Which way now for diabetes care?

BEVERLEY BOSTOCK

BEVERLEY BOSTOCK

RGN MSc MA QN

ANP Mann Cottage Surgery, Moreton in Marsh

PCN Nurse Coordinator, Hereford

Practice Nurse 2022;52(3):12-17

Updated guidance from NICE is at odds with international opinion - so should we follow NG28 (metformin+/-SGLT2 inhibitor) or the M21 (metformin, SGLT2 inhibitor, GLP-1 RA) route for type 2 diabetes management

Last month (February 2022), NICE published an update to its type 2 diabetes (T2D) guidance.1 This update had been highly anticipated as the guideline was initially published in 2015.

Since then, a whole raft of new therapies have been launched and all have been subject to cardiovascular outcome trials (CVOTs) aimed initially at demonstrating cardiovascular (CV) safety but then subsequently looking at whether they offered CV benefits. Both of these were important – safety, because rosiglitazone had previously been linked to increased CV risk,2 and then benefit because evidence shows that the most common cause of morbidity, mortality and cost relating to T2D relates to cardiovascular conditions.3-5 Guidance reflecting what we know about the additional benefits of glucose lowering drugs had already been published by the American Diabetes Society with the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (ADA/EASD) and this was an opportunity for NICE to update and potentially align its guidance with the consensus statement from ADA/EASD.6

In this article, we consider how well ADA/EASD and NICE align and where they diverge. We will also consider why the differences exist and how that might impact on the practitioner aiming to offer ethically and clinically sound interventions for people living with T2D. The role of lifestyle interventions in the management of T2D is recognised as an essential component but is outside the scope of the article.

By the end of this article, you will be able to:

- Determine what people with T2D need from their glucose-lowering medication

- Recognise key messages from ADA/EASD and NICE regarding the use of glucose lowering therapies

- Consider where the recommendations overlap and differ

- Reflect on how to implement the algorithms in practice

WHAT DO PEOPLE WITH T2D NEED FROM THEIR GLUCOSE-LOWERING MEDICATION?

The ideal glucose-lowering drug enables people to reach glycaemic targets without the risk of hypoglycaemic attacks, which is better for quality of life but also means that routine blood glucose monitoring will not be required. Most people with T2D are overweight or obese, so the medication should not cause weight gain and should ideally support weight loss.5,6 Cardiovascular disease, heart failure and chronic kidney disease are the most common causes of morbidity and mortality in people with T2D so any additional benefits with respect to these conditions will be desirable for the individual but also for the health economy, as the cost of managing complications accounts for around 80% of all of the money spent on T2D.5,6 In fact, research has shown that even people with non-diabetic hyperglycaemia develop CV complications before they develop T2D, so the earlier the interventions to reduce CV risk are initiated, the better.7

Although the direct costs of medication to treat diabetes make up a small slice of the pie, it would also make sense to use lower cost options if all other aspects of the medication are equal.

KEY MESSAGES FROM ADA/EASD AND NICE ON GLUCOSE LOWERING THERAPIES

In essence, the ADA/EASD consensus statement highlights three drug classes which offer the optimum risk: benefit ratio when aiming for good glycaemic control with additional benefit, as described above. These three drugs will have different levels of benefit, based on the individual in whom they are used, but they are metformin, SGLT2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) and GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA). We could refer to this triad as the M21.

