Validating the diagnosis and management of COPD patients

RUTH THOMAS

RUTH THOMAS

RGN, BSc Nursing Practice

Advanced respiratory nurse, AIRS Clinic and Whaddon Medical Centre, Milton Keynes

ERICA HAINES

RGN, OHN Dip, MSC cert Advancing Clinical Practice

Lead nurse and respiratory specialist nurse, Redhouse Surgery, Bletchley

Practice Nurse 2022;52(3):18-22

Accurate diagnosis of COPD is essential, but many patients remain undiagnosed or misdiagnosed: a real time qualitative primary care based study related to the validity of the diagnosis and management of patients on COPD registers in general practice

Asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) share many characteristics and symptoms, and the differential diagnosis between the two diseases can be difficult in primary care. Accurate diagnosis of asthma and COPD relies on taking an in-depth history, performing quality assured spirometry with correct interpretation and assessing response to trials of therapy, often with repeat spirometric testing. These are essential as correct treatment of both can improve overall quality of life, reduce the frequency and severity of exacerbations and reduce mortality.

It is suggested that up to two-thirds of people with COPD remained undiagnosed and there are therefore ‘missing millions’ yet to be identified, who are at risk of morbidity and mortality, or potentially misdiagnosed as asthma.1 This research supported a review undertaken to assess COPD services in Milton Keynes (MK) which found that COPD prevalence was below the national figure at that time, (1.2% and 1.48% respectively) with COPD mortality rates 40% above national figures and that of comparator councils. In part it was considered that this related to lack of disease-specific COPD training in primary care health staff resulting in misdiagnosis, misclassification of COPD in practice disease coding systems and lack of COPD support available in some primary care practices from, for instance, Respiratory Nurses.

Further to this research, in 2011, use of a COPD data collection tool allowed a more in-depth analysis of respiratory management of half the registered patient population of Milton Keynes at that time (130,837 patients) from 11 out of 27 general practices with varying demographics.

This tool identified that accuracy of spirometry and subsequent reliability of COPD diagnoses were very variable with 46% of patients on COPD registers having no evidence of airflow obstruction or inaccurately interpreted spirometry.2 Of those, 66.3% had an MRC of 1 or 2 and were over-prescribed therapy according to the NICE guidance at the time, with over 33% of those prescribed inhaled corticosteroids.

The study found that 4.49% on the COPD register were receiving oxygen therapy although only 10.59% had any documentation of pulse oximetry, and were missing vital information regarding severity of their condition and possible need for referral for an oxygen assessment or further investigation. However 16% of those recorded with MRC 4 or 5 had normal spirometry, suggesting misunderstanding of this stratification system, inaccurate coding, or alternative unknown diagnoses. Only 26% had smoking pack history documented, an important risk factor for COPD development and 483 patients (2.7%) were on dual COPD and asthma registers suggesting poor history taking, probable misdiagnosis, inappropriate prescribing and potential over treatment of some patients. Prescribing data was difficult to interpret because of the use of inhaled steroids for both asthma and COPD with 7% prescribed unlicensed ICS monotherapy without any LABA.

As a result of the above, funding for one-day spirometry and six month COPD diploma training was arranged by Milton Keynes (MK) CCG and MK Public Health. Funded training, also followed by the relaunch of trust-wide COPD and Bronchiectasis self-management plans, was delivered face-to-face in practices and included features of exacerbations, their prevention, differential diagnoses, and pharmacological and non-pharmacological management. Like many other Trusts, MK CCG provided training sessions focused on inhaler technique, following a study which suggested that healthcare professionals lacked sufficient knowledge to educate their patients.3

In addition to this, funding was provided for the development and use of a standardised COPD template, a new respiratory formulary and specialist nurse mentorship in practices.

