GOLD guidelines 2021 – what do you need to know?

Beverley Bostock-Cox

Beverley Bostock-Cox

RGN MSc MA QN

Nurse Practitioner Mann Cottage Surgery, Moreton in Marsh

Education Facilitator Devon Training Hub

PCRS Policy Forum Member

Practice Nurse 2021;51(1):13-16

Given that the NICE guideline on the diagnosis and management of COPD is now two years old – and evidence is constantly evolving – it is important that general practice nurses are aware of the more regularly updated guidance from GOLD and how it may impact on practice

At the end of every year, the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) publishes its latest update on the diagnosis and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) for the year to come. As we reported in the December issue of Practice Nurse, the 2020 update for 2021 had some extra concerns to address, in light of the global pandemic.1

In this article we highlight the key areas addressed by GOLD and consider how these guidelines could impact on how general practice nurses (GPNs) approach the challenges of diagnosing and managing this important condition. We also compare the international GOLD guidelines with the advice included in National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance,2 and review NICE’s rapid review of managing COPD in the time of COVID-19.

By the end of this article readers should be able to

- Recognise the key points from the new GOLD guidelines relating to primary care

- Compare GOLD recommendations with those from NICE

- Evaluate the overall approach to the diagnosis and management of COPD during a pandemic

- Establish a guideline-backed approach to managing COPD in people who have COVID-19

- Consider the role of remote consultations for people with COPD

KEY POINTS FROM THE GOLD 2021 REPORT

DIAGNOSIS

Reassuringly, there are many areas in the new GOLD guidelines which remain the same as previous iterations. The focus is, as always, on careful diagnosis and the appropriate management of stable COPD and acute exacerbations. With respect to the diagnosis, GOLD reminds us that this depends upon the presence of typical symptoms, such as cough, breathlessness, sputum production and reduced ability to carry out normal activities of daily living, in people with risk factors for COPD. In the western world, the number one risk factor is a history of smoking, with a pack year history of 20-plus considered to confer the greatest risk.

Once the presence of symptoms and risk factors has been established, it is then important to confirm the presence of irreversible airflow obstruction, a central feature of COPD. In normal times this would be achieved through post-bronchodilator spirometry. A forced expiratory volume in one second to forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) ratio of 70% (0.7) or less would indicate an obstructive pattern and the degree of reduction of the FEV1 would define the severity of the airflow obstruction, which would help to predict prognosis.1 However, as a result of the pandemic, primary care has largely stopped performing spirometry. The Primary Care Respiratory Society (PCRS) recently published a position statement on performing spirometry during the pandemic.4 The advice is that during the COVID pandemic, spirometry should only be carried out in primary care when the results will definitively inform or change patient management.

For perhaps the first time, peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) meters have been recommended as a way of assessing lung function in people suspected of having COPD, with PCRS advising that if readings are consistently below 75% of predicted and have no evidence of variability (i.e. none of the morning dips which might be expected in asthma, for example) then this can be considered to be in line with a possible diagnosis of COPD until full spirometry can be carried out safely.4

Asthma UK has also published advice on restarting respiratory services in the pandemic.5 Its advice, based on guidance from the Association of Respiratory Technicians and Physiologists, is that lung function tests can be safely carried out in community diagnostic hubs. However, if these are not established, plans should be put in place to carry out tests appropriately in GP practices, hospitals or other designated spaces. It is worth noting that this statement was published in August when COVID cases appeared to be falling. The current situation with a new variant of highly transmissible coronavirus infection is very different.

In a previous article on remote respiratory consultations during the pandemic, the potential for home spirometers such as the Spirobank Smart to offer a new way to test respiratory function at this time was highlighted as a possible option.6

GOLD’s position on spirometry is that while there is a high prevalence of COVID-19, spirometry should only be used when essential for COPD diagnosis and/or to assess lung function status for interventional procedures or surgery.

