The NICE draft guideline on COPD: Turning the tide?

BEVERLEY BOSTOCK-COX,

BEVERLEY BOSTOCK-COX,

RGN MSc MA QN

Nurse Practitioner Mann Cottage Surgery, Moreton in Marsh.

Education Lead, Education for Health, Warwick

NICE’s draft guidelines on COPD look set to buck the recent trend for controversy with an update that at first reading appears structured, sensible and scientific. We consider some of the proposed changes and the impact they may have on practice

This summer, NICE released its draft update on the diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) for consultation.1 This update was well overdue as the last review (an update of the 2004 guideline) was in 2010. Meanwhile the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) group continued to produce annual revisions of its guidance, arguably reflecting current evidence and best practice.2 NICE has been having a hard time over the past few years. With its strong focus on the financial aspects of guidelines it has come in for criticism that it is out of touch and lacks both pragmatism and a patient focused approach to clinical care. However, these new guidelines might be about to restore some of the credibility NICE badly needs as they offer an approach to COPD care which appears to be structured, sensible and scientific. To say there won’t be any controversy, however, would be naïve and unrealistic!In this article, we consider some of the changes recommended by NICE regarding the diagnosis and management of COPD and reflect on the impact these guidelines might have on practice, if they are adopted as they stand. Readers should be aware that the guidance has not yet been formally adopted and is still in the draft stage while feedback is being collated from registered stakeholders.The new guideline, once formally accepted and adopted, will update and replace NICE guideline CG101.3 The main areas affecting primary care which have been reviewed and, where appropriate, updated, include confirming the diagnosis, education and self-management, the use of inhaled therapies, mental health issues, the role of prophylactic antibiotics in frequent exacerbators and oxygen therapy.

DIAGNOSIS

The recommendations on the diagnosis of COPD have remained largely the same, in that NICE advises that cough and breathlessness, particularly in people with a significant smoking history, should be recognised as possible symptoms of COPD and should be investigated. Spirometry is still considered to be the gold standard investigation with post-bronchodilator spirometry being used to confirm the diagnosis. As with GOLD, a reduced post-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio is considered to indicate irreversible airflow obstruction with the FEV1 demonstrating the degree of airflow obstruction, rather than the severity of COPD. However, NICE recognises that there are differences of opinion about the cut off point for this ratio. NICE has previously suggested used a fixed ratio of 0.7 (70%),3 whereas the British Thoracic Society/Sottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (BTS/SIGN) asthma guidelines state that the lower limit of normal (LLN) value should be used.4 GOLD guidelines advise against the use of the LLN, saying that there is more evidence for using 70% as the normal value cut off point irrespective of the age of the patient.2 Just to add more into the melting pot of spirometry conundrums, the draft NICE guideline says clinicians should still consider a diagnosis of COPD in younger people if they have symptoms, even if the FEV1/FVC ratio is normal.1

So what are the implications for practice? As always, the common thread in diagnostics is to listen to the patient’s story, take a full history and use tests to back up a suspected diagnosis, not to make the diagnosis.5 As NICE and GOLD both remind us, symptoms plus risk factors indicate the need for spirometry but these are pieces of a jigsaw and the clinician then needs to look at the whole picture before making a diagnosis and considering a treatment plan with the patient.

