagnosis are all barriers.10 Cultural aspects can impact on a patient’s attitude to health care systems and comfort when it comes to discussing death and decision making. Thus a lack of cultural concordance between the HCP and the patient can also act as a barrier.11

THE ROLE OF THE GPN IN ACP DISCUSSIONS

The importance of ACP is recognised in the Royal College of General Practitioners/Marie Curie UK’s General Practice Core Standards for Advanced Serious Illness and End of Life Care (Daffodil Standards),12 and the Gold Standards Framework for best practice in End of Life Care.13

All HCPs have a responsibility in relation to ACP, the aim of which is to avoid having to make important decisions in a crisis situation when it may not be possible for the individual to express their wishes. It would, almost certainly, be more traumatic to have ACP conversations in such circumstances. GPNs often have the advantage of being able to build relationships with patients and their family/carers over a prolonged period and may be seen as approachable and trustworthy. This places them in a unique position. They can ensure that patients are aware of the significance of thinking about and recording their wishes at an early stage.

Opportunities for ACP discussions should be a focus of your considerations in LTC management,14 as well as for those patients who are on the End of Life (EOL) Register or have been assessed as being severely frail. Timing is key and it may be difficult to judge the readiness of a patient with an LTC to have such a conversation while they are still relatively healthy. They may not yet perceive their condition as life limiting, Such conversations, however, do need to be approached sufficiently early, when patients still have the ability to communicate their wishes.

It is worth remembering that, while clinicians often wait for patients or their relatives to initiate discussions about future care, patients will often expect clinicians to bring the subject up.7 The majority of patients are happy to discuss their future care while their condition is stable.14

It is useful to make sure that the whole practice is aware of the need to have ACP conversations early, so that opportunities for awareness-raising are picked up and patients referred appropriately for conversations to happen. You could be proactive, for example, by checking the practice EOL and Frailty registers to see if patients have had ACP conversations.

Many nurses, however, feel uncomfortable about approaching ACP conversations. This can be harder if a traditional approach is used. Traditional approaches often focus on a narrow, harm reduction strategy of avoiding treatments that the patient has not yet even begun to think about. An approach based on discussing what matters to the patient may feel more comfortable and can help make such clinical discussions easier. A way of achieving this is to focus on three main areas:15

- What matters most to you in life when you are well?

- Which of these will become priorities when you become less well?

- How will you access support once you become less well so that these priorities are achievable?