A subsequent BLF study in 2019 found that the number of people who have ever had a diagnosis of COPD has increased by 27% in the last decade, suggesting that more undiagnosed cases are being found, possibly as a result of widespread training and awareness of the condition, or that the disease is becoming more common, though changes in record-keeping could also be a factor.1

OBJECTIVES

Publication of the Right Care Respiratory Focus Pack4 highlighted five key issues in Milton Keynes:

- Higher prescribing costs for COPD and asthma

- Higher mortality from COPD in patients <75years

- Higher costs for emergency admissions associated with respiratory conditions

- Adult emergency admission were 68 per 100,000 (significantly higher than peer group comparators, at 42 per 100,000)

- Higher than average length of stay (excess bed days) for flu/pneumonia

Based on QOF 2015/16 data there was an under-prevalence of asthma, reported as 5.5% versus the national average of 5.9%, and COPD prevalence was equivalent to the national average at 1.6%; however Right Care findings suggested there may be underlying diagnostic and management issues.

This study therefore aimed to address accurate diagnosis of asthma and COPD, cost effective evidence based prescribing, and disease management.

METHODS

Initially it was hoped that a whole-time equivalent respiratory nurse/clinical pharmacist-led service would address misdiagnosis of COPD and asthma, identify appropriate patients for medication switches in an effort to reduce prescribing costs, optimise patient management plans and help increase knowledge and skill levels of primary care health care professionals in the management of obstructive lung disease. Further aims of the plan were to ensure asthma and COPD management plans are in place and support smoking cessation.

However, the CCG was unable to recruit a pharmacist and the two respiratory nurses who undertook the project (the co-authors), had very limited dedicated time available. It also became apparent that due to poor quality testing and interpretation of spirometry plus coding issues the audit tools had limited value. The project was extended from 6 to 10 months, and the focus switched to validating GP registers to ensure accurate diagnosis and Read coding before optimising treatment regimes. Confirmation of diagnoses would be the only route to real cost savings with reduction of morbidity and mortality.

Limited project time directed the authors to review every set of notes held on COPD registers of those practices with the highest COPD admissions, equating to one third of the CCG practices. Registers were checked for quality of diagnostic spirometry where tests existed, subsequent spirometric testing for quality, objective and subjective response to therapy trials and re-coded diagnoses where indicated.2,5-7

Three key respiratory prescribing areas were approached to ensure that prescribing is evidence based, effective, and cost effective with the particular aims of:

1. Step down appropriate COPD patients on triple therapy to dual therapy removing inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and where possible save money by switching brand of tiotropium therapy.

2. Step down asthma patients on high dose ICS/LABA or switched to alternative lower dose ICS/LABA inhaler, in line with the British Asthma Guideline.6

3. Ensure accurate diagnosis and correct coding of asthma and COPD.

RESULTS

Spirometry

Diagnostic spirometry should always be performed post bronchodilator when the patient is clinically stable to avoid false low readings leading to a misdiagnosis of irreversible airflow obstruction.2

Despite provision of numerous CCG-supported spirometry study days over the past decade for all clinicians involved in the care of respiratory patients, diagnostic spirometry tests were found to be of poor quality, with up to 43% found to be non-reproducible, not performed post bronchodilator or inaccurately interpreted.7 In part some of the findings may be due to staff changes and retirement with no succession planning for respiratory care within those practices.

Similar findings from the Welsh COPD Audit found 81% of spirometry tests were not recorded as post bronchodilator,8 though it is important to note that quality of traces in that audit were not analysed, which is important when determining the presence or absence of obstructive lung disease and therefore accurate COPD diagnoses and precise prevalence figures.

Diagnostic spirometry and subsequent repeat testing in one practice was performed during consultations for acute exacerbations, resulting in consistently false low values leading to erroneous COPD diagnoses. It was noted this surgery appeared to have poor uptake of annual review invites, so opportunistic testing may have been the only option. The disadvantage of this approach is that these tests then only demonstrate the airflow limitation expected during exacerbations and do not offer any valuable differential diagnostic information, such as variability of airflow obstruction seen in asthma.

