The aged skin and skin tears

ELIZABETH MERLIN-MANTON

ELIZABETH MERLIN-MANTON

RGN, MSc, TVN

Independent Tissue Viability Nurse

Over time the skin structure degenerates, leaving it more vulnerable to skin tears. Knowing how to minimise the risk of skin tears and how to manage them effectively are key skills for the practice nurse with wound care responsibilities

ANATOMY AND PHYSIOLOGY

The skin is one of the largest organs of the body and it has multiple roles, with protection being one of its most important functions. Temperature regulation and sensation are other key functions. A change in the skin’s equilibrium of moisture, temperature or pH levels can lead to a reduction in its ability to protect by either erosion or the skin becoming dry and fragile.

The epidermis, dermis and subcutaneous layers are the three mains layers of the skin, each having their own particular functions, appendages and cells.

- The epidermis is an impervious layer of dead cells, which protects against bacterial assault and water loss or damage.1

- The dermis comprises proteins, collagen and elastin, which provides strength and elasticity, and the epidermis is attached to the dermis at the dermoepidermal junction.

- The subcutaneous layer, or hypodermis, provides padding for protection and ranges in thickness across the body: it is commonly particularly thin on the forearms and tibial crest (shin).

AGEING SKIN

Over time, the skin structure degenerates and its ability to respond successfully to external damage reduces. As the skin becomes thinner the risk of damage is increased. The overall thickness of the skin starts to reduce from the age of 65, with the intrinsic factors being a reduction in hydration, lessening of collagen and degeneration of the elastic fibre network.2 Ultraviolet radiation causes extrinsic ageing, resulting in greater deterioration in the areas more often exposed to the sun. Medical history, including the use of topical or oral steroids or anticoagulants, and previous or current dermatological conditions also have an impact on the strength of the skin. Intrinsically weakened, the strength of the dermoepidermal junction declines, increasing the risk of separation or tearing.

The term dermatoporosis is becoming commonly used to encapsulate both the symptoms of aged skin, such as the reduction of aged skin’s ability to protect, and environmental factors.3,4 It is important for the clinician to be aware of dermatoporosis, which in itself is classed as a predisposing risk factor for skin tears.3,4

SKIN TEARS

The principles for skin tear prevention and management comprise assessment, classification, management with the appropriate dressing and prevention of further trauma.5

Skin tears are acute, traumatic wounds that are caused by shear, friction and/or blunt forces, often on the extremities of older people, resulting in the separation of the layers of skin.6,7 They can be partial thickness, separation of the epidermis from the dermis; or full thickness, separation from the underlying structures.6,7

