Time for practice nurses to lead the way with type 2 diabetes remission?

Dr Ellen Fallows

Dr Ellen Fallows

BMBCh BA Oxon, MRCGP, DipIBLM

GP, Clinical Advisor MomentaNewcastle

(NHS Low Calorie Diet Diabetes Programme), Learning Academy Lead,

The British Society of Lifestyle Medicine

Practice Nurse 2021;51(4):24-29

General practice nurses are uniquely placed to talk about a brighter future for people with type 2 diabetes, and starting this conversation is likely to be so much more rewarding than focusing only on our current monitor and medicate approach

People with type 2 diabetes receive almost all their care in general practice where an average 20 million diabetes contacts occur annually.1 Practice nurses deliver much of this care through an annual or bi-annual diabetes review appointment and follow-up. Practice nurses also manage people with diabetes during leg ulcer dressing appointments and other chronic disease reviews. During these appointments there is an opportunity to share with patients the message of hope regarding potential remission of Type 2 diabetes.

Remission usually occurs following significant weight loss. Weight loss can be achieved by helping patients to change what they eat, how much and how often they eat, how active they are, how much sleep they get and how they manage stress. Practice nurses are ideally placed to support people with these lifestyle changes as they often have trusted and long-term relationships with patients. These relationships help particularly when combined with proven techniques to support people to achieve sustainable lifestyle changes and encourage engagement in programmes that offer more intensive support. Many of the research interventions achieving successful remission have been delivered in primary care by general practice nurses.

Primary care nurses are uniquely placed to talk about a brighter future for people with type 2 diabetes. Starting off this conversation, using proven techniques to support lifestyle and behaviour change and sign-posting to resources for self-care is likely to be so much more rewarding than remaining focused only our current monitor and medicate approach. This article aims to give you the background and tools to start conversations about remission with patients.

WHAT IS TYPE 2 DIABETES REMISSION?

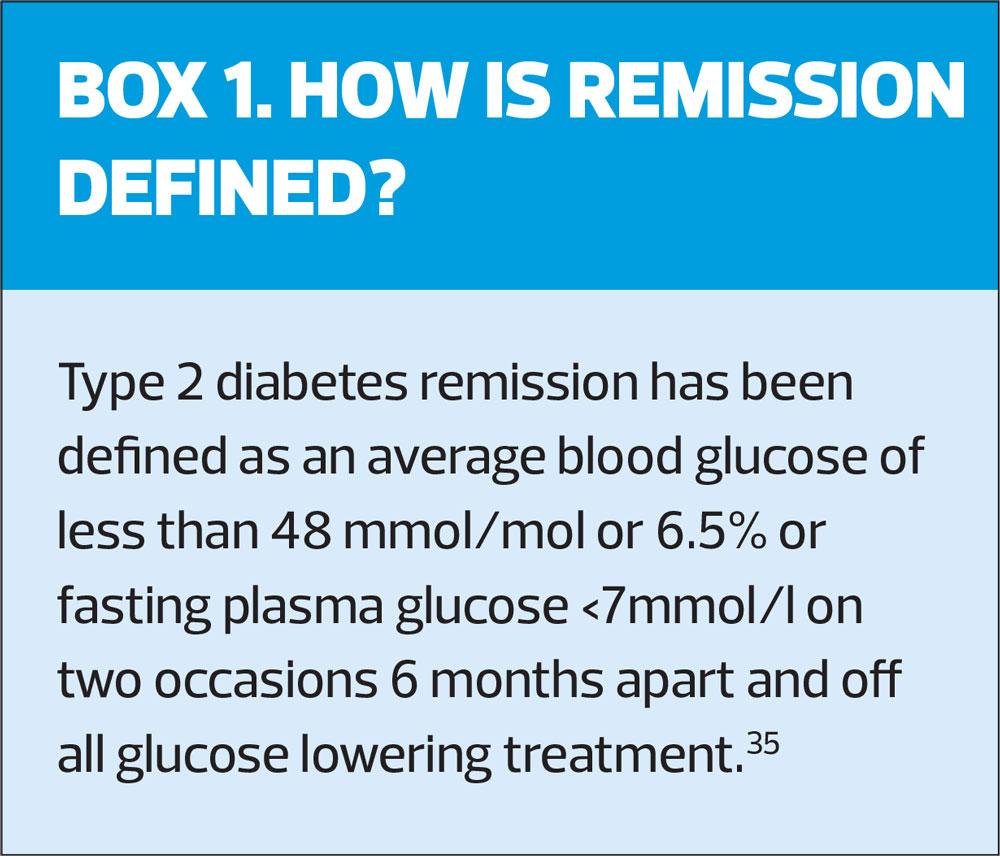

Over 4 million people in the UK are thought to have type 2 diabetes,2 and until recently, most clinicians would discuss the condition in terms of it being a progressive and incurable condition. Although lifestyle approaches have always been recommended as first line in the management of diabetes, there was little to suggest that people could normalise their blood glucose without medications or bariatric surgery (an approach only available to only a few people on the NHS who are prepared to accept the life-long effects of such surgery). Evidence suggests that clinicians lack the skills and confidence to support people with behaviour and lifestyle change and most of us aren’t talking to our patients about the impact of lifestyle factors.3 However, recent trials have shown that people can normalise glucose levels – without medications – to be considered as having put Type 2 diabetes in remission (for the agreed definition see box 1).

