Long COVID – what should primary care be doing?

Beverley Bostock

Beverley Bostock

RGN MSc MA QN

Advanced Nurse Practitioner Gloucestershire

Education Facilitator Devon Training Hub

Practice Nurse 2020;50(8):12-15

There is growing evidence that the effects of COVID-19 infection may persist in the longer term, with symptoms continuing or recurring weeks after the initial acute illness. So what should we be doing about long COVID?

The coronavirus pandemic has resulted in high levels of mortality and morbidity. Unprecedented numbers of people have suffered from a range of symptoms resulting in them having to self-isolate at home to avoid infecting others, or being admitted to hospital. Those particularly vulnerable to the effects of the virus have been at risk of needing admission to intensive care units. Significant side effects including respiratory, vascular and renal complications have had an impact on recovery rates. However, it has only been relatively recently that the prolonged effects of the infection post-recovery have been recognised. Although it is still too soon for adequate good quality data to be available, the evidence for these long-term effects is increasing. This chronic COVID syndrome is now commonly being referred to as ‘long COVID’ and there is an increasing number of resources and guidelines being published to support people with long COVID, as well as for those caring for them.In this article we aim to:

- Identify key symptoms of long COVID

- Recognise interventions that may help people presenting with long COVID

- Highlight resources that can be used by healthcare workers and the public to support people with long COVID

The term long COVID refers to ongoing symptoms post coronavirus infection which include fatigue, cough, breathlessness, muscle and body aches,1 and which continue for more than four weeks after the original coronavirus infection.2 Other symptoms include an ongoing inability to smell and taste normally, low mood, skin rashes and gastrointestinal symptoms.3