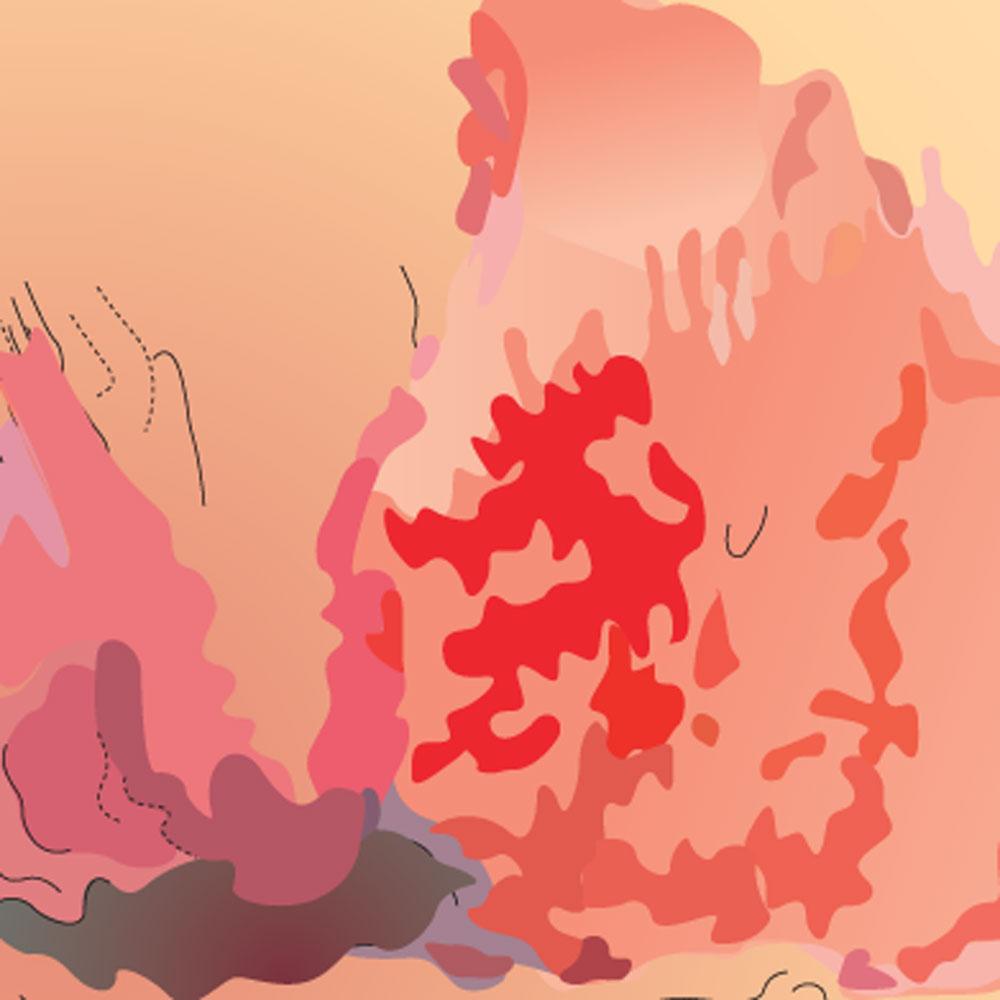

Risk factors for skin tears are summarised in Box 1. The focus on skin tears is usually in the ageing population, yet they are also common skin injuries in infants and neonates whose skin is immature, and when epidermis and dermis cohesion is not robust. In neonates, skin tears are typically associated with devices or adhesives,8,9 and can occur on the head and face as well as extremities.8

The figures for prevalence rates of skin tears in the UK are outdated but elsewhere it has been reported that skin tears are as common or more common than pressure ulcers.1,7 A systematic review of five studies found that reported skin tear rates range dramatically from 2.23% to 92% in the long-term care environments.10 This underlines the need to ensure that local uniform and fingernail policies are adhered to, to minimise the risk to frail and fragile skin.9,11 Moving and handling policies in healthcare settings should also be observed to avoid shear and friction, with specific consideration given to the durable materials used for items such as slings, as these have high potential to cause skin tears in vulnerable patients.

CLASSIFICATION

Although Payne and Martin developed a classification system for skin tears in 1993, and other techniques have evolved or their work has been adapted, none are collectively recognised or widely used.

