Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: hiding in plain sight

Beverley Bostock-Cox

Beverley Bostock-Cox

RGN MSc MA QN

Nurse Practitioner Mann Cottage Surgery

Education Lead Education for Health

The incidence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is increasing in parallel to increased prevalence of obesity and subsequent development of type 2 diabetes, and as in type 2 diabetes, lifestyle measures are key to management

Although alcohol intake is often recognised as a cause of liver disease, obesity is often overlooked, despite the fact that statistics on liver disease suggest that NAFLD is the most common cause of abnormal liver function tests and liver disease with approximately a third of the population being affected.1

In this article we discuss the importance of recognising risk factors for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and why early identification and intervention is an important part of the role of general practice nurses (GPNs).

By the end of this article you will be able to:

- Recognise why NAFLD is important cause of morbidity and mortality

- Identify risk factors

- Understand the role of tests in diagnosing NAFLD

- Implement strategies to reduce the risk of complications

- Refer appropriately

DEFINITION AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is caused by fat being deposited in the liver, a condition known as steatosis. NAFLD may be the result of simple fatty liver, also known as non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFL), to distinguish it from another type of non-alcoholic liver disease, non-alcoholic steato-hepatitis (NASH). In NAFL there are fatty deposits in the liver but little or no evidence of inflammatory change. NAFL is a much more benign version of fatty liver disease and rarely leads to complications. Conversely, as its name suggests, NASH is complicated by inflammatory change within the liver cells which can lead to fibrosis and, ultimately, cirrhosis. NASH is also associated with liver cancer. Of the two types of fatty liver disease, NASH is far less common and most people with NAFLD have simple fatty liver. Only a small number of people with NAFLD will have NASH, with studies suggesting figures of between 1.5-6.5% of the global population being affected.2 However, as diagnosis of NASH requires histological evidence these figures are only a guide.

In NAFLD, obesity leads to fat being deposited in the liver in the same way that it is laid down in other areas of the body. However, fat is known to be an active substance which has an inflammatory action within the body leading to other conditions such as cardiovascular disease.3 Cardiovascular disease and cancers are common causes of death in people who have either form of NAFLD.4

It is thought that the factors that trigger NAFLD to become the more serious NASH, include fat deposits in the gut, lipotoxicity, innate immune responses, cell death pathways, mitochondrial dysfunction and endoplasmic reticulum stress. Defective responses to inflammation within the body are also thought to facilitate the change from straightforward NAFLD to NASH.5

RISK FACTORS

NAFLD is strongly associated with obesity (body mass index of 30kg/m2 or more) and associated conditions such as metabolic syndrome or type 2 diabetes. However, there is also a ‘chicken and egg’ situation in this relationship as raised liver fat levels are also associated with hepatic insulin resistance, inadequate suppression of hepatic glucose production, and raised fasting plasma glucose, increasing the risk of diabetes in those who do not already have it.6

The age group most likely to be affected by NASH is the population aged 40-50 years and progression to cirrhosis is mainly seen in those aged 50-60 years. However, there is also an increase in fatty liver disease in children and young people, reflecting current trends in obesity and type 2 diabetes in this group. It is thought that around 40% of obese children will have NAFLD.