M – metformin, improves glycaemic control, does not cause weight gain and may support a small weight loss, is not associated with a risk of hypoglycaemia (hypos) and studies have shown it to be cardioprotective.8

2 – SGLT2 inhibitors improve glycaemic control, promote weight loss through glycosuria, are not associated with a risk of hypoglycaemia and studies have shown that most SGLT2i drugs offer cardioprotection, and have positive outcomes for chronic kidney disease and heart failure as well as reducing blood pressure.9

1 – GLP-1 RA drugs improve glycaemic control, support weight loss, are not associated with a risk of hypoglycaemia and are cardioprotective in people with and without established cardiovascular disease.10

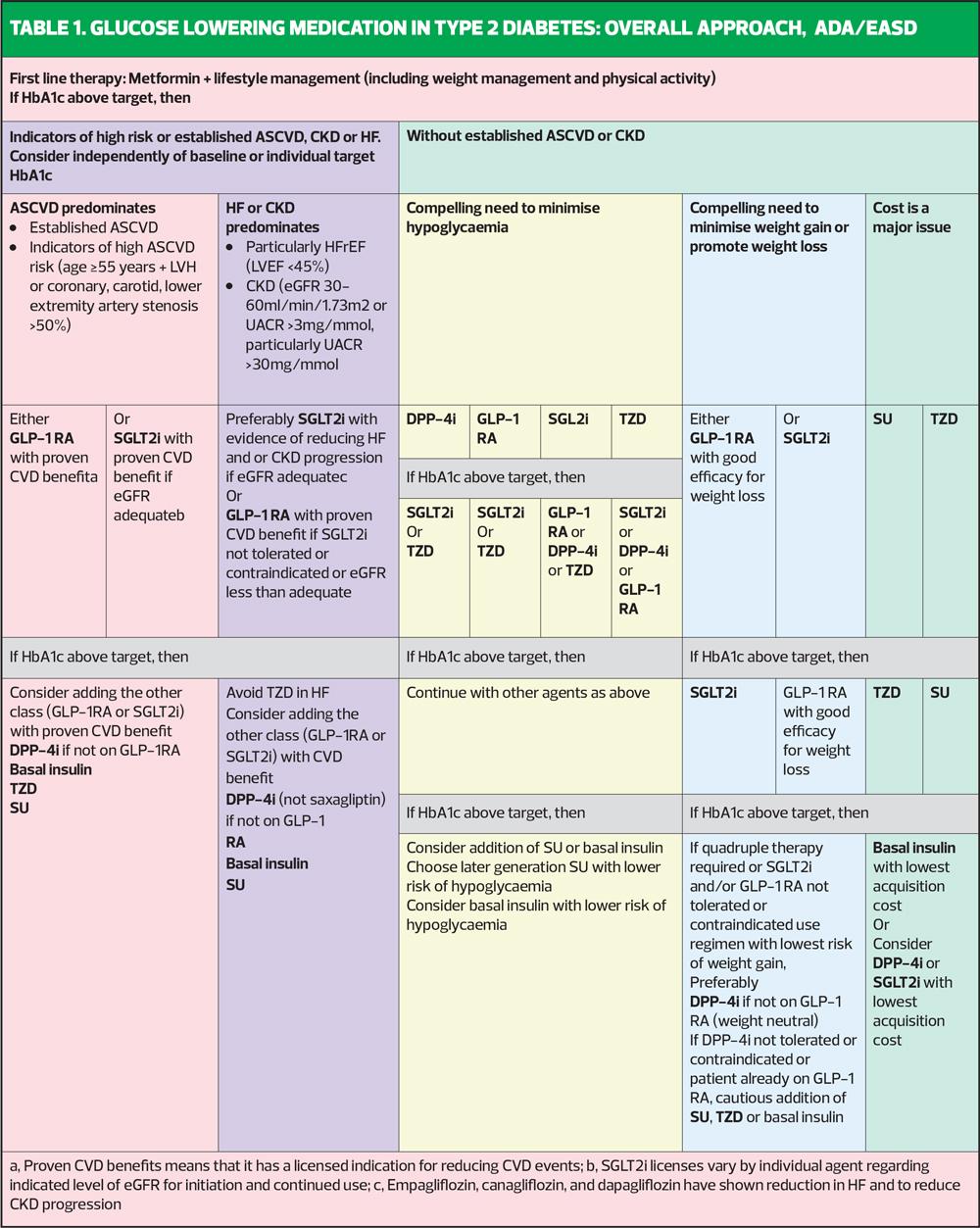

ADA/EASD

ADA/EASD says that in people with established CVD or who are at high risk of CVD, an SGLT2i or GLP-1 RA should be given after metformin (Table 1). People with heart failure or CKD should be given an SGLT2i after metformin, with a GLP-1 RA as an option if they cannot take an SGLT2i for any reason. People who want help to lose weight should be offered an SGLT2i or a GLP-1 RA; a DPP4 inhibitor will be weight neutral, whereas sulfonylureas, pioglitazone and insulin all cause weight gain. Avoidance of hypos can be achieved through using SGLT2i, GLP-1 RA and also DPP4 inhibitors (which have no CVD benefits) or pioglitazone (which is associated with heart failure risk). So in all of these categories, the two drugs which feature throughout, after metformin are the SGLT2i and GLP-1 RA therapies. ADA/EASD also stresses that the additional benefits of the SGLT2 and GLP-1 RA therapies are so important that they should be used even when the HbA1c is at target.

ADA/EASD has a separate section for cheap drugs, aimed at international health economies which may restrict access to newer therapies with evidence of additional benefits because of the comparative cost of the drugs. The drugs highlighted in this section include sulfonylureas and pioglitazone.

