An update on tuberculosis

Helen Thuraisingam

Helen Thuraisingam

RGN MSc (Advanced Practice)

Clinical Nurse Manager/Lead Nurse, Leicester, Leicestershire & Rutland TB Nursing Service University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust

Practice Nurse 2020;50(7):35-40

While COVID-19 has, rightly, been the focus of attention, TB is an infectious disease that has been present for millennia, often gets forgotten yet still kills many people. Primary care has an important role in the control and management of this curable and preventable disease

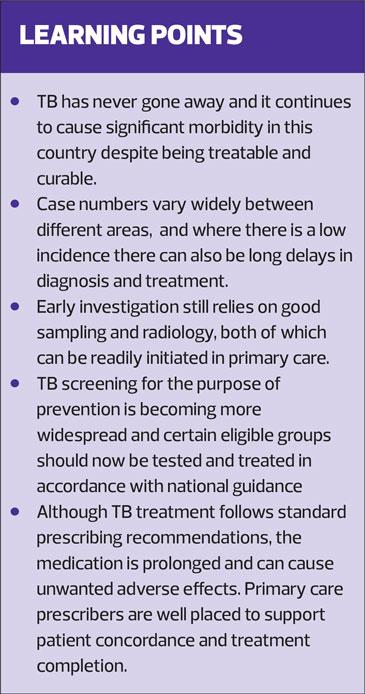

With the emergence of new and previously unknown life-threatening infectious diseases, we have all become more aware of the impact that infectious disease transmission has on individuals, and of its effects on society. Mycobacterium tuberculosis has perfected the art of survival. It has persisted in human communities for thousands of years. In 2018, an estimated 10 million people fell ill with tuberculosis (TB) and it was responsible for the deaths of 1.5 million people globally, currently more than have died of COVID-19. There were cases in all countries and in all age groups,1 and all countries, except those in Western Europe, North America, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, have an increased risk from TB. But, unlike COVID-19 at present, TB is curable and preventable.

In the UK, at the start of the 20th century, improvements in public health and the availability of antibiotic treatments resulted in falling rates of TB. However, rates continued to increase during the 1980s and 1990s. TB cases in England peaked at 8,280 in 2011. Since then, following a concerted public health effort, the number of notified TB cases has fallen by nearly 40% to 4,655 in 2018.2 However, the proportion of people who have multi-drug resistant TB has not declined and TB remains prevalent in cities, with London having the highest rates.

TB continues to present a serious threat to public health in the UK. TB rates in England remain among the highest in Western Europe. Provisional data for 2019 suggest that TB case notifications in England have stablised since 2018,2 although, clearly it continues to be important to focus on public health initiatives to improve TB control and to maintain and extend the downward trend in TB incidence. We need to ensure that areas that already have a low incidence are able to reduce their incidence even further.

Surveillance data demonstrate that the proportion of people who experience a delay between symptom onset and diagnosis remains stubbornly high. Almost one third of pulmonary cases in 2018 experienced a delay of more than 4 months before starting treatment. A key objective is to promote more rapid diagnosis and reduce delays in access to specialist investigation, care and treatment. Primary care clinicians have an essential role in knowing which groups of people are at increased risk of TB and in maintaining an awareness of the signs and symptoms that will trigger appropriate investigations and referral. This article discusses primary care aspects of the control and management of TB with particular emphasis on rapid differential diagnosis and the role of primary care in TB control.

TRANSMISSION AND PATHOLOGY

The most common route of infection with TB occurs through inhalation of aerosolised Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria. The bacteria are transmitted from person to person when tubercule bacilli are released by an infectious person through coughing. Airborne particles may also be produced when talking, sneezing, shouting or singing. The conditions in which TB can be spread are the same as for COVID-19.

A susceptible person becomes infected as a result of inhaling small infectious droplet nuclei deep into the alveoli. And, just like COVID-19, the risk of inhalation can depend on the environment. Confined spaces with poor ventilation are associated with an increased risk of infection and, historically, overcrowding, reduced air exchange and limited sunlight are thought to contribute as the bacilli are killed by ultraviolet radiation.3 TB is a multisystem disease and can affect any organ of the body, however pulmonary tuberculosis is the most frequent site of involvement and it is usually only pulmonary TB that is infectious.

