Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: the importance of early detection in primary care

Dr GERRY MORROW

Dr GERRY MORROW

MB ChB MRCGP Dip CBT

Editor CKS, Medical & Product Director (Primary Care) Agilio Software

Practice Nurse 2022;52(6):24-28

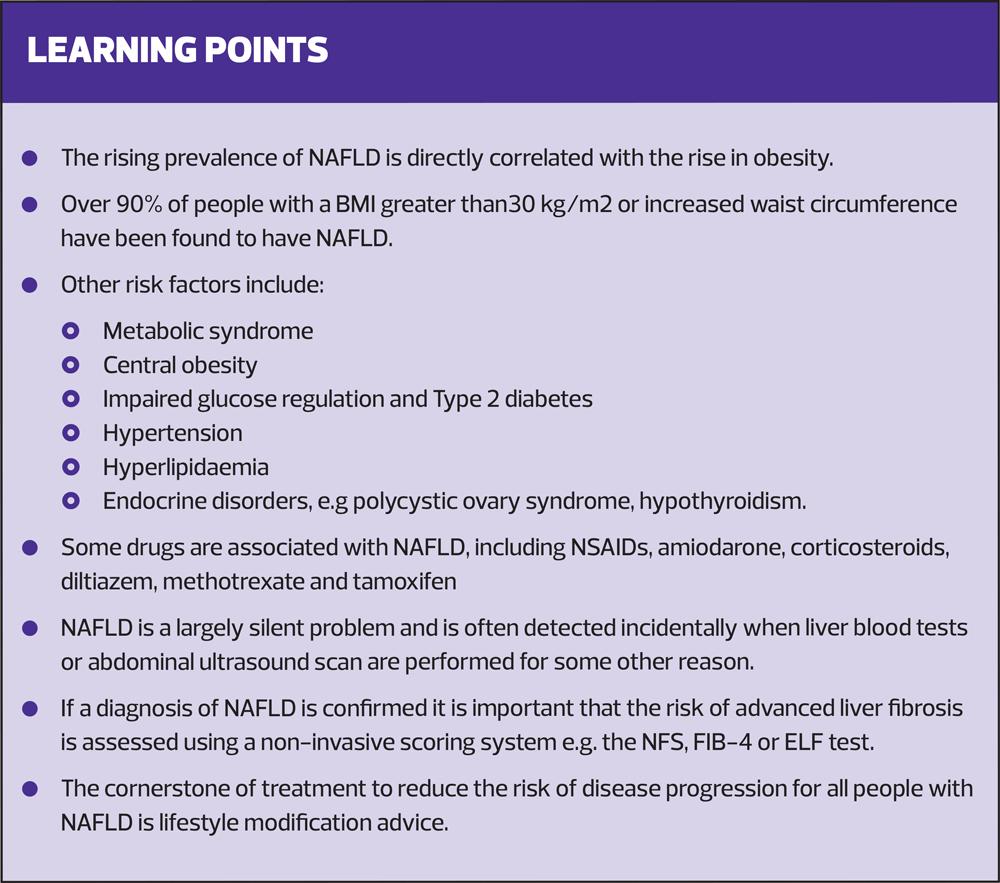

The prevalence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is directly correlated with the rise in obesity, and is set to become the most common reason for liver transplantation worldwide. Prognosis is poor for those with advanced disease but effective management by practice nurses can improve outcomes

Primary non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) refers to excess fat accumulation (steatosis) in the liver, where triglycerides are present in more than 5% of hepatocytes, and which is not the result of excessive alcohol consumption or other secondary causes.1,2

NAFLD ranges from hepatic steatosis through to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), where there is steatosis coexisting with hepatocellular injury and inflammation, with risk of progression to advanced liver fibrosis and cirrhosis.1

NAFLD is a silent problem for most people. Occasionally, however, it can cause non-specific symptoms of fatigue, general malaise, and abdominal discomfort.3

PREVALENCE AND CAUSES

NAFLD is the most common cause of abnormal liver blood test results in the UK,4 and one of the most important liver diseases worldwide. It is anticipated that it will become the leading reason for transplantation.5 The rise in prevalence parallels the increasing prevalence of obesity.6