To underline that fact, the draft NICE guideline reminds clinicians of the importance of differential diagnosis. The symptoms of COPD are fairly non-specific and many other lung conditions (and non-pulmonary diseases) can have the same or a similar presentation. Other investigations should therefore be considered, based on each individual presentation. These might include home peak flow readings in suspected asthma, an ECG and or echocardiogram if heart disease is suspected, a CT scan of the thorax to exclude other diseases, blood tests such as natriuretic peptides for heart failure, alpha 1 antitrypsin deficiency and/or a full blood count to measure haemoglobin and eosinophils, sputum examination for evidence of infection or referral for measurement of transfer factor for carbon monoxide (TLCO). It is also important to remember that conditions may co-exist and that people with COPD are at high risk of co-morbid conditions, often related to a significant smoking history. NICE 2018 (draft) also recommends that asymptomatic individuals found to have emphysema or ‘features of COPD’ on a chest X-ray or scan and who do not already have a diagnosis of COPD should have a review in primary care to include spirometry in order to ascertain whether they do in fact have COPD. If the diagnosis is not subsequently confirmed they should be aware that they are high risk for COPD and should be encouraged to return for review if symptoms occur. People with emphysema seen on a scan are also at increased risk of lung cancer,6 and may have a poorer prognosis if lung cancer is diagnosed.7

EDUCATION

The draft NICE guideline recommends that people who have been diagnosed with COPD (and their families or carers if appropriate) are given information about their condition.1 This is in line with the recommendations from the British Lung Foundation (BLF) who offer booklets and self-management plans to help people with COPD to understand more about their diagnosis and what they can do. These are available from www.blf.org.uk. NICE underlines that fact that any discussions patients and others have about the condition should be with HCPs who are experienced in managing COPD.

However, it could be argued that experienced HCPs may still be at risk of doing what they have always done, so teams in both primary and secondary care should ensure that they keep up to date with new developments and implement evidence based change into their practice. HCPs should be able to explain what the diagnosis means, what the symptoms are and why they occur, how to quit smoking and avoid exposure to passive smoke, where appropriate, and how to manage symptoms of stable COPD and during acute exacerbations. All patients should be advised of the benefits of physical activity and the role of pulmonary rehabilitation and local, national and online support in optimising wellbeing. People with COPD and their families should also be aware of the importance of using inhalers correctly, accessing vaccinations to reduce the risk of exacerbations and recognising and managing exacerbations if they occur. NICE reiterates the potential risk factors for acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) with the addition of a new risk factor – seasonal variation (winter and spring).

The NICE 2018 draft also advises HCPs to identify people who may be at risk of hospitalisation, and explain to them and their family or carers (where appropriate) what to expect if this happens.1 This might include discussion of procedures such as non-invasive ventilation (NIV), which is specifically mentioned in the draft. Again, HCPs should consider how much they understand themselves and reflect on how to increase their knowledge and understanding of interventions such as NIV in order to meet the NICE guideline recommendations.

INHALED THERAPIES

NICE has reconsidered its current approach to the use of inhaled therapies, including bronchodilators and combination therapies (inhaled corticosteroids with long acting beta2 agonists). The 2010 guidance recommended that treatment choices were based, to an extent, on FEV1. However, as GOLD has indicated, there is limited correlation between FEV1 (severity of airflow limitation) and severity of COPD.8 Severity of COPD is better defined using symptoms and exacerbation risk and this is what the GOLD ABCD algorithm is based on.

Previously NICE recommended inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) with long acting beta 2 agonists (LABA) in a combination inhaler for people with exacerbations and/or breathlessness, meaning that in theory almost anyone with COPD could ‘qualify’ for an ICS/LABA. However, GOLD has taken a different approach in recent years, based on the evidence of the potential benefit of long acting bronchodilators for all categories of COPD and in recognition of there being evidence of harm from ICS-containing inhalers, particularly when high dose combinations are used.

NICE’s advice on inhaled therapies in the draft guideline is startlingly simple: if a short acting bronchodilator is not adequately controlling symptoms, and/or patients are having exacerbations of COPD, they should step up to a dual bronchodilator. NICE specifically says in its draft guideline that there is no need to try patients on a single long-acting bronchodilator first.

NICE is clear, though, that all patients should receive standard treatment for COPD before stepping up and that standard treatment should include interventions for tobacco dependence, optimising non-pharmacological interventions, ensuring vaccinations are up to date and checking that short acting bronchodilators are already being used.