The initial host contact with mycobacterium leads to primary tuberculosis. This primary infection is usually localised to the middle portion of the lungs and is known as the Ghon focus. In most people, the Ghon focus enters a state of latency known as latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI). In this state it does not cause symptoms but is capable of being reactivated. Most individuals with LTBI will be unaware of its existence for long periods of time (usually years) after the initial primary infection. However, a small proportion of people can develop active disease following the first exposure. This primary progressive tuberculosis is most commonly seen in children, people with immunosuppression and the malnourished.

It has been demonstrated that about 30% of healthy individuals closely exposed to TB will become infected; of those 5%-10% will go on to develop active disease.4 In addition to inhalation, tuberculosis may also be transmitted by ingestion (particularly M. bovis in milk) or by accidental inoculation through the skin.

SCREENING TESTS

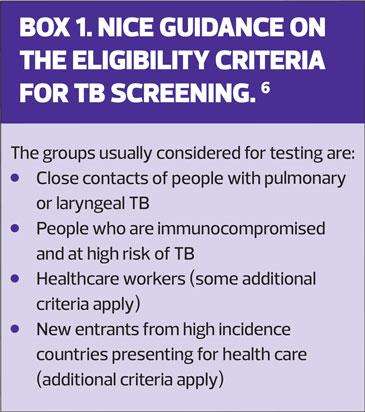

Two screening tests are most commonly used, the Interferon Gamma Release Assays (IGRA blood tests) and the Mantoux tuberculin skin test (purified protein derivative [PPD]). Both these tests indicate exposure or latent tuberculosis. Referral for further investigations should be performed in the presence of a positive result and it is necessary to exclude active TB disease before considering prophylactic treatment for LTBI.5 NICE has issued guidance on the eligibility criteria for TB screening tests.6 (Box 1)

A positive screening test indicates exposure to tuberculosis and a risk of developing active TB in the future. Screening tests are not reliable methods of investigating those with symptoms when active TB disease is suspected, and false negative screening results can occur in people who are immunocompromised, especially with HIV.

RISK FACTORS

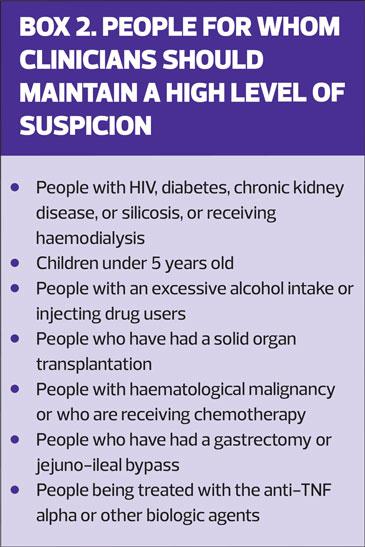

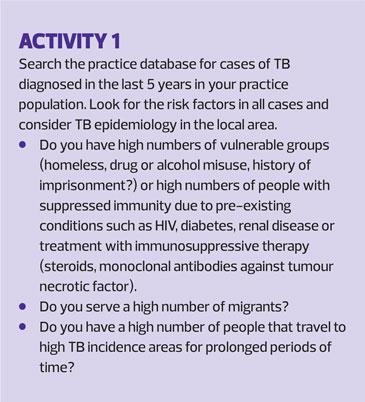

TB can occur in anyone without the presence of other risk factors. TB cases and deaths are highest in resource-poor countries, and the risk of developing active TB is highest immediately after initial infection and rises dramatically in individuals with compromised immune systems. There are specific groups of people with clinical conditions in whom the risk of LTBI becoming active is increased.6 (Box 2)

In primary care, the management of patients with long-term and underlying chronic health conditions means that it is important to understand and recognise the additional medical susceptibility to develop TB. Malnutrition, indoor air pollution, excessive alcohol consumption, and smoking are other recognised risk factors for TB.