Prevalence increases with increasing age, and is highest in males aged 40–65 years. The global prevalence of NAFLD is estimated to be 24%.7

The cause is not fully understood. It is likely to be closely linked to insulin resistance, obesity, and the metabolic syndrome.3 However, alcohol consumption and obesity combined have been found to increase the risk of liver disease morbidity and mortality.8

RISK FACTORS

Risk factors for NAFLD include metabolic syndrome and central obesity.9 Over 90% of people with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 or increased waist circumference have been found to have NAFLD.10

Other risk factors include:

- Impaired glucose regulation

- Type 2 diabetes

- Hypertension

- Hyperlipidaemia

- Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome

- Endocrine disorders, e.g. polycystic ovary syndrome and hypothyroidism.2,8

A family history of NAFLD can be an additional risk and there is a higher risk in Hispanic and Asian people, and lower risk in black people.

Some drugs are also associated with NAFLD, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, amiodarone, corticosteroids, diltiazem, methotrexate, and tamoxifen.

COMPLICATIONS

Complications of NAFLD include morbidity and mortality from liver and cardiovascular disease. Cardiovascular disease is the most common cause of death in people with NAFLD.11 People with NAFLD are also more at risk of developing hypertension, chronic kidney disease, impaired glucose regulation, and type 2 diabetes.1

Rare hepatic complications include portal hypertension, variceal haemorrhage, liver failure, hepatocellular carcinoma, and sepsis.9

PROGNOSIS

The prognosis of NAFLD depends on the stage of disease and the presence of co-morbidities. If a person is overweight or obese, or has type 2 diabetes, they are at increased risk of progressive disease.1 For an individual with simple steatosis, the prognosis is good. Cirrhosis develops in only 0–4% of people with simple steatosis and over 10–20 years, there is very slow, if any, progression. If, however, a person has the sub-group NASH, they have an increased risk of progressive liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, liver failure, and hepatocellular cancer.3

DIAGNOSIS

In most people, NAFLD is detected incidentally when liver blood tests or abdominal ultrasound scan are performed for some other reason. You should, however, suspect NAFLD in a person if they have:

- Risk factors suggestive of the metabolic syndrome or other risk factors for NAFLD

- Persistently elevated liver blood tests for 3 months or more

- Upper abdominal ultrasound scan findings consistent with fatty liver changes, no excess alcohol intake and negative blood tests for other causes of hepatic disease.1,4,6

Assessment

In a person with suspected NAFLD you should ask about any symptoms, such as fatigue and right upper quadrant abdominal pain. You should also enquire about the presence of any risk factors for NAFLD, their alcohol intake and any co-morbidities and medication history.

Examine the person. In particular check their height and weight, BMI, and waist circumference. Check the blood pressure and assess for signs of advanced liver disease. These include jaundice, facial spider naevi, palmar erythema, ascites, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, or encephalopathy.