NICE

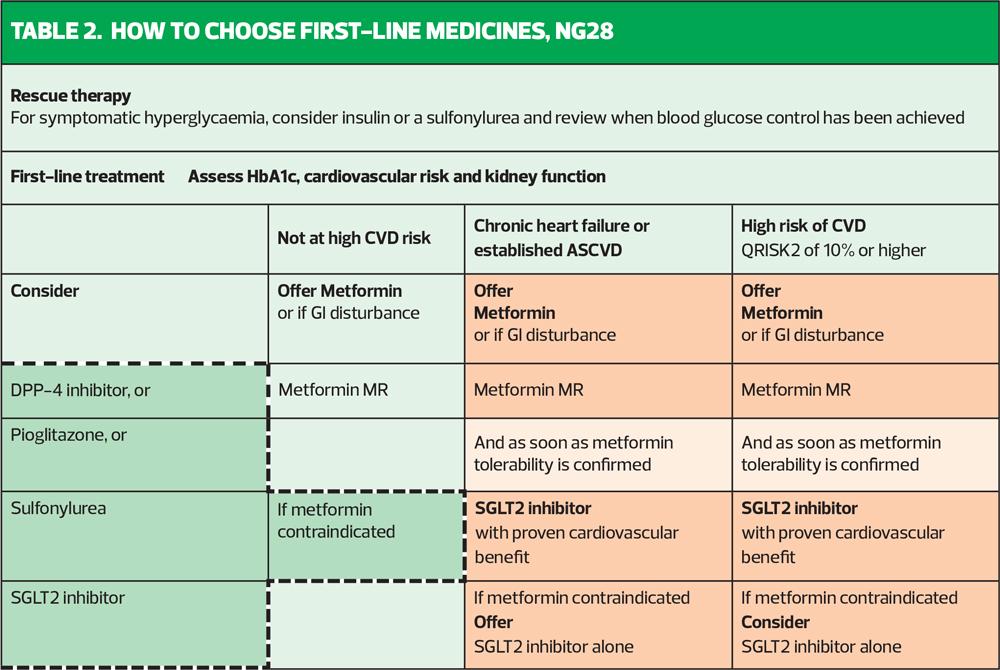

Now to the new NICE update: how does it compare? NICE agrees that metformin should remain the first line drug along with lifestyle interventions, unless contraindicated or not tolerated. It also says that any patient with a CVD risk score of 10% or more, as defined specifically by QRisk2 (not QRisk3) should also be started on an SGLT2i as soon as they are tolerating metformin (Table 2). This early addition of the SGLT2i to metformin is also recommended for people with heart failure or established CVD, which includes coronary heart disease and stable angina, current or previous acute coronary syndrome, stroke, transient ischaemic attack and peripheral arterial disease.1 Inexplicably, there is another box on the same page as this algorithm which says that SGLT2is are recommended ‘only if a DPP4i would otherwise be prescribed and a sulfonylurea (SU) or pioglitazone is not appropriate’. That statement is quite confusing. Why would a DPP4i otherwise be prescribed and when is an SU or pioglitazone ever going to be appropriate, when considering the risk: benefit