Although anyone can get TB, it continues to be a disease associated with social inequalities. In England, specific groups have been identified, where key areas for action are aimed at improving the understanding of the health needs of these populations with TB. The specific groups where additional support is recommended are:

- Some migrant groups

- People in contact with the criminal justice system

- People who misuse drugs and/or alcohol

- People with mental health needs

- People who are homeless.

(See Activity 1)

In many areas, partnership working is a key element to better meeting the needs of these groups. Local governments have a public health role and can be instrumental in supporting the social and economic factors that are essential in controlling TB. Housing, immigration and probation services can all facilitate healthcare to achieve improved treatment outcomes. In addition, general practice staff will often have strong relationships with patients in these groups and may already work in liaison with other statutory and voluntary sector workers to support care delivery.

SYMPTOMS

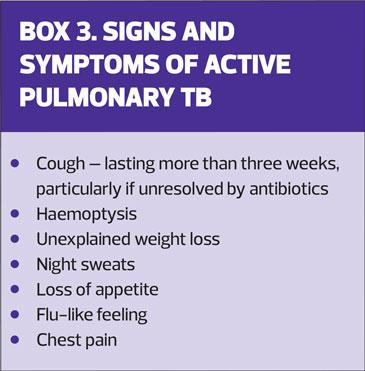

Pulmonary TB should be suspected in anyone with an unexplained cough that lasts more than three weeks, especially if other symptoms or risk factors are also present. (Box 3)

Diagnosing active TB can, however, be far from straightforward. Patients who develop active disease often have generalised, non-specific symptoms, such as lack of appetite, weight loss, fatigue, and fever. TB commonly mimics other systemic disorders including:

- Pneumonia

- Malignancy

- Non-tuberculous mycobacterium

- Fungal infections

- Sarcoidosis.

Because the signs and symptoms of tuberculosis can be indistinguishable from those associated with other diseases, in areas of the country where tuberculosis is less common this can lead to serious delays in diagnosis, and sometimes death.

INVESTIGATION AND DIAGNOSIS

A diagnosis is usually reached using a combination of clinical examination, investigations and laboratory tests.

When pulmonary TB is suspected an urgent chest X-ray should be obtained and sputum samples collected if possible. Non-pulmonary TB symptoms can be specific to the organ or system affected, such as bone pain, meningeal infection or enlarged lymph node swellings. Individuals with LTBI and subclinical disease are asymptomatic.

Chest X-ray

Although chest X-ray is a very sensitive tool for detecting pulmonary lesions, it is not always a very specific test since even large lung cavities may be suggestive of other pulmonary pathology, for example lung cancer. In addition, chest X-rays may be particularly difficult to interpret in HIV-infected people.

Sputum smear test

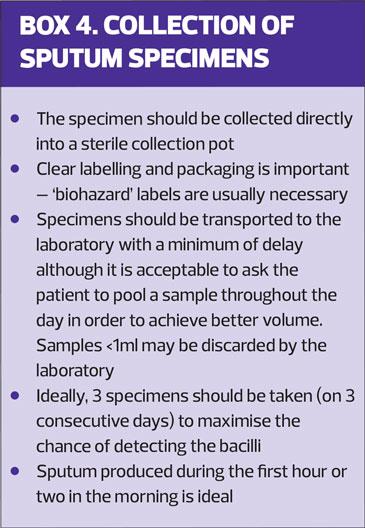

The bacteriological investigation of tuberculosis is the only certain way of confirming a diagnosis. This is performed by the microbiological detection of tubercule bacillus, usually from a sputum specimen. The most frequent test is the examination of sputum smears after staining for acid-fast bacilli (AFB). Sputum microscopy is critical in identifying infectious patients and therefore in the overall control of TB. Nurses working in all settings have a key role in ensuring that high quality specimens are taken. (Box 4)

It has been estimated that, of patients eventually found to be sputum smear positive, 80% - 90% are diagnosed on the first sputum specimen.7 In most areas, a smear result should be available within 48 hours. Sputum sampling remains the key to diagnosis and is easy to obtain. Its wider use in primary care should be promoted.

Microbiological culture and sensitivity

Microbiology cultures provide a more reliable result than smear examination but it can take several weeks for results to become available. However, TB cultures are required to confirm the diagnosis bacteriologically and provide essential information about drug sensitivities.