DIAGNOSIS

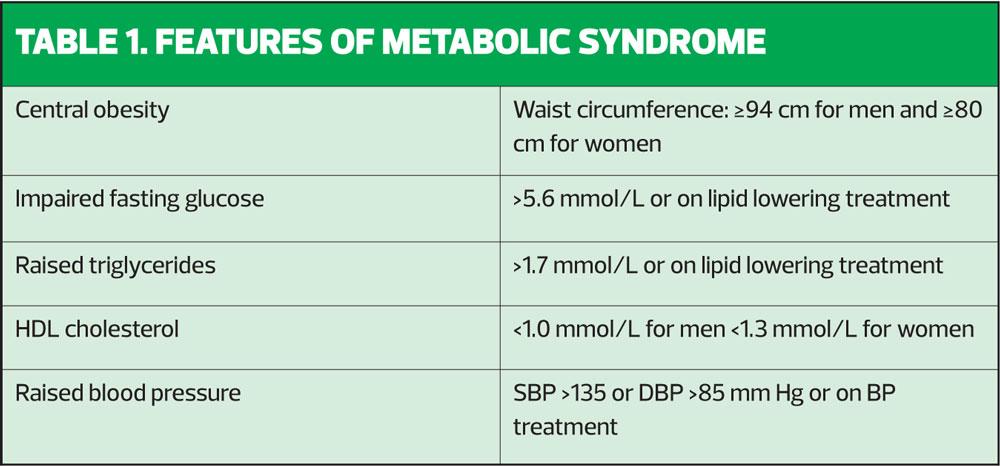

NAFLD should be suspected in anyone with a BMI of 30kg/m2 or more, especially if they have features of metabolic syndrome or a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes. Features of metabolic syndrome are listed in Table 1. As NAFLD is specifically non-alcohol related, a history of alcohol consumption should be taken to rule out alcohol-related liver disease, which will need a different approach and broader involvement of the multi-disciplinary team.

The most common symptoms of NAFLD are tiredness and malaise. Other symptoms may include right upper quadrant pain, which may be related to hepatosplenomegaly, a relatively common sign in NAFLD. Blood tests may be undertaken to determine the cause of these signs and symptoms but may be normal. Liver transaminases, specifically alanine transaminase (ALT) and/or gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT) cannot be relied upon to identify those with or at risk of NAFLD as they are most often normal or only mildly abnormal.8 Furthermore, as the disease advances through fibrosis to cirrhosis, the ALT level may fall, giving a false negative result. Overall, liver function tests do not correlate with findings on biopsy so should not be used to diagnose or stage NAFLD. Research has shown that around three quarters of people who are centrally obese and around half to three quarters of people diagnosed with type 2 diabetes have evidence of NAFLD when they have been referred for scans.9

The NAFLD Liver Fat Score uses parameters such as pre-existing metabolic syndrome and/or type 2 diabetes along with fasting serum insulin, fasting serum AST and the AST/ALT ratio (AAR) to calculate liver fat. Kotronen et al10 showed that a score of more than –0.640 effectively predicted NAFLD, although it could not identify what stage it was.10 It can be difficult to differentiate simple steatosis from steato-hepatitis without invasive investigations but patients with more metabolic abnormalities have generally been found to be at greater risk of inflammatory change, fibrosis and cirrhosis.

The gold standard test for both diagnosis and staging of NAFLD is liver biopsy, an invasive and, for most people, unpleasant investigation. However, studies suggest that the majority of patients can be effectively diagnosed non-invasively with routine scans including standard ultrasound, which will effectively diagnose NAFLD as long as around one third of liver cells are affected. Other investigations, used less often in the diagnosis of NAFLD and NASH, include magnetic resonance imagery (MRI), proton MR spectroscopy and transient elastography.11

NON PHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT

In line with the underlying causes of NAFLD, the most effective approach to both prevention and management will be lifestyle-based. There is some evidence to suggest that inactivity is specifically linked to the risk of NAFLD so people at risk (including those who have not yet been diagnosed) should be given advice on how to be more physically active as well as offered dietary advice in line with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommendations.12 In the small number of cases where the individual with NAFLD is not obese (where discussion on diet will often reveal a high intake of fat and sugar) recommendations on healthy lifestyle will still apply.

The key recommendations for dietary interventions from NICE included the importance of a tailored, flexible and individualised approach based on healthy eating. NICE recommends aiming for a 600 calorie deficit (i.e. reducing calorie intake versus expenditure by 600 calories a day) but suggests that low calorie diets (800-1600 calories a day) may be appropriate for some individuals as long as they are nutritionally complete. NICE advises that very low calorie diets (VLCDs) of less than 800 calories should be undertaken only with supervision and for no longer than 12 weeks (continuously or intermittently).