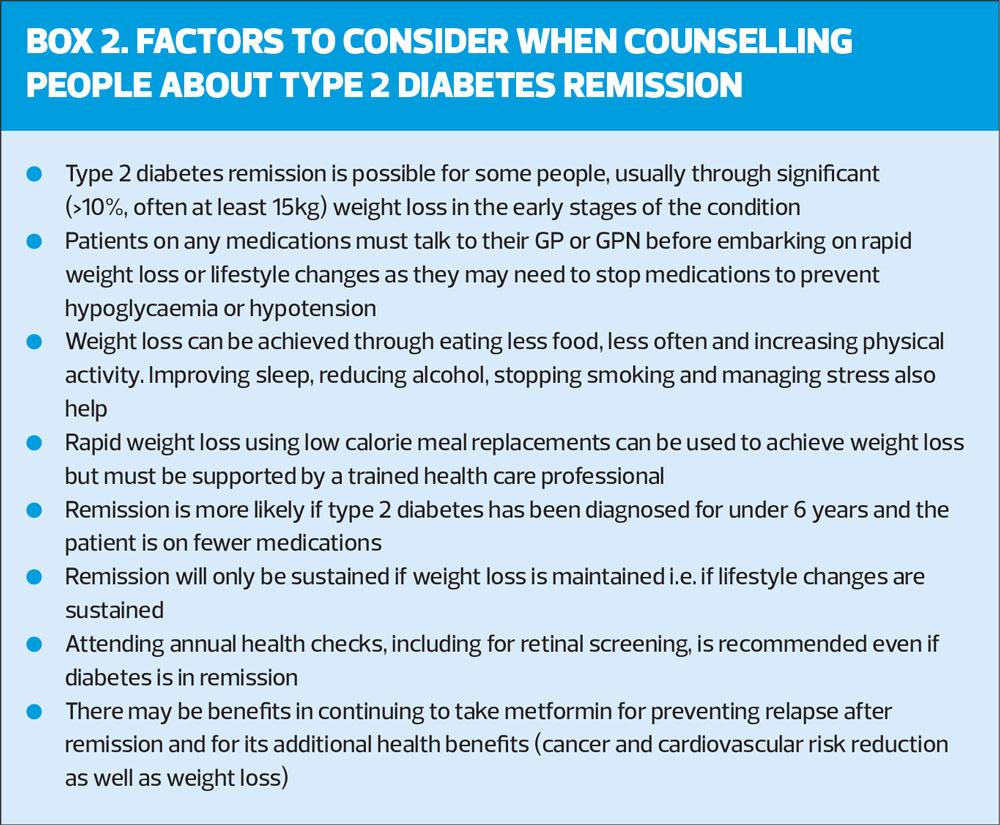

The term remission is preferred to ‘cure’ or ‘reversal’, as it is likely that type 2 diabetes will return if weight is regained or if lifestyle changes are not sustained. When we talk to people about remission, it is important to counsel about the possibility of relapse and the need to continue with lifestyle changes along with annual check-ups, in particular retinal screening as retinopathy can progress despite remission (see Box 2: Factors to consider when counselling patients about remission).