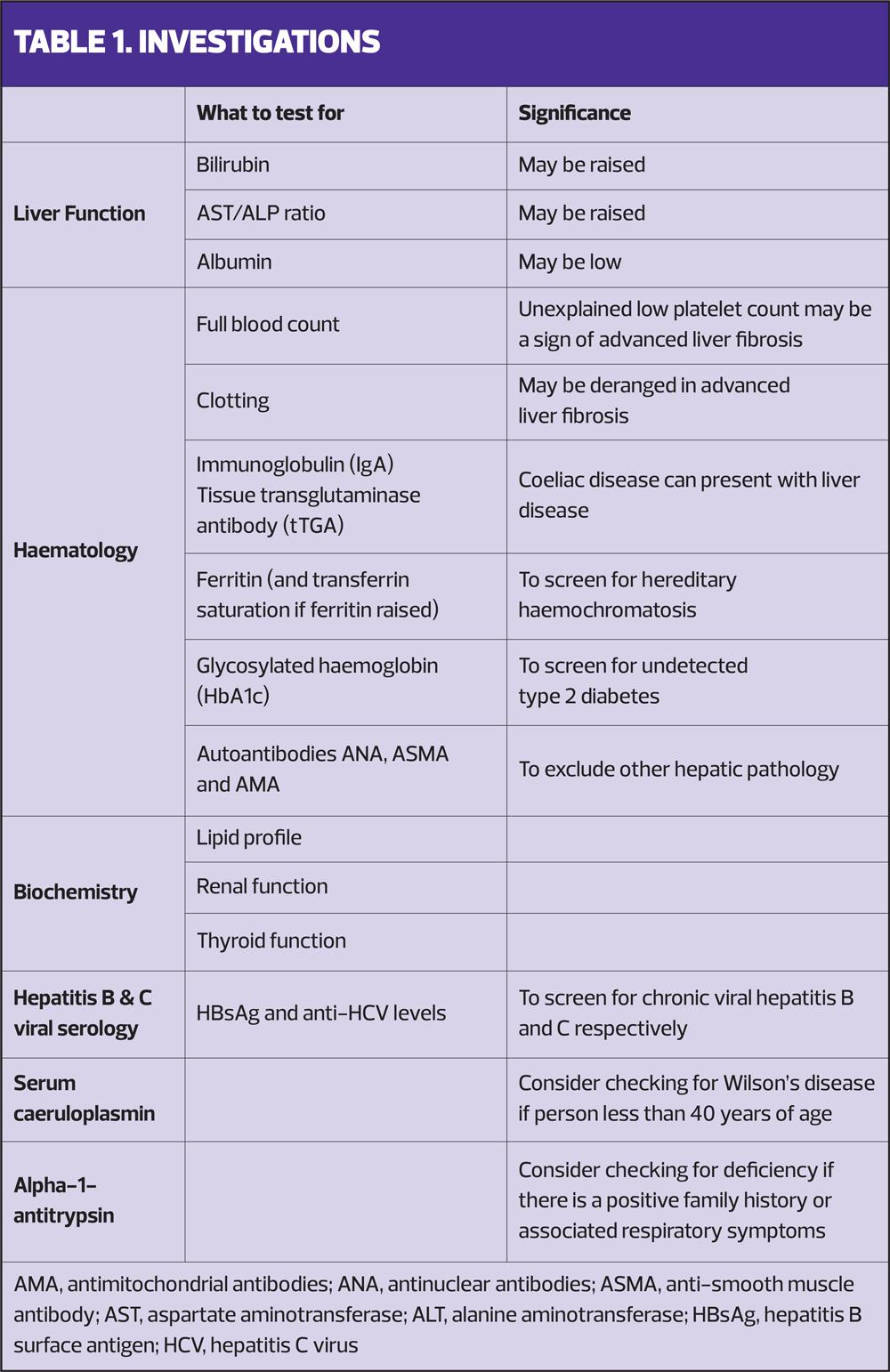

Investigations

There are a range of blood tests that should be considered when faced with an individual who may have NAFLD (Table 1).1