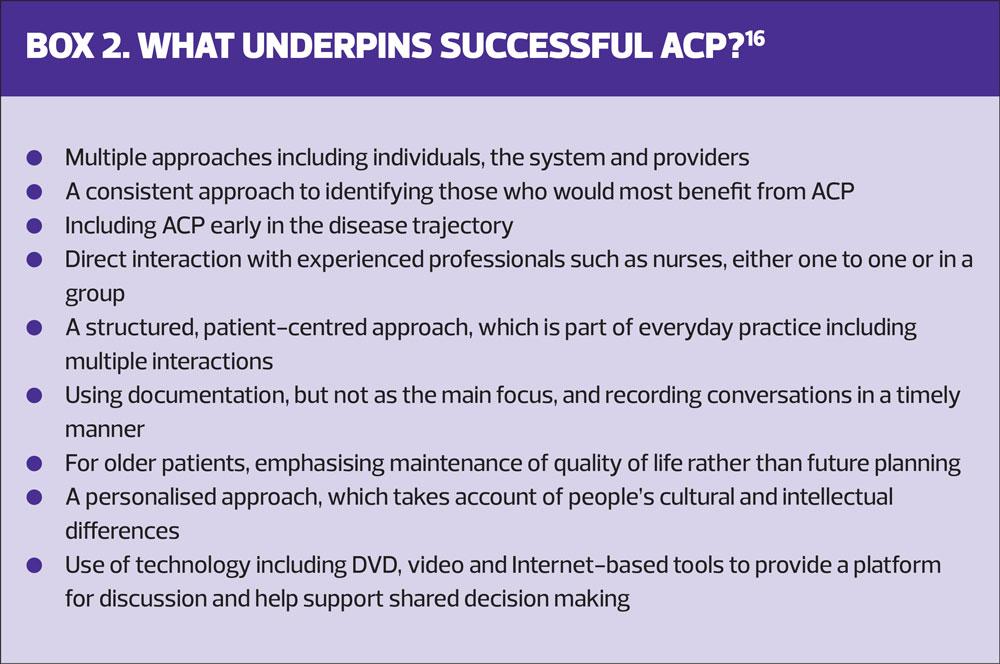

This approach will enable you to concentrate on the patient’s concerns. These will generally be around health and well-being and the social supports that underpin this, rather than the clinician’s priorities which tend to be around final treatment choices.15 This approach will also help your conversations to be more inclusive, more patient-centred and personalised, and enable the involvement of the patient’s loved ones, where this is their wish. You may also find that this approach fits more naturally into discussions about living with an LTC, so that ACP conversations can happen at an earlier stage in your patient’s journey. The evidence supporting successful ACP conversations is summarised in Box 2.

GPN are also well placed to review ACP documents when patients experience a step change in their condition, e.g. following discharge from hospital after a COPD exacerbation. Box 3 suggests factors which should prompt an ACP review.

COMMUNICATING YOUR PATIENT’S WISHES

All members of the team have a role to play in promoting the importance of ACP, from awareness raising, initiating conversations and updating records following a change in the plan. The General Medical Council (GMC) acknowledges that differing services across the health economy have input into patients’ care. The recording of ACP conversations is therefore vital so that the multi-disciplinary team is kept up to date. Nurses should ensure that they adhere to the NMC code in relation to documentation and record keeping. Unfortunately, the lack of a shared record nationally makes joined up communication difficult in some cases, although there are local solutions that have been successful. Electronic Palliative Care Coordination Systems (EPaCCS) are used in many areas to enable ACP and improve communication and coordination at the end of life. However, they are not always fully integrated across all providers.

In some areas a summary form is used, so that all HCPs, including paramedics, can access key information about ACP quickly in an emergency situation. The ReSPECT (Recommended Summary Plan for Emergency Care and Treatment) form documents clinical recommendations as part of ACP to guide clinicians in future decisions if the patient loses the ability to communicate their wishes. Patients keep the form with them to be instantly available and, increasingly, this is available digitally, with shared access across all providers.

Version 3 of the ReSPECT form is now available. The changes incorporated in this version include an opportunity for the patient and/or their relatives to sign stating that they have been involved with the ReSPECT process. This addition follows feedback from patients, families and clinicians. There is also now an opportunity to write a reason for the person lacking mental capacity. This provides another prompt to clinicians to then have discussions with the patient’s relatives or person with POA. The POA information is now referenced on the front of the form to encourage clinicians to establish at an early stage if a person with POA for health and welfare has been appointed.

Case study

Brenda is a 66-year-old housewife living with heart failure. During a 12-month review over the telephone, she reported that she was feeling more short of breath when out shopping with her daughter.

Following a medication review, the nurse went on to check whether there was any record of previous ACP discussions, having recognised the importance of broaching this subject while Brenda was still relatively stable. The conversation about her daily walk led to discussions about what mattered most to Brenda. Brenda admitted to wanting to discuss her wishes with her family, but had never found the right time. The nurse was able to signpost Brenda to https://www.mylivingwill.org.uk/ and, at a following appointment they looked through the Advance Statement together.

Brenda had been able to think about what was important to her and the nurse was able to talk through her concerns and help her articulate her wishes in relation to future care and treatment. This led onto a discussion about cardio-pulmonary resuscitation, during which the nurse was able to allay some of Brenda’s misconceptions. The nurse also discussed the ReSPECT process as a way of making sure that she had a document with her explaining her wishes should she be too poorly to discuss them. Brenda agreed to discuss it with her daughter and a follow up consultation was arranged for the following week to complete the document.