EVIDENCE THAT REMISSION IS ACHIEVABLE IN PRIMARY CARE

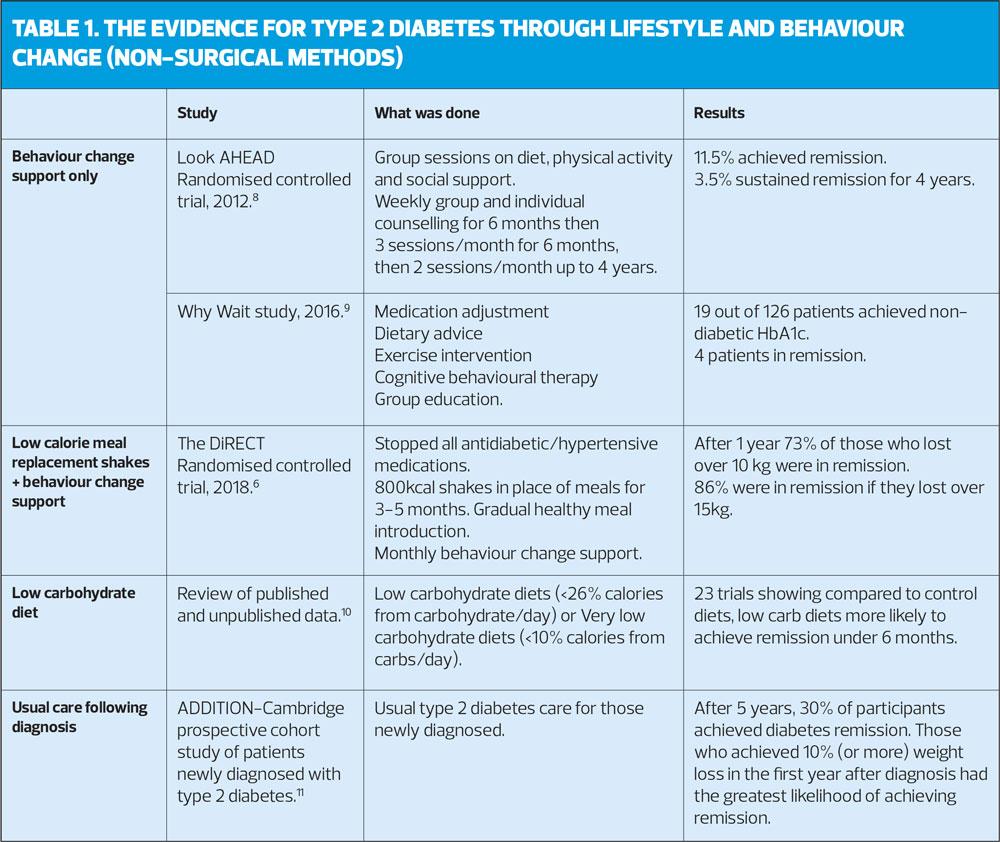

Management of type 2 diabetes traditionally involved simple lifestyle advice to lose weight and move more, followed by a step-wise increase in medications to reduce blood glucose ultimately often resulting in insulin treatment around 8-10 years after diagnosis.4 This approach has been challenged by studies that use a variety of more intensive and comprehensive behaviour interventions to support weight loss and lifestyle change not just to prevent type 2 diabetes but to treat and put it into remission (see Table 1). Similar interventions have already been shown to successfully prevent type 2 diabetes and have been rolled out widely as the NHS Diabetes Prevention Programme.5

The most impressive results of a behaviour and lifestyle intervention to treat diabetes were seen in the DiRECT trial in 2018.6 This trial supported people with established type 2 diabetes to stop all of their diabetes and blood pressure medications and use 800 kcal shakes in place of meals for 3-5 months, followed by a gradual healthy meal introduction with monthly support. The support included a 1:1 structured programme to promote healthy behaviour change, including nutrition and physical activity. The programme was delivered in primary care by practice nurses or dieticians. Nearly half of the participants (46%) achieved remission after 1 year and 36% by the second year. Remission was most often seen in those who managed to lose over 10kg, for example after 1 year, 73% of those who lost over 10 kg were in remission, and 86% were in remission if they lost over 15kg.7

Other studies have shown that diabetes remission is possible through behaviour support alone, usually by offering intensive support to address nutrition and physical activity.8,9 However, the success rates are lower than that seen with meal replacement alongside behaviour change support. Similarly, a low or very low carbohydrate diet can help achieve diabetes remission at least in the short term (under 6 months).10 However, there are many unknowns around low-carbohydrate approaches and their long-term health consequences, particularly if a high fat or high meat diet is followed, which may impact on cancer or cardiovascular risk.

Simply delivering usual care following diagnosis is already motivating many patients to lose significant weight and achieve remission – 30% of those followed in the ADDITION-Cambridge study achieved remission in the first 5 years after diagnosis, suggesting that this is a time when people are most likely to be motivated. More frequent remission could be seen if intensive support was given at the key time of diagnosis.11

