Taking diabetes care to housebound patients at home

Emily Bond

Emily Bond

MPharm, PGCert, MRPharmS, MPCPA

Clinical Pharmacist Prescriber

Strawberry Health PCN, Hampshire

Practice Nurse 2021;51(7):14-17

Adopting a multidisciplinary, multimorbidity approach has enabled one primary care network to increase support for housebound patients with diabetes through the COVID-19 pandemic.

Diabetes increases the risk of COVID-19-related mortality, by up to three-and-a-half times in people with type 1 diabetes. Among people with type 2 diabetes, the risk of dying from COVID-19 is twice that of those without the condition.1,2 There is also evidence that glycaemic control affects outcomes: mortality risk for patients with type 1 diabetes who acquire COVID-19 is twice as high if their HbA1c is above 86mmol/mol compared with an HbA1c level of 48-53mmol/mol. For patients with type 2 diabetes the risk is 1.6 times greater in patients who are well controlled compared to those with poor control, using the above thresholds.1 Those who live with diabetes who are also housebound generally have additional challenges, such as severe frailty, disabilities and/or complex multi-morbidities, while conversely having less access to clinical care.3 There is therefore a clear concern that this vulnerable practice population requires a specialised solution.

In early October 2020, it was predicted that the oncoming second wave would incur rapid viral spread,4 combined with the usual fear of the impact of winter on hospitalisations and significant mortality among high risk individuals. Against this background, I turned my attention to our practice cohort of housebound patients with diabetes. I felt there was value and an ethical need to ensure this population could be reviewed comprehensively, not only in terms of diabetes but also any other comorbidities. I approached the pharmaceutical company NAPP for a Medical and Educational Goods and Services (MEGS) grant* as I felt this would be a good way to ensure the funds were ringfenced for this specific purpose in case other priorities came along in this unpredictable health climate.

*Since the commencement of this initiative, the Association for the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) has revised its code of practice, and replaced the MEGS grant process with a new ‘Donations and Grants’ scheme. See Clause 23, https://www.abpi.org.uk/media/8609/240621-abpi-code-of-practice_final.pdf

HOMEWELL: OUR PEOPLE, OUR PRACTICE

The Homewell Practice is located in Havant, Hampshire, England. We have a practice population of approximately 13,500 patients. According to the Havant Borough Profile 2018, life expectancy is 10.5 and 7.8 years lower for men and women, respectively, in the most deprived areas of the Borough compared with the least deprived areas. Havant experiences almost double the rate of economic inactivity (as a result of long-term sickness and disability) compared with the average rate in Hampshire. The Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) show that Leigh Park (a large suburb of Havant) has some of the most deprived wards in England.5 A Diabetes UK6 report in 2012 showed that deprivation is strongly associated with higher levels of obesity, physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, smoking and poor blood pressure control, all of which are linked to the risk of developing type 2 diabetes, and significantly increases the risk of complications among those already diagnosed with either type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

AIMS OF THE PROJECT

Our proposal was to provide a comprehensive health optimisation and monitoring service to all patients at the Homewell Practice identified as living with diabetes and housebound. We were also aware that these patients were likely to have a high rate of multimorbidity and proposed to provide a structured medication review (SMR) and multimorbidity review. NAPP agreed to support us with this agenda, funding both the home visits and the hours needed for clinical follow up.

An EMIS search was carried out to identify patients who were currently coded as ‘housebound’ or ‘temporarily housebound’. Each patient was invited to receive a home visit from our visit team (either a healthcare assistant [HCA] and advanced nurse practitioner [ANP] or HCA and paramedic). For the patients who consented, the team then performed long term condition (LTC) monitoring blood tests, a diabetic foot check, blood pressure, pulse and weight, where appropriate. A urine albumin/creatinine ratio was taken where patients were able to provide a specimen, or the form and specimen bottle were left with the patient to provide when next practicable. Patients were also offered any outstanding immunisations, such as influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations. This data collection was then followed up by a diabetes clinical review with either myself or the PCN Diabetes Lead Jane Sennett.

Of the 84 patients identified as being housebound or temporarily housebound, four declined the interventions and five died during the review process. The practice was initially unable to contact three of the patients but they were offered the same services at a later date.

OUR FINDINGS

At the time of initial review, one patient was believed to have type 1 diabetes and the remainder had been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. On further review, it was found that the patient who had initially been coded as type 1 diabetes actually had type 2, based on review of history and response to oral therapy. This patient was struggling with insulin therapy and on optimisation was found to be very responsive to a low dose of metformin.