ratio of all the available drugs? In the summary of first line medicines, class options are listed alphabetically and include DPP4is, metformin, pioglitazone, SGLT2is and SUs.1

NICE defines people with high risk of developing CVD as being those with a QRisk score of 10% or more or people under 40 years of age with one or more risk factors including hypertension, dyslipidaemia, smoking, obesity, or a family history of premature CVD in a parent or sibling.

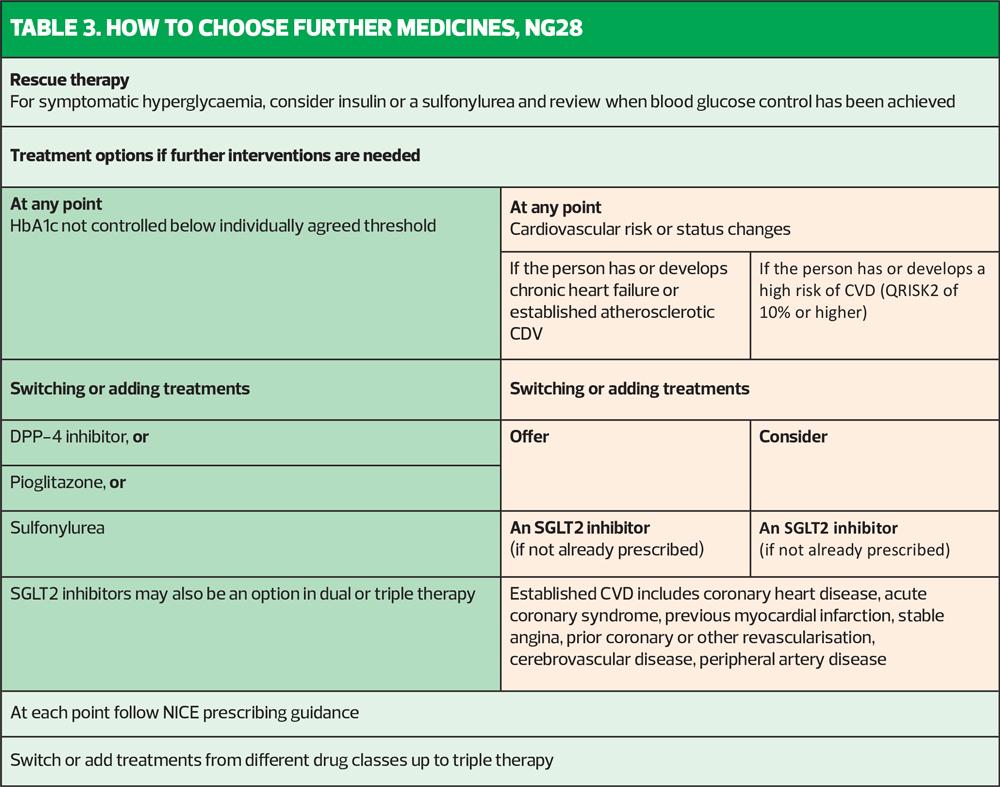

When it comes to stepping up treatment after the baseline metformin +/- an SGLT2i, there is another algorithm (Table 3). This says that if the HbA1c is not at target with the initial therapy, the clinician can switch or add in treatments. Bearing in mind that NICE appears to have clarified the role of metformin and an SGLT2i in high-risk people, it can be assumed that for those individuals, it would be a case of adding in and here is where the head scratching starts. NICE recommends as 3rd line therapy a DPP4i, or, astonishingly, an SU or pioglitazone – the drugs that we know come with a poor risk: benefit ratio.