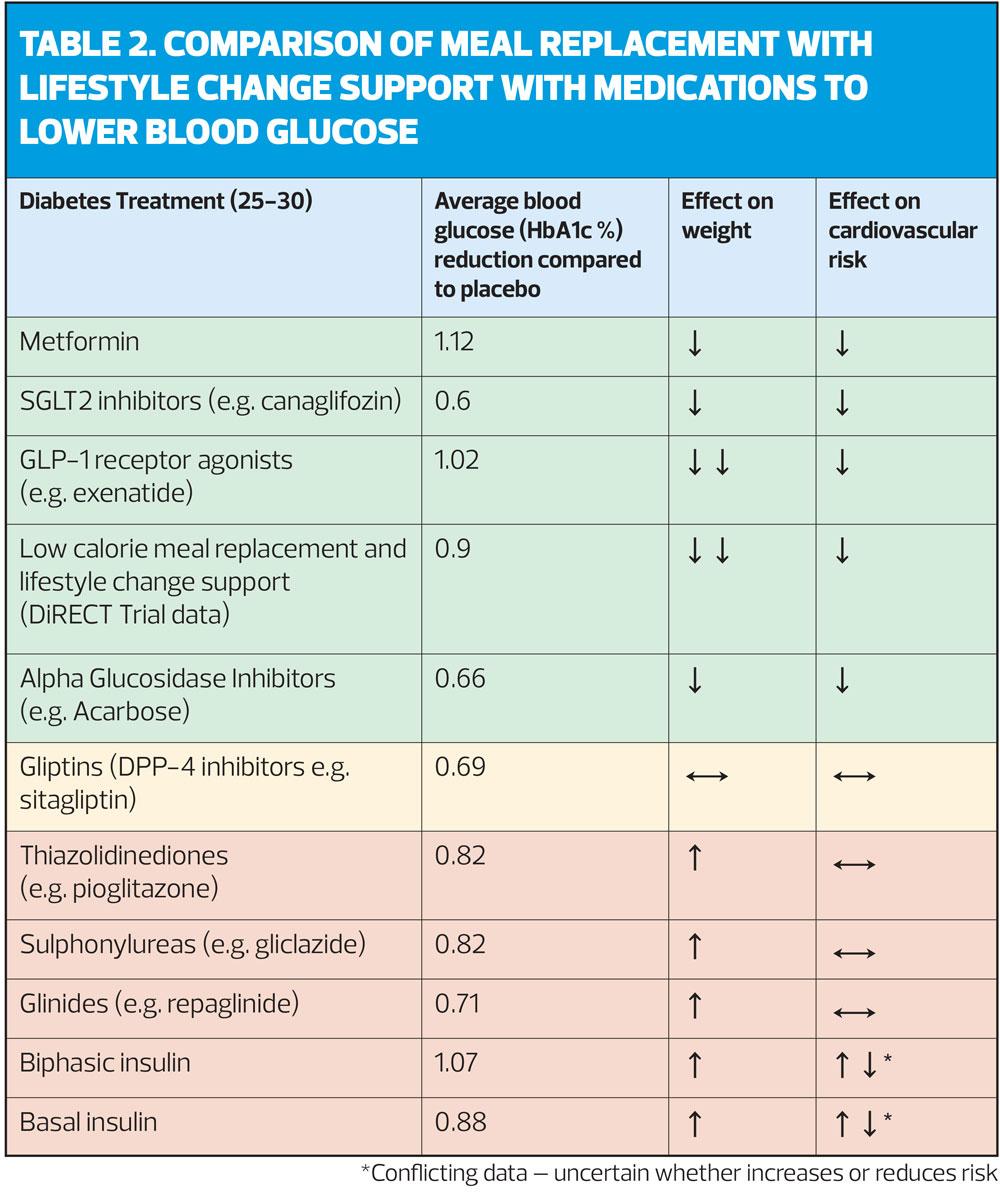

It is useful to compare the impact of lifestyle interventions with the effects of the medications we currently use to lower blood -- levels. This intensive support can achieve a greater blood glucose reduction and weight loss than most of our currently used medications (see Table 2). Some of these medications may even increase cardiovascular risk and weight. These are critical issues for people with type 2 diabetes whose lives are most often shortened by heart attacks and strokes and whose health is impacted by weight. Many of these medications also involve a significant treatment burden, for example, insulin requiring injections, the risk of hypoglycaemia and the need for frequent monitoring using a finger-prick test. It is therefore essential that patients should be informed at every opportunity of all their treatment options, including intensive lifestyle change, as well as medications.

