What can be done to improve vaccination uptake?

Mandy Galloway

Mandy Galloway

Editor

While the interim report of the Vaccinations and Immunisations Review focuses largely on contractual issues and addressing accessibility, the problem of vaccine hesitancy runs deeper than whether appointments are convenient

Immunisation and vaccination is one of the most powerful public health weapons to reduce preventable illnesses and deaths. But while coverage for most vaccines – especially primary courses of childhood immunisations – is high, there has been a steady decline in uptake in recent years.1

Dropping below the World Health Organization’s 95% target means that the coverage in the UK is no longer sufficient to confer herd immunity or to prevent onwards transmissions of infections, particularly measles.1 One-in-seven 5-year-olds have yet to be fully immunised against measles, mumps and rubella, rising to one-in-four children in London. One-in-eight children starting school still need their 4-in-1 preschool booster.2

In England alone, 301 new measles infections were confirmed in the three months to June 2019, compared with 231 in the first quarter of 2019. The rise comes after several years when no more than a handful of cases were reported.3

One result of this is that in September this year, the WHO withdrew the UK’s ‘measles-free’ status.

Take up of one dose of MMR vaccine by 5 years is 94.5%. Uptake for the second dose by age 5 is 86.4% (down from 87.2% in 2017-18), and uptake for the DTaP-IPV/Hib vaccine at 12 months is 92.1%, its lowest since 2008-09.4

But the national picture glosses over local variations. According to a report in The Guardian, the uptake statistics for the Leatside area of Totnes, Devon – ‘a haven for people seeking an alternative lifestyle’ – is just 78% for MMR, and 84% for DTaP-IPV/Hib.5

Exemplifying the reasons for the low uptake, Vince and Daisy (not their real names), who run a successful eco-business in Totnes, said they didn’t mind if people thought of them as ‘wackos’ for not vaccinating their two young children. ‘The media portray it as a hippy movement but it’s not, it’s an educated choice for many people here,’ said Daisy. ‘We spent months reading medical articles, speaking to parents of vaccine-injured children. Our human body can defend itself. We’re weakening ourselves if we vaccinate.’5

According to Public Health England (PHE) only 9% of parents have seen, read or heard about something that would make them doubt having their child immunised – down from a third (33%) in 2002.6

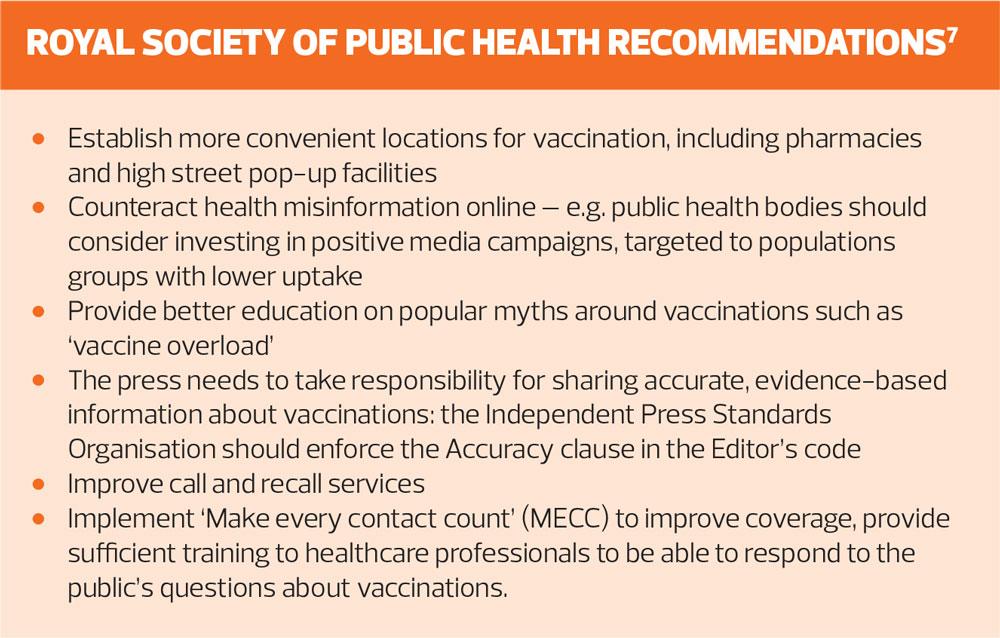

However, a survey by the Royal Society for Public Health (RSPH) reported that 40% of parents were often or sometimes exposed to negative messages on social media about vaccination, rising to 50% of parents of children under 5 years.7 Over a quarter of people (28%) believe, incorrectly, that ‘you can have too many vaccinations’, and understanding of the concept of herd immunity was low.7