Overall, then, it seems that each organisation (surgery, Primary Care Network, hospital or hub) will need to make their own decisions about how and when to test people in order to confirm the diagnosis of COPD.

MANAGEMENT

Once the diagnosis has been made, the management of COPD remains much as it was in the 2020 GOLD guidelines. The focus is on assessing symptoms (using the modified MRC dyspnoea scale and/or the COPD Assessment Test) and exacerbation history in order to offer the most appropriate medication along with smoking cessation and the management of any co-morbidities.1 GOLD also recommends considering whether any environmental factors are impacting on symptoms and exacerbation risk. People with COPD should also be offered lifestyle advice, including support to remain physically active. Pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) programmes offer these elements and more, so people with COPD should be assessed as to their suitability for PR and referred as and when the resource is available. In the pandemic, many areas have been able to convert their face to face PR programmes into virtual, online courses. Although not everyone will be able or willing to join online, this has at least offered an option to those who are.

Good inhaler technique is essential if medication is to be effective in reducing symptoms and the risk of future exacerbations. There are several routes which allow clinicians to teach correct inhaler technique when not in a face to face situation, not least the Asthma UK website, which also includes videos on inhalers designed for people with COPD.7

GOLD also highlights the importance of education to support self-management, including the provision of written action plans focused on risk factor management. The British Lung Foundation (BLF) has some examples of self-management plans on its website at https://www.blf.org.uk/.

GOLD recommends assessing people at each review as to whether they might need more intensive input, for example through referral to other services providing interventions such as non-invasive ventilation (NIV), long-term oxygen therapy (LTOT), lung volume reduction surgery (LVRS) or palliative care.1 The role of the GPN in primary care is to be aware of people who are likely to benefit from any of these treatments and who should therefore be referred. People with recurrent severe exacerbations may benefit from NIV, those who are chronically hypoxic may require LTOT, people with bullous emphysema may improve symptomatically and in terms of mortality risk after LVRS and people with recurrent admissions on maximal tolerated therapy and with an FEV1 of less than half of their predicted value should be offered discussions about palliative and end of life care.1,2,8-10

Interestingly, GOLD also recommends a minimum of annual spirometry, whereas the PCRS previously welcomed the decision to remove repeated lung function testing from the annual Quality Outcomes Framework review.11 The rationale for removing the FEV1 from the annual review was the poor correlation between lung function, symptoms and outcomes.12 Although an accelerated reduction in FEV1 is associated with a poor prognosis, there are many other features linked to symptoms and exacerbations that will indicate when an individual with COPD is becoming more unwell with a poor prognosis. When time is limited, as it is for all of us working in general practice, it seems appropriate to use what time we have available for each interaction wisely, and time is rarely better spent than simply listening to someone telling their story. We are frequently reminded of Ostler’s words: ‘Listen to the patient. He is telling you the diagnosis’.