With respect to the choice of an SGLT2i, NICE recommends that only SGLT2i with CV benefits should be used. It is important to recognise what the licence says for each SGLT2i, then, along with the evidence base for each. Canagliflozin, dapagliflozin and empagliflozin all have proven benefit and have licenses which reflect their trial data. Ertugliflozin does not have evidence of CV benefit and NICE recognises this by saying that it has no licence for reducing CV risk. That begs the question why it is still recommended. Where does that leave the practitioner, medicolegally, if the patient goes on to suffer a CV event that might have been avoided through the use of a licensed option? Could it be because ertugliflozin is cheaper than the other SGLT2is?

Cost effectiveness

Of course, this is where it becomes clear why there are differences between ADA/EASD and NICE – because NICE alone is duty bound to consider cost effectiveness as a key part of their decision-making process. The NICE standards say that cost effectiveness is the goal and that the health economist is one member of the decision-making team,11 although colleagues who have sat on NICE guideline committees often bemoan the fact that the voice of the health economists seems to be the one which gets most attention. Clinicians have implicitly criticised NICE for its focus on cost to the potential detriment of high quality, patient-focused guidance.12-14

In NG28, NICE seems to underline risks with SGLT2is such as diabetic ketoacidosis, which may make those who are less experienced in prescribing these drugs nervous about using them, and yet the risk of DKA is very small, with the benefits far outweighing the risks for the vast majority of people.1 In contrast, there is very little advice on the risks associated with SUs and where the risk: benefit ratio is likely to be far less positive.15

In CKD, NICE states that SGLT2is can be offered in addition to RAAS inhibition if patients meet the licence requirements with respect to the eGFR and have an ACR of 30mg/mmol. SGLT2i can also be considered if the ACR is above 3mg/mmol.

So summarising the NICE guidance, it seems to say that for most people the M2 (metformin + SGLT2i) approach is acceptable but a DPP4i or an SU or pioglitazone may be an option at step 2 or step 3. NICE also recommends insulin as a step 3 option – a drug which requires blood glucose monitoring, which can cause hypos and which can also cause weight gain. If insulin is needed, then it is needed, but NICE seems to say that this is a standard option for step 3 treatment. All of this leaves the conspicuous exclusion of GLP-1 RAs, which ADA/EASD has put as an option for step 2 or step 3. This is where NICE takes a clear diversion from the internationally recognised ADA/EASD consensus statement (and don’t forget that the UK had high level representation for this statement in the form of Melanie Davis, a highly esteemed diabetologist from Leicester).