Where sputum is not readily available, fibre optic bronchoscopy may be used to obtain bronchial washings or biopsies. Specimens can also be obtained for histological examination. In children, gastric washings can be very effective, since children usually swallow their respiratory secretions. If extra-pulmonary TB is suspected more invasive sampling methods are usually required. Renal tuberculosis is usually diagnosed from specimens of urine. Other specimens that can be used for bacteriological examination include pleural biopsies or fine-needle aspirates of tissue or exudates.

Although culture results may take several weeks to become available using traditional methods, due to the slow-growing nature of mycobacteria, rapid bacteriological methods such as Nuclear Amplification and gene-based tests are now also available, including whole genome sequencing (WGS). WGS is the determination of the sequence of most of the DNA content comprising the entire genome of the mycobacteria. It can help in understanding the molecular relationships between different mycobacteria isolates and it can inform the investigation of potential transmission events and their early detection.8

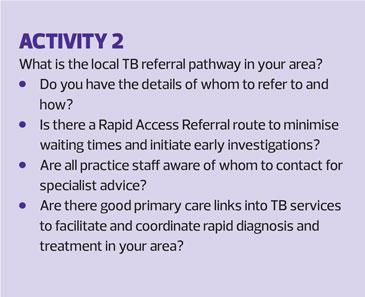

REFERRAL

Although most patients do not require hospital admission to be commenced on TB treatment, physicians with specialist knowledge and experience should be responsible for overseeing the care of TB patients. They may be either Respiratory or Infectious Disease physicians and all areas of the country will have access to a specialist TB team. TB services will also have established liaison with public health laboratory services and specialist MDT advice. In addition, all TB treatment is provided free of charge for everyone from TB clinics (irrespective of eligibility for other NHS care).9 (See Activity 2)

TB is a notifiable disease

Clinicians have a statutory duty to notify either local authorities or Public Health England of suspected cases.

Notifications in England and Wales are made to the Proper Officer of the local authority; local authorities are required to appoint such officers, usually the local consultant in Health Protection. Notification is intended to support surveillance, to detect potential outbreaks and it ensures that contact tracing occurs in order to find people at risk of exposure.

In practice, notification is usually performed by the treating physician. If a primary care health professional has referred someone for TB investigations or treatment it is useful to liaise with local TB services or Public Health colleagues as this will often provide initial helpful reassurance to individuals, families and workplaces about risk assessments and procedures for contact tracing.

TREATMENT AND MONITORING

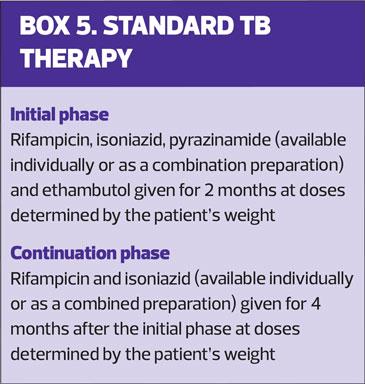

TB treatment is standardised (Box 5). UK Guidelines,6 recommend that all new TB patients start on quadruple therapy. Treatment is a 6 month regime in two phases consisting of:

- Initial phase treatment with 4 agents for 2 months, and

- Continuation phase treatment of 2 agents for 4 months.10

For people with evidence of LTBI who fulfil the eligibility criteria, one of the following chemo-prophylactic drug treatments may be offered to reduce the risk of active disease developing in the future:

- 3 months of isoniazid (with pyridoxine) and rifampicin, or

- 6 months of isoniazid (with pyridoxine).

Weight monitoring occurs throughout treatment. Drug resistance can be caused by under-dosing of anti-tuberculosis medication and if there is any doubt specialist advice should be sought regarding the regime. Pyridoxine (Vitamin B6) is normally given to patients on isoniazid as prophylaxis against peripheral neuropathy.