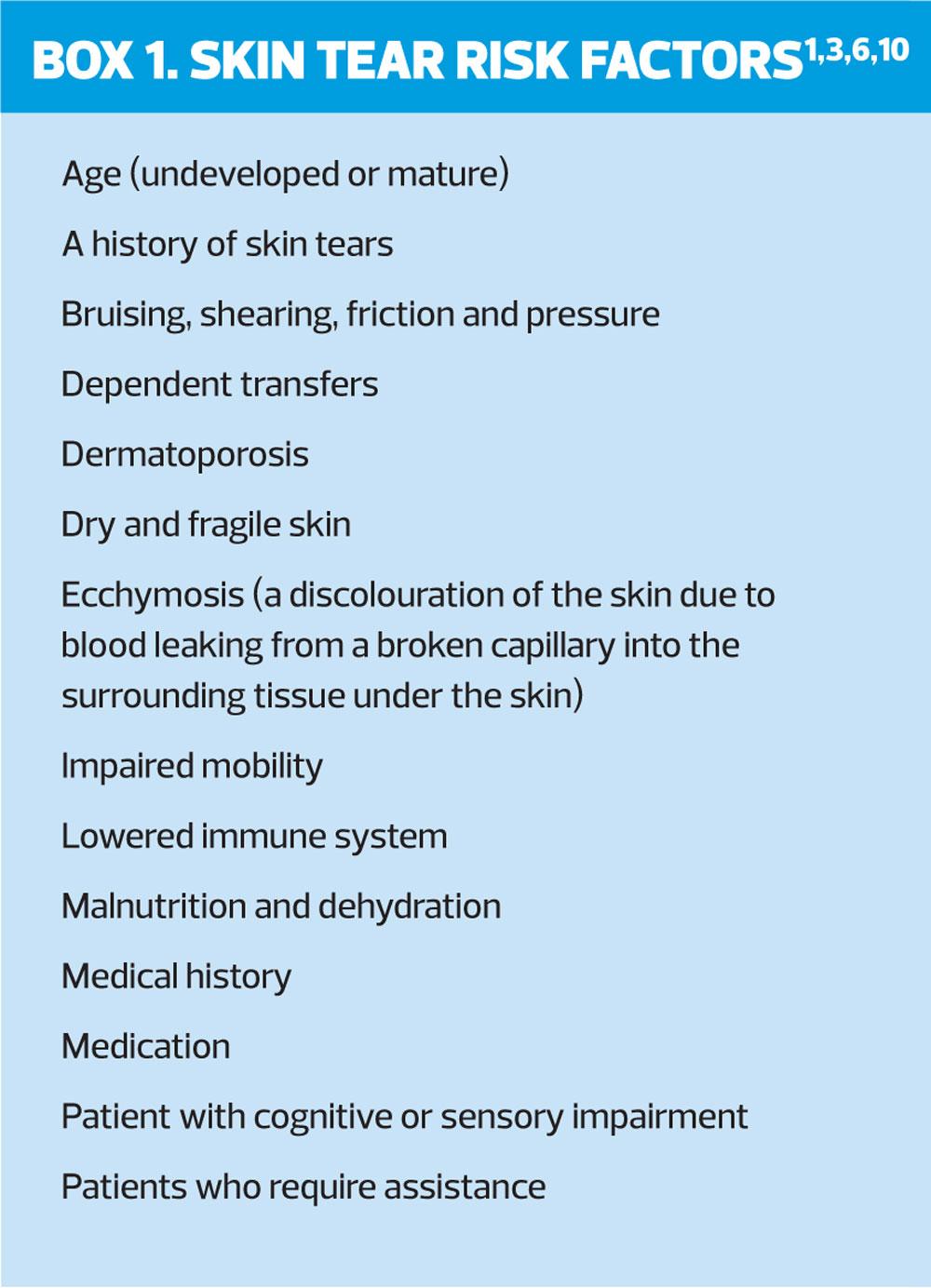

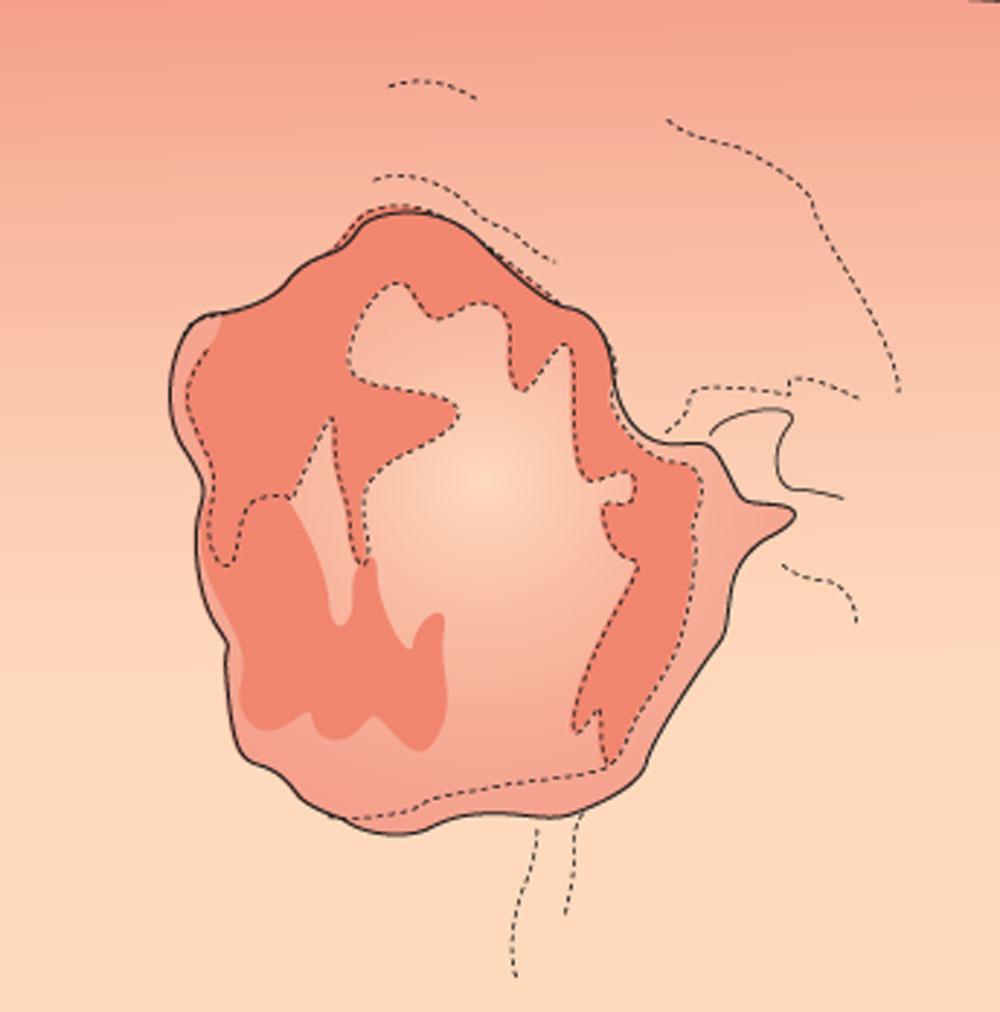

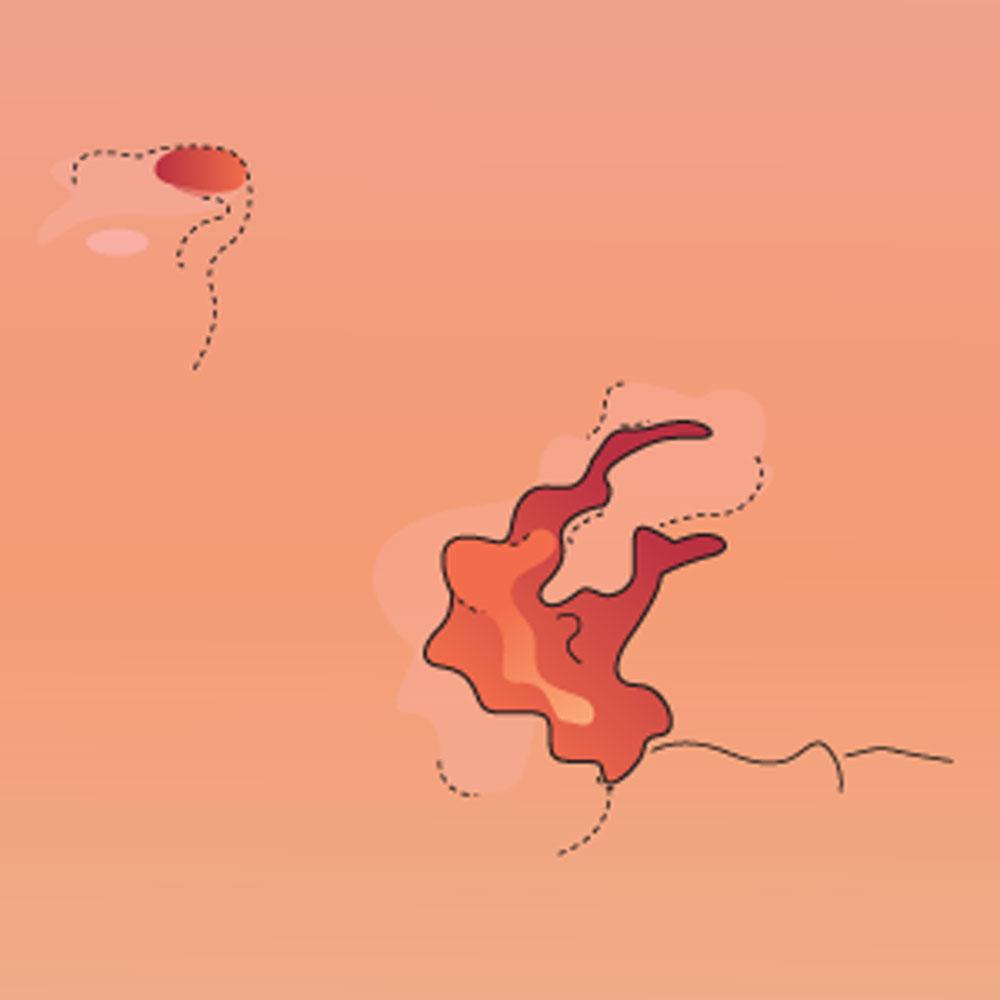

More recently, Carville and colleagues12 created the Skin Tear Audit Research (STAR) classification system, based on the Payne and Martin tool. This STAR classification system additionally considers the colour of the skin and the skin flap, therefore each category is subdivided into 2. (Figures 1 - 5)

The International Skin Tear Advisory Panel (ISTAP) classification system13 consists of only three categories or types, and was created with aim of achieving a common language for all to comprehend.