The NICE draft update states that ICS/LABA therapies should be reserved for patients who have COPD and asthma, with all standard treatment options as described above also being implemented.

Triple therapy should be saved for people with COPD with asthma who remain symptomatic or have exacerbations of COPD on an ICS/LABA.

NICE recommends that healthcare professionals (HCPs) should be aware of the risks of ICS inhalers and should be prepared to discuss these with patients. It may be, then, that if these guidelines are adopted, audits of currently diagnosed patients should be carried out to identify those on single long-acting bronchodilators (LABAs or long-acting muscarinic antagonists [LAMAs]) or those on ICS/LABAs where there is no evidence of asthma from the history or spirometry, and reviews should be carried out to explain why treatments are being changed. However, it remains doubtful whether people whose COPD is well managed using a LABA or LAMA alone warrant the same degree of attention as those on ICS/LABAs, especially if the latter are on high doses. Practice pharmacists could be invaluable in carrying out these audits and reviews if the draft is accepted and adopted as fully authorised NICE guidance. Before any changes are made, however, NICE reminds clinicians of the importance of keeping inhaled therapy regimes simple using the minimum number and type of inhaler device and ensuring that people receive inhalers they have been trained to use. This means that HCPs should be able to teach the correct technique and that, in line with the advice in the BTS/SIGN asthma guidelines, inhalers are prescribed by brand and inhaler device on prescriptions.

There are many clinical experts who will state that there is evidence for inhaled corticosteroids in COPD and that withdrawal of ICS/LABA inhalers risks causing exacerbations. It is important, then, to consider each individual case on its merits and to be mindful of the history that led that individual to be on an ICS/LABA before making any changes. A history of asthma and/or reversibility means that an ICS is required, but low doses may be adequate. The main role of ICS containing inhalers in COPD is in preventing exacerbations. Careful history taking and review of the medical records should minimise the risks of inappropriate ICS withdrawal. Vigilant comparison of the GOLD ABCD algorithm and the draft NICE inhaled therapies algorithm will clearly demonstrate that they have more similarities than differences.

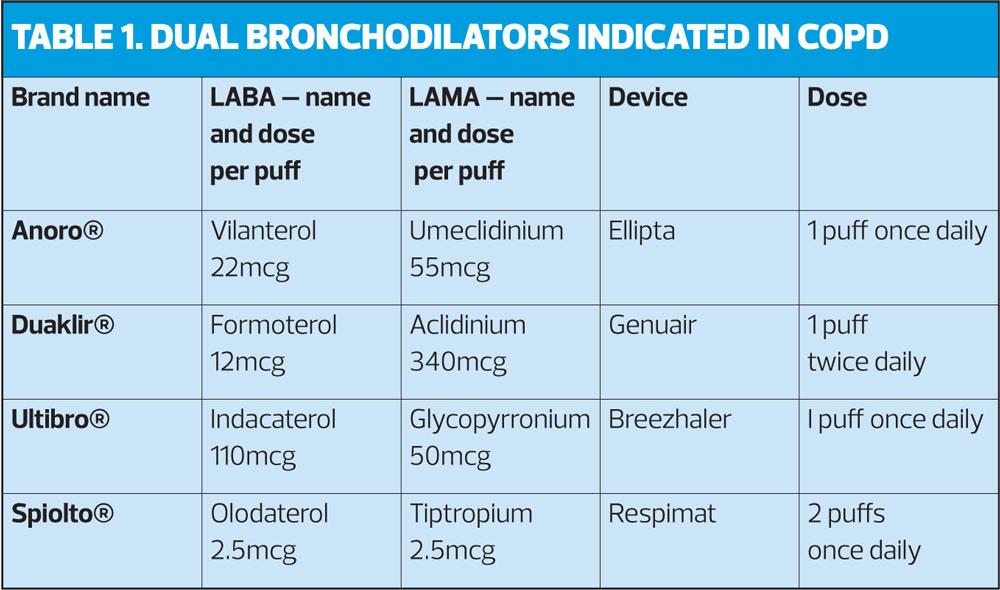

DUAL BRONCHODILATORS – A REMINDER

There are four dual bronchodilators currently on the market. (Table 1) The decision as to which to prescribe should be based on the patient’s ability to prime and inhale the device correctly. They may also have a preference for once daily or twice daily treatments. As mentioned above, consideration should be given, where possible, to minimising the number and type of device used.

