Managing type 2 diabetes: When is it time for insulin?

Judy Downey

Judy Downey

RGN, BSc(Hons)

Independent Diabetes Nurse Consultant, Hammersmith, London

The emergence of newer glucose-lowering therapies in recent years may delay the use of insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes (T2D), but there is still a place for insulin in the management of T2D, either alone or in conjunction with other drugs

In this article we will reflect on the place for insulin in the management of type 2 diabetes, its use concurrently with other diabetes therapies, and finally the evidence informing the clinician that the use of basal analogue insulin, may be the preferred choice when initiating insulin in many casesType 2 diabetes (T2D) is a chronic condition characterised by many years of increasing insulin resistance, which may commence up to 15 years prior to diagnosis.1

At the point of diagnosis, the beta cells in the pancreas can no longer secrete sufficient insulin to overcome resistance to insulin, leading to rising blood glucose. The resulting uncontrolled hyperglycaemia leads to micro vascular (retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy) and macro vascular complications (cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease and peripheral arterial disease). The benefits of timely and intensive management of hyperglycaemia, thereby reducing the risk of micro- and macro-vascular complications are now well established.2 Evidence demonstrates that at all points during the treatment pathway, continual reinforcement of diet and lifestyle measures should be continued, as this is the bedrock of all types of T2D management, irrespective of oral or injectable pharmacotherapies.3

Newer therapies for individuals with established cardiovascular disease (CVD) or at high risk of cardiovascular disease, or chronic kidney disease (CKD) which now can also be used in combination with insulin therapy, form a more recent part of the treatment paradigm. For many people with T2D insulin therapy will be required eventually, nevertheless initiating insulin treatment is often seen as a last resort not only by people with poorly controlled diabetes, but also by health care professionals (HCPs).4

The UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) changed practice in the UK by demonstrating that no matter how diabetes is managed, there is a progressive deterioration in glycaemic control, as measured by HbA1c.5 Data from UKPDS confirmed that this deterioration is slowed down when individuals are commenced on metformin therapy at diagnosis. Before the publication of the UKPDS in 1998, metformin had been a little-used therapy, but it has since been established as the first line initial monotherapy recommendation in all national and international guidelines.

