Diabetic kidney disease: diagnosis and management in primary care

Dr Robert Lewis

Dr Robert Lewis

MD FRCP

Consultant Nephrologist, Wessex Kidney Centre, Portsmouth, UK

Practice Nurse 2020;50(7):23-27

Early diagnosis of diabetic renal disease helps primary care teams to identify patients with type 2 diabetes who are at particular risk of subsequent cardiovascular disease but there is evidence of room for improvement

As a consultant nephrologist, I am often asked by primary care teams about how diabetic kidney disease (DKD) should be diagnosed and managed. Audit data suggests that surveillance and identification of early DKD could be improved. Furthermore, there have been recent important changes in the recommended management of DKD, which are particularly relevant to primary care teams. With this in mind, I have set out to clarify current advice by giving answers to the questions I am commonly asked.

Q: How is diabetic kidney disease recognised and how does it differ from chronic kidney disease in people without diabetes?

A: DKD is a catch-all term for several damaging effects of diabetes on the kidneys.

Diabetic nephropathy (DN), which is hyperglycaemia-induced glomerular disease, is one important element of DKD. However, hypertension, renal atheroma and ischaemia are also common in diabetes, causing varying degrees of glomerulosclerosis and tubular fibrosis. The relative dominance of these pathologies gives DKD variable clinical features. This is why proteinuria, which is the hallmark of DN, can sometimes be absent in DKD.

Both type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease (CKD) of any cause are fairly common conditions. It is possible, therefore, that they could coexist in an individual without there being a causal link. Furthermore, as noted above, the clinical features of DKD may not always be typical. Accordingly, some judgement is required when attributing renal disease to DKD rather than other, possibly remediable, conditions. Important examples of these include glomerulonephritis, ureteric obstruction and myeloma.

In a person known to have had type 2 diabetes for at least 5 years, with a gradually-rising albumin:creatinine ratio (ACR) followed by a gradually-falling estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) over months or years, particularly if there are microvascular complications elsewhere, it is reasonable to make a presumptive diagnosis of DKD. Regular monitoring will allow re-evaluation to ensure that the condition is following the expected natural history.

A diagnosis of DKD should be re-evaluated if there is rapid onset of heavy proteinuria, an unexplained, unusually rapid fall in eGFR, the presence of non-visible haematuria or the onset of new systemic symptoms. In these circumstances, renal ultrasound should be requested and referral to a specialist may be indicated.

Q: How is proteinuria reliably detected in practice?