COPD AND MENTAL HEALTH

In the 2018 draft guideline, NICE focuses on the impact of COPD on people’s mental health, highlighting the risk of anxiety and depression. HCPs should be alert to evidence of anxiety and depression in people with COPD particularly if they have severe breathlessness, are hypoxic or have been seen at or admitted to hospital with an exacerbation of COPD. NICE specifically recommends that HCPs should ask people with COPD if they experience breathlessness which they find frightening and that if they do, the HCP should consider whether cognitive behavioural interventions might be added to the self-management plan to help them manage anxiety and cope with breathlessness. On that basis, nurses should think about their knowledge on this subject (for example how to assess patients for anxiety and depression) and the advice that they are able to give. Along with online resources and books, other psychological and relaxation therapies have been shown to be useful in people with long term conditions such as COPD.9

SELF-MANAGEMENT

All people with long-term conditions should be supported and encouraged to self-manage. NICE states that this can be facilitated through the use of an individualised self-management plan developed in collaboration with the individual (and their family members or carers, if appropriate). The education points mentioned above should be reiterated, and the plan should be the subject of ongoing review at future appointments. For people at risk of AECOPD, an individualised exacerbation action plan should be developed. Oral corticosteroids and antibiotics should be supplied for the patient to keep at home as part of their exacerbation action plan but it must be ensured that they understand why these have been prescribed and how they should be used in the event of an AECOPD. This means that they are aware of not just the potential benefits but also the possible harm that may result from taking these drugs, especially if they are not used appropriately. NICE underlines the importance of ensuring that people with so-called rescue packs know to tell their healthcare professional when they have used the medication, to ensure that they are then issued with replacements. However, many clinicians would prefer to know as soon as possible after a patient has started the treatment so that they can follow up on their progress and intervene if the patient does not respond as expected. This reflects the fact that COPD exacerbations can mimic acute heart failure, pneumonia and other conditions.

In recognition of the fact that AECOPD can be an important prognostic indicator, HCPs should carry out further assessment of people who have used 3 or more courses of oral corticosteroids and/or oral antibiotics in the last year and consider whether a change of medication and/or referral for further assessment and investigations is indicated.

Specific advice given by NICE on managing AECOPD is in line with GOLD and is as follows: people with symptoms of AECOPD should adjust their short-acting bronchodilator therapy to treat their symptoms and take a short course of oral corticosteroids if their increased breathlessness interferes with activities of daily living and take antibiotics if their sputum changes colour or increases in volume or thickness beyond their normal day to day variation.

In the draft COPD guideline, NICE points out that its antimicrobial prescribing guideline for AECOPD is also in development and is expected to be published in December this year.

PROPHYLACTIC ANTIBIOTICS

In previous NICE guidance on COPD, prophylactic antibiotics were not recommended due to a lack of evidence. The NICE 2018 draft points out that there are still no long-term studies in people taking prophylactic antibiotics. GOLD does recommend their use in certain cases, and the NICE draft guideline reflects that position by saying that azithromycin, normally at a dose of 250mg 3 times a week, can be given to people with COPD with:

- 4 or more exacerbations per year or

- Significant daily sputum production or

- Prolonged exacerbations or

- Exacerbations requiring admission

This advice is given with the following provisos:

- They do not smoke

- They have optimised non pharmacological management and inhaled therapies

- Have had relevant vaccinations

- Have been referred for pulmonary rehabilitation if appropriate

If azithromycin is contraindicated, doxycycline 100mg daily can be given instead.