INHALED THERAPIES

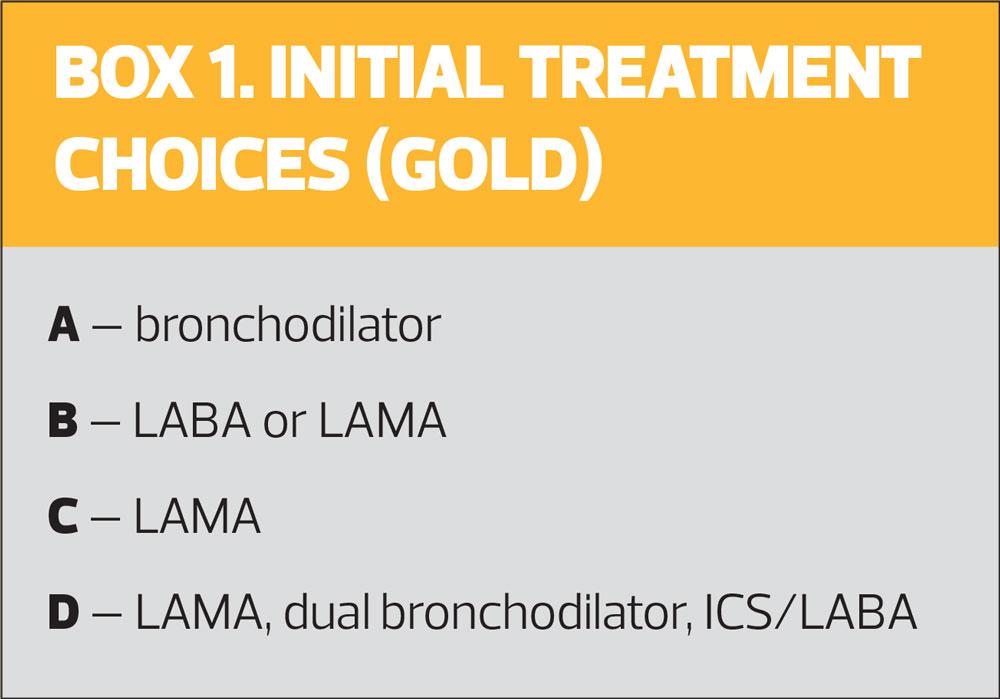

Having introduced and updated the ‘ABCD’ algorithm over the past few years, GOLD maintains the same approach this year (Figure 1, Box 1).

The focus is on bronchodilator therapies for COPD, as all people with symptomatic COPD will need these. GOLD prioritises long-acting bronchodilators over short-acting for most people, with short-acting bronchodilators being reserved for those who have only occasional symptoms and for those who have breakthrough symptoms despite being on a long-acting bronchodilator. Where NICE recommends stepping straight from a short-acting bronchodilator to dual long-acting bronchodilators, GOLD states that single or dual long-acting treatment may be offered depending on the symptoms and features of each individual’s COPD.1,2 Oral bronchodilators, including theophyllines, are not recommended by the authors of the GOLD guidelines.

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) in COPD have been the subject of debate over recent years, but both GOLD and NICE advise that their use should be targeted at those most likely to benefit. ICS therapy, like all medication, has risks as well as benefits, but for people with COPD, the use of inhaled corticosteroids needs careful consideration because of the specific respiratory risk of pneumonia, along with other risks, such as the risk of developing (or worsening) diabetes which has been reported in people on high dose ICS.13,14

GOLD offers strong support for the use of ICS therapy (with a long-acting beta2 agonist, as ICS monotherapy is not licensed in the United Kingdom) for people with a history of any hospitalisation for acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) and for people with a history of two or more moderate exacerbations, despite appropriate use of long-acting bronchodilators. GOLD also recommends ICS therapy for people with COPD and blood eosinophils of 300 cells/μL or more and for people with a history of asthma.

ICS therapy should also be considered in those with one moderate AECOPD with blood eosinophils of 100-300 cells/μL despite long-acting bronchodilator use.

GOLD also offers clear advice on when ICS-containing inhalers should be avoided – specifically if there is a history of repeated pneumonia infections, or where the blood eosinophils are less than 100 cells/μL, or where there is evidence of a mycobacterial infection. Importantly, though, both GOLD and PCRS advise against taking people with COPD off ICS-containing therapies during the pandemic.

GOLD recommends continuing with all current treatment and approaches in stable COPD at this time, including lifestyle interventions, but with special attention being paid to infection control procedures by both clinicians and patients alike. People with COPD should be advised to wear a face covering and to ensure that they have adequate supplies of medication.