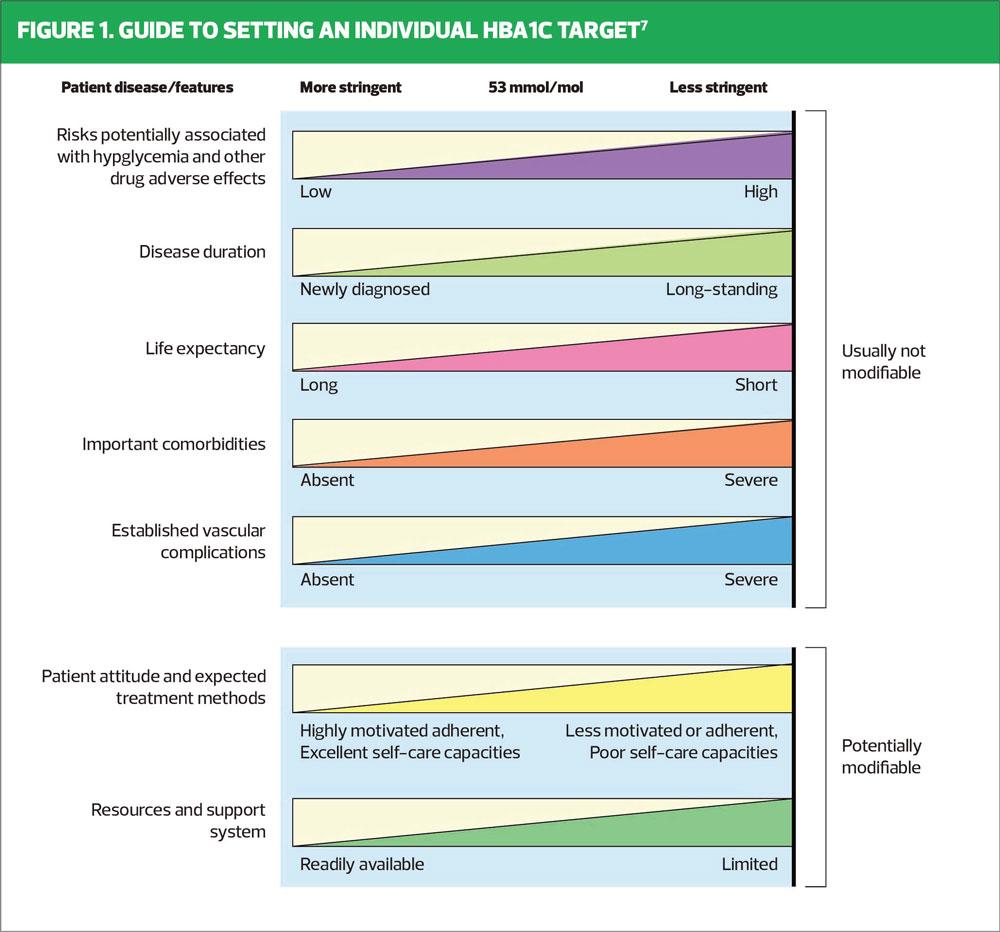

Some clinicians believe that introducing metformin concurrently with lifestyle advice at diagnosis may mean that people do not see diet and physical activity as an integral part of their management, but it is important that the powerful effect of lifestyle change is emphasised at every encounter thereafter. Studies have also shown that there is a ‘legacy effect’ or metabolic memory, where if early, tight glycaemic control is maintained for at least 2 years after diagnosis, this may confer long-lasting microvascular and macrovascular benefits, even if the glycaemic control deteriorates over the following years.6Although NICE guidance states that an HbA1c target of 48 mmol/mol should be aimed for when initiating therapy, the clinician should take into account a range of modifiable and non-modifiable factors when setting the HbA1c target.3 As seen in Figure 1, avoidance of hypoglycaemia is a crucial part of this decision-making process. NICE recommends adding in a second oral agent if the HbA1c target is not met after 6 months,3 but individualisation of HbA1c target is essential at all stages of the treatment pathway, including when an individual is using insulin therapy.

WHEN TO CONSIDER INSULIN IN TYPE 2 DIABETES

NICE guidance states that insulin therapy should be considered if the blood glucose levels are inadequately controlled despite dual or triple therapy, for individuals who cannot tolerate oral antidiabetic drugs, or if they are contraindicated.3

NICE recommendations3

- Offer intermediate (NPH) insulin injected once or twice daily according to need

- Consider starting both intermediate and short acting insulin (particularly if the person’s HbA1c is 75 mmol/mol [9.0%] or higher).

- Consider using insulin detemir or insulin glargine, as an alternative to intermediate insulin if:

- The person needs assistance from a carer or healthcare professional to inject insulin, and if use of these preparations would reduce the frequency of injections from twice to once daily, or

- If the person’s lifestyle is restricted by recurrent symptomatic hypoglycaemic episodes, or

- If the patient would otherwise need twice daily intermediate insulin injections in combination with oral glucose lowering drugs.3

Consider pre-mixed (biphasic) preparations that include short acting insulin analogues, rather than pre-mixed (biphasic) preparations that include short acting human insulin preparations, if:

- The patient would prefer to inject insulin immediately before a meal, or

- Hypoglycaemia is a problem, or

- Blood glucose levels rise markedly after meals.3

Consider switching to insulin detemir or insulin glargine from intermediate insulin in adults with T2D:

- Who do not reach their target hba1c because of significant hypoglycaemia, or

- Who experience significant hypoglycaemia on intermediate insulin irrespective of the level of hba1c reached, or

- Who cannot use the device needed to inject intermediate insulin but who could administer their own insulin safely and accurately if a switch to one of the long acting insulin analogues was made, or

- Who need help from a carer or HCP to administer insulin injections and for whom switching to one of the long acting insulin analogues would reduce the number of daily injections.

BARRIERS TO COMMENCING INSULIN THERAPY

Patient barriers

Individuals are understandably concerned regarding the process of injecting themselves with insulin. When insulin therapy is the next step in the treatment algorithm, it is very helpful for the HCP to work through with the person any possible barriers that apply to them. These might include:

- Fear of injecting

- Concern that using insulin means that diabetes is more serious

- Fear of hypoglycaemia

- How to use the injection device

- The reaction of friends and family

- The effect on daily life

- Fear of gaining weight

- Driving when using insulin therapy

By ascertaining an individual’s fears before initiating insulin therapy, the HCP can more effectively provide the support needed to enable an individual to take on this significant step in their self-management.