‘In a world where misinformation is so easily spread online we must all speak confidently about the value of vaccines and leave the public in no doubt that they are safe and save lives. It’s testament to our hard-working doctors and nurses that families trust them to provide accurate facts about the effectiveness of vaccines,’ PHE chief executive Duncan Selbie said.

‘We know that inaccurate claims about safety and effectiveness can lead to doubts about vaccines – putting people at risk of serious illness. It’s vital that all websites and social media platforms ensure accurate coverage of public health issues like vaccination. We have seen some steps forward with main platforms such as Twitter and Instagram banning anti-vaxx hashtags and/or redirecting the traffic to trusted sites such as NHS.UK. But there is still work to be done.’6

One solution, being considered ‘very seriously’ by the Health Secretary Matt Hancock before the general election was announced, is to make childhood immunisations compulsory, but as Practice Nurse reported in June this year, this approach risks unintended consequences.

Writing in the BMJ, Helen Bedford and David Elliman at UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health and Great Ormond Street Hospital argue that rather than mandatory vaccination, the UK should concentrate on other methods to increase vaccine uptake, such as improving access to services.8

They suggest ensuring that general practices have an immunisation lead and adequate appointment reminders in place, and ensuring staff have adequate time to talk to parents, and have been trained to tackle any issues that arise.

‘Only when these components are in place should we consider mandatory vaccination,’ they say.

Even then, they warn of potential unintended consequences, including loss of trust in healthcare professionals. If school entry were denied, some parents may resort to home-schooling, and if vaccination were attached to welfare benefits it would be the less well off, but determined, parents who would suffer disproportionately, they add.8

In contrast, Dr Eleanor Draeger, sexual health doctor and medical writer argued that mandatory vaccination has increased uptake in other countries. ‘We would argue that the UK now needs to legislate to increase vaccination rates, as current measures aren’t keeping rates high enough to ensure herd immunity.’8

Many parents wrongly believe the rhetoric that vaccines are harmful, unnatural, and an infringement of civil liberties, she said.

Ethicists have argued that compulsory vaccination is acceptable because people who don’t vaccinate their children are potentially putting other people’s health at risk, particularly those who can’t be vaccinated and are therefore more vulnerable.

‘Passing a law that stops children attending nursery or school unless their vaccinations are up to date or they are medically exempt would allow free choice while protecting vulnerable children,’ she concludes.8

Mandatory vaccinations are nothing new: when vaccines were first introduced they were met with sceptism and fear of the loss of civil liberties, and laws were introduced in England in 1853 (later revoked) making vaccination compulsory.7 Nor are the current declines in MMR vaccination, in particular, unique. The 1970s saw a major vaccine scare in the UK following publication of a series of cases in 1974 suggesting an association between the pertussis vaccine and neurological complications. Widespread media coverage followed, and by 1977, coverage of the vaccine had declined frim 77% to 33%. No causative link was ever proved, but it took until the late 1980s for uptake to recover.7

The NHS England report, Interim findings of the Vaccinations and Immunisations Review – September 2019, states that there are a ‘multitude of factors’ that contribute to falling vaccination rates. ‘Macro-factors include changing public attitudes to expert opinion, perception of risk of diseases which are now thankfully rare, and the impact of social media.’1

That last factor, the impact of social media, may soon become even more problematic, fuelled by the US release this month of a controversial ‘documentary’ sequel – Vaxxed II: The People’s truth. It premiered in over 50 ‘secret’ locations on 6 November, with 100s more planned for the following week. The film is based on the stories of ‘doctors, scientists, nurses and parents who will no longer be silenced about the vaccine injuries they have witnessed.’9

The NHSE’s interim report focuses more on addressing the ‘micro-factors’ behind current vaccination uptake figures. These include ‘the practical logistics of accessing appointments, accurately tracking coverage, and communication with patients and parents.’1