The Diabetes Remission Clinical Trial (DiRECT) study13 has increased interest in these VLCDs as an intervention that can lead to diabetes remission. The DiRECT study offered an intensive weight loss programme aimed at supporting people to lose 15kg in a 12-week period. Study participants attended their own GP practice to be supported by their own GPN (or in some cases, if a GPN was not available, a dietician). Participants were offered two one-hour long appointments on a one to one basis and were then offered follow up appointments of around 30 minutes. Participants were aged 20–65 years and had a BMI of between 27–45kg/m2. The diet itself was a VLCD consisting of meal replacement shakes and soups to a total daily value of 830kcal with 61% being carbohydrate, 26% protein and 13% fat. Participants were also encouraged to be physically active for 30 minutes a day. After a minimum of 12 weeks and a maximum of 20, food was gradually reintroduced to the diet by adding a 400 kcal meal every 2-3 weeks. The findings of the study showed that of the 149 participants, 36 achieved a weight loss of 15kg or more – i.e. 24% of the study group. No-one in the control group (n149) achieved this, making the result highly statistically significant. However, the effect on liver fat could be of particular interest for people with NAFLD as liver fat content was normalised and pancreas fat content decreased in all participants who lost weight, even if their HbA1c remained high.14 During a very low-calorie diet in type 2 diabetes, an initial study showed that liver fat content rapidly decreased, with normalisation of hepatic insulin sensitivity within 7 days.15

In a meta-analysis of lifestyle interventions for people with NAFLD by Zou et al, aerobic exercise training plus diet led to a significant improvement of ALT and AST levels, and important improvements in BMI and insulin resistance scores.16 Progressive resistance training led to improvements in insulin resistance scores but it did not affect BMI. Overall, in this meta-analysis, dietary intervention appeared to be more effective in improving liver function tests, whereas exercise was better at improving insulin sensitivity and reducing BMI.

Interestingly, another meta-analysis by Ma et al showed that probiotic use could reduce liver enzymes and total-cholesterol and improve insulin resistance in people with NAFLD patients via modulation of the gut microbes, an area that has produced a lot of interest in recent years.17

PHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT

There are currently no licensed pharmacological options for treating NAFLD. However, medications which support weight loss may be the preferred option for people with diabetes. These include the SGLT2 inhibitors and the GLP1 receptor agonists.18 The GLP1-RA liraglutide, marketed as Saxenda, is licensed to support weight loss in people without diabetes who have a BMI over 27kg/m2. No dose adjustment is required for patients with mild or moderate hepatic impairment but it is not recommended for use in patients with severe hepatic impairment.19

People with NAFLD who are taking statins should continue to take them as they are at increased risk of developing cardiovascular disease. Statins are metabolised through the liver but they should only be stopped if liver function tests double within 3 months of starting statins, even if they were abnormal at the start of treatment. Abnormal liver function tests in people with NAFLD are not a reason to avoid statins.

It is important to ensure that patients with NASH are referred to a hepatology specialist. Specialist centres may be involved in trials looking at new potential treatments or they may decide to offer a trial of pioglitazone off licence (but as recommended by NICE) for adults with advanced fibrosis based on previous evidence and the risk: benefit ratio. This may also be an important drug to use in people with diabetes and NAFLD.20 Vitamin E may also be prescribed by specialist centres for advanced fibrotic disease.

ONGOING MONITORING – COMPLICATIONS

In patients with NAFLD, especially those who are obese, there is an increased risk of other health problems in the future, such as type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, dyslipidaemia, atrial fibrillation and chronic kidney disease. Many of these risks will be reduced with appropriate weight loss interventions based around lifestyle change. Ongoing support should be offered along with appropriate screening and management. The multi-disciplinary team, including dieticians, counsellors and local healthy lifestyle schemes can have an important role in this work.

People who are known to have NAFLD or NASH should be monitored for cirrhosis, particularly if they are known to have other risk factors for cirrhosis including a previous hepatitis infection (B or C), or who drink above the recommended 14 units of alcohol per week.