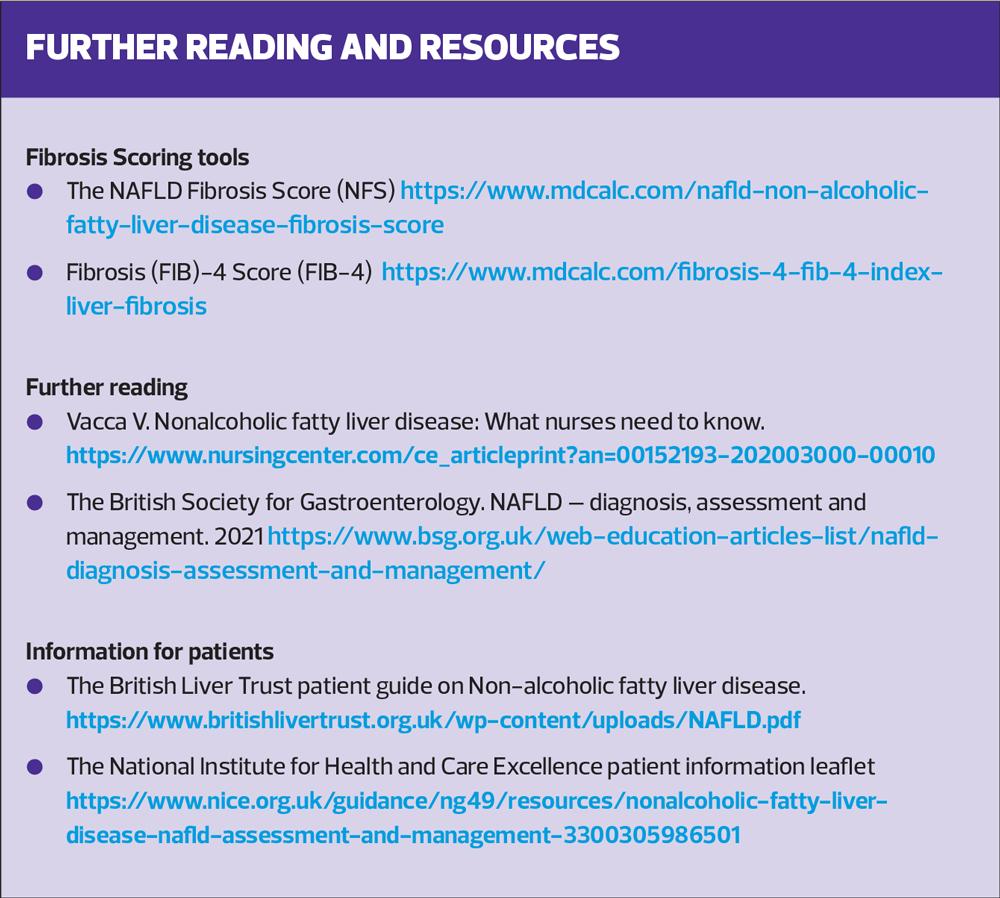

If a diagnosis of NAFLD is confirmed it is also important that the risk of advanced liver fibrosis is assessed using a non-invasive scoring system. (See Resources and Further Reading.)

The NAFLD Fibrosis Score (NFS) estimates the amount of scarring in the liver based on age, BMI, the presence or absence of diabetes or an impaired fasting glucose, the aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level, the platelet count, and the albumin level. An intermediate or high score (greater than –1.455) suggests advanced liver fibrosis.1,9

Fibrosis (FIB)-4 Score (FIB-4) looks at age, AST, ALT and platelet count. A score of greater than 2.67 suggests advanced liver fibrosis.1,9

Enhanced Liver Fibrosis (ELF) test is a blood test that measures three molecules involved in liver matrix metabolism. A score of 10.51 or above suggests advanced liver fibrosis.1,9

PRIMARY CARE MANAGEMENT

It is appropriate for a person with a working diagnosis of NAFLD to be managed in primary care, providing other causes of liver disease have been excluded and there is a low risk of advanced liver fibrosis, assessed using the non-invasive testing scores above (NFS, FIB-4 or ELF).9

The person needs to be advised that, although there is currently no specific drug treatment for NAFLD, the aim of management is to reduce progression and to reduce the risks of cardiac and liver-related morbidity and mortality.1 Primary care management is therefore centred on lifestyle modification advice: diet, physical activity, and regular exercise. This is the cornerstone of treatment for everyone with NAFLD and is a key role for general practice nurses.

- Encourage gradual sustained weight loss, especially if a person is overweight or obese.

- Provide advice on drinking alcohol within national recommended limits.

You should also ensure that associated conditions such as hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, and type 2 diabetes are optimally managed.

In addition patients also benefit from advice on sources of information and support for people with NAFLD. (See Resources and Further Reading.)