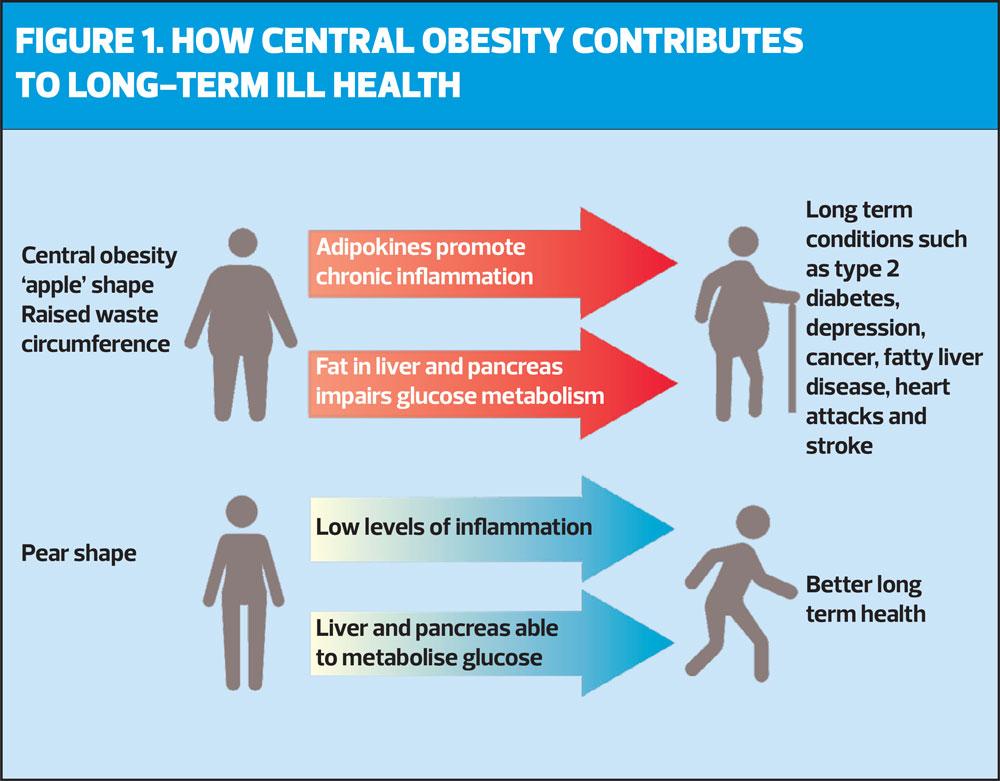

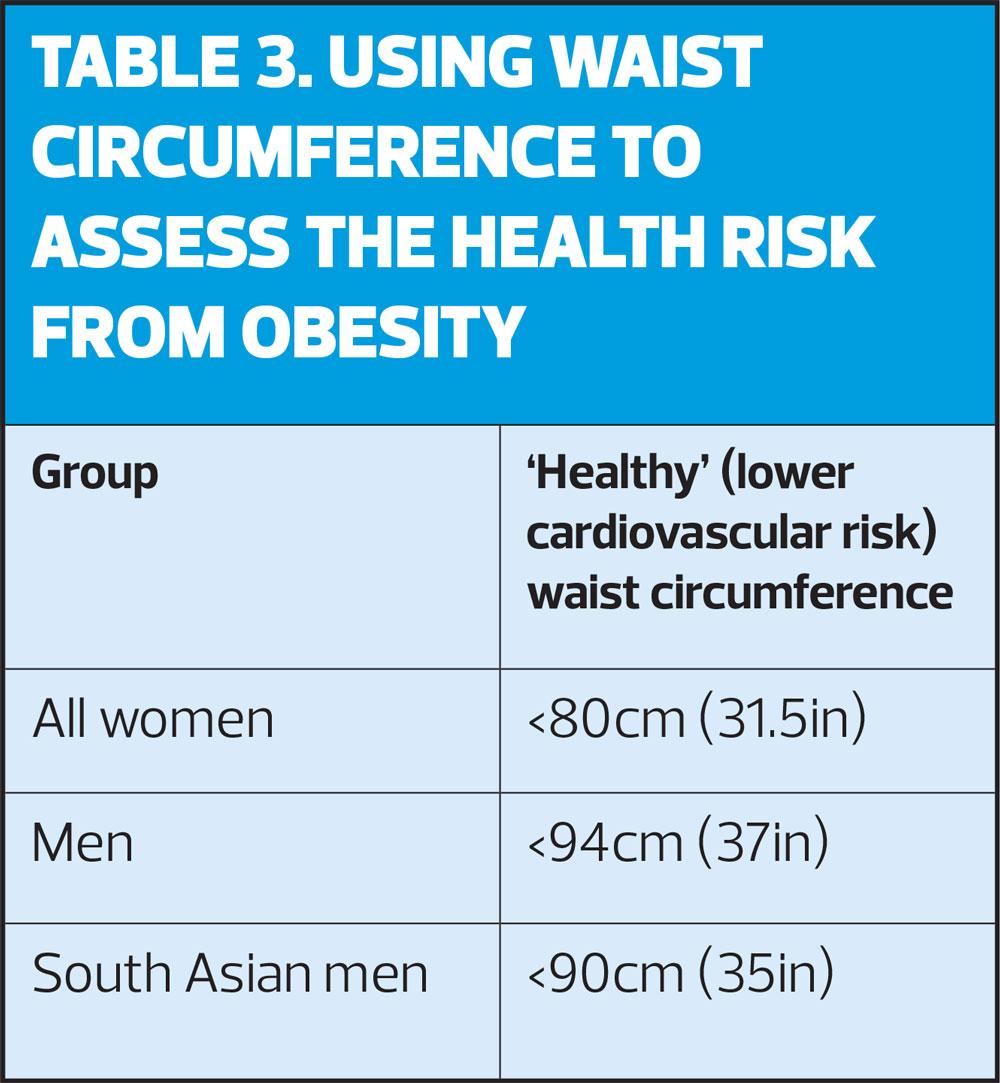

As a result of the DiRECT trial, lead researcher Professor Roy Taylor published a book for patients that describes Type 2 diabetes as ‘chronic food poisoning’12 and, following the trial’s publication, there are calls for a shift in our approach away from simpy managing the condition to treating one of its root causes: food.13 Excess weight, specifically central obesity, drives type 2 diabetes. Central obesity is particularly risky for health as fat stored around the middle of our bodies and in our abdominal organs (particularly in the liver and pancreas) is not inert but produces harmful substances. These substances (known as adipokines) act on the cells of the immune system to cause chronic inflammation which raises the risk of diabetes, heart attacks and strokes, as well as many other long-term conditions including depression and cancer.14 Fat stored in an ‘apple’ rather than a ‘pear’ body shape is therefore a key driver of ill health (Figure 1). Waist circumference can be a useful indicator for central obesity and health risk, and can be used in our patient reviews in addition to BMI (Box 3).

Supporting people to lose weight through lifestyle change is complicated and needs more than just primary care nursing. Public, politicians and clinicians will all need to work together to address multiple complex political, social, cultural and healthcare challenges as set out in the Foresight Obesity report.15 However, the DiRECT and LOOKAHEAD trials demonstrated significant and sustained weight loss by patients supported in primary care by practice nurses after only 8 hours of training. Practice nurses are already providing excellent care for type 2 diabetes, for example the rate of nurse consultations was strongly associated with higher diabetes Quality Outcome Framework (QOF) performance,16 with a lower rate of referral to secondary care.17

It can be challenging to discuss remission through lifestyle change in short consultations with competing agendas such as data collection for QOF, reviewing medications and opportunistic vaccinations. There is also no in-house primary care total diet replacement programme yet, although the NHS low calorie diet replacement programme is currently piloting a service supported by a primary care referral.18

HOW GPNs CAN SUPPORT PATIENTS TO ACHIEVE REMISSION

Despite the challenges faced by practice nurses in busy consultations, there is so much potential in just starting a conversation about remission. Critical to these conversations is to engage patients. Some patients will already be motivated to make lifestyle changes and need only simple advice and sign-posting to information with safety-netting, others will need significant time and support and may only be able to prioritise this approach at another time in their lives. However, starting the conversation, offering hope about remission and keeping the door open for future conversations is likely to have a significant impact on the diabetes epidemic.