Clinician barriers

Clinical inertia has been described as a barrier that may become evident when a clinician is considering addition of insulin, especially for people with diabetes who are new to insulin, or insulin-naïve.8 We know that glycaemic control is likely to deteriorate if initiation of insulin is delayed, followed by lack of dose adjustment and delayed intensification. The reasons why HCPs may postpone insulin initiation are many: inexperience with insulin initiation and managing insulin regimes, coupled with lack of time and resource, may contribute to clinical inertia. The clinician should be very aware of the concerns of the person with diabetes, but if these concerns are addressed before the insulin is initiated, the process will become smoother for both the clinician and patient.8

We know that insulin treatment in T2D supplements the insulin still being produced by the beta-cells, its role being to lower blood glucose to prevent hyperglycaemia and prevent or delay microvascular and macrovascular complications. Ideally, clinicians should inform people with T2D soon after diagnosis that insulin therapy may be needed as part of their future management, so that when insulin becomes necessary it is not seen as a failure of self-management or as a punishment for non-adherence.

COMPETENCIES NEEDED TO INITIATE INSULIN IN PRIMARY CARE

All HCPs involved in the prescribing, dispensing and administration of insulin must access regular training. NICE states that ‘insulin therapy for people with T2D should only be initiated and managed by HCPs with relevant expertise and training’.3 CCGs may commission accredited training provided by university departments, or they may provide an in-house accredited programme, some of which are provided as a service by pharmaceutical companies. It is crucial that all HCPs initiating and managing insulin complete the free e-learning module Six steps to insulin safety in addition to attending an accredited insulin module.9 The recommendations made by the Forum for Injection Technique are vital reading for all clinicians involved in insulin initiation and management, and can be downloaded from its website.10