MANAGEMENT OF ACUTE EXACERBATIONS

The GOLD guidelines, along with NICE, both include advice on the management of AECOPD, although their advice differs in terms of pharmacological management.1,2 The latest GOLD guidelines state that antibiotics and oral corticosteroids should be considered in severe exacerbations.1 In separate guidance, on COPD and COVID-19, GOLD states that systemic steroids and antibiotics should be used in AECOPD in line with the usual indications.15 They also offer advice on the use of oxygen saturations, blood gases, chest X-Rays, heparin, oxygen and NIV for severe AECOPD. NICE previously published an antimicrobial guideline on managing AECOPD, which recommends careful consideration of the use of antibiotics in exacerbations, with the observation that even severe exacerbations are not necessarily driven by bacterial infections.16 This begs the question as to what advice should be given about providing rescue packs. NICE and the PCRS, among others, have published advice on the management of AECOPD in the pandemic.3,6

NON-PHARMACOLOGICAL INTERVENTIONS

GOLD recommends offering advice on getting adequate sleep to people with COPD, who may get particularly breathless when lying flat (orthopnoea), especially if they have heart failure, which may occur more frequently in people with COPD than in those without.

Breathing exercises can be offered as well as advice on pacing activities to conserve energy and educe breathlessness. Stress and anxiety can also impact on breathlessness so mindfulness can help people to relax and manage their breathlessness non-pharmacologically as well as through medication.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS AND CO-MORBIDITIES

The primary risk factor for COPD is a significant smoking history and this will also put people at risk of other conditions. Furthermore, the classic symptoms of COPD such as cough, breathlessness and/or chronic sputum production may also be seen in other conditions which may be confused with or occur alongside COPD. These might include pneumonia or pleural effusion, where a chest X-ray would be needed to confirm the diagnosis; atrial fibrillation, where an electrocardiogram would be indicated; or heart failure, where an echocardiogram would be the gold standard diagnostic test. GOLD reminds healthcare professions to consider the differential diagnoses in a suspected exacerbation of COPD as well as when diagnosing and managing suspected COPD.

COVID-19 and COPD

Inevitably, GOLD has produced specific advice within the latest published guidelines on managing COVID-19 in people with COPD and vice versa.1 This addresses the challenge of differentiating between a COVID-19 infection and COPD, as the symptoms can overlap. Although there is no evidence that people with COPD are at increased risk of coronavirus infection, they will be at increased risk of a viral-induced acute exacerbation if they do get it. In people who have COPD and report worsening symptoms, testing for COVID-19 is advised. Moderate to severe infections should be treated with evolving pharmacological approaches, including the anti-viral drug remdesivir, the oral corticosteroid dexamethasone, and anticoagulation.1 COVID-19 is a prothrombotic condition and people with COPD may already be at increased risk of clotting.10,18 Particular attention should be paid to oxygen saturations as ‘silent hypoxia’ has been associated with increases in COVID-related morbidity and mortality.19

GOLD also stresses the importance of post-COVID follow up and rehabilitation.

REMOTE CONSULTATIONS DURING THE PANDEMIC

By now, most GPNs will have addressed the need for remote consultations and will have tailored their approach to fit. Whether carrying out telephone appointments or video consultations, either singly or in groups, the importance of balancing the risks and benefits of different methods of interacting with patients has been of paramount importance. It is essential that people with COPD and other long-term conditions get the advice and support that they need at this challenging time. GOLD discusses the challenges of remote consultations on its website and recognises that new methods of consulting are likely to be here to stay. There is a checklist on the GOLD website aimed at showing clinicians how to set up, carry out and close a remote consultation, including how to offer appropriate follow up.20 There is also clear recognition of the importance of offering face to face consultations where necessary.

Medicolegal considerations that should be addressed include the importance of thorough and accurate documentation and the need for privacy and confidentiality. It is also essential that arrangements for follow up are clear for both parties and that the advice given including safety-netting, is clearly recorded in the notes.

IN SUMMARY

The 2021 GOLD report not only offers advice on the diagnosis and management of COPD in general, but also includes COVID-specific recommendations around the use of spirometry, managing stable disease and treating COPD in COVID-positive patients. GPNs reviewing people with COPD this winter and beyond, need to be aware of the recommendations made in this update, along with national recommendations from organisations such as NICE and the PCRS. The evidence around COPD, COVID-19 and when the two conditions collide, is ever-evolving so taking a broad overview of these and other publications will support the implementation of best practice during these challenging times.