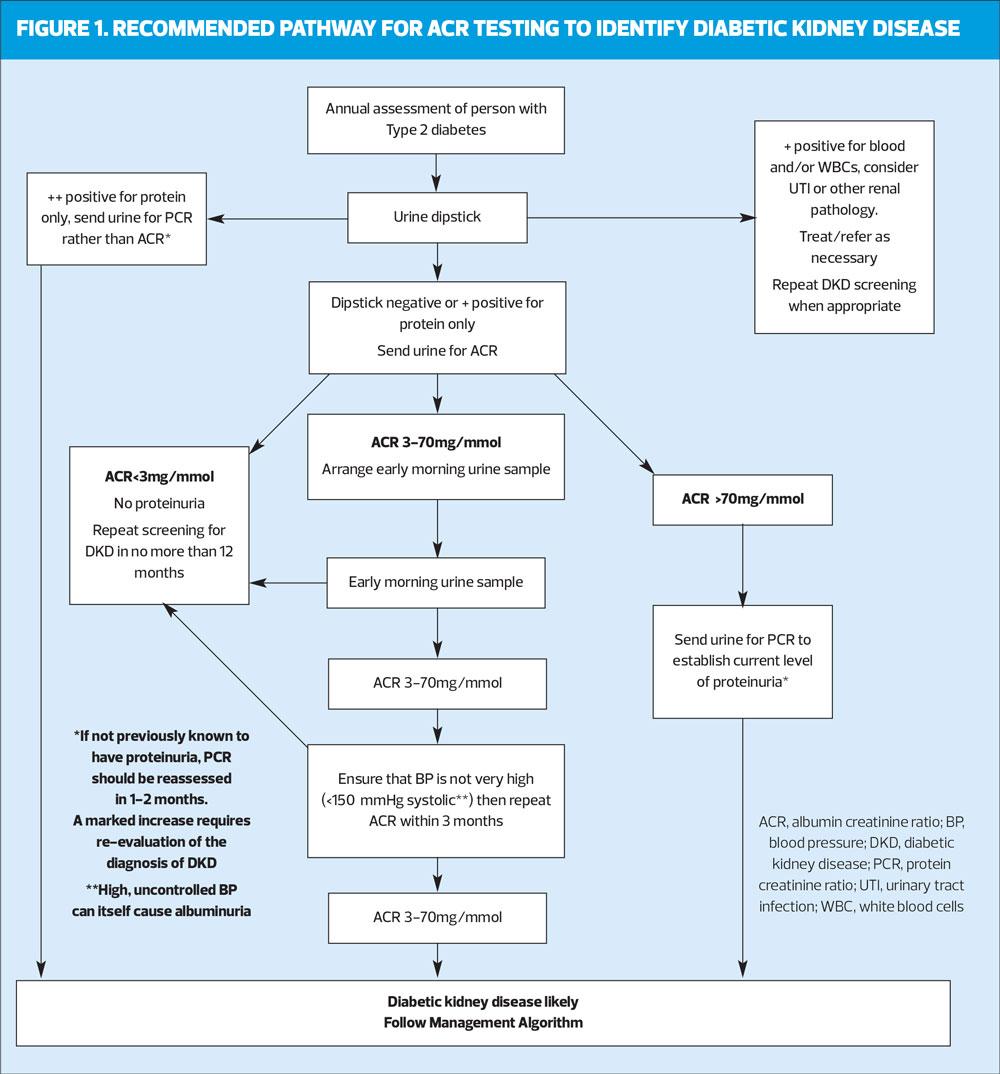

A: The pathway in figure 1 describes how testing for proteinuria should be conducted to ensure that the result is reliable and renal conditions other than DKD are not missed.

Small amounts of protein can appear in the urine after exercise or even being upright and ambulant for a while. For this reason we usually recommend that the ACR is measured on an early morning urine sample (EMU), which consists of urine made when recumbent overnight. This may not always be practical, in which case a fresh random sample of urine can be used for testing. If this shows the ACR to be normal, there is no need to repeat it, but if it is between 3-70mg/mmol, the ACR must be confirmed with an EMU. If at least two early morning ACRs >3 mg/mmol over at least 4 weeks indicate that the high ACR is sustained, the presence of proteinuria is confirmed.

A random ACR >70 mg/mmol cannot be attributable to anything other than significant pathology and a repeat measurement is not necessary to confirm the presence of proteinuria.

Q: How should we respond to a first raised ACR reading?

A: A confirmed ACR above 3 mg/mmol is abnormal in both men and women. Even this low level of proteinuria is associated with risk, so the term ‘microalbuminuria’, which was coined to describe something preceding ‘true’ proteinuria (i.e. when protein is detectable with a urine dipstick), is now effectively obsolete. Significant proteinuria exists when the ACR is >3 mg/mmol.

Proteinuria implies glomerular damage and is usually the first sign of DKD. Detecting it is important, as it is a marker of increased risk of cardiovascular (CV) disease and kidney failure. The 10-year mortality of people with type 2 diabetes who have an ACR >3 mg/mmol is about four times greater than those with a normal ACR.1

An abnormal ACR should prompt rigorous management aimed at mitigating vascular risk. The importance of a healthy lifestyle (smoking cessation, weight reduction and exercise) should be reiterated, and the quality of lipid and glycaemic control re-evaluated.