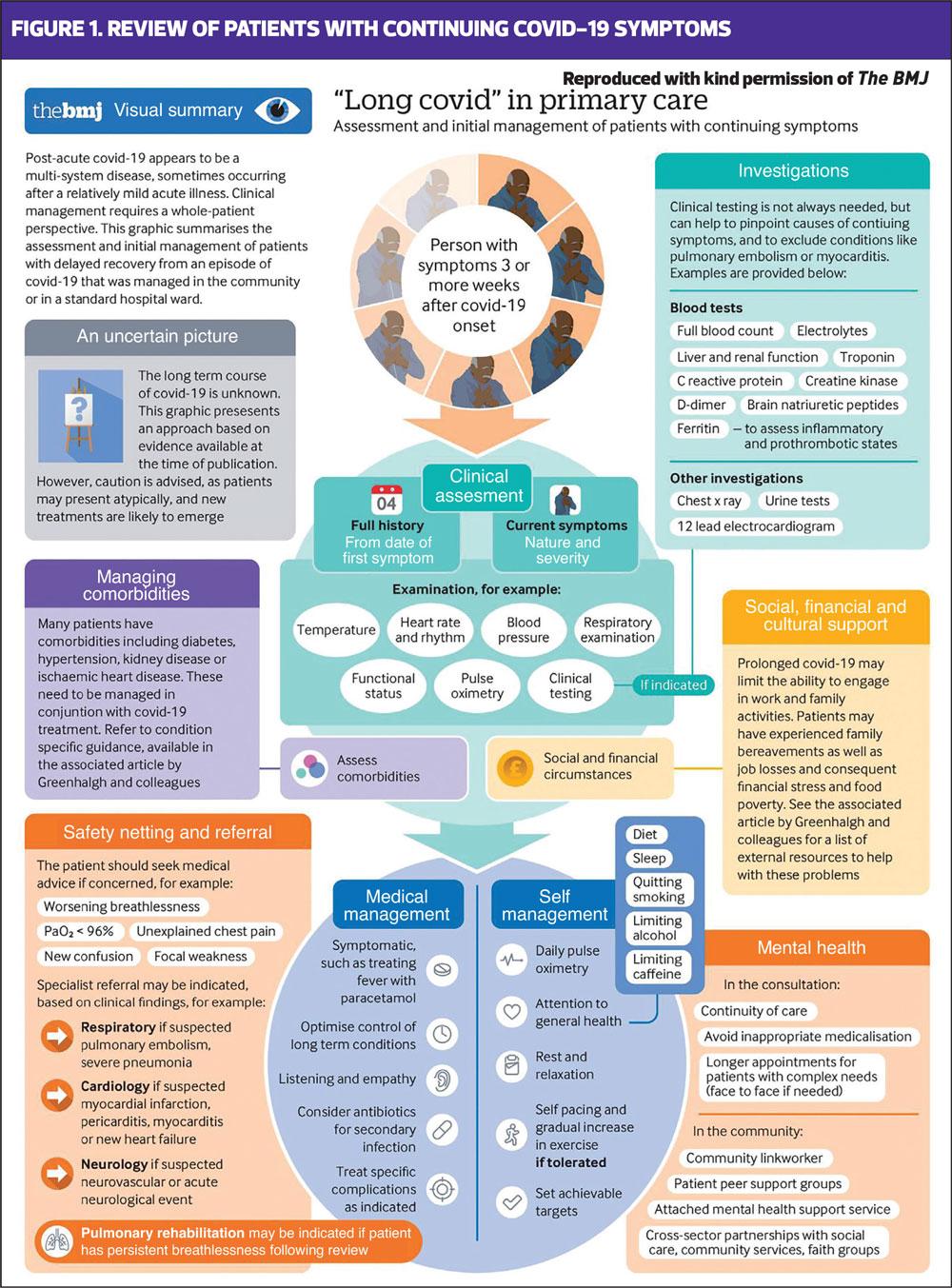

Recent guidance on the areas that should be addressed by primary care clinicians when reviewing people with long COVID has been published in The BMJ.2 This guidance offers clear and pragmatic advice to clinicians about what should be monitored and how patients can be supported (Figure 1).

General practice nurses (GPNs) are well placed to identify people who have had coronavirus and who may be suffering from long COVID, especially as many of those affected may never have been admitted to hospital and could be potentially overlooked. These individuals may not recognise what their symptoms are caused by, so it is essential that GPNs remain alert to the symptoms and ask about the possibility of a coronavirus infection prior to the onset of current symptoms. Even those who had a relatively mild coronavirus infection are at risk of long COVID, but they may not realise this to be the case.3 They also may never have had a coronavirus test, as people with mild symptoms were often advised to stay home and self-isolate before more widespread testing became available.

Post-infection, the symptoms described above are often recurrent, with people reporting that they start to feel better but that symptoms then recur. A paper by Marshall, published in Nature highlighted the ongoing and various symptoms experienced by many patients who have had coronavirus,4 and a report on patients in the United States showed that more than one in three of those infected had not returned to their previous level of health within 2-3 weeks.5 In another group of patients discharged from hospital in Italy post-COVID, 87% were still reporting at least one long-COVID symptom 60 days later and many were reporting a deterioration in their quality of life.6 People who have had coronavirus also seem to be at increased risk of developing long-term conditions such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes.3

MANAGING KEY SYMPTOMS OF LONG COVID

People with long COVID may have a range of symptoms and it may be difficult, if not impossible, to address all of them at once. A personalised approach should be taken, using shared decision-making around what matters most to that individual and which symptoms are having the greatest impact on their life. It is also important to recognise when input will be needed from the wider multi-disciplinary team and how that might impact on deciding what to focus on as a priority. Barker-Davies et al have said: ‘The sequelae in those who survive this illness will potentially dominate medical practice for years and rehabilitation medicine should be at the forefront of guiding care for the affected population.’7 The guidelines put together by Barker-Davies in recognition of this challenge can be a useful guide to supporting people on their long COVID journey.