Standard and enhanced case management is overseen by a case manager who will usually be a specialist TB nurse or (in low-incidence areas) a nurse with responsibilities that include TB, depending on the patient’s circumstances and needs. Adherence to appropriate drug treatment is a major determinant of treatment success and one of the most important aspects of TB treatment is close monitoring and support. Poor adherence to treatment leads to treatment failure and contributes to the development of drug resistance.11

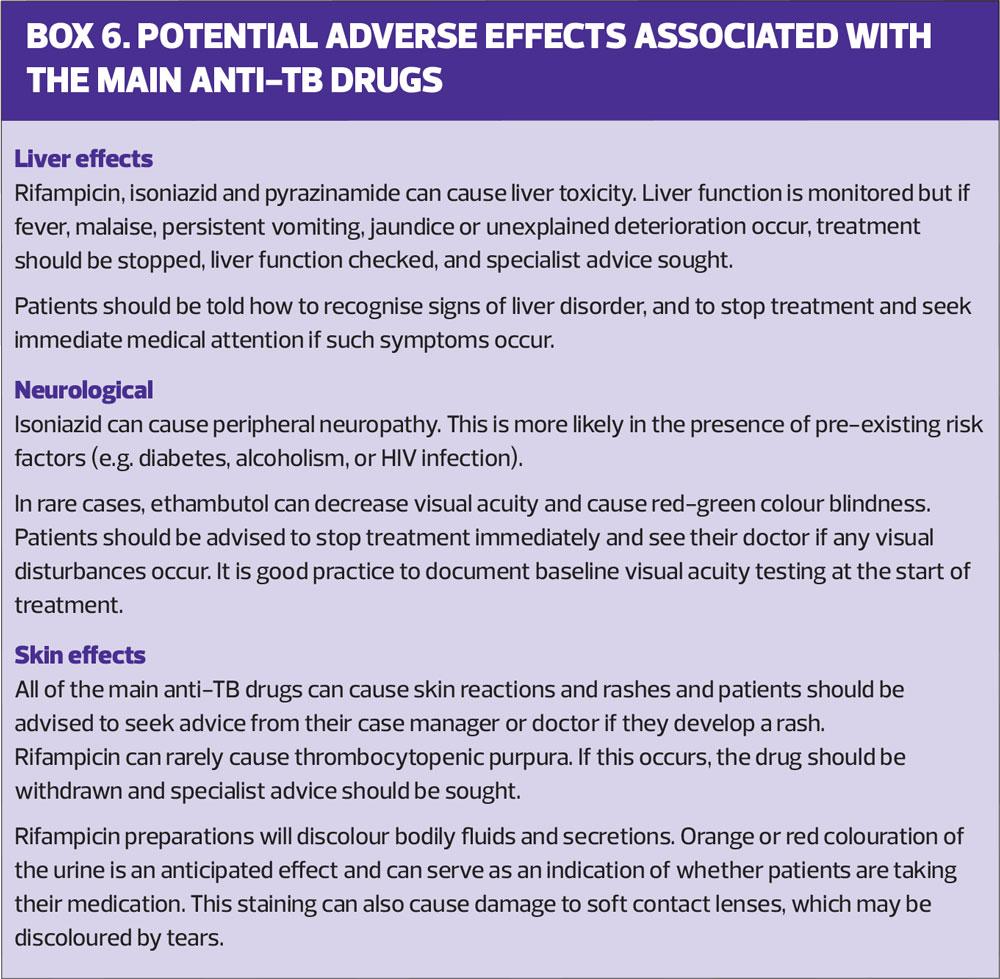

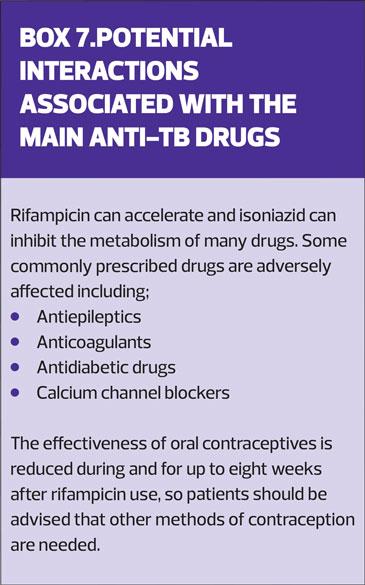

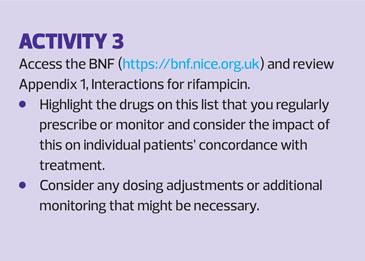

All anti-TB drugs can cause adverse side effects (Box 6) and there are a number of important potential drug interactions (Box 7). For primary care health professionals an awareness of these and knowledge of the necessary patient counselling and management can significantly support treatment adherence.