It was noted that many spirometry traces were not corrected for ethnicity resulting in false predicted values and inaccuracy of results. Furthermore FEV1 was often recorded as litres/min flow rate and not %predicted values, the latter of which is necessary to determine the severity of airflow obstruction.9

Over-reliance on spirometer print out reporting ‘good blows’ led to erroneous COPD diagnoses when checking the corresponding time volume curves. In many cases the FVCs were actually short blows resulting in misleading reduced FEV1/FVC ratios.

Inaccurate interpretation was further magnified when %predicted value was documented in place of FEV1/FVC ratio when determining presence of airflow obstruction, again falsely increasing diagnosis of irreversible airflow obstruction seen in COPD.

Reversibility tests were frequently found to have less than the minimum of 15 minutes between pre and post bronchodilator, necessary to determine positive results which may indicate underlying asthma.

Subsequent normal spirometric testing of these patients highlighting large decrease/increase in values did not appear to result in a challenge the COPD diagnosis once it had been coded in the notes, despite no history of recurrent respiratory symptoms or in some cases documented resolution of those symptoms without any inhaled therapy.

Modified Medical Research Council dyspnoea scale (mMRC), exacerbation frequency and asthma co-diagnosis were similar between these two groups held on the COPD register, both as likely to receive inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and long-acting beta2 agonist (LABA) therapy, despite ICS not being indicated for COPD except in specific circumstances.2

This suggests concordance issues, COPD misdiagnosis or existence of a co-morbidity requiring referral for investigation.

History taking

Documentation at diagnosis and follow up reviews frequently lacked any history of duration, pattern or frequency of symptoms, smoking pack years, recreational drug use, occupational exposures, or exacerbation history. Many diagnoses were based on a history of smoking and cough without any objective testing or referral for suspected pathology. Symptom history and enquiring about past or present exposure to animals, birds, occupational and noxious substances are important because they may indicate other causes for symptoms and warrant referral for further investigations.10,11

There was rarely any history recorded at initial diagnosis regarding common co-morbidities such as gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), dysfunctional breathing, cardiac symptoms, pulmonary embolus or pneumonia.

GORD is a common comorbidity which has significant correlation with COPD exacerbations,12 so identifying and treating this important symptom may reduce morbidity and need for rescue steroids, which in turn may increase reflux and need for further medical treatment. Use of a validated questionnaire13 identified its co-existence in 35.8% of those patients analysed, of whom 41% were receiving anti-reflux therapy, leaving almost 60% with untreated reflux and at increased risk of exacerbations.

Approximately 20% of those on the COPD registers studied included differential diagnoses of ischaemic heart disease, heart failure, asthma, bronchiectasis, interstitial lung disease, asbestosis, sarcoidosis, dysfunctional breathing patterns, obstructive goitre and GORD. Of note, 2% on the register were found to have undiagnosed lung cancer.

Nissen et al14 found that concurrent asthma and COPD diagnosis (ACOS) appeared to affect only a minority of patients and that asthma diagnoses were over-recorded in people with COPD. This is contrary to results of this research, which found final COPD registers reduced and both asthma and ACOS registers increased.