Fatigue

Activity diaries can be useful when managing fatigue. They can be used initially to record patterns of fatigue and activities that lead to the highest levels of fatigue. This can help people to implement the ‘Plan, Pace, Prioritise’ approach to managing fatigue and this approach can be especially important where low mood is impacting on levels of tiredness and motivation.8 Chronic fatigue and low mood can be self-perpetuating, and using activity diaries to plan the day and record small successes over time can help in both respects. People should try not to focus on getting back to their pre-COVID energy levels and patterns of daily living but should work to a revised plan of doing a little more each week, as and when they feel able. Trying to get back to pre-COVID life too soon will only result in frustration and disappointment, and GPNs can help people to understand this and focus on what they are achieving, rather than dwelling on what they are not. These are some of the key principles that underpin cognitive behavioural therapy – recognising the need to change perspective to reflect the changes that need to happen to optimise recovery in long COVID.9 The Royal College of Occupational Therapists has produced some support materials for people recovering from COVID-19 who are suffering from fatigue and these can be downloaded and printed off or shared: https://www.rcot.co.uk/how-manage-post-viral-fatigue-after-covid-19-0. A key recommendation is that people with long COVID should reduce their exposure to coronavirus-related news and discussions and should focus on tools which support rest and relaxation.

Cough and breathlessness

Asthma UK and the British Lung Foundation have both come together to develop a resource to support people with cough and dyspnoea post COVID.10 There is also a section for healthcare professionals to get more information on their role in helping people with long COVID respiratory symptoms. This ‘Post-COVID Hub’ explains that respiratory symptoms are common for people who have had coronavirus and may range from the most severe (acute respiratory distress syndrome) to the mild but persistent, such as cough or breathlessness on exertion. The resources are split up into three sections: one for those who stayed at home when they were infected, another for people who were admitted to hospital and another for those who required intensive care. Respiratory symptoms are separated up into dyspnoea, problems with sputum and persistent cough. Examples of the advice given include breathing exercises for breathlessness, using the active cycle of breathing to help clear the chest and sipping drinks or sucking boiled sweets for chronic cough. Several of the links on the Post COVID Hub connect to the www.yourcovidrecovery.nhs.uk website, ensuring that the same messages are repeated and conflicting advice is avoided, even when there is limited evidence available.

Myalgia and headaches

Many people complain of musculoskeletal symptoms in both the acute and long COVID phases of the condition. The mechanism for this is unclear, although many viral conditions include joint and muscle pain as a feature.11 In children who have had COVID, paediatric inflammatory multisystemic syndrome has been reported – a collection of symptoms which includes Kawasaki-like disease, Kawasaki disease shock syndrome, toxic shock syndrome, myocarditis and macrophage activation syndrome.12 In general, the advice is to pace activities but to get back to using muscles and joints which may have been underactive during the acute illness phase. Physiotherapy may also help. Analgesia may be useful for musculoskeletal pain and headaches, but care should be taken not to overmedicate. Topical treatments may be useful in some cases. Codeine may add to feelings of drowsiness and nausea, both of which can be long COVID symptoms.

Mental health issues

Mental health problems including depression, anxiety and cognitive difficulties have been reported in people with long COVID.3 If these symptoms are reported, using a formal mood assessment tool (PHQ9 or the GADS test) may help to identify whether the patient is suffering from clinical depression or anxiety. Previous viral outbreaks such as SARS were associated with an increase in the prevalence of depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder; however, data on people with COVID-19 are incomplete, so caution should be exercised when assuming that the impact will be the same.13 If someone does appear to have a significant depression and/or anxiety score, however, then it would be appropriate to consider referral to a mental health specialist for ongoing support. The British Psychological Society also has a range of support materials for healthcare professionals who are helping people with long COVID. These are available from https://www.bps.org.uk/coronavirus-resources/professional.