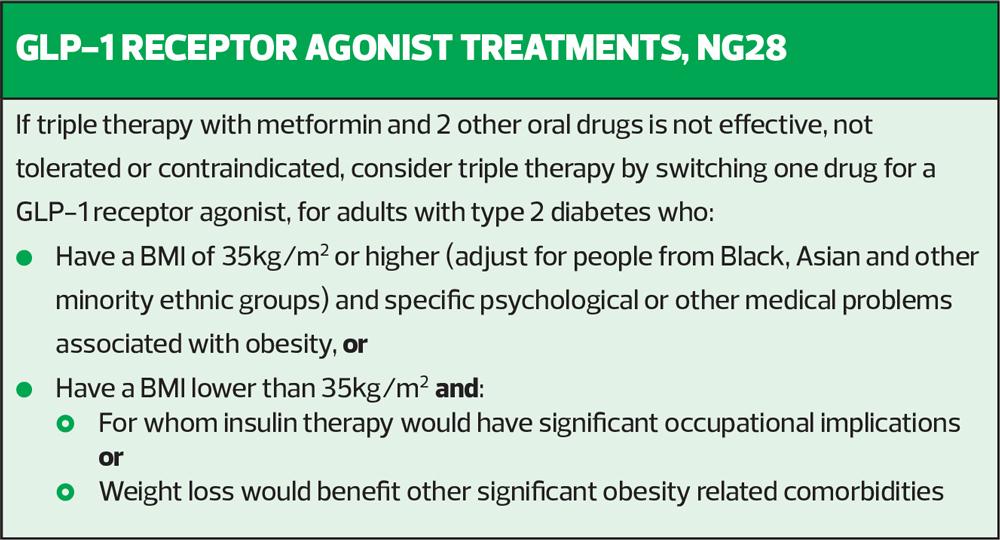

NICE has stuck to the advice it gave back in 2015, before any CVOT had been published, by pigeonholing GLP-1 RAs as drugs which reduce HbA1c and which may help people with a high BMI to lose weight (Box 1). The wording in the updated guidance is the same as in the 2015 guidance i.e. that if a patient on triple therapy has not hit their target HbA1c on triple therapy, one of the three drugs could be switched to a GLP-1 RA but only if that person has a BMI of 35kg/m2 or more (or adjusted according to ethnicity) and specific psychological or other medical problems associated with obesity (so clinicians may need to document this) or they have a BMI less than 35kg/m2 but insulin therapy would have significant occupational implications or weight loss would benefit other significant obesity related comorbidities.

How does NICE reconcile the aim stated on page one of the updated guidance, to ‘Adopt an individualised approach to diabetes care that is tailored to the needs and circumstances of adults with type 2 diabetes, taking into account their personal preferences, comorbidities and risks from polypharmacy and their likelihood of benefiting from long-term interventions’ with the lack of recognition for the place for GLP-1 RAs? The CVOTs for GLP-1 RA therapies published since 2015 led to ADA/EASD putting them as an option after metformin for people with established CVD or risk factors for CVD. Studies such as LEADER, SUSTAIN-6, and REWIND demonstrated CV benefits in a range of populations, the trials including those with and without established CVD and those with BMIs less than 30kg/m2.17-19

NICE states that the risks and benefits of treatment should be discussed, and choices based on the person’s comorbidities, weight, preferences and need, along with the effectiveness of the treatments in terms of metabolic and cardiorenal protection – which is exactly right – but then the algorithms could potentially steer people away from those principles. NICE also states that drugs that have not impacted on HbA1c or weight (stated as a reduction in HbA1c of 11mmol/mol or more and 3% weight loss within 6 months) should be stopped unless there is additional clinical benefit such as cardiovascular or renal protection and yet these benefits were clearly demonstrated in the CVOTs for liraglutide, dulaglutide and semaglutide.

When it comes to recommending which GLP-1 RA to choose, NICE again lists them all as if they are all the same and exert a class effect, something which ADA/EASD clearly disagrees with. ADA/EASD underlines the importance of using a GLP-1 RA with CVOT evidence, which can only mean liraglutide, dulaglutide or semaglutide. As a once daily option, liraglutide is less likely to be chosen by patients when the other two are once weekly injectables. Ethically, it would be inappropriate to offer a drug without benefit when there are drugs with additional benefits available – indeed it could be an important medicolegal breach of the Montgomery ruling if these points are not raised within the consultation.20

HOW TO IMPLEMENT THE ALGORITHMS IN PRACTICE

Both NICE and ADA/EASD support the idea of using drugs which have benefits beyond glycaemic control, for example avoidance of hypos, support with weight loss, and additional cardiorenal protection. ADA/EASD highlights the use of SGLT2i and GLP-1 RA with evidence of cardiorenal benefits (canagliflozin, dapagliflozin and empagliflozin; liraglutide, dulaglutide or semaglutide – see licences for details) whereas NICE still has restrictions on prescribing GLP-1 RAs. A failure to use drugs which offer holistic benefits because people are not (yet) known to be in an at-risk group, is a cause for ethical and medicolegal debate. NICE says that in people who are not known to be at high risk it is acceptable to wait until they are high risk to try to reduce their risk. It also appears to endorse the use of medications, such as sulfonylureas and pioglitazone, that may well actively increase their risk, leading to their becoming at high risk in the future. Once they are at high risk, NICE endorses the use of drugs such as SGLT2is to reduce that risk again.