NICE warns that azithromycin has potential side effects so before starting on this regime, HCPs should ensure that the person has had an ECG to rule out prolonged QT interval and bloods to assess baseline liver function tests. There is also a small risk of hearing loss and tinnitus, so patients should be warned about this and asked to contact their nurse or GP if either of these symptoms occur. In the event of an AECOPD despite the use of prophylactic antibiotics, NICE 2018 recommends providing a non-macrolide antibiotic for the rescue pack.

The use of prophylactic antibiotics should be reviewed after 3 months and then 6 monthly to ensure that the risk: benefit profile of the treatment remains favourable. The NICE 2018 draft states that consideration should also be given as to whether respiratory specialist input is needed.

OXYGEN THERAPY

The recommendations for long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT) remain much the same with 15 hours minimum of LTOT being advised for people who do not smoke and who have a PaO2 below 7.3kPa when stable or a PaO2 above 7.3 and below 8kPa when stable if they also have secondary polycythaemia, peripheral oedema or pulmonary hypertension – a new addition for 2018. The updated draft advises that LTOT should not be offered to people who continue to smoke and while this may appear ethically controversial, it is, in fact, in line with evidence that suggests that the benefits of LTOT in smokers do not outweigh the risks.10 NICE also updates its advice on ambulatory oxygen, saying it should not be used for symptom management in people who have no or only mild hypoxaemia at rest, reserving it instead for people with exercise desaturation whose exercise capacity improves with oxygen.1

SUMMARY

The NICE draft guidelines for COPD offer an updated view of how COPD should be diagnosed and managed. While much of the guidance is in line with current GOLD guidelines there are some differences in their approach to the use of inhaled therapies. If the draft NICE guidelines are adopted, it might be useful to organise a practice meeting to discuss possible changes to future diagnosis and management procedures, update protocols and review existing cases. The final version of the guidance should be published by the end of 2018 and Practice Nurse will publish a full overview of and commentary on this guidance once it has been ratified.

REFERENCES

1. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Guideline. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: diagnosis and management. Draft for consultation, July 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/gid-ng10026/documents/short-version-of-draft-guideline

2. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management and prevention of COPD guidelines: 2018, 2017. http://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/GOLD-2018-v6.0-FINALrevised-20-Nov_WMS.pdf

3. NICE CG101. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: diagnosis and management. 2010. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg101

4. British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. British guideline on the management of asthma, 2016. https://www.brit-thoracic. org.uk/document-library/clinical-information/asthma/btssign-asthma-guideline-2016/

5. Bickley LS. Bates Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking. Philadelphia; Wolters Kluwer: 2017

6. Li Y, Swensen SJ, Karabekmez LG, et al. Effect of Emphysema on Lung Cancer Risk in Smokers: A Computed Tomography-based Assessment. Cancer Prevent Res (Philadelphia, Pa.), 2011;4(1), 43–50. http://doi.org/10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0151

7. Lee HY, Kim EY, Kim YS, et al. Prognostic significance of CT-determined emphysema in patients with small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis 2018;10(2):874–881. http://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2018.01.97

8. Westwood M, Bourbeau J, Jones PW, et al. Relationship between FEV1 change and patient-reported outcomes in randomised trials of inhaled bronchodilators for stable COPD: a systematic review. Respir Res 2011; 12(1):40. https://doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-12-40

9. Yohannes AM, Junkes-Cunha M, Smith J, Vestbo J. Management of Dyspnea and Anxiety in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Critical Review. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2017;118(12):1096.e1-1096.e17. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.09.007. Epub 2017 Nov 3.

10. Calverley PM, Legget RJ, McElderry L, Flenley DC. Cigarette smoking and secondary polycythemia in hypoxemic cor pulmonale. Am Rev Respir Dis 1982;125:507–10.