The vital role of nurses in HIV care

Breda Patterson

Breda Patterson

National Market Access Senior Manager for HIV, Gilead Sciences Ltd

This non-promotional article has been developed by Gilead, who have reviewed it for accuracy and compliance with the pharmaceutical industry code of practice.

Job code: UK-UNB-3091

Date of Preparation: October 2022

Practice Nurse 2022;52(8):16-19

HIV has transformed over the past 20 years, but the role that nurses play continues to be as important as ever

In 2007, Breda Patterson became the first advanced nurse practitioner for HIV in the UK. Here she reflects on her journey, why the role of nurses is becoming more relevant to HIV care every day, and how her new role at Gilead Sciences is allowing her to take on the challenge of HIV from a new perspective.

Q. Would you say HIV should still be considered a priority today, given treatment advances?

The past 20 years have been transformational in HIV and for many who lived and worked through the early HIV epidemic during the late 1980’s and early 1990’s (particularly healthcare professionals), the status quo is almost unrecognisable. Shows such as Channel 4’s recent hit ‘It’s a Sin’ have been a stark reminder of the realities that were faced in those early days. The perception today is often that we are in a position of comfort with HIV – where people are well managed and generally die with, not because of the virus. However, while there is much to be thankful for (and optimistic about), the reality is that HIV remains a deeply serious issue for many people. People living with HIV are getting older and frequently require coordinated, streamlined and joined up health management. Additionally, there are often a multitude of physical, psychological and social issues to consider for those living with HIV. There is a long way to go and a lot more to do in this area.

For specialist and practice nurses, HIV is still an issue that is important to be aware of. Over the next decade, shifts in the provision of care are likely to mean that their role will become increasingly central. Many people – from patients to our professional colleagues – will rely heavily on nurse expertise, proactivity, and support.

In short: yes, it is still absolutely something to consider widely important and I would say even a priority in many areas, particularly those where there have been missed HIV testing opportunities. We must not be complacent on HIV at a moment when we have an opportunity to end this epidemic for everyone, everywhere. My belief is that, working together, we absolutely can and must achieve that.

Q.How did HIV clinical management become a passion for you?

When I left school, I knew very little about HIV. My experiences had largely involved reading the news, general discussion, and films such as Tom Hanks’ Philadelphia (one of the first mainstream films to sensibly address the realities of HIV). Nobody really wanted to talk about it very much. I remember my religious studies teacher discussing it with us and opening my eyes somewhat, but I cannot say I entered nursing with the intention of moving into HIV management. As I began my studies and moved into nursing I began to see and learn more and more about HIV and AIDS. Quite frankly it was stark and, at times, very overwhelming. To see so many young people in such a critical state and often with no one by their side was just heart-breaking. Men in their 20s deteriorating and sadly passing away weighing 5 stone, with often only the staff caring for them, leaves a lifelong mark on you. But every loss made me more resolved to help and to be a positive force against this challenge.

I began my nursing career formally in 1995 at The University of Manchester where I qualified with a BNurs in nursing studies. My first HIV placement was in 1996, which was a pivotal time in HIV treatment and care. The advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy meant that there were – for the first time – medicines beginning to make a notable impact. As a nursing student that was quite thrilling, although at the time (and for many years afterwards) the regimens were incredibly complicated, and we were often finding our way with what was best for patients. Opportunistic infections and ever evolving changes to the virus meant that patient care at that time was often very challenging.

Following my studies, I joined the Chelsea and Westminster NHS Foundation Trust (the largest HIV unit in Western Europe). My nursing career progressed over the next few years, and I eventually became the first advanced nurse practitioner for HIV in the UK. Through this role I independently managed a large cohort of patients living with both clinically stable and more complex HIV disease.

Through this time, the clinical management of people living with HIV became my passion – and it is one that continues to this day. In particular, the clinical care and management of older adults living with HIV. I continued my studies and gained an MSc in advanced clinical practice in 2014, which allowed me to care for and prescribe for more clinically complex patients.