Long term conditions

Cardiovascular complications have been reported post COVID. Coronavirus seems to bring about a pro-thrombotic and inflammatory state which will worsen the low grade systemic inflammation that is often present in people with risk factors for cardiovascular disease and diabetes.14 This addition of insult to injury means people with or at risk of cardiovascular disease are more likely to have a more severe COVID-19 illness and suffer from long-term complications such as acute myocarditis, heart failure and thromboembolic disease.3 People who complain of cardiovascular symptoms post COVID should undergo careful assessment and appropriate management. Of interest, early anecdotal reports suggest that people taking statins, ACE inhibitors and anticoagulants might have had better outcomes than those who were not when they contracted the virus.14 As with much of what we ‘know’ about coronavirus, however, the evidence is actually sparse, and anecdote should not replace good quality research.

Kidney and liver impairment

Acute coronavirus infection may be associated with an increased risk of acute kidney injury.3 People who have been found to be renally impaired while unwell will need ongoing monitoring to assess for recovering or deteriorating kidney function. Those people who have not been admitted may not have had any renal function tests, so it is important to consider requesting them if the individual is complaining of long COVID symptoms. Renal impairment may be associated with malaise, breathlessness and anaemia in severe cases and these symptoms should not be put down to long COVID until other causes have been excluded. Liver function can be adversely affected by viral infections but current reports suggest this may be temporary.15 However, ongoing monitoring may be needed.

Lungs

Lung inflammation, pulmonary fibrosis and pulmonary vascular disease have all been reported in people with coronavirus.3 Assessment of lung function is important in order to determine the cause of ongoing respiratory symptoms, but GPNs should also be mindful of infection risk when carrying out peak flow readings, spirometry and FeNO testing. Recent guidance from the Association of Respiratory Technicians and Physiologists has said that these procedures can be reintroduced, but many CCGs are advising nurses to postpone testing as the logistics of performing these tests are complex.16 Home spirometry using the Spirobank Smart may be an option but many believe that diagnostic hubs are the way forward. At the moment, there is little evidence for the pharmacological management of long COVID respiratory symptoms and the focus is on breathing exercises as discussed above. In people with pre-existing respiratory disease the importance of regular inhaled therapy should be stressed, and review of inhaler technique should be a priority as any change in lung function may mean that a change of device is required.

Diabetes

Long COVID may affect diabetes risk and management in many ways. Bornstein et al have identified an increase in poor control in people with diabetes which may relate to the virus, the treatment and changes in lifestyle in people who are tired, unable to exercise and possibly comfort eating.14 Furthermore, the virus appears to make people more insulin-resistant and so people with pre-diabetes may now present with full-blown type 2 diabetes. Viruses are recognised as a trigger for type 1 diabetes too and the Bornstein paper highlights this concern.14 GPNs should be aware of the symptoms of type 1 and type 2 diabetes in this specific group of people and should not hesitate to test, diagnose and manage appropriately. Individuals should be encouraged to engage in gentle and gradual lifestyle changes to improve outcomes and reduce risk.

APPROACHES TO MANAGING LONG COVID SUPPORT IN PRIMARY CARE

In response to the growing evidence that people were suffering from ongoing symptoms after recovering from the acute phase of COVID-19, the NHS has established a website aimed at supporting people on the road to recovery. The website is available at https://www.yourcovidrecovery.nhs.uk/. Content includes advice on recovering from the virus, with a particular focus on mental health issues such as managing fear, anxiety and low mood. In addition, people with symptoms of long COVID will be able to access other forms of help following an individual assessment of their needs. This will include individual face-to-face consultation with a rehabilitation team based locally and made up of physiotherapists, nurses and mental health specialists. Following assessment, there will be a range of services available, including a personalised package of online or telephone-based care for up to three months, exercise programmes, mental health referrals and information about joining peer support communities for those who would like to do so.