It says it is important that the GP contract incentivises improvement in coverage – ‘in so far as general practice can influence it’. The current arrangements for remuneration for immunisations is a complex mix of item of service payments, global sum (capitation) payments and incentives. The current incentive scheme is felt to be outdated because the coverage targets (70% and 90%) are not aligned to the levels of coverage needed for population protection, and the current ‘cliff edge’ incentive design does not support improvement.1

A proposed solution is to simplify payment structures but retaining incentives for a broader range of vaccinations, including some to be aimed, in future, at primary care network level.1

The question of access is complex too. Practice engagement with the vaccination programme is high, with all but five practices offering vaccination services. General practice is considered to be delivering a high quality service, and the report says it should continue to be the main delivery route for most vaccination programmes. Accessibility and convenience of appointments are important factors in contributing to uptake levels, but general practice is noted as being a convenient and trusted provider for routine childhood immunisations, particularly for young children.1

However, expanding staffing in general practice, including practice nurses and support staff, could help to improve access. Another solution would be to supplement the services offered in general practice by expanding the immunisation service to other providers, such as community pharmacy. Another approach would be to widen the range of health professionals who provide vaccinations, to include health visitors, community nurses and expanding existing school health services.1

The NHSE advisory group, to which the RSPH contributed, also identified several broader recommendations, unrelated to contract changes, which will also be needed, including continuing to provide information about vaccine safety and effectiveness to tackle concerns about misinformation and vaccine hesitancy.1

For every vaccine explored by the RSPH, with the exception of the childhood flu vaccination, the number one reason for not getting the vaccination was fear of side effects. For some – MMR and also the HPV vaccine – fears are fanned by anti-vaccine campaigners or media scares that have led to widespread and often misleading discussion around possible side effects, despite good evidence that those fears are ill founded. The RSPH also found a lack of trust in the effectiveness of vaccines. And sadly, across the board, people are more likely to see negative messages about vaccination than positive messages. Timing and availability of appointments were the most commonly cited barriers to accessing vaccinations, but inconvenience was rarely cited as a reason for not getting vaccinated.7

The RSPH report says that a ‘multi-pronged approach to improving and maintaining uptake with be essential: reducing mistrust in the safety and efficacy of vaccines, improving awareness of the value of vaccines, and improving access to vaccines.

‘Healthcare professionals right across the health system beyond doctors and nurses, have an important role in improving uptake of vaccinations and this should be acknowledged and encouraged.’ 7

RSPH chief executive Shirley Cramer wrote: ‘With the dawn of social media, information – and misinformation – about vaccines can spread further and faster than ever before and one of the findings of [our] report is that this may, unfortunately be advantageous for anti-vaccination groups. Finding new and innovative ways to counteract “fake news” about vaccines is likely to be a major battle to be fought in the coming years.’7

REFERENCES

1. NHS England. Interim findings of the vaccinations and immunisations review – September 2019. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/interim-findings-of-the-vaccinations-and-immunisations-review-2019.pdf

2. Public Health England. Vaccine Update, August 2019; Issue 298. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/827130/PHE_Vaccine_Update_298_August_2019.pdf

3. Public Health England. Laboratory confirmed cases of measles, rubella and mumps, England: April to June 2019. Health Protection Report 2019;13(31). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/827924/hpr3119_mmr_AA.pdf

4. NHS Digital. Childhood vaccination coverage statistics – England 2018-19; 26 Sep 2019. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/nhs-immunisation-statistics/england-2018-19

5. Morris S. Totnes parents reject vaccines despite start medical warnings. The Guardian; 22 Oct 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/oct/22/this-isnt-hippy-stuff-totnes-parents-defiant-over-vaccines

6. Public Health England. Vaccine Update, May 2019; Issue 294. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/805502/PHE_vaccineupdate_294_May19.pdf

7. RSPH. Moving the needle. Promoting vaccination uptake across the life course, 2018. https://www.rsph.org.uk/uploads/assets/uploaded/f8cf580a-57b5-41f4-8e21de333af20f32.pdf

8. Draeger E, Bedford HE. BMJ 2019;365:l2359 http://www.bmj.com/content/365/bmj.l2359

9. Children’s Health Defense. Announcing ‘Vaxxed II: The People’s Truth’. 18 October 2019. https://childrenshealthdefense.org/child-health-topics/exposing-truth/announcing-vaxxed-ii-the-peoples-truth/

Related articles

View all Articles