Age and sex

The majority of housebound patients were aged over 80 years, with only one under the age of 50. Among participating patients, 40 were female and 32 were male.

HbA1c

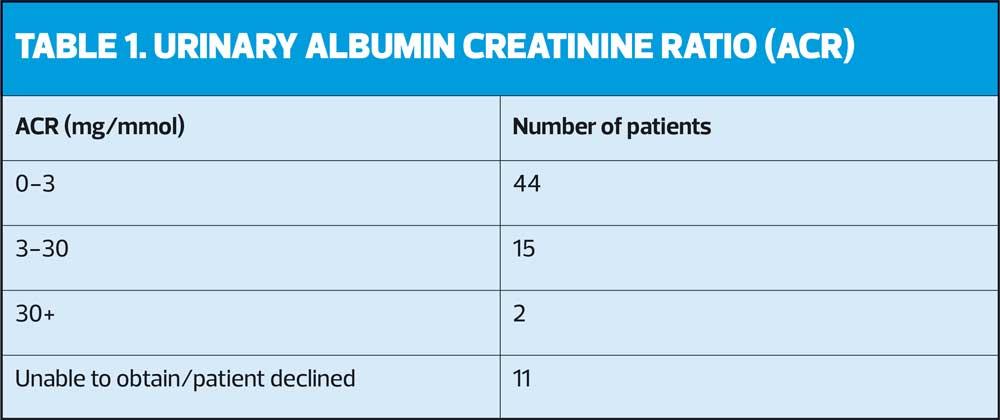

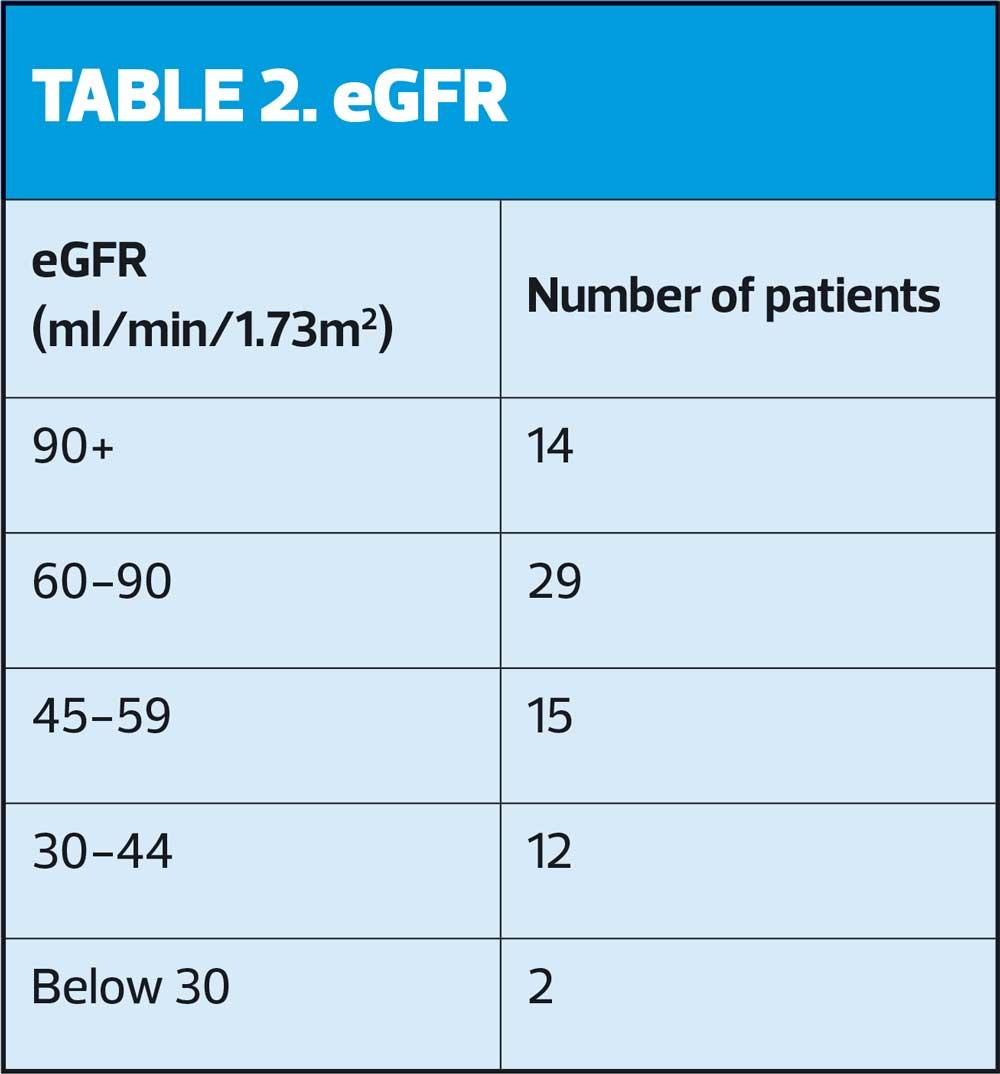

The majority of the 72 participating patients, 54, had an HbA1c level within a satisfactory clinical range, in terms of personalised targets rather than arbitrary thresholds, in line with NICE recommendations. It was important to consider appropriate goals for each patient and involve them in this decision. ACR and eGFR results are shown in Tables 1 and 2.