SUMMARY

People who have had COVID-19 are considered to have long COVID if they suffer from symptoms that last longer than 3 weeks after the acute infection. The severity of the original infection does not seem to dictate the likelihood of getting long COVID, so GPNs should consider this diagnosis in people who have had (or suspect they may have had) coronavirus. Symptoms include cough, breathlessness, muscle aches and headaches, fatigue and mental health problems, amongst others. GPNs should consider other causes for these symptoms, such as chronic kidney disease or pulmonary fibrosis, which may or may not be related to coronavirus. Although good evidence and trial data are lacking at this time, there are resources and interventions which can help people to recover. One of the most important things that a GPN can do is to ask about symptoms, listen to people who continue to feel unwell and offer support and advice, especially for those who have had milder infections and who may feel that they are overlooked.

REFERENCES

1. Nabavi N. Long covid: How to define it and how to manage it. BMJ 2020;370:m3489 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3489

2. Greenhalgh T, Knight M, A’Court C, et al. Management of post-acute covid-19 in primary care BMJ 2020;370:m3026 https://www.bmj.com/content/370/bmj.m3026

3. Public Health England. COVID-19: long-term health effects; 2020. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-long-term-health-effects/covid-19-long-term-health-effects

4. Marshall M. The lasting misery of coronavirus longhaulers. Nature 202;585 339-341 https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-020-02598-6

5. Tenforde MW, Kim SS, Lindsell CJ, et al. Symptom duration and risk factors for delayed return to usual health among outpatients with COVID-19 in a Multistate Health Care Systems Network - United States, March-June 2020. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report 2020;69(30):993–998. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6930e1

6. Carfì A, Bernabei R, Landi F, for the Gemelli Against COVID-19 Post-Acute Care Study Group. Persistent Symptoms in Patients After Acute COVID-19. JAMA 2020;324(6):603–605. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.12603

7. Barker-Davies RM, O'Sullivan O, Senaratne K, et al. The Stanford Hall consensus statement for post-COVID-19 rehabilitation. British journal of sports medicine 2020;54(16):949–959. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102596

8. Royal College of Occupational Therapists. Recovering from COVID-19: Post viral-fatigue and conserving energy; 2020. https://www.rcot.co.uk/recovering-covid-19-post-viral-fatigue-and-conserving-energy

9. NHS. Cognitive behavioural therapy; 2019 https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/cognitive-behavioural-therapy-cbt/

10. Asthma UK & British Lung Foundation. Post Covid Hub; 2020 https://www.post-covid.org.uk/

11. Kucuk A, Cumhur Cure M, Cure E. Can COVID-19 cause myalgia with a completely different mechanism? A hypothesis. Clinical rheumatology, 2020;39(7):2103–2104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-020-05178-1

12. Galeotti C, Bayry J. Autoimmune and inflammatory diseases following COVID-19. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2020;16:413–414 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41584-020-0448-7

13. Rogers JP, Chesney E, Oliver D, et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic Lancet Psychiatry 2020;7:611–27 https://doi.org/10.1016/ S2215-0366(20)30203-0

14. Bornstein SR, Dalan R, Hopkins D, et al. Endocrine and metabolic link to coronavirus infection. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2020;16:297–298 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41574-020-0353-9

15. Ghoda A, Ghoda M. Liver Injury in COVID-19 Infection: A Systematic Review. Cureus 2020;12(7): e9487. doi:10.7759/cureus.9487

16. Association for Respiratory Technology & Physiology. ARTP Guidance – Respiratory Function Testing; 2020.

17. Phillips M, Turner-Stokes L, Wade D, Walton K. Rehabilitation in the wake of Covid-19 – A phoenix from the ashes. British Society of Rehabilitation Medicine (BSRM); 2020. https://www.bsrm.org.uk/downloads/covid-19bsrmissue1-published-27-4-2020.pdf

18. Royal College of Occupational Therapists. Rehabilitation; 2020. https://www.rcot.co.uk/node/3474 ?

Related articles

View all Articles