REFERENCES

1. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for Prevention, Diagnosis and Management of COPD. 2021 Report; 2020 https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/GOLD-REPORT-2021-v1.0-16Nov20_WMV.pdf

2. NICE NG115; Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: diagnosis and management; 2018 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng115

3. NICE NG168. COVID-19 rapid guideline: community-based care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); 2020. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng168

4. Primary Care Respiratory Society. PCRS Position Statement Spirometry and lung function testing in primary care during the Covid 19 Pandemic; 2020. https://www.pcrs-uk.org/sites/pcrs-uk.org/files/Position-Statment-Spirometry-20201123.pdf

5. Asthma UK. Recovery and reset for respiratory: restoring and improving basic care for patients with lung disease; 2020. https://www.asthma.org.uk/283059c7/globalassets/campaigns/publications/restarting-basic-care-final.pdf

6. Bostock B. Remote control: the respiratory annual review in lockdown and beyond. Practice Nurse 2020;50(6):16-20

7. Asthma UK. How to use your inhaler; 2020 https://www.asthma.org.uk/advice/inhaler-videos

8. Elliott MW. (2012) Non-invasive ventilation in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a new gold standard?. In: Pinsky MR, Brochard L, Mancebo J, Antonelli M. (eds) Applied Physiology in Intensive Care Medicine 2. 2012; Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-28233-1_35

9. Alderazi S, et al. Lung volume reduction surgery – an underutilised treatment? Eur Respiratory Journal 56 (suppl 64) 2020;DOI: 10.1183/13993003.congress-2020.3138

10. Bikov A, et al. FEV1 is a stronger mortality predictor than FVC in patients with moderate COPD and with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2020;15:1135-1142 https://doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S242809

11. Primary Care Respiratory Society. Respiratory QOF changes; 2019 https://www.pcrs-uk.org/news/respiratory-qof-changes-come-force-next-week

12. Oga T, et al. Longitudinal deteriorations in patient reported outcomes in patients with COPD. Respir Med 2007;101(1), 146–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2006.04.001

13. Agusti A, et al. Inhaled corticosteroids in COPD: friend or foe? Eur Respir J 2018;52:1801219; DOI: 10.1183/13993003.01219-2018

14. Suissa S, Kezouh A, Ernst P. Inhaled corticosteroids and the risks of diabetes onset and progression. Am J Med 2010;123(11):1001–6. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.06.019

15. Global Initiative for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease: The 2020 GOLD Science Committee Report on COVID-19 & COPD. Am J Resp Crit Care Med; published online 4 November 2020. https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/abs/10.1164/rccm.202009-3533SO

16. NICE NG114. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (acute exacerbation): antimicrobial prescribing; 2018 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng114

17. Primary Care Respiratory Society. PCRS Pragmatic Guidance for crisis management of asthma and COPD during the UK Covid-19 epidemic; 2020. https://www.pcrs-uk.org/resource/pcrs-pragmatic-guidance-crisis-management-asthma-and-copd-during-uk-covid-19%C2%A0epidemic

18. Du F, Liu B, Zhang S. COVID-19: the role of excessive cytokine release and potential ACE2 down-regulation in promoting hypercoagulable state associated with severe illness. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2020;1–17. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11239-020-02224-2

19. Teo J. Early Detection of Silent Hypoxia in Covid-19 Pneumonia Using Smartphone Pulse Oximetry. J Med Syst 2020;44(8):134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-020-01587-6

20. GOLD. Remote COPD patient follow-up during COVID-19 pandemic restrictions; 2020 https://goldcopd.org/remote-copd-patient-follow-up-during-covid-19-pandemic-restrictions/