Ensure a person with NAFLD who has a low risk of advanced liver fibrosis is reviewed annually.1 During a review:

- Examine the person to check for signs of advanced liver disease

- Measure their blood pressure and check their weight and BMI

- Arrange blood tests to assess for metabolic risk factors, and renal function tests to assess for chronic kidney disease.1

In addition check their HbA1c, to assess for impaired glucose regulation and type 2 diabetes. Check their lipid profile and reassess their risk of cardiovascular disease annually. Their risk of advanced liver fibrosis needs to be reassessed every 3 years.1

REFERRAL AND SPECIALIST INTERVENTIONS

Refer people with suspected or confirmed NAFLD to a hepatology specialist for further assessment and management if:

- The person is at high risk of advanced liver fibrosis

- There are signs of advanced liver disease on examination, or

- There is uncertainty about the diagnosis.1

Specialist interventions

Specialist investigations may include transient elastography (fibroscan) and liver biopsy.11,12 Fibrotic livers have reduced elasticity, and transient elastography is a non-invasive test which measures liver stiffness, which correlates with the degree of liver fibrosis.

Liver biopsy may be needed to confirm the diagnosis of NASH or cirrhosis, to exclude other liver disease, and to decide on the need for further management and monitoring in secondary care. It also may be needed where non-invasive tests for the evaluation of liver disease severity suggest advanced fibrosis, or where the results of such, are inconclusive.

Liver biopsy can provide evidence of the degree of hepatic steatosis, hepatocellular injury, inflammation, and fibrosis, and provides both diagnostic and prognostic information on liver fibrosis and the potential for progression.

Specialist management may include specific monitoring of people with advanced liver disease for hepatocellular cancer using ultrasound scans and alpha-fetoprotein serum monitoring.

In secondary or tertiary care, pioglitazone or vitamin E drug treatment may be considered for adults with advanced liver fibrosis.

Specialist care can also include bariatric surgery and liver transplantation.

NASH will soon become the most common indication for liver transplantation in the US. The results of this are positive for some but it is important to note that NASH may recur after liver transplantation.

CONCLUSION

Given the rising and often hidden problem that is NAFLD it is crucially important, when it is diagnosed, that successful interventions are put in place. General practice nurses can have a pivotal role in the management of people with NAFLD as they are usually also managing those most at risk, including people with diabetes, hypertension, and metabolic syndrome.

REFERENCES

1. NICE NG49. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): assessment and management; 2016 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng49

2. Rikhi R, Singh T, Modaresi Esfeh, J. Work up of fatty liver by primary care physicians, review. Ann Med Surg 2020;50:41-48. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2049080120300042

3. World Gastroenterology Organization. World Gastroenterology Organization global guidelines: non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 2014;48(6):467-473. https://www.worldgastroenterology.org/guidelines/nafld-nash/nafld-nash-english

4. British Liver Trust, Royal College of General Practitioners. Non-alcohol-related fatty liver disease and its primary care management. https://elearning.rcgp.org.uk/mod/book/tool/print/index.php?id=13042

5. Younossi Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M, et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;15(1):11-20. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28930295/

6. Sattar N, Forrest E, Preiss D. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMJ 2014;349:g4596 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4168663/

7. Ye Q, Zou B, Yeo Y H, et al. Global prevalence, incidence, and outcomes of non-obese or lean non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020;5(8):739-752.

8. Hart CL, Morrison D S, Batty GD, et al. Effect of body mass index and alcohol consumption on liver disease: analysis of data from two prospective cohort studies. BMJ 2010;340:c1240 https://www.bmj.com/content/340/bmj.c1240

9. European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD), European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL–EASD–EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of Hepatology 2016;64(6):1388-402

10. Bedogni G, Nobili V, Tiribelli C. Epidemiology of fatty liver: an update. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20(27):9050-9054. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4112887/

11. Mantovani A, Dauriz M, Sandri D, et al. Association between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and risk of atrial fibrillation in adult individuals: An updated meta-analysis. Liver Int 2019;39(4):758-769. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/liv.14044

12. Sawangjit R, Chongmelaxme B, Phisalprapa P, et al. Comparative efficacy of interventions on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): A PRISMA-compliant systematic review and network meta-analysis. Medicine 2016;95(32):4529. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4985329/

Related articles

View all Articles