Blood pressure (BP) control is particularly important and should be treated to a target of <130/80 mmHg, if this can be attained without causing side-effects.2 Because drugs acting on the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) reduce intraglomerular pressure, they have renoprotective properties beyond those due to BP lowering alone.3 They are, therefore, the antihypertensive agents of choice in this group.

In a person with diabetes and proteinuria (ACR>3mg/mmol), either an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) should be commenced and titrated to the highest tolerable dose over a few weeks.

Q: How often should eGFR and ACR be measured in people with DKD?

A: The frequency with which renal biomarkers should be monitored in DKD depends on the severity of renal disease. CKD is classified by eGFR (categories G1 to G5) and ACR (categories A1 to A3). The higher the category for each variable, the greater is the risk of cardiovascular disease and progression of CKD.

According to current NICE guidance, at CKD category G1–G2 (eGFR 60ml/min/1.73m2 and above), the eGFR should be undertaken at least annually.2 At category G3a–G3b (eGFR 30-59ml/min), this should increase to at least six-monthly. Patients at category G4–G5 (eGFR<29ml/min) are often under the care of specialist services and the frequency of monitoring will be determined by individual circumstances, but a check of renal function at least every 3 months is usual.

As long as a patient with diabetes is at ACR category A1 (<3 mg/mmol i.e. normal), the ACR should be measured annually. Once the ACR is abnormally raised, there is no clear guidance on the optimum frequency of measurement. One could argue that, once the presence of proteinuria has been established and appropriate risk management has been undertaken, repeated measurements add little useful information. However, as noted above, the level of ACR correlates directly with CV and renal risk, so accurate risk assessment depends on a comprehensive understanding of the markers of vascular and renal damage. An annual ACR check should, therefore, be done even when the presence of proteinuria has been established.

Q: Should our management change when patients have a higher ACR (>70mg/mmol)?

A: In patients without diabetes, NICE recommends referral of patients with heavy proteinuria (ACR ≥70 mg/mmol) because a significant number of these may have treatable primary glomerular diseases.2 Early diagnosis and intervention is critical.

If the diagnosis of diabetic kidney disease (DKD) is fairly secure and is regularly reassessed (see answer to the first question), patients with an ACR >70mg/mmol can be managed in primary care. Management of cardiovascular (CV) risk in DKD is no different in the presence of heavy proteinuria, except when it is sufficient to cause hypoalbuminaemia and swelling – so-called nephrotic syndrome. This unusual complication of DKD may require specialist referral.

Q: What are the optimum levels of lipids in people with established DKD?

A: A current NICE quality standard for the management of CKD is that patients with renal impairment (of any aetiology) should be offered atorvastatin 20 mg.4

The Association of British Clinical Diabetologists (ABCD)/Renal Association (RA) guidelines recommend that atorvastatin 20 mg should be started in all patients with type 2 diabetes and DKD irrespective of their lipid profile.5 This calls into question the value of using QRISK3 for deciding on lipid management in patients with an eGFR <60 ml/min or proteinuria.

Higher doses of atorvastatin (40–80 mg) may be considered in patients who are at especially high CV risk (e.g. >40 years, poor glycaemic control, poor BP control, etc).5

The lipid profile should be measured annually in DKD. The lipid targets recommended by the ABCD/RA guidelines for patients with DKD are: total cholesterol, 4 mmol/l; low-density lipoprotein (LDL), 2 mmol/l; and non-high-density lipoprotein (non-HDL), 2.5 mmol/l.

Q: Which statin should be used in advanced DKD (eGFR <30)?

A: Atorvastatin remains the statin of choice in patients with DKD and an eGFR <30 ml/min.