Pharmacological management

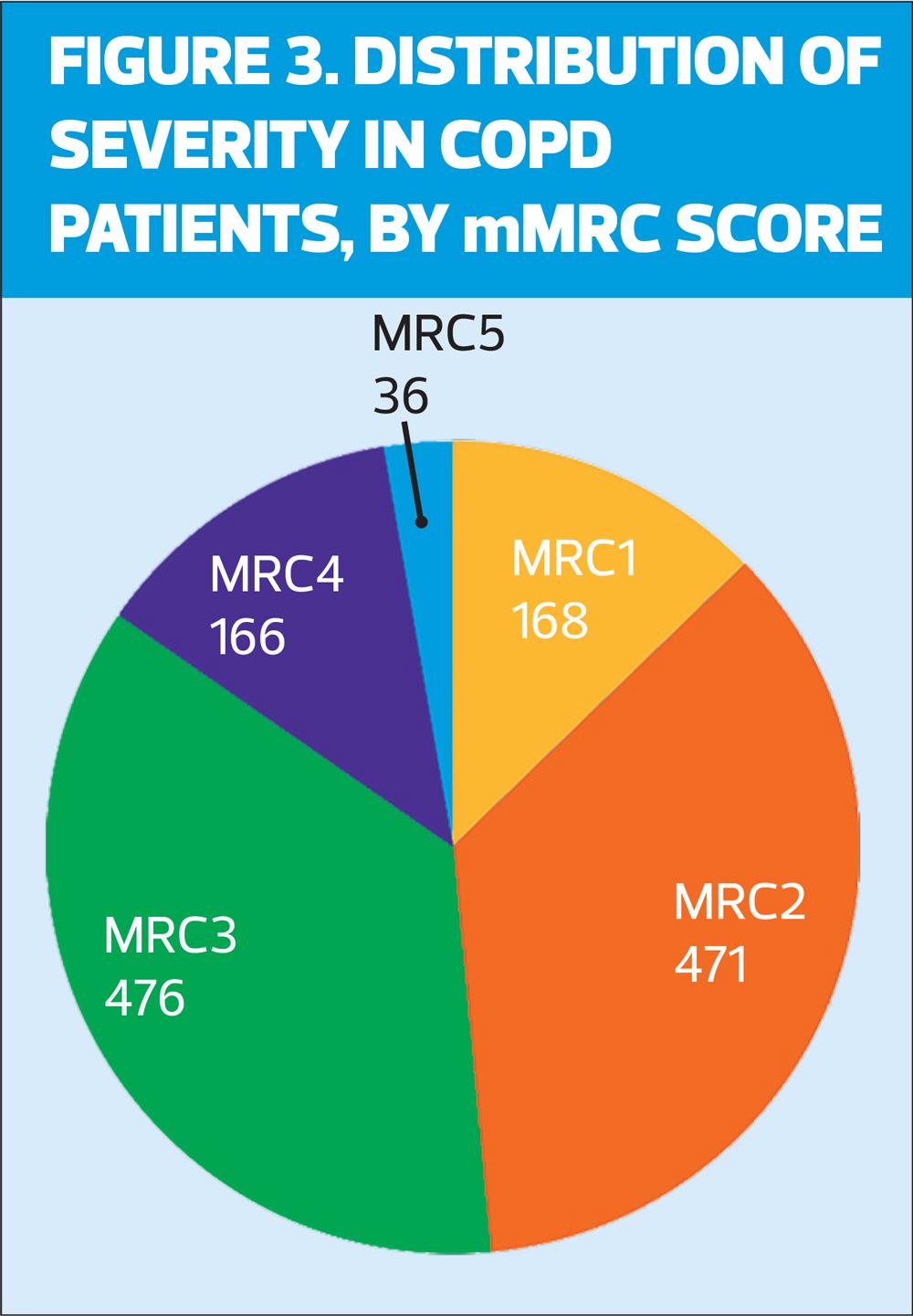

There were a number of issues relating to prescribing including use of unlicensed doses of ICS/LABA in COPD, used frequently in those with an mMRC 1 or 2, which accounted for 53.9% of the COPD register. This suggests over-prescribing in this group and increased risk of adverse side effects, including pneumonia. Anecdotally, it was noticed that there was higher incidence of pneumonia in one practice with high dose ICS/LABA usage.

There was a large variation in concordance with inhaled therapy in patients with both COPD and asthma, irrespective of once daily or twice daily dosing regimes.