Multimorbidities

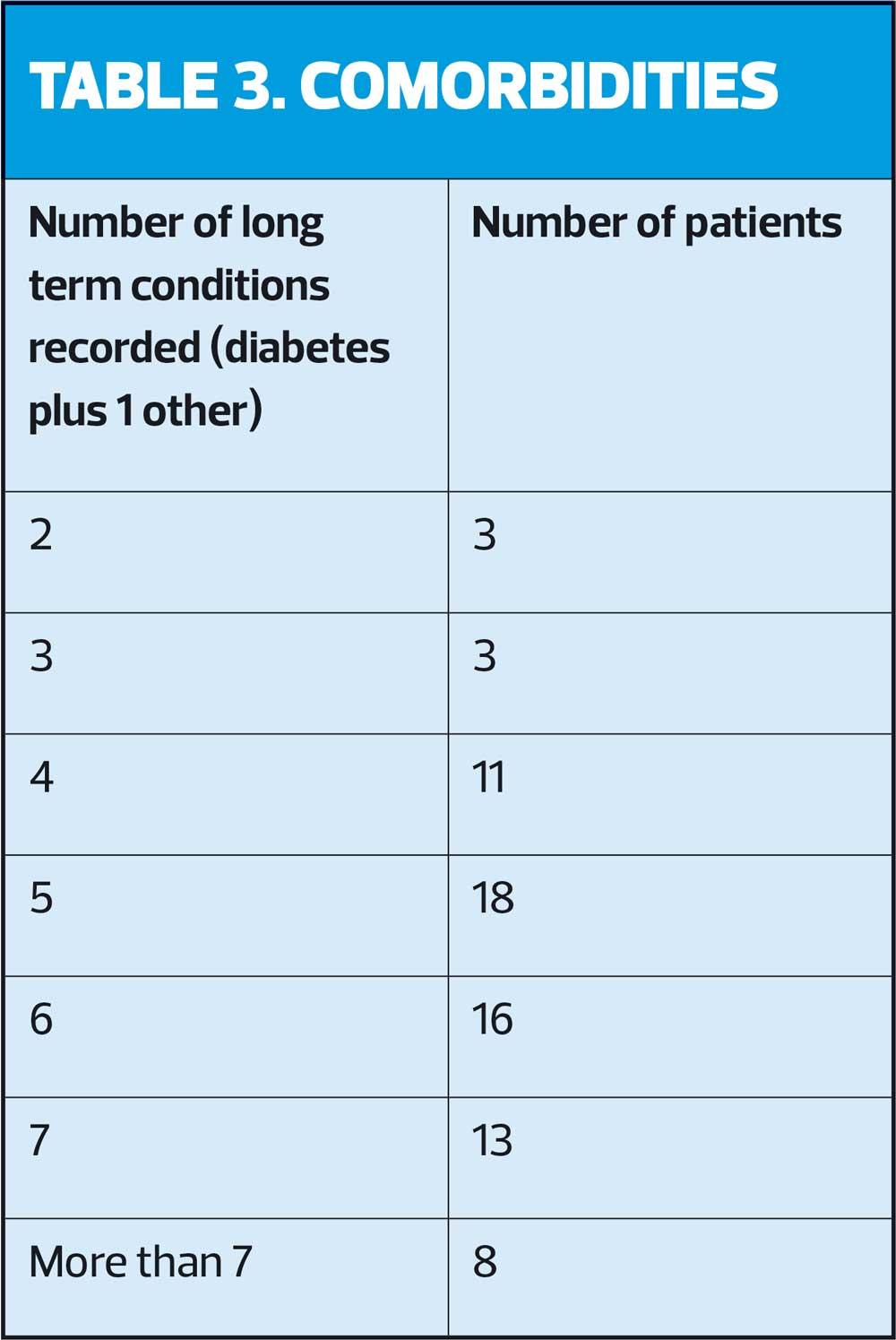

Over three-quarters (76.4%) of patients we reviewed had five or more significant long-term conditions (Table 3). Conditions included all QOF-registered conditions, including being on the learning disability register, any diagnosis of anxiety or depression where pharmacotherapy was prescribed, chronic pain, hypothyroidism and other rheumatic disease not included under rheumatoid arthritis, such as polymyalgia rheumatica. None of the patients had diabetes as a single long-term condition.

Clinical interventions

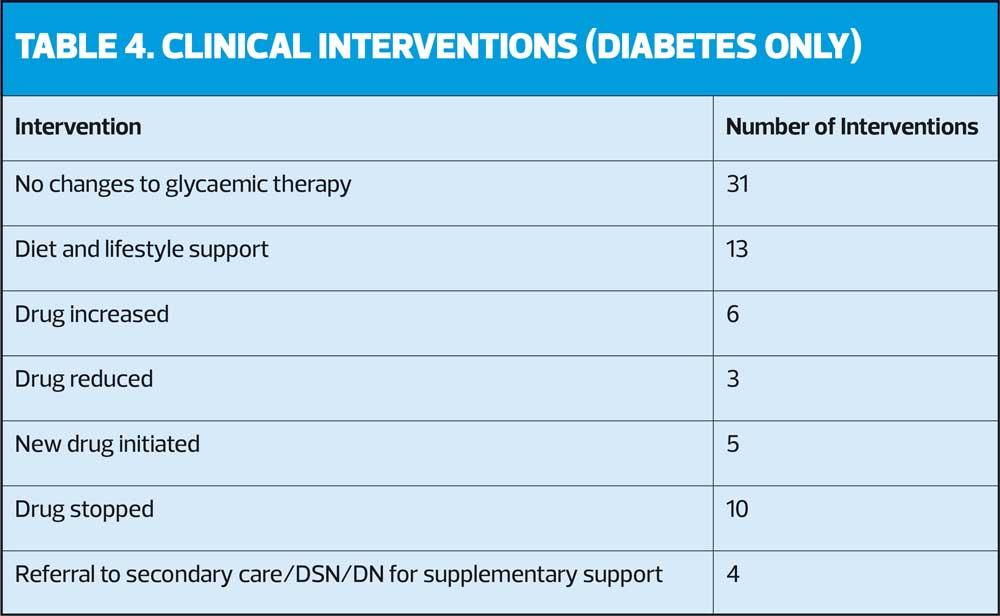

Table 4 shows a brief summary of glycaemic interventions. It does not include other clinical optimisation as due to the complexity of the patients, the data would be very lengthy and outside of the scope of this article. Other interventions not detailed here included inhaler optimisation, optimisation of comorbidities, non-diabetic deprescribing as part of STOPP START guidance, self-care advice, care of acute concerns, and referral to the social prescribing team. The number of interventions exceeds the number of patients as patients may have received more than one intervention at a time.

Blood pressure monitoring

Patients’ blood pressure was recorded as part of the project and reviewed in the context of their age, perceived frailty and based on whether patients were symptomatic of postural hypotension. Of the 72 patients reviewed, nine required adjustment to their current therapy.

DISCUSSION

The concept of the project seemed to be well received by patients and their families. In future, as we develop our multimorbidity model within the practice and PCN I would like to roll this out to all housebound patients with multimorbidity. We need to consider whether timing of review is important; the goal of this project was to be a ‘one-stop shop’ in October and November 2020 for those with diabetes to try and optimise their management before the COVID-19 second wave hit us. Now we have piloted the project, it is likely to be beneficial to bring this forward to late summer/early autumn to ensure (for example) patients with COPD are reviewed and optimised before the temperature drops, and to incorporate the objective of reducing winter pressures with the early roll out of influenza vaccination (and forthcoming COVID-19 vaccination booster) programmes for these vulnerable groups.