Anyone prescribing for a patient on TB medication must consider the implications of potential drug interactions for individual patients. It is advisable to consult the British National Formulary (BNF) and summaries of product characteristics for each drug if adjusting any other concurrent medication (See Activity 3).

DRUG RESISTANCE

As with all antibiotic treatments, there is increasing concern about drug resistance. According to surveillance data for England,2 the number of people in the drug resistant cohort has been continuously decreasing since a peak of 95 people in 2011. However, the proportion of all cases has remained fairly constant.

First-line drug resistance is defined as resistance to at least 1 of the first line drugs (isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol or pyrazinamide). In 2018 in England, 11.4% of people had resistance to at least 1 first line drug, and 1.2% had multi-drug resistance (MDR-TB), i.e. resistance to at least isoniazid and rifampicin, with or without resistance to other drugs.

Extensively Drug Resistant TB (XDR-TB) is defined as resistance to isoniazid and rifampicin (MDR-TB), at least 1 injectable agent (capreomycin, kanamycin or amikacin) and at least 1 fluoroquinolone (moxifloxacin, ofloxacin, ciprofloxacin). The number of cases in England with initial XDR-TB remains very low, but globally it is an increasing problem.11

The treatment of drug-resistant TB is more complex and prolonged than standard treatment. Medication may be required for up to 24 months or more, depending on drug resistance profiles, HIV status and tolerance of the MDR-TB/XDR-TB regimen. Patients with infectious multi-drug-resistant TB should always be admitted to hospital and isolated in a negative pressure room until they are no longer infectious, and all treatment should be fully supervised, whether as an inpatient or outpatient.

It has been estimated that the cost of managing a case of pulmonary MDR-TB may be 10 to 50 times higher than the cost of managing a fully sensitive case.12 Regardless of the cost, the drug regimen can have potentially profound adverse side-effects, and it is imperative that the risks of resistance developing are minimised by encouraging all TB patients to adhere to their drug regimens.13

CONCLUSION

Knowledge of TB epidemiology, investigation, treatment and control continues to be essential for primary care health professionals. Although treatment is initiated and supervised by specialist multi-disciplinary teams, primary care colleagues have critical roles in its early detection and investigation and an important contribution to make in supporting patients and their families to prevent the spread of disease and the development of drug resistance.

The COVID-19 pandemic will impact on the control of all infectious disease, including TB. Missed diagnosis and treatment of TB will increase the numbers of undetected and unreported cases of both active disease and latent infection. This will contribute to morbidity and mortality and fuel an increase in disease transmission. However, with a coordinated, collaborative care approach, TB is both preventable and curable.