One of the best ways to start discussing diabetes remission in consultations is to listen to what really matters to patients by asking ‘what matters to you about your health right now?’. This approach is known as Person Centred Care or Personalised Care and is a major focus for the NHS following the Long-Term Plan in England and now through the work of The Personalised Care Institute.19 Personalised care advocates for the use of shared decision making, care and support planning, supported self-care, social prescribing and personal health budgets to achieve better health outcomes for people. Using these tools is particularly helpful when we need to engage people to change behaviours. Much less effective is a paternalistic (giving instructions) or ‘lecturing’ approach or even the use of scare tactics and ‘blame and shame’. These sorts of conversations are less likely to engage people to make lifestyle changes. This is supported by a study showing – unsurprisingly – that type 2 diabetes remission is more likely to be achieved by those who receive more empathic and better-quality care.20

Once the patient has felt understood and we are aware of their own health priorities, it may be the right time to approach the topic of diabetes remission. Patients are often keen to know about options that don’t involve medications and may be unaware that remission could be achievable. This message of hope can help when introducing the more sensitive topic of weight. The prevalence of weight discrimination is over 60% in the UK (higher than racial or sexual discrimination) and health care professionals have been ranked second only after family members for obesity bias and discrimination.21 It is likely, therefore, that people may have had several past unproductive or even upsetting discussions around weight with health care professionals.

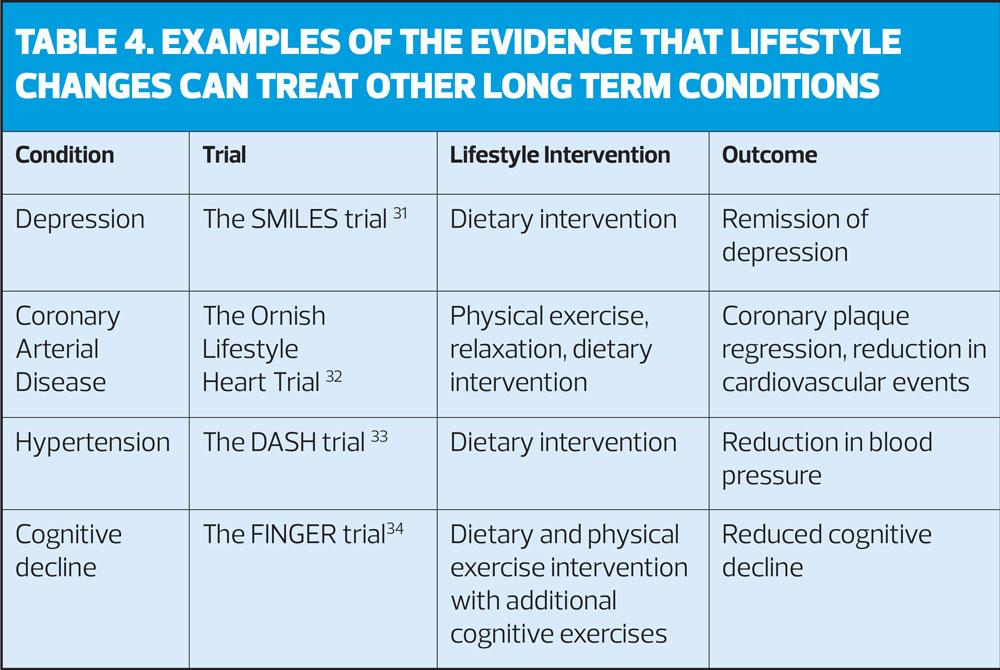

After understanding more about our patient’s health agenda and having raised the topic of remission and weight, we could discuss how changes in lifestyle including physical activity, sleep, stress management and healthier eating can improve and potentially put type 2 diabetes into remission. Most patients with type 2 diabetes have multiple other long-term conditions, and evidence shows that lifestyle changes are not just for prevention but can treat and reverse other conditions too (see Table 4). Discussing how lifestyle changes could impact other areas of people’s lives may provide additional motivation.