However, if it is not tolerated, simvastatin is a safe substitute. Simvastatin is less potent than atorvastatin and may need to be supplemented with ezetimibe to reach lipid targets. This combination has been shown to be effective in CKD.6

Rosuvastatin is effective at lipid-lowering, but it should be avoided in those with DKD (proteinuria or renal impairment) as it may adversely affect renal function.7 Fibrates may be added to statins if required to attain targets, but only in patients who have an eGFR >45 ml/min.

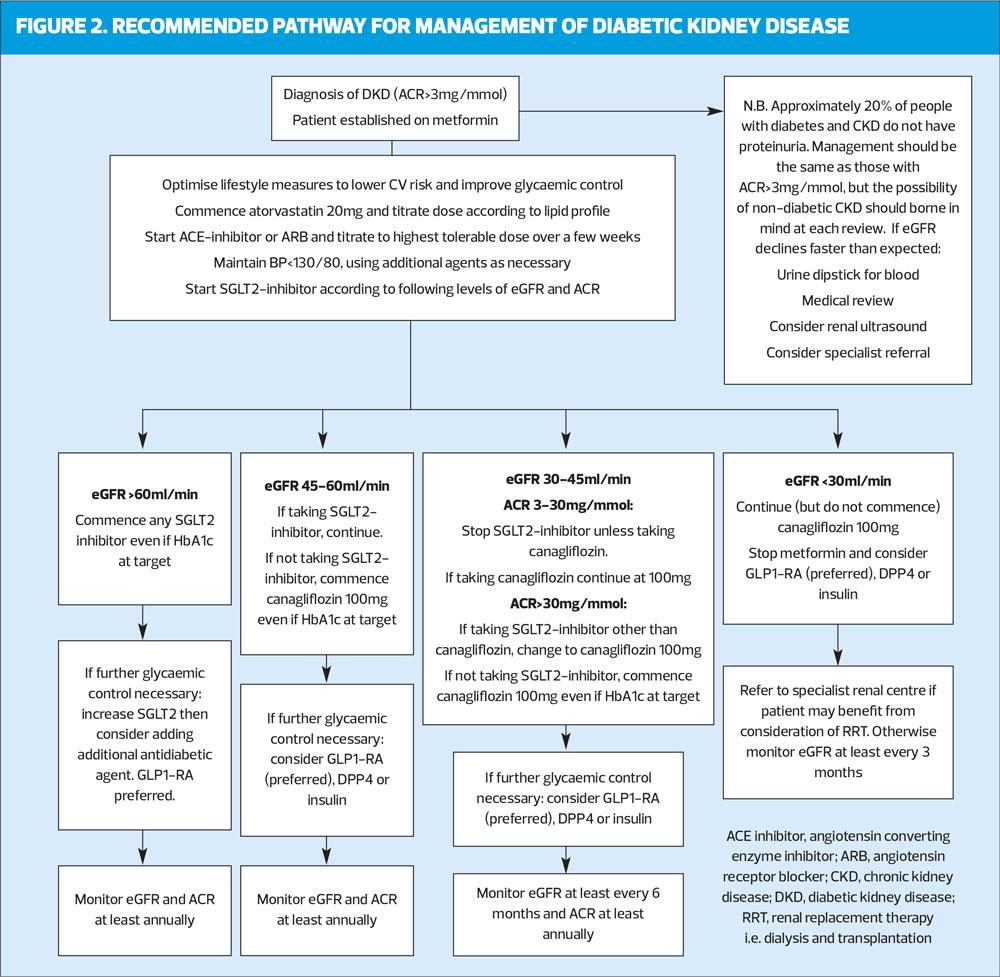

Q: How should SGLT2 inhibitors be used in patient with DKD?

A: The arrival of sodium–glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors has had a major impact on how people with diabetes should be treated. It is likely that their use in patients with DKD will increase in future.

