Straight talking: making health literature equitable

Harriet Smith

Harriet Smith

Workstream Lead at Yorkshire & Humber Academic Health Science Network (AHSN)

Dr Llinos Jones

Respiratory consultant at The Mid Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust

Dr Michelle Bartholomew

School of Human and Health Sciences University of Huddersfield

Dr Mike Snowden

School of Human and Health Sciences University of Huddersfield

Practice Nurse 2023;53(3):11-14

Why do whole communities feel excluded and underrepresented in health literature on long term conditions? An Academic Health Science Network project aimed to find out – and to provide solutions

The NHS purportedly strives to make health and social care equitable, and paramount to this are principles of the Core20PLUS5 approach, which aims to reduce healthcare inequalities at both national and system level.1 However, despite this initiative, there is substantial evidence that people from different ethnic communities do not have access to the information they need to manage their long term health conditions in a format they can easily understand.2

The UK census in 2011 identified approximately 770,000 people living in England who said they spoke little or no English.3 Only two-thirds (65%) of people who could not speak English well or at all were in good health, compared with nearly 9 in 10 (88%) who could speak English very well or well. These figures increased by 2% in the 2021 census.4 This reduced proficiency in the use of English language presents a distinct challenge for disadvantaged groups to access appropriate health care and contributes to poorer health outcomes. Further evidence shows a measurable decline of age-related good health in people who are less proficient in English.5

Total NHS spending on translation and interpreting services for trusts and Health Boards in the UK was £62,409,493 in 2018-2019, and this increased to £65,962,418 in 2