- Type 1: No skin loss – Linear or flap tear that can be repositioned to cover the wound bed.

- Type 2: Partial flap loss – Partial flap loss that can’t be repositioned to cover the wound bed.

- Type 3: Total flap loss – Total flap loss exposing the entire wound bed.

Individual trusts may have developed and use their own classification system, however, the intention of a classification system is to ensure that there is a standardised process of documenting the severity of a skin tear, allowing for equity of care for all patients across the Trust.

WOUND ASSESSMENT

As skin tears are acute wounds they have the potential to progress along the correct healing trajectory and heal within an appropriate period of time. However, a thorough assessment to identify any risk factors that may interrupt the healing process is required as many of the skin tear risk factors correlate to risk factors that have the ability to delay wound healing.

Accurate measurement of the wound surface area, consisting of depth, length and width, documented in the patient notes, is invaluable to assess effective wound healing. Additionally, with patient consent, a wound image should be considered, in line with local policy.

After the skin tear has been categorised, according to the local classification system used, other areas of consideration are tissue type and whether the wound is infected or at risk of becoming infected. The wound tissue types fall into five general categories although there are several other tissue type descriptors that are used. The percentage of necrotic, sloughy, infected, granulating or epithelialising tissue present should be observed and recorded at each dressing change. Documentation of the skin flap and what percentage of it is viable tissue is also useful.

For any risk of infection, the wound infection continuum should be observed to correlate any signs and symptoms present with the infection continuum stage. The stages consist of contamination, colonisation, local infection, spreading infection and systemic infection.14 It is recognised that all wounds are contaminated and colonisation occurs but usually no direct treatment is required. If a local infection develops a topical antimicrobial is recommended, which is then coupled with systemic antibiotics for any signs of a spreading or systemic infection. Immuno-compromised patients may not have visible signs of an infection, hence all patients require a holistic assessment.

With skin tears, there is an accompanying risk of haematomas being present or forming which need to be documented as part of the initial wound assessment. Furthermore, it is imperative that the condition of the peri-wound skin is assessed and recorded to highlight any fragility or risk of further trauma. This allows planning and consideration of appropriate dressing selection, to avoid unnecessary additional damage.

MANAGEMENT

Once a skin tear has occurred, any bleeding needs to be controlled by applying pressure and/or elevation of the effected limb, followed by cleansing the wound and removal of any debris as per the local guidelines. The skin tear categorisation is deciphered and subsequently

re-approximation of the skin flap should be carried out, without undue stretching. If the flap requires rehydration, consider using a moistened swab for 5-10 minutes as this has the potential to enhance the possibility of reapproximation.9 To protect the peri-wound area, consideration of a skin barrier product to reduce the risk of maceration from exudate and/or an emollient to reduce the risk of further skin tears is essential.9 A truly non-adherent dressing should then be applied with a suitable secondary dressing.

Additionally, a tetanus vaccination should always be a consideration,15 and depending on the severity of the tear, a specialist referral may be required. If there is involvement of underlying structures consider referring to the plastic surgery or surgical team. If appropriate, refer the patient to a falls team to minimise the risk of further trauma. The patient’s pain level should be recorded using a visual analogue scale (VAS) and the pain controlled.

DRESSING SELECTION

The range of advanced wound care dressings available is evolving rapidly. Skin tears, as with all wound types, can result in a complex, chronic wound if the correct treatment is delayed. The most suitable dressing can only be decided upon once the aim of the treatment has been determined and the condition of the surrounding skin has been ascertained. Suitable dressings range from silicone dressings, technology lipido colloid (TLC) dressings, impregnated mesh dressings, hydrofibre dressings and foams, with or without an adhesive border.15-17 All dressings that increase the risk of further trauma should be avoided. Although glue has been noted to be suitable for use for skin tear closure,5,17 wound closure strips, sutures and staples are not recommended because of the vulnerability of the patient’s skin and the risk of further damage being caused.16

To prevent interruption of the wound healing process by disturbing the skin flap on removal of the dressing, a directional arrow should be drawn straight onto the dressing surface. This gives clear guidance to the clinician, as to the safest direction for dressing removal.