Large trials (EMPA-REG, CANVAS and DECLARE-TIMI) have shown that SGLT2 inhibitors significantly improve major CV outcomes, especially heart failure, when added to standard care (which includes optimal renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system [RAAS] blockade).8 Secondary outcomes from these trials showed additional beneficial effects on DKD. This prompted a number of studies looking specifically at renal outcomes. Only one has reported so far: the CREDENCE study showed that in patients with established DKD (eGFR 30–90 ml/min/1.73m2 and ACR>30mg/mmol) receiving optimal current care including RAAS inhibition, canagliflozin significantly slowed progression of renal impairment and reduced the risk of end-stage renal failure by 32%.9 The study was stopped early after an interim analysis revealed the extent to which canagliflozin improved outcomes. These findings have prompted great interest amongst nephrologists; they cannot be explained by the glucose-lowering effects of these agents (which is small in advanced CKD), so studies are now in progress to see if SGLT2 inhibitors may have similar benefits in non-diabetic CKD.

The growing body of evidence that SGLT2 inhibitors slow CKD progression and improve CV outcomes in patients with DKD led the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) to recommend in their consensus statement that an SGLT2 inhibitor (or glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist [GLP-1 RA]) is the preferred option for patients who have DKD whose glycaemia is not controlled by metformin alone.10 This advice was updated in 2020 following publication of the CREDENCE trial, to recommend that people established on metformin who have either DKD or heart failure should be offered SGLT2-inhibitors in preference to other agents, independently of HbA1C.11

The findings from the CREDENCE study have prompted recent changes to the licence for use of canagliflozin. Whilst other SGLT2 inhibitors are not licenced for initiation in people with an eGFR <60ml/min/1.73m2, canagliflozin can now be commenced in people with diabetes who have an eGFR 45-60ml/min if their diabetes remains suboptimally controlled with metformin alone (or if metformin is not tolerated). Furthermore, if they have significant proteinuria (defined as an ACR>30mg/mmol), canagliflozin can be commenced when the eGFR is in the range 30-45ml/min. Once commenced, the agent can be continued as DKD advances, even to end-stage renal failure. At these low levels of renal function, the glucose-lowering effect of canagliflozin is small, but the marked impact on progression of CKD, cardiovascular risk and heart failure shown in the CREDENCE trial justify its continuation.

It remains to be seen if studies with other SGLT2-inhibitors, which are currently in progress, will show similar benefits to those now confirmed with canagliflozin and if similar licence changes are made for other agents in the class.

REFERENCES

1. Afkarian M, Sachs MC, Kestenbaum B, et al. Kidney disease and increased mortality risk in type 2 diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol 2013;24:302–8

2. NICE CG 182. Chronic kidney disease in adults: assessment and management; 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG182

3. Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, et al. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2011;345: 861–9

4. NICE QS5. Chronic kidney disease in adults. Quality statement 3: Statins for people with CKD; 2011, updated 2017. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs5

5. Mark PB, Winocour P, Day C. Management of lipids in adults with diabetes mellitus and nephropathy and/or chronic kidney disease: summary of joint guidance from the Association of British Clinical Diabetologists (ABCD) and the Renal Association (RA). Br J Diabetes 2017;17: 64–72

6. Baigent C, Landray M, Reith C et al; SHARP Investigators. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with simvastatin plus ezetimibe in patients with chronic kidney disease (Study of Heart and Renal Protection): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2011;377:2181–92

7. de Zeeuw R, Anzalone DA, Cain VA, et al. Renal effects of atorvastatin and rosuvastatin in patients who have progressive renal disease (PLANET 1): a randomised clinical trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015;3(3):181-90

8. Zelniker TA, Wiviott SD, Raz I, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors for primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcome trials. Lancet 2019;393:31–9

9. Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al; CREDENCE Trial Investigators. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2019;380:2295–306

10. Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A consensus report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2018;41:2669–701

11. Buse J, Wexler DJ, Tsapas A, et al. Update to: Management of Hyperglycemia in Type 2 Diabetes, 2018. A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 2020;43(2):487–493.

Related articles

View all Articles