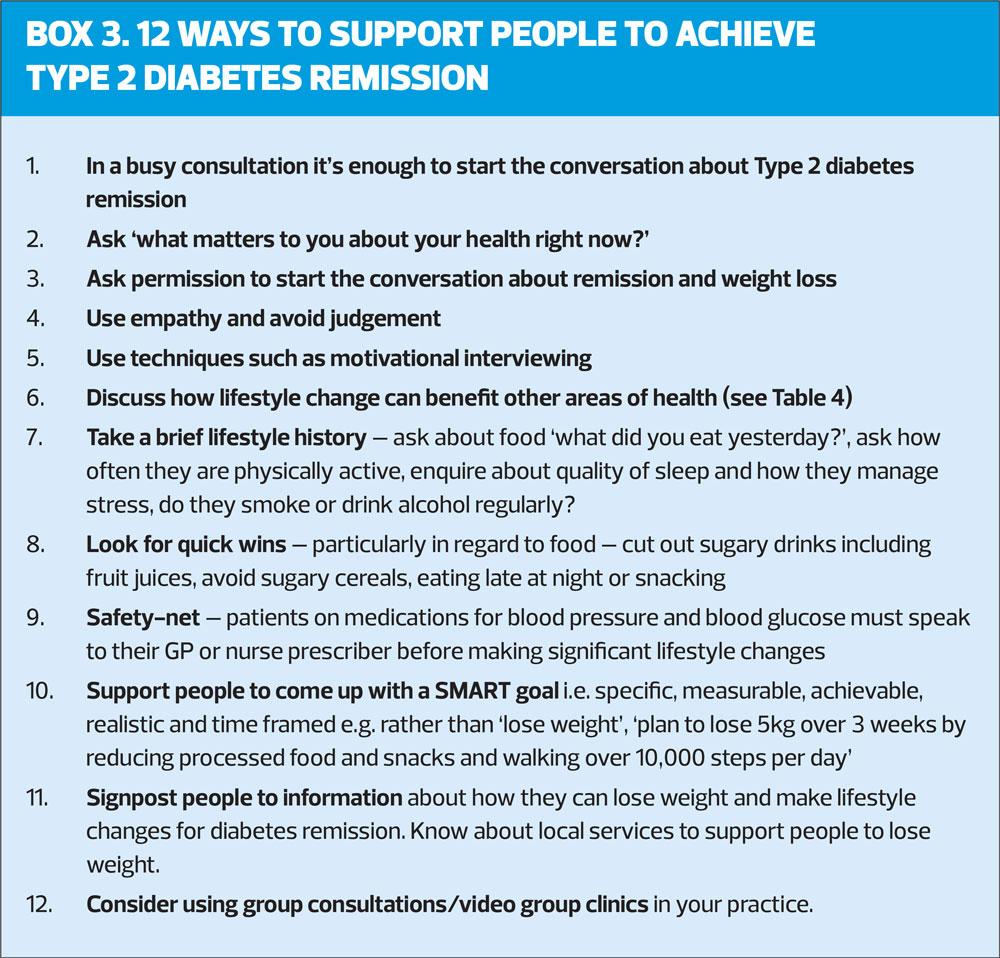

Once a patient is engaged and activated to make changes, motivational interviewing (MI) techniques and setting of SMART goals can help to make progress (Box 3). MI describes a way of consulting with patients that focuses on using empathy, reflective listening, rolling with rather than challenging any resistance to change and avoiding the ‘righting reflex’ or simple advice giving. It is an approach that supports people’s self-efficacy by summarising and reflecting back what you have heard patients suggest they could change and where you positively affirm any suggestions patients come up with regarding change. These techniques would benefit from more time than the average nurse appointment so group consultations with patients in facilitated groups can be a useful way to support people wanting to achieve remission, and have been found to improve outcomes particularly for type 2 diabetes care.22 Group consultations allow people more time with their clinicians as well as providing many potential benefits such as reducing social isolation, supporting self-care through peer support and problem solving (Box 3). Group consultations are now being used on video platforms in the UK and internationally.23 A tool kit of resources and information about how to set up video group clinics can be found on the e-Learning for Health website which is free for anyone with an NHSmail address.24

CONCLUSION

In summary, type 2 diabetes can be put into remission without medications by supporting people with significant weight loss through lifestyle changes. The NHS currently spends 10% of its budget on type 2 diabetes and £1 billion a year on diabetes medications alone.2 It is not difficult to imagine the impact if these funds were used to support practice nurses to work with patients to achieve remission. Despite the challenges in primary care, all of us, from GPs, nurse leaders and nurse practitioners can promote this approach and start these conversations off with patients. From experience, most of whom will reply, ‘why has no one told me about this before?’

REFERENCES

1. Hobbs FDR, Bankhead C, Mukhtar T, et al. National Institute for Health Research School for Primary Care Research. Clinical workload in UK primary care: a retrospective analysis of 100 million consultations in England, 2007-14. Lancet 2016;387(10035):2323-2330

2. Wicher CA, O’Neill S, Holt RIG. Diabetes in the UK:2019, Diabetic Med 2020;37:242-247

3. Duaso MJ, Cheung P. Health promotion and lifestyle advice in a general practice: what do patients think? J Adv Nurs 2002;39(5):472-9.

4. Nathan DM. Initial management of glycemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2002; 347: 1342– 1349

5. NHS England. NHS Diabetes Prevention Programme. https://www.england.nhs.uk/diabetes/diabetes-prevention/

6. Lean ME, Leslie WS, Barnes AC, et al. Primary care-led weight management for remission of type 2 diabetes (DiRECT): an open-label, cluster-randomised trial. Lancet 2018:391(10120):541-551.

7. Thom G, Messow CM, Leslie WS, et al. Predictors of type 2 diabetes remission in the Diabetes Remission Clinical Trial (DiRECT). Diabetic Med 2020;00:e14395.