Clinicians should understand that although local, national and international guidance can inform practice, ultimately decisions about treatment should be made on a shared basis between the person living with diabetes and their clinician. This means that patients are encouraged to take an active part in their care and understand the risks and benefits of the full range of interventions. This is a strong foundation for ethical, safe practice.

REFERENCES

1. NICE NG28. Type 2 diabetes in adults: management; 2015 (updated 2022) https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28

2. Nissen SE, Wolski K. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med 2007;356(24):2457–2471. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa072761

3. WHO. Diabetes (Fact sheet); 2021 https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes

4. International Diabetes Federation. 10th Diabetes Atlas; 2021 https://diabetesatlas.org/atlas/tenth-edition/

5. Public Health England. Health matters: preventing Type 2 Diabetes; 2018 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-preventing-type-2-diabetes/health-matters-preventing-type-2-diabetes

6. Buse JB, Wexler DJ, Tsapas A, et al. 2019 Update to: Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, 2018. A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes care 2020;43(2):487–493. https://doi.org/10.2337/dci19-0066

7. Brannick B, Dagogo-Jack S. Prediabetes and Cardiovascular Disease: Pathophysiology and Interventions for Prevention and Risk Reduction. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am 2018;47(1):33–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecl.2017.10.001

8. Driver C, Bamitale K, Kazi A, et al. (2018). Cardioprotective Effects of Metformin. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2018;72(2):121–127. https://doi.org/10.1097/FJC.0000000000000599

9. Vallon V, Verma S. Effects of SGLT2 Inhibitors on Kidney and Cardiovascular Function. Ann Rev Physiol 2021;83:503–528. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-physiol-031620-095920

10. Sattar N, Lee M, Kristensen SL, et al. Cardiovascular, mortality, and kidney outcomes with GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised trials. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2021;9(10):653–662. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00203-5

11. NICE PMG6. The guidelines manual: Process and Methods. 7. Assessing cost effectiveness https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg6/chapter/assessing-cost-effectiveness#the-role-of-the-health-economist-in-clinical-guideline-development

12. British Thoracic Society. BTS response to new NICE asthma guidelines; 2018 https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/news/2017/bts-response-to-new-nice-asthma-guidelines/

13. Price C. NICE risks making itself a 'laughing stock' over guidance on metformin alternatives, say experts. Pulse Today. February 2015. www.pulsetoday.co.uk/clinical/more-clinical-areas/diabetes/nice-risks-making-itself-a-laughing-stock-over-guidance-on-metformin-alternatives-say-experts/20009139

14. O'Hare J, Hanif W, Millar-Jones D, et al. NICE guidelines for type 2 diabetes – revised but still not fit for purpose. Diabet Med 2015; 32 (11): 1398–1403. Available at: doi: 10.1111/dme.12952

15. Raparelli V, Elharram M, Moura CS, et al. Sex Differences in Cardiovascular Effectiveness of Newer Glucose-Lowering Drugs Added to Metformin in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. J Am Heart Assoc 2020;9(1): e012940. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.119.012940

16. Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics Oxford : Oxford University Press; 2013

17. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes N Engl J Med 2016; 375:311-322 DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1603827

18. Marso SP, Bain SC, Consoli A, et al.; SUSTAIN-6 Investigators Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2016;375:1834–1844pmid:27633186

19. Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, et al (2019) Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes (REWIND): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2019;394(10193):121-130 https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(19)31149-3/fulltext

20. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The impact of the Montgomery ruling; 2016 https://www.rcog.org.uk/globalassets/documents/members/membership-news/og-magazine/december-2016/montgomery.pdf