Montelukast and antihistamines were prescribed for patients with no history of atopic disease or documented benefit since commencing them. Those prescribed methylxanthines rarely had monitoring of serum levels, necessary to identify therapeutic levels and so maximal benefit in terms of reduction of breathlessness.

Little documentation of self-management advice, importance of activity, disease process and the role of inhalers in the management of obstructive lung disease was found, which arguably are as important as pharmacotherapy.

This audit showed that very few patients had received advice about physical activity. Of those eligible for pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) 44.3% had no record of any discussion regarding PR or physical activity.

Of the 678 who were eligible for PR, 199 were referred, and 178 were recorded as having declined.

Only 35% had COPD management plans, only 25% had asthma action plans and in the surgeries audited there was no record of bronchiectasis plans issued or management with appropriate course duration of antibiotics. Few clinicians were using the MK Respiratory template, preferring to use a limited QOF template to enter basic information, and although inhaler technique appeared to be checked on reviewing patients, the treatment delivered was frequently incorrect due to misdiagnosis.

During acute exacerbations prednisolone was prescribed routinely at a dose of 40mg/day instead of 30mg/day for COPD in some patients with no obvious asthma background whereas those with asthma or asthma/COPD overlap were managed on the lower 30mg/day.

This highlights the importance of staff having the right level of knowledge and skills to deliver respiratory care, as described in the Primary Care Respiratoy Society UK ‘Fit to Care’ document.15

Registers

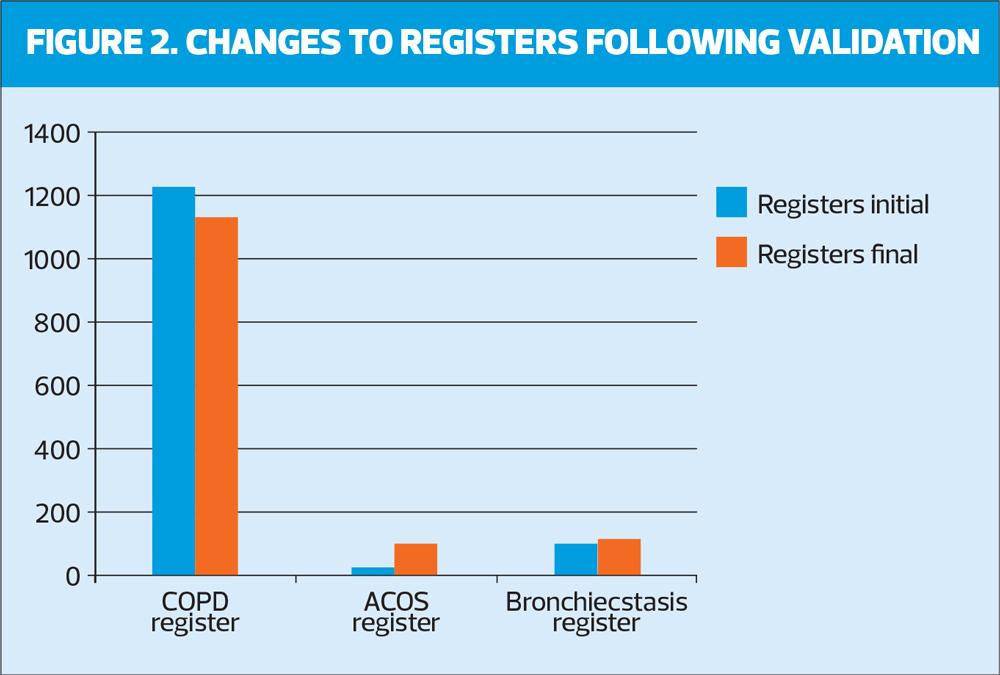

Following the audit the asthma and bronchiectasis registers increased and COPD register decreased by 5.6%. It was found that most patients with confirmed COPD had moderate airflow obstruction and most patients had an mMRC dyspnoea score recorded of 2 or 3. Those on dual asthma and COPD registers were reviewed and recoded as ACOS where indicated (see Figures 1 and 2).