THE IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON OUR APPROACH TO ACP

During the pandemic, because of the potential increase in the numbers of people dying, as well as the speed in which people can deteriorate, there has been a focus, in some areas, on the importance of ACP discussions taking place early, and in the community rather than a hospital setting. Unfortunately, in some cases this has led to a less personalised approach being taken, resulting in media reports of blanket decisions being made in relation to certain demographic groups.

However, these public discussions have led to a greater awareness of the need for ACP and the importance of not avoiding such conversations. ACP provides a real opportunity to increase your patient’s autonomy at a time when they may feel more out of control than ever in their lives. In some areas the use of touchpoints, such as well-being calls, have been used as an opportunity to initiate ACP awareness raising.

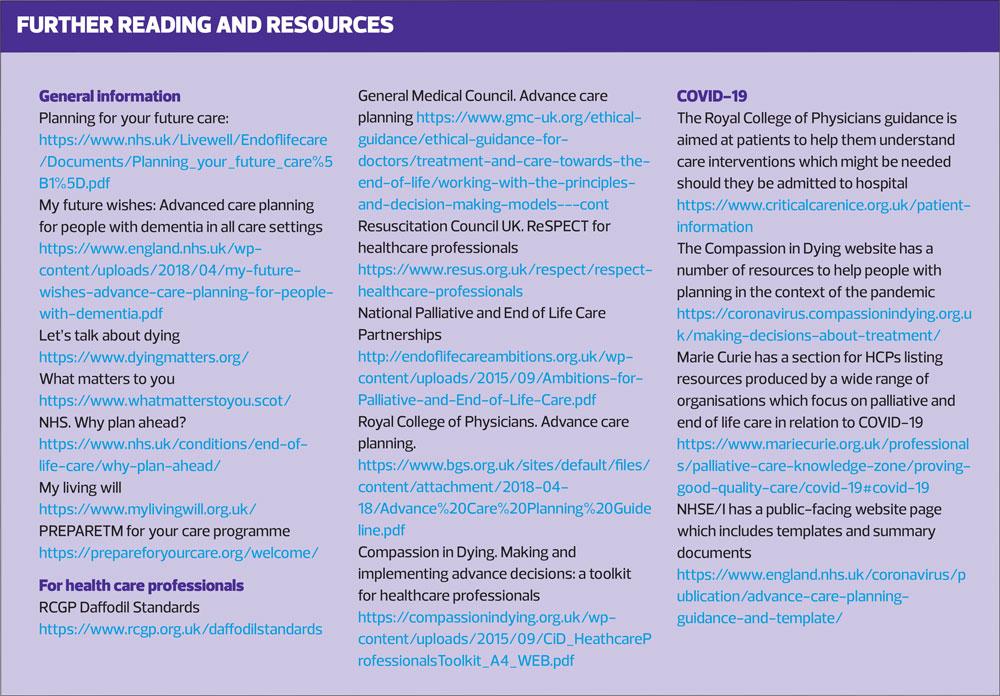

A number of resources have been produced to help HCPs support ACP during the pandemic and these are included in the resources list at the end of this article. Some of the barriers to ACP have been exacerbated by COVID-19 restrictions, although the use of remote consultations are an important way of supporting the face to face and group discussions which are known to support successful ACP. Remote consultations can and are being used to ensure that these important conversations can still take place safely.

ACP FACILITATORS

During the pandemic HCPs have evolved their roles to work round the necessary restrictions. The role of the Advance Care Planning Facilitator was introduced by KEMP Hospice and funded by Herefordshire and Worcestershire CCG to enable better quality and more consistent ACP discussions with care home residents. This is normally achieved through face-to-face education and training, and modelling conversations with residents and their families for care home staff. During COVID-19 these discussions have all taken place over the telephone or using video call. Nursing staff at KEMP, redeployed from the day hospice, have also assisted with these conversations.

Following information from the care home that there is a new resident, the ACP Facilitator gathers information, exploring capacity, health conditions and communication needs from the person’s medical notes and the care home staff. The subject is introduced by care home staff to residents early on in their stay and they and their family are given the opportunity for a remote appointment with the ACP Facilitator.