REFERENCES

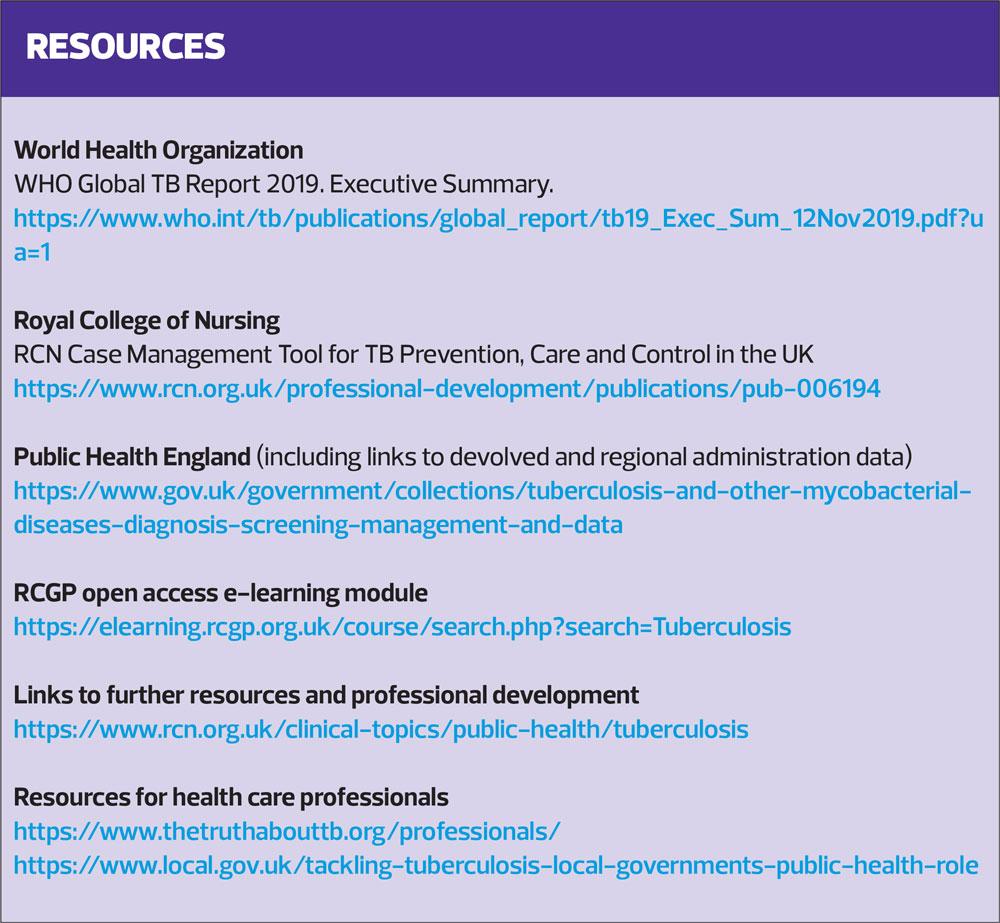

1. World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2019. https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/

2. Public Health England. Tuberculosis Unit, National Infection Service. Tuberculosis in England 2019 report. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/821334/Tuberculosis_in_England-annual_report_2019.pdf

3. Pratt JP, Grange MP, Williams VG. Tuberculosis: A Foundation for Nursing & Healthcare Practice. London: Hodder Arnold; 2005.

4. Davies PD, Barnes P, Gordon S. Eds. 5th Edition. Clinical Tuberculosis. London: CRC Press; 2014.

5. Public Health England. Tuberculosis Unit, National Infection Service. Latent TB infection testing and treatment programme. Technical guidance and specification. London. Public Health England. 2019.

6. NICE NG33. Tuberculosis; 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng33

7. World Health Organization. Early detection of tuberculosis. An overview of approaches, guidelines and tools; 2011. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/70824/WHO_HTM_STB_PSI_2011.21_

8. Public Health England & NHS England. Collaborative TB Strategy for England. 2015. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/403231/Collaborative_TB_Strategy_for_England_2015_2020_.pdf

9. Royal College of Nursing. A Case Management Tool for TB Prevention, Care and Control in the UK. Clinical Professional Resource; 2019. https://www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/publications/pub-006194

10. Joint Formulary Committee. British National Formulary (online) 2020. London. BMJ Group and Pharmaceutical Press. http://www.medicinescomplete.com

11. World Health Organization. Rapid Communication: key changes to treatment of multidrug and rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis (MDR/RR-TB); 2019. https://www.who.int/tb/publications/2018/rapid_communications_MDR/en/

12. Loddenkemper R, Sotgiu G, Mitnick C. Cost of tuberculosis in the era of multidrug resistance: will it become unaffordable? Eur Respir J 2012;40:9-11

13. Tiberi S, Muñoz-Torrico M, Duarte R, et al. New drugs and perspectives for new anti-tuberculosis regimens. Pulmonology 2018; 24(2):86?98.

Related articles

View all Articles