I remained at Chelsea and Westminster NHS Foundation Trust for 17 years, before starting a new role outside the NHS with Gilead, where I work today as National Market Access Senior Manager for HIV.

Q. What skills are important for nursing in HIV?

Through my professional development, I quickly recognised that caring for people living with HIV required empathy, no judgement, and the ability to really listen. I was struck early on by the fact that, as a nurse, you may well be the only person who that person talks to about their diagnosis. They may never disclose their status to anyone else, or what they think and feel about their HIV status – or the daily realities that they are facing. You are in a unique position to collect that insight and key to helping multi-disciplinary teams deliver the best care possible.

You also need to be proactive. Many people tend not to disclose what they perceive to be small issues. These may include things such as adherence to medication, seemingly trivial concerns over other health issues they have, or even challenges they may be facing around mental health, family issues or social stigma.

More often than not, patients are going through a lifelong care plan and there will be a complex web of challenges. Spotting the small warning signs early are where nurses can play a pivotal role – that can be lifechanging.

Q. What are the biggest challenges in HIV management today?

For me, the biggest challenges fall under three main categories:

- Comorbidity assessment and management

- The significant issue of stigma and inequality

- Assessment of medicine adherence

Comorbidities

Comorbidities are a big challenge. People with HIV are living longer, which is of course the goal. However, it means we are dealing with an ageing patient pool that will develop other conditions. Some of these may relate to their HIV management (or medication), others may be a result of growing older. This means that we need, as nurses, to properly understand the implications of comorbidity, the potential of drug-to-drug interactions and the early warning signs of when action needs to be taken.

This is where routine assessment is crucial. There is a longstanding concern in the field that so-called ‘stable patients’ (those who have undetectable HIV virus) may not be annually assessed for risk of comorbidities. This is generally because they are doing well and tend to spend less time in appointments and the clinic. However, it is crucial that all people living with HIV have annual routine assessment for issues such as mental health concerns, cardiovascular disease and fracture risk.

Nurses can play a central role in these assessments and screening for these comorbidities is second nature to primary care.

Usually, these assessments take place as part of routine check-ups within HIV services. However, it is becoming increasingly common for people living with HIV to be followed by GPs and practice nurses, and as part of that we will start to see a shift towards them having a key role in ensuring that these annual reviews and health checks take place.

With that in mind, it is integral that HIV and primary care services maintain a positive relationship with good communication to minimise duplication of efforts. Not only is it frustrating for the patients to undergo multiple assessments within a short timeframe, it is also important to protect valuable resource and time - especially at these times of high pressure on the NHS.

No matter which setting these tests are conducted in, it is then critical that these are shared with the other party and that any decision made with regard to managing any comorbidities is one that considers the wider holistic care of HIV.

Stigma and inequality

The second point on my list is the issue of stigma and the inequality that this so often fuels. There have been major awareness campaigns around HIV, as well as outstanding work by community organisations to dispel myths on the condition; however, many communities still bear the brunt of deeply embedded misperceptions. HIV ambassadors, the NHS, and industry are now working well together to try and support those impacted, but there is still a lot of social isolation and denial.

For people living with HIV within these communities, life can be tough. As a result, their care can be complex and extra considerations are often needed, such as greater vigilance of the need for mental health support.

Adherence

My last point is around the need for routine assessment of adherence. It is a practical reality that HIV is a condition where people will likely need to take medicines throughout their whole life. Granted, we are not in the position we were in during the 1990’s, where regimens were incredibly fiddly (for clinical teams, let alone patients) and patients had to juggle multiple medicines at different times of day with or without food etc. Things are thankfully more practical today; however, current regimens are not always straightforward and patients – particularly those with chaotic lifestyles – are still prone to adherence issues.

The U=U (undetectable = untransmittable) mindset has had a hugely positive and empowering impact for people living with HIV and partners, but it does demand that patients take medicine as prescribed. Resistance is still a reality and having an honest dialogue about adherence with patients is important. However, a natural thing for a patient to do is to downplay any lapses, or not mention them at all. Nurses therefore need to find positive, proactive ways of getting this information from patients.