Choosing an insulin regime

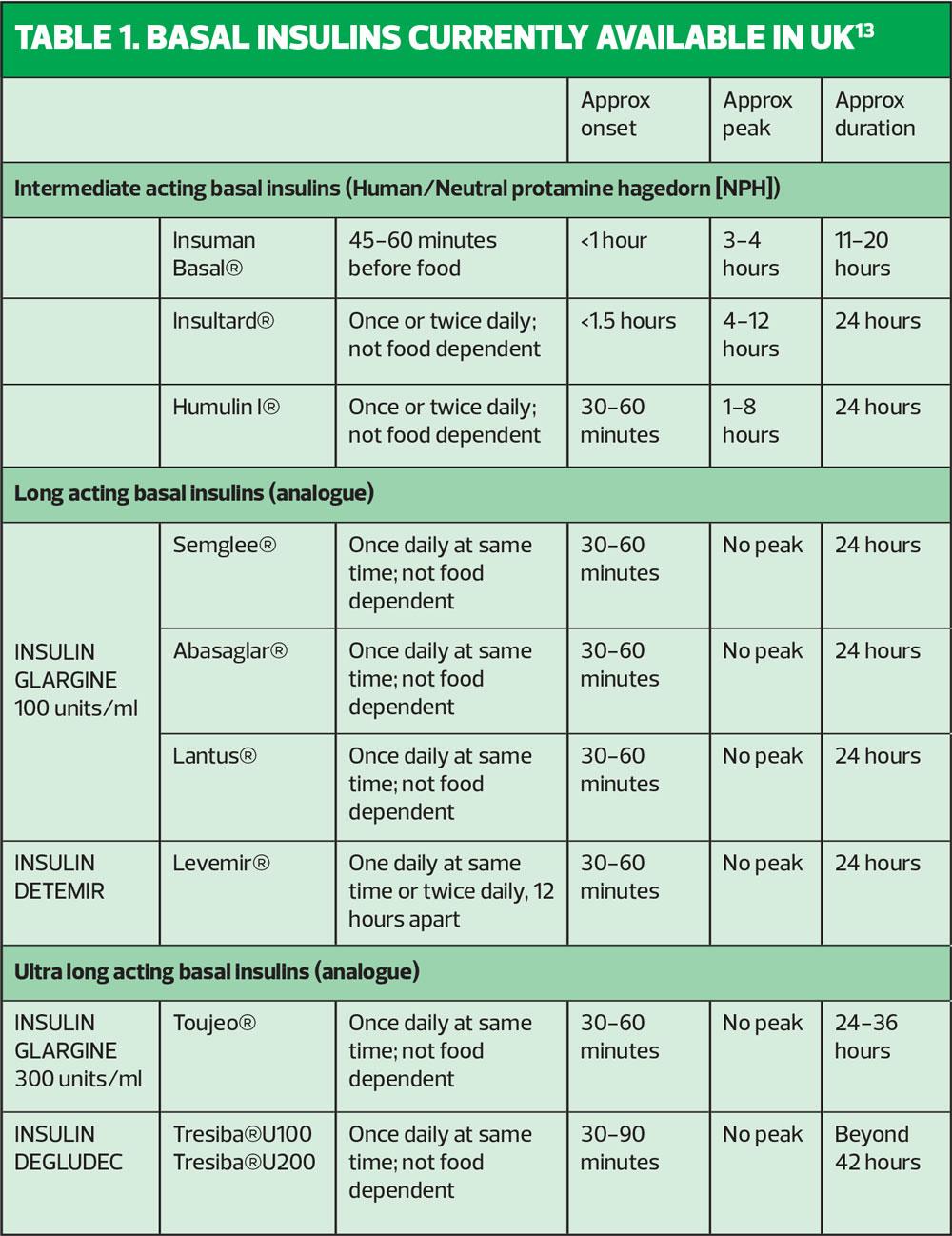

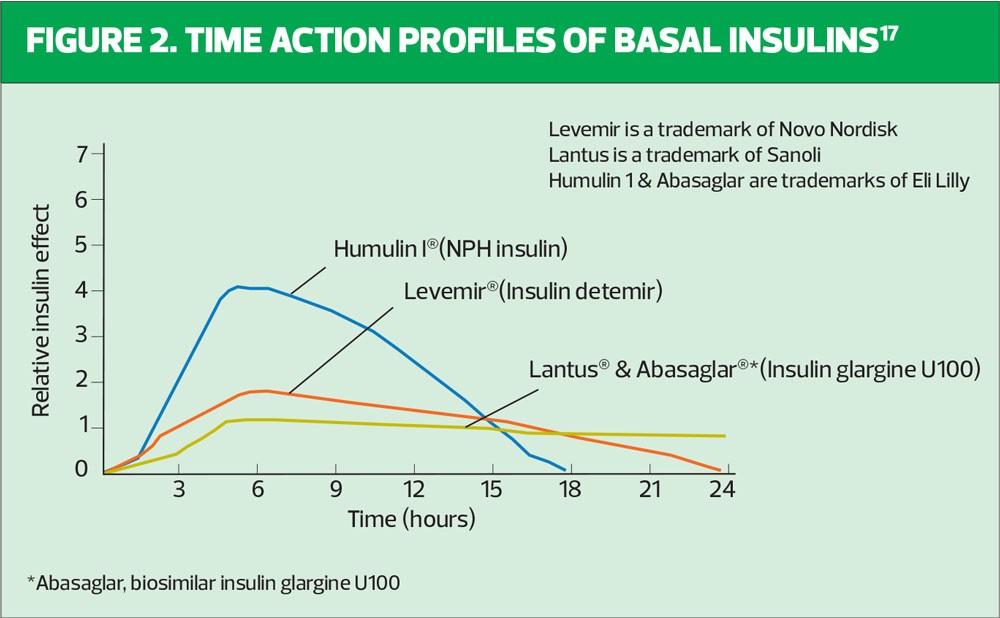

When deciding on an insulin regime for an individual using insulin for the first time, the clinician should consider the time-action profiles of the different insulin preparations available (Table 1, Figure 2). We know that NICE guidelines recommend commencing insulin-naïve people on an intermediate-acting human insulin such as Insulatard®, Humulin I® or Insuman Basal®. Human, or neutral protamine hagedorn (NPH) insulin is a synthetic insulin manufactured by recombinant DNA technology – the name ‘human’ can be misleading. Human insulin is available as short-acting and intermediate-acting. Both of these preparations promote weight gain, as many individuals report that they feel very hungry, leading them to snack, thereby minimising occurrence of hypoglycaemia, which is a great fear for many individuals. Intermediate or isophane insulin has peak activity 5–7 hours after injecting and can last 13–18 hours.11 Typically, patients are advised to inject in the late evening, once a day. Guidance from the Royal College of Nursing recommends a starting dose of 10 units for once-daily regimens. Starting low and giving clear insulin titration guidance over the following months will build the person’s confidence and your own.12 The start dose, if injected in the evening, is up-titrated against the capillary fasting blood glucose obtained the next morning. It is important the person with T2D is encouraged to self-titrate to achieve target fasting blood glucose levels, which are agreed with the clinician.