Cost savings

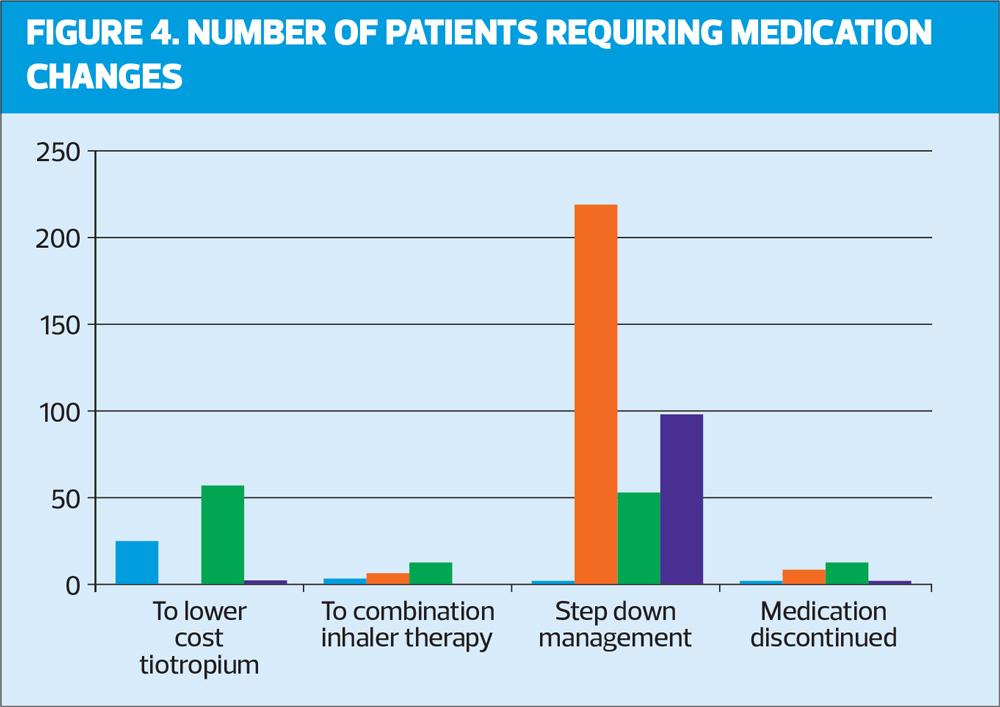

Once registers were cleansed, total potential savings of £117,270.43 were identified for all nine practices using appropriate prescribing (stopping triple therapy, switching to LABA/LAMA therapy, stepping down or switching to a lower cost medication, Figure 4) and using local prescribing guideline management.

CONCLUSIONS

The authors believe this is the first study of its kind, offering real time qualitative diagnostic data based on current COPD and asthma registers. Although time-consuming, this study allowed a unique insight into the diagnostic process for a cohort of patients held on COPD registers in nine Milton Keynes Practices. As a result of the authors’ earlier research, it is known that previous data capture using audit tools overestimated COPD prevalence and underestimated both asthma and bronchiectasis prevalence, while also missing crucial differential diagnoses.

Data extracted for epidemiological purposes relies on the knowledge, skills and training of the clinician responsible for the assessment, spirometric testing, its interpretation and prescribing of appropriate treatment trials. Data tools cannot interpret data quality or accuracy and more direct approaches are needed prior to assuming safety of the results.

Over the past decade, despite numerous COPD training events, the change of focus from delivering asthma training in favour of finding the ‘missing millions’ appeared to increase the prevalence of COPD without improving the diagnostic process, management, prescribing or referral for necessary interventions or investigations. Inhaler technique training, though demonstrably important, is costly to patients and the NHS alike when the inhaled medication is prescribed for the wrong diagnosis.