One way to bridge these conversations is to ensure that any question around medicine adherence is as general as possible. Although sticking to the prescribed regimen of HIV medicine is critical, it is also hugely important that we do not differentiate between the importance of medicines or approach the topic in a way that would cause the patient to become defensive and close down.

While there is no expectation on nurses in primary care to manage non-adherence, the influential role that practice nurses have means they are able to normalise conversations about it, so that patients feel they are able to discuss when they have missed a dose. Of course, it is then integral that this information is passed directly to the HIV centre as soon as possible. Risk of resistance occurring with poor adherence is very significant, demonstrating the importance of cross-sector collaboration again.

Another reality is that proper assessment generally requires physically seeing HIV patients. The challenge is that physical appointments are gradually becoming more and more spread out, with weeks (sometimes months) without in-person interaction. And this may well become standard with the advent of long-acting antivirals for HIV now coming onto the scene. While it may seem preferable to see the patient just once in a while, for nurses we need to ensure we do not fall into the mindset of ‘out of sight out of mind’.

Q. What is your long-term vision for HIV and how are you working towards that now in your current role?

Moving from NHS to industry and my role at Gilead was a difficult decision but one I am absolutely convinced was the right one for me. I have always been passionate about clinical care in HIV and being on the frontline dealing with patients. While I am no longer on the frontline, my role at Gilead has allowed me the chance to keep working in the field I remain so passionate about, while still working collaboratively with the NHS on long-term collective goals.

In the long-term we are focusing on ending the HIV epidemic for everyone. Gilead has a deep heritage in supporting stigmatised communities and combatting inequality and in HIV this is really where our work stands out. The Gilead HIV Standards Support Team has already partnered with over half of UK HIV centres, positively impacting the lives of thousands of people impacted by this condition. Through these partnerships, we have been able to work with NHS teams to deliver improved outcomes in cardiovascular risk, stigma, health inequalities, bone health, variation in care for women and mental health.

We are also fully aligned to the NHS goal of zero HIV transmissions by 2030 in the UK. I do think this is achievable and it would be an enormous milestone. However, as I’ve said here, we also need to think about the many people who are living with it long term and what is best for them – practically and clinically. We are a way off from being able to talk about cure in HIV so the focus needs to be on transmissions, equity in care and supporting people to live well with HIV in as many ways we can.

Q. Are you optimistic given the challenges that remain?

I am very optimistic. Yes, persisting challenges remain, but it is heartening to consider how incredibly far we have come in HIV, both in terms of scientific innovation but also in shaping care and support for those affected. Tens of thousands of people have had their futures transformed as a result of people coming together for a common cause.

This is what I see working at Gilead every day. Passionate people who want to work with others to solve problems in HIV. We have a deep heritage in helping people who have faced stigma and discrimination and I believe we can continue to play a pivotal role in addressing struggling communities over the coming years.

My belief is that collaboration and partnership is critical. For years we have been working closely with experts from a diverse range of communities impacted by HIV to understand what people really need. This has allowed us to shape support programmes that are personal, practical and impactful.