There are limitations associated with NPH insulin, including:

- Variable absorption

- Unwanted peaks of action overnight

- Insufficient duration of action

- Needs to be injected at the same time every day

- The need to mix thoroughly before injecting.14

As shown in Figure 2, intermediate insulin peaks after 5–7 hours, which may result in nocturnal hypoglycaemia if the insulin is injected before bedtime. If nocturnal hypoglycaemia is considered to be a particular concern for an individual, the HCP is wise to consider initiating using a basal analogue insulin such as glargine (Lantus®), insulin detemir (Levemir®) or the biosimilar insulin glargine (Abasaglar®) to provide a more constant delivery of insulin over a 24 hour period. This will minimise the possibility of nocturnal hypoglycaemia when the insulin dose is injected at bedtime.

An additional benefit when using analogue basal insulin is that the need to supplement with snacks is reduced, due to less incidence of hypoglycaemia, which in turn will lessen weight gain in the individual.14 This potential steady weight gain can set off a cycle of events –increasing insulin resistance, leading to increased doses of insulin as insulin requirements will also increase in line with the insulin resistance. Treating hypos or eating to avoid hypos also contributes to weight gain in people with T2D.

In circumstances where community nurses are required to inject insulin every day, but where timing of injections is difficult due to workload, a very long acting basal analogue insulin such as insulin degludec (Tresiba®) can be considered, as it lasts up to 42 hours. Insulin degludec has time profile properties which allow once a daily dosage, at any time of the day. Its use is associated with a significantly lower risk of hypoglycaemia.15

INITIATING INSULIN THERAPY IN PEOPLE WHO ARE OVERWEIGHT OR OBESE

Individualisation of care is paramount when treating T2D. There are multiple factors to consider, which include the weight of an individual and also the risk of hypoglycaemia when commencing insulin therapy. The impact of likely weight gain must be taken into account when deciding on the insulin regime as starting insulin is associated with steady weight gain, resulting in the HbA1c target being difficult to reach, as reported by UKPDS study group.5

The continued importance of diet and lifestyle issues should be reinforced when insulin therapy is commenced. There is now a choice of oral and injectable therapies for T2D, which can be used in combination with insulin therapy to mitigate against the unwanted side-effects of insulin – namely weight gain and hypoglycaemia, but which also provide cardiovascular (CV) and renal benefit. Using combination therapy in this way, to improve outcomes following on from insulin initiation in the overweight or obese individual, facilitates the use of the minimum insulin dose to reach the target HbA1c. The ADA/EASD consensus report recommends considering the use an SGLT2 inhibitor and/or a GLP-1 receptor agonist. The use of these therapies in conjunction with insulin will diminish the weight-increasing effect of insulin, thereby keeping the insulin dose lower, whilst conferring CV and renal benefit to the individual.6