Due to the fragility of the surrounding skin, it may not be possible to use a bordered dressing even with a gentle adhesive, therefore a non-adherent primary contact dressing secured with a retention bandage is recommended, ensuring that this is applied well with no risk of bandage damage. The optimal dressing should be easy to apply, with pain free, atraumatic removal, provide the ideal moist wound healing environment, and form a barrier to bacteria.

SUMMARY

Understanding the effects of ageing on the skin is important and early identification of the ‘at risk’ patient provides an opportunity to maintain skin integrity and reduce skin tear occurrences. Providing patient information and guidance on good skin care is essential and an important element of skin tear prevention. Full holistic assessment is crucial and effective wound assessment with thorough documentation informs clinicians as to whether the progress is satisfactory or being hindered. Skin tear categorisation informs and guides clinicians and, coupled with all-inclusive assessments, are central to providing optimum care.

REFERENCES

1. Benbow M. Assessment, prevention and management of skin tears. Nursing Older People 2017; 29(4):31-39. doi:10.7748/nop.2017.e904

2. Kozarova A, Kozar M, Minarikova E, Pappova T. Identification of the age related skin changes using high-frequency ultrasound. Acta Medica Martiniana 2017;17(1):15-20. doi:10.1515/acm-2017-0002

3. Vanzi V, Toma E. Recognising and managing age-related dermatoporosis and skin tears. Nursing Older People 2018;30(3):26-31. doi:10.7748/nop.2018.e1022

4. Re Domínguez, et al. Dermatoporosis, an emerging disease: case report. Our Dermatol Online. 2016;7(2):191-194

5. Ellis P. Skin tears: Causes and management. Nursing and Residential Care 2018;20(3):130-135. doi:10.12968/nrec.2018.20.3.130

6. Jones ML. Fundamentals of tissue viability, 1.5. skin care: Preventing skin tears. British Journal of Healthcare Assistants 2017;11(5):230-232. doi:10.12968/bjha.2017.11.5.230

7. LeBlanc K, Baranoski S, Christensen D, et al. International skin tear advisory panel: A tool kit to aid in the prevention, assessment, and treatment of skin tears using a simplified classification system. Advances in Skin & Wound Care 2013;26(10):459.

8. Nist et al. Skin rounds: a quality improvement approach to enhance skin care in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Advances in Neonatal Care 2016;16(Suppl 5): S33-S41

9. Ellis R, Gittins E. The All Wales Guidance for the Prevention and Management of Skin Tears, 2015. Wounds UK. http://www.welshwoundnetwork.org/files/8314/4403/4358/content_11623.pdf

10. Strazzieri-Pulido K, Peres GR, Campanili TC, et al. Incidence of Skin Tears and Risk Factors: A Systematic Literature Review. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2017;44(1):29-33

11. McInulty L. Prevention and management of skin tears in older people. Emergency Nurse: The Journal of the RCN Accident and Emergency Nursing Association 2017;25(3):32-39. doi:10.7748/en.2017.e1687

12. Carville K, Lewin G, Newall N, et al. STAR: A Consensus for Skin Tear Classification. Primary Intention 2007;15(1):18-28. http://www.woundsaustralia.com.au/journal/1501_03.pdf

13. LeBlanc K, Baranoski S, International Skin Tear Advisory Panel, 2013. Skin tears: Best practices for care and prevention. Nursing 2014;44(5):36-46. doi:10.1097/01.NURSE.0000445744.86119.58

14. Swanson T, Angel D, Sussman G, et al. International Wound Infection Institute; Wound infection in clinical practice. Wounds International 2016. http://www.woundinfection-institute.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/IWII-Wound-infection-in-clinical-practice.pdf

15. Baranoski S, LeBlanc K, Gloeckner M. CE: Preventing, assessing, and managing skin tears: A clinical review. Am J Nursing 2016;116(11):24. doi:10.1097/01.NAJ.0000505581.01967.75

16. Deeth M, Stephen-Haynes J. The prevention, assessment and management of skin tears. Practice Nurse 2016;46(6): 32.

17. LeBlanc K, Baranoski S, Christensen D, et al. The art of dressing selection: a consensus statement on skin tears and best practice. Adv Skin wound Care 2016;29(1):32–46

Related articles

View all Articles