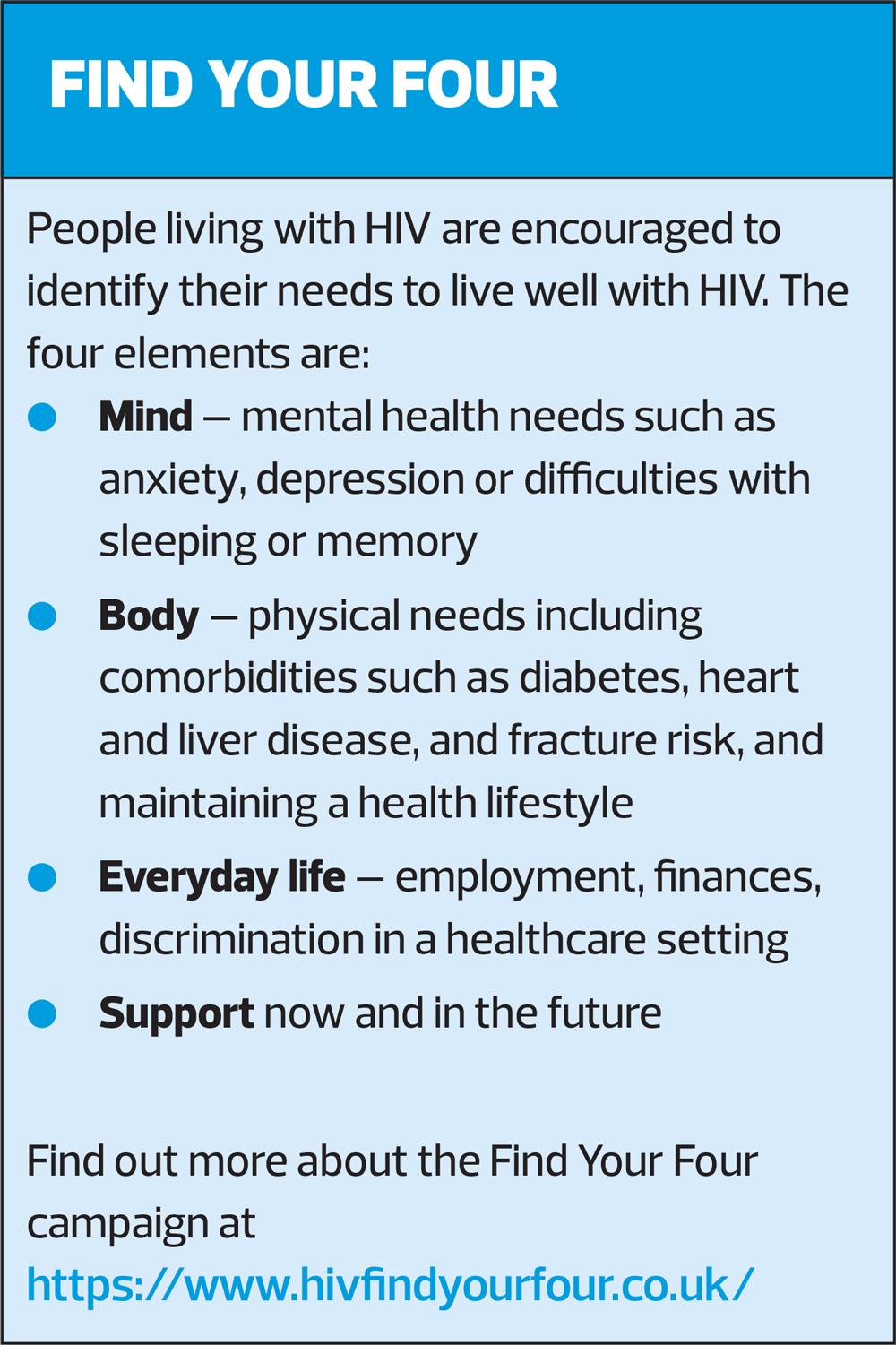

Just one example of this is Gilead’s Find Your Four campaign which has received exceptional support from experts across HIV. By developing culturally appropriate health education resources on HIV, we are helping people focus on the long-term health concerns that are important to them. There are many examples of outstanding work being done by Gilead and others, but this is one we are all proud of.

Q. What would be your advice to practice nurses seeking to know and learn more about HIV?

HIV can be a daunting and complex disease area for those clinicians who are not familiar to it. It can affect every system, and many clinicians are nervous that they may adversely impact the success of antiretroviral therapy if they ‘do the wrong thing’. However, from a clinical perspective, the majority of people living with HIV in the UK are doing incredibly well on treatment and their clinical needs are not dissimilar to others living and getting older with long-term chronic conditions.

It is highly likely that some practice nurses are already seeing people living with HIV in their clinics and those interested in improving their knowledge can access online courses such as the NHS Health Education England e-learning for health HIV and sexual health course, among others.

Lastly, talking to my patients was always one of my key ways of learning. People living with a long-term condition often know more about it than can ever be taught, so my advice is always be sure to listen to the patient sat in front of you.

Related articles

View all Articles