The majority of patients with type 2 diabetes seemed to fall into 2 categories: those who were well controlled on little or no pharmacological therapy; and those who were on insulin therapy and struggling to optimise their HbA1c. I feel the former group may have been patients whose type 2 diabetes was conforming to a strict insulin resistance model and whose carbohydrate intake may have reduced over the years in with increasing age. Conversely, the latter group may well have developed insulin insufficiency over time which has worsened with age. This highlights the importance of patient-centred prescribing and considering which diabetes agents should be used in older patients. For example, there will be many patients where the risk of using sulphonylureas and insulin outweighs the benefits (consider falls, risk of hypoglycaemia compared with metformin and DPP-4 inhibitors etc); however, for those who have been developing additional pancreatic insufficiency on top of insulin resistance we should incorporate use of insulin secretagogues and replacement therapy. It is imperative that we work closely with our community Diabetes Specialist Nurses (DSNs) and Integrated Care Team (ICT; community nursing) colleagues to effectively support the complex needs of these patients who may need assistance with administration of injectables and appropriate blood glucose monitoring.

Deprescribing

The main areas of de-prescribing were oral therapies. Metformin was deprescribed where HbA1c was very well controlled and it was felt that the risk of acute kidney injury outweighed the perceived benefit of cardiovascular protection. Gliclazide was deprescribed if its risks to the outweighed its benefits as mentioned above, and a lower risk agent was prescribed instead. Some DPP4 inhibitors were deprescribed where it was felt that pharmacological therapy was no longer needed, or where it was felt to be an inappropriate adjunct to insulin therapy, to minimise inappropriate polypharmacy. Follow up was scheduled as appropriate and safety-netting advice given.

It was unsurprising that the vast majority of patients had satisfactory blood pressure results. A significant number were receiving optimal therapies for heart failure (ACE inhibitors or angiotension receptor blockers [ARBs]) and beta blockers. In addition, personalised BP targets for patients living with frailty would likely to be less stringent, to minimise the risk of falls and hospitalisation.

A successful multimorbidity approach should always consider medications used for multiple indications. One example of this would be using ACE inhibitors for hypertension,7 heart failure,8 and renoprotection in chronic kidney disease.9 Given the recent development of new expanding licences for SGLT2 inhibitors such as dapagliflozin for heart failure10 and canagliflozin for renal disease as well as type 2 diabetes,11 I was expecting to find lots of patients who would potentially benefit from these therapies. However, I did not initiate a significant amount of SGLT2 inhibitor therapy.

As described to above, the majority of patients were either well controlled without heart failure or significant renal disease, or were already very frail. This latter group would have been difficult to rationalise the use of SGLT2 therapy so late in their disease progression, and the risk of dehydration and acute illnesses may have outweighed any potential benefit at this stage.

There is a challenge ahead considering the paucity of evidence in these much older patients, and the potential for conflict where, for example, diabetes specialist nurse teams and heart failure nurse teams may have different priorities. We have a duty of care to approach the prescribing of such medications from a patient-centred, rather than disease-centred perspective. Thinking holistically about activities of daily living, patient expectations and risk of hospitalisation with or without the adjunctive therapy, we need to ask ourselves what we are trying to achieve. I believe the complexity of these decisions highlights the importance of an MDT approach, including input from secondary care, which I hope to see normalised as part of the emerging integrated care systems.

DISCLAIMER

The data collection and review project was supported by a grant provided by Napp Pharmaceuticals. Napp did not have any involvement in the data collection, review or the publication.

REFERENCES

1. Barron E, Bakhai C, Kar P, et al. Associations of type 1 and type 2 diabetes with COVID-19-related mortality in England; a whole-population study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2020;8(10):813-822.

2. Rawshani A, Alansson Kjölhede E, Rawshani A et al. Severe COVID-19 in people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes in Sweden: A nationwide retrospective cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021 May;4:100105. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100105

3. Curtis LR, Price HC. Meeting the challenges of housebound patients with diabetes. Practical Diabetes 2018 Mar/April: 55-57a.

4. Riley S, Ainslie KEC, Eales O, et al. High prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 swab positivity and increasing R number in England during October 2020: REACT-I round 6 interim report. medRxiv Nov 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.30.20223123.

5. Havant Borough Council. Havant Borough Profile 2018. https://cdn.havant.gov.uk/public/documents/Havant%20Borough%20Profile.pdf

6. Diabetes UK. Diabetes in the UK 2012: Key statistics on diabetes. https://diabetes-resources-production.s3-eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/diabetes-storage/migration/pdf/Diabetes-in-the-UK-2012.pdf

7. NICE NG136. Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136

8. NICE NG106. Chronic heart failure in adults: diagnosis and management; 2018. Available from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng106

9. NICE CG182. Chronic Kidney Disease in adults: assessment and management; 2014 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg182

10. McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2019; 381:1995-2008.

11. Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2019; 380:2295-2306.