8. Gregg EW, Chen H, Wagenknecht LE, et al. Association of an intensive lifestyle intervention with remission of type 2 diabetes. JAMA 2012;308(23):2489–2496

9. Mottalib A, Sakr M, Shehabeldin M, et al. Diabetes remission after nonsurgical intensive lifestyle intervention in obese patients with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Res 2015;2015:468704.

10. Goldenberg J Z, Day A, Brinkworth G D, et al. Efficacy and safety of low and very low carbohydrate diets for type 2 diabetes remission: systematic review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished randomized trial data BMJ 2021; 372 :m4743

11. Dambha-Miller H, Day AJ, Strelitz J, et al. Behaviour change, weight loss and remission of type 2 diabetes: a community-based prospective cohort study. Diabetic Med 2019;37(4):681-688

12. Life Without Diabetes: the definitive guide to understanding and reversing your Type 2 diabetes, Professor Roy Taylor, Short books Ltd, 2019

13. Morris E, Jebb S, Aveyard P. Type 2 diabetes: treating not managing. Lancet Diabet Endocrinol 2019;7:10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30071-3

14. Brestoff JR, Artis D. Immune regulation of metabolic homeostasis in health and disease. Cell. 2015;161(1):146-160.

15. Butland B, et al. Foresight Tackling Obesities: Future Choices – Project Report, Government Office for Science, 2007. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/

reducing-obesity-future-choices

16. Dambha-Miller H, Griffin SJ, Kinmonth AL, et al. Provision of services in primary care for type 2 diabetes: a qualitative study with patients, GPs, and nurses in the East of England, Br J Gen Pract 2020;70 (698): e668-e675.

17. van Dijk CE, Verheij RA, Hansen J, et al. Primary care nurses: effects on secondary care referrals for diabetes. BMC Health Serv Res, 2010;10:230

18. Feinmann J. Type 2 diabetes: 5000 patients to test feasibility of “remission service”. BMJ 2018; 363:k5114

19. Personalised Care Institute. https://www.personalisedcareinstitute.org.uk/

20. Dambha-Miller H, Day A, Kinmonth AL, Griffin SJ. Primary care experience and remission of type 2 diabetes: a population-based prospective cohort study. Family Practice 2021;38(2):141-146

21. Puhl RM, Brownell KD. Confronting and coping with weight stigma: an investigation of overweight and obese adults. Obesity 2006;14(10):1802-15

22. Booth A, et al. What is the evidence for the effectiveness, appropriateness, and feasibility of group clinics for patients with chronic conditions? A systematic review. Health Serv Deliv Res 2015;3(46)

22. Feinmann J. Low calorie and low carb diets for weight loss in primary care BMJ 2018;360:k1122

23. Birrell F, Lawson R, Sumego M, et al. Virtual group consultations offer continuity of care globally during Covid"19. Lifestyle Med 2020;1:e17

24. e-Learning for Healthcare. https://www.e-lfh.org.uk

25. Hirst J et al. Quantifying the effect of metformin treatment and dose on glycaemic control. Diabetes Care 2012;35:446-454

26. Monami M, Nardini C, Mannucci E. Efficacy and safety of sodium glucose co"transport"2 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes: a meta"analysis of randomized clinical trials. Diabet Obes Metab 2014;16:457-466

27. Liu S"C, Tu Y-K, Chien M"N, Chien K"L. (2012), Effect of antidiabetic agents added to metformin on glycaemic control, hypoglycaemia and weight change in patients with type 2 diabetes: a network meta"analysis. Diabet Obes Metab 2012;14:810-820. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1326.2012.01606.x

28. Das SR, Everett BM, Birtcher KK, et al. 2020 Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on Novel Therapies for Cardiovascular Risk Reduction in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Solution Set Oversight Committee. J Am Coll Cardiolol 2020;76(9):1117-1145

29. Ferrannini E, DeFronzo RA. Impact of glucose-lowering drugs on cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Eur Heart J 2015;36, 34:2288-2296,

30. Bonadonna RC, Borghi C, Consoli A, Volpe M. Novel antidiabetic drugs and cardiovascular risk: Primum non nocere. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2016;26(9):759-766

31. Jacka FN, O’Neill A, Opie R, et al. A randomised controlled trial of dietary improvement for adults with major depression (the SMILES trial). BMC Medicine 2017;15:23

32. Ornish D, Scherwitz LW, Billings JH, et al. Intensive lifestyle changes for reversal of coronary heart disease. JAMA 1998;280, 2001-2007.

33. Appel LJ, Moore TJ, Obarzanek E, et al. A clinical trial of the effects of dietary patterns on blood pressure. DASH Collaborative Research Group. N Engl J Med 1997;336(16):1117-24

34. Ngandu T, Lehtisalo J, Solomon A, et al. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;85(9984):2255-2263

35. Nagi D, Taylor R. Remission of Type 2 Diabetes: A position Statement from the Association of British Clinical Diabetologists (ABCD) and the Primary Care Diabetes Society (PCDS). Br J Diabet 2019;19(1):10.15277 https://bjd-abcd.com/index.php/bjd/article/view/453/0