In Worcestershire, the ReSPECT process is used. Discussions about what matters to the resident normally leads to an opportunity to discuss ReSPECT, and the care home staff ensure there is a sample copy for the resident and their family to look at. Once the resident is ready, each section is discussed and the form completed. This may take several consultations depending on the person’s readiness to discuss their wishes. The ACP Facilitator then discusses this with the appropriate GP/Advanced Nurse Practitioner to ensure that the resident’s records are updated. The form is then delivered to the resident’s care home so that it is with them should it be needed.

SUMMARY

ACP is an important way of supporting people to think about what matters to them in the event of future deterioration in their health, and to be able to communicate this appropriately. It can be challenging for HCPs to do this effectively but it is an important part of the GPN role, particularly during the current pandemic. A personalised and patient-centred approach should be taken and there are a number of resources to support people to make decisions and record their wishes.

REFERENCES

1. Sudore S, Lum R, You J, et al. Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition from a multidisciplinary delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017;53(5):821-832 doi:20217 53 821 832

2. Kononovas K, McGee A. The benefits and barriers of ensuring that patients have advance care planning. Nursing Times 2017; 113(1): 41-44.

3. Detering K. Hancock A, Reade M, et al. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010: 340 c1345 doi 10.1136/bmj.c1345

4. Houben C, Spruit M, Groenen M, et al. Efficacy of advance care planning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2014; 15: 477-489

5. Dixon J, King D, Knapp M. Advance care planning in England: Is there an association with place of death? Secondary analysis of data from the National Survey of Bereaved People. BMJ Supp Palliat Care 2019;9:316–325. doi:10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-000971

6. Lund S, Richardson A, May C. Barriers to advance care planning at the end of life: an explanatory systematic review of implementation studies. PLoS One 2015: 10(2: e0116629, di:10.1371/journal.pone.0116629

7. Kastbom L, Milberg A, Karlsson M. ‘We have no crystal ball’ – advance care planning at nursing homes from the perspective of nurses and physicians. Scand J Prim Health Care 2019; 37 (2): 191-199.

8. Helmsley B, Meredith J, Bryant L, et al. An integrative review of stakeholder views on advance care directives (ACDs): barriers and facilitators to initiation, documentation, storage and implementation. Patient Educ Couns 2019; 102: 1067-1079

9. Risk J, Mohammadi L, Rhee J, et al. Barriers, enablers and initiatives for uptake of advance care planning in general practice: a systematic review and critical interpretive synthesis. BMJ open 2019 9e030275,doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030275

10. Lovell A, Yates P. Advanced care planning in palliative care: a systematic literature review of the contextual factors influencing factors its uptake 2008 -2012. Palliat Med 2014; 28(8) 1026 – 1035

11. Royal College of General Practitioners Gold Standards Framework. The GSF prognostic indicator guidance. 2011 4th Edition. https://www.goldstandardsframework.org.uk/cd-content/uploads/files/General%20Files/Prognostic%20Indicator%20Guidance%20October%202011.pdf

12. Royal College of General Practioners, Marie Curie UK. General Practice Core Standards for Advanced Serious Illness and End of Life Care. 2018 https://www.rcgp.org.uk/daffodilstandards

13. Mc Dermott E, Selman L. Cultural factors influencing advance care planning in progressive, incurable disease: a systematic review with narrative synthesis. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018; 56 (4): 613-636

14. Conroy S, Fade P, Fraser A, et al. Advance care planning: concise evidence-based guidelines. Clin Med 2009; 9:76–79 PMiD 19271609

15. Abel J, Kellehear A, Millington Saunders C, et al. Advance care planning re-imagined: a needed shift for COVID times and beyond. Palliative Care and Social Practice. 2020;14: 1-8 doi: 10.1177/2632352420934491

16. Hamilton I. Advance care planning in general practice: promoting patient autonomy and shared decision making. BJGP 2017; 67 (656):104-105

17. Selman L, Lapwood S, Jones N, et al. Advance care planning in the community in the context of COVID-19. https://www.cebm.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/ACP-in-COVID-review-17.8.2020.pdf