CONCLUSION

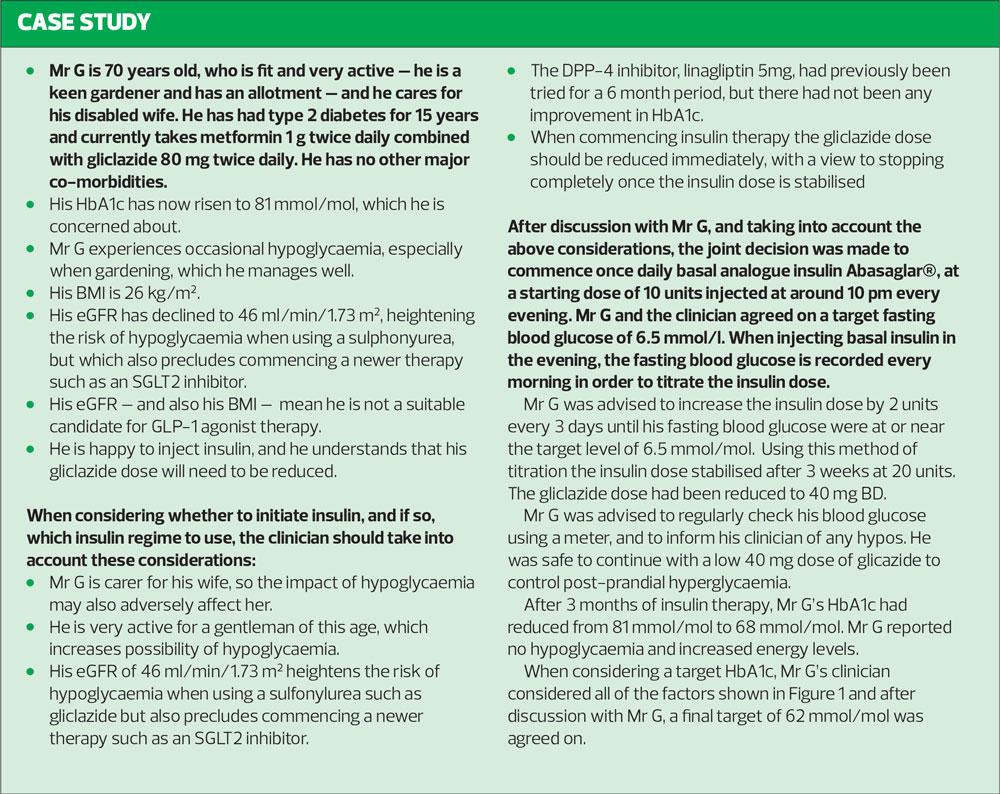

The management of diabetes is becoming ever more complex – lifestyle changes remain the underpinning constant in combination with an ever-expanding number of oral and injectable pharmacological therapies, some of which have proven cardiovascular and renal benefit. The new insulin preparations on the market are more expensive than traditional human insulin, which has been available since 1982. Local and NICE guidelines promote the use of human isophane or intermediate insulin when commencing insulin therapy in type 2 diabetes, as it is considerably cheaper than the analogue insulin preparations. NICE guidance often encourages the use of therapies with the lowest acquisition cost rather than clinically better outcomes. The T2D guideline is currently being updated to reflect latest evidence. In the case of Mr G, using any basal analogue insulin confers a lower risk of hypoglycaemia. Abasaglar® was chosen as it is the basal analogue insulin with the lowest acquisition cost.

The clinician must always consider how different insulin preparations will affect an individual, taking into account duration of action, and the timing of peak insulin action. Analogue basal insulin should be the insulin of choice for individuals where hypoglycaemia is deemed a particular concern, but ultra long-acting basal analogue insulin is particularly useful where community nurses are administering the injections.

Clinicians involved in the initiation and optimisation of insulin therapy must ensure that they are competent in this task by attending accredited study, and by undertaking the Safe Use of Insulin module online. The support of the multi-disciplinary diabetes team should be sought when there any questions or queries regarding insulin therapy for an individual.

REFERENCES

1. Savage DB. Mechanisms of insulin resistance in humans. Hypertension 2005; 45: 828-833

2. Holman RR, et al. 10 year follow-up of glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Eng J Med 2008; 359:157-89

3. NICE NG 28. Type 2 diabetes in adults: management; 2017. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng28

4. Khunti K, Millar-Jones D. Clinical inertia to insulin initiation and intensification in the UK: a focused literature review. Prim Care Diabetes. 2017;11(1):3-12.

5. UKPDS Research Group. UKPDS 16. Overview of 6 years’ therapy of type II diabetes: a progressive disease. Diabetes 1995;44:1249-58

6. Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J et al. ADA/EASD consensus report. Diabetes Care 2018;41(12):2669-2701

7. Inzucchi SE, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: A patient-centered approach. Diabetes Care 2015;38: 140–9

8. Khunti K, Millar-Jones D. Clinical inertia to insulin initiation and intensification in the UK: a focused literature review. Prim Care Diabetes. 2017; 11(1):3-12.

9. Six Steps to Insulin Safety. https://www.diabetesonthenet.com/course/the-six-steps-to-insulin-safety/details.

10. Forum for Injection Technique (FIT) Recommendations. http://fit4diabetes.com/united-kingdom/fit-recommendations/

11. Gadsby R. Insulin initiation in primary care. Diabetes and Primary Care 2007;9(6):338-342

12. Royal College of Nursing. Starting injectable therapy in adults with type 2 diabetes, 3rd edition; 2019 https://www.rcn.org.uk/clinical-topics/diabetes/publications

13. Trend UK. Basal insulin initiation in adults with type 2 diabetes; 2019. https://diabetestimes.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/HCP_Basal_TREND_FINAL-2.pdf

14. Meneghini LF, et al. Insulin detemir improves glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes who were treated with intermediate insulin or insulin glargine. The PREDICTIVE study. Diabetes Obes Metab 2007;9:418-27

15. Kalra S. Clinical use of insulin degludec: Practical experience and pragmatic suggestions. N Am J Med Sci 2015;7(3):81-85

Related articles

View all Articles