When optimising medication for long term conditions, treatment is titrated in response to ongoing monitoring. The authors did not find this to be the case with obstructive lung disease in this study and little challenge to existing COPD diagnoses occurred where there was no evidence of, or large changes to, subjective and objective testing.

Anecdotally there was also a paucity of history taking and historical peak flow measurements necessary to establish variable airflow obstruction and symptoms, suggesting a differential diagnosis of asthma.

Accuracy of respiratory diagnosis and assessment for important comorbidities, such as reflux, need to be ensured before review of pharmacological management. Correct diagnosis then allows significant potential cost savings by optimising pharmacological management, improving quality of care and life, reducing exacerbations and admission rates.

In order to deliver this effectively, staff must be appropriately trained.15 Regular training updates with succession planning when staff responsible for respiratory care leave practice helps build confidence to challenge historical diagnoses and employ current national guidance to manage symptoms.

Limitations of this study included time constraints to complete research across all 27 Milton Keynes Practices and potential cost savings related to appropriate prescribing for differential diagnoses and associated reduction of morbidity and mortality. However findings from this audit offered further evidence to commission a community based Assessment and Investigations of Respiratory Symptoms (AIRS) Clinic in Milton Keynes to overcome many of the issues raised.

REFERENCES

1. British Lung Foundation. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) statistics; 2022. https://statistics.blf.org.uk/copd

2. NICE NG115. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: diagnosis and management; 2018 (Updated 2019). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng115

3. Baverstock M, Woodall N, Maarman V. Do healthcare professionals have sufficient knowledge of inhaler techniques in order to educate their patients effectively in their use? Thorax 2010;65:A117-A118

4. NHS England. Right Care Focus packs for CVD, Neurological, Respiratory; 2016. https://www.england.nhs.uk/rightcare/products/ccg-data-packs/focus-packs/focus-packs-for-cvd-neurological-respiratory-maternity-april-2016/

5. Sin D, Miravitlles M, Mannino DM, et al. What is asthma-COPD overlap syndrome? Towards a consensus definition from a round table discussion. Eur Respir Journal 2016;48: 664–673

6. British Thoracic Society/SIGN. British guideline on the management of asthma; 2019 https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/guidelines/asthma/

7. Primary Care Commissioning. A Guide to Performing Quality Assured Diagnostic Spirometry; 2013 https://www.clinicalscience.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/artp-spirometry.pdf accessed June 2020

8. Fisk M, McMillan V, Brown J, et al. Inaccurate diagnosis of COPD: the Welsh National COPD Audit. Br J Gen Pract 2019;69(678):e1-e7 https://bjgp.org/content/69/678/e1

9. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). 2022 Global Strategy for prevention, diagnosis and management of COPD. GOLD 2022 reports. https://goldcopd.org/2022-gold-reports-2/

10. Gruffydd-Jones K, Keeley D, Knowles V, et al. Primary care implications of the British Thoracic Society Guidelines for bronchiectasis in adults. npj Prim Care Respir Med 2019;29:24. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41533-019-0136-8

11. Creamer AW, Barratt SL. Prognostic factors in hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Eur Respir Rev 2020;29:190167; DOI: 10.1183/16000617.0167-2019

12. Huang C, Liu Y, Shi G. A systematic review with meta-analysis of gastroesophageal reflux disease and exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. BMC Pulm Med 2020;20:2 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-019-1027-z

13. International Society for the Study of Cough. Hull Airway Reflux Questionnaire. https://www.issc.info/HullCoughHypersensitivityQuestionnaire.html

14. Nissen F, Morales D, Mullerova H, et al. Concomitant diagnosis of asthma and COPD: a quantitative study in UK primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2018;68(676):e775-e782

15. Lawlor R. Fit to care: key knowledge skills and training for clinicians providing respiratory care; 2017. https://www.pcrs-uk.org/sites/pcrs-uk.org/files/resources/2019-FitToCare.pdf

Related articles

View all Articles