CONCLUSION

NAFLD comprises simple fatty liver (steatosis) and steato-hepatitis where inflammation is present. Although simple fatty liver is a relatively benign condition it may be a predictor of other health problems in the future. NASH is an important cause of morbidity and mortality as it can lead to liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. Obesity, metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes are key risk factors. Blood tests are often normal in NAFLD and the diagnosis can only be confirmed and staged with liver biopsy. However, non-invasive tests such as risk calculators and scans may also be used. Lifestyle interventions are absolutely central to the management of NAFLD although there may be a role for some drug therapies, depending on individual circumstances. Patients with NAFLD should have ongoing support and be monitored for potential complications. Anyone with a diagnosis of NASH with liver fibrosis should be under specialist care.

REFERENCES

1. NICE NG49. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): assessment and management, 2016 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng49/

2. Younossie Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M, et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;15:11-20

3. Ellulu MS, Patimah I, Khaza’ai H, et al. Obesity and inflammation: the linking mechanism and the complications. Arch Med Sci 2016;13(4):851–863. doi:10.5114/aoms.2016.58928

4. Wilde SH, Walker JJ, Morling JR, et al. Cardiovascular Disease, Cancer, and Mortality Among People With Type 2 Diabetes and Alcoholic or Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Hospital Admission Diabetes Care 2018;41(2):341-347 https://doi.org/10.2337/dc17-1590

5. Farrell GC, Haczeyni F, Chitturi S. Pathogenesis of NASH: How metabolic complications of overnutrition favour lipotoxicity and pro-inflammatory fatty liver disease. Adv Exp Med Biol 2018;1061:19-44 doi: 10.1007/978-981-10-8684-7_3

6. Kitade H, Chen G, Ni Y, et al. Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Insulin Resistance: New Insights and Potential New Treatments. Nutrients 2017:9(4):387. doi:10.3390/nu9040387

7. Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, et al. Harmonizing the Metabolic Syndrome Circulation 2009;120:1640-45 https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/pdf/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644

8. Mofrad P, Contos MJ, Haque M, et al. Clinical and histologic spectrum of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease associated with normal ALT values. Hepatology 2003;37:1286–92.

9. Williams CD, Stengel J, Asike MI, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis among a largely middle-aged population utilizing ultrasound and liver biopsy: a prospective study. Gastroenterology 2011;140:124–31.

10. Kotronen A, Peltonen M, Hakkarainen A, et al. Prediction of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and liver fat using metabolic and genetic factors. Gastroenterology 2009;137:865–72.

11. Dyson JK, Anstee QM, McPherson S. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a practical approach to diagnosis and staging Frontline Gastroenterology 2014;5:211-218.

12. NICE CG189. Obesity: identification, assessment and management, 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg189/

13. Lean MEJ, Leslie WS, Barnes AC, et al. Primary care-led weight management for remission of type 2 diabetes (DiRECT): an open-label, cluster-randomised trial Lancet 2017;391(10120):541-551. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)33102-1

14. Taylor R, Al-Mrabeh A, Zhyzhneuskaya S, et al., Remission of Human Type 2 Diabetes requires decrease in liver and pancreas fat content but is dependent upon capacity for ? cell recovery. Cell Metabolism 2018;28(4):547-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2018.07.003

15. Lim EL, Hollingsworth KG, Aribisala BS, et al. Reversal of type 2 diabetes: normalisation of beta cell function in association with decreased pancreas and liver triacylglycerol. Diabetologia 2011;54:2506–14.

16. Zou TT, Zhang C, Zhou YF, et al. Lifestyle interventions for patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a network meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018;30(7):747–755 DOI: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000001135

17. Ma YY, Li L, Yu C-H, Shen Z, et al. Effects of probiotics on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19(40):6911–18. doi:10.3748/wjg.v19.i40.691

18. Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, et al. Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, 2018. A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2018;41(12):2669-2701 https://doi.org/10.2337/dci18-0033

19. Saxenda Summary of Product Characteristics, 2018. https://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/product/2313/smpc

20. Cusi K. Treatment of patients with type 2 diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: current approaches and future directions. Diabetologia 2016;59(6), 1112–1120. doi:10.1007/s00125-016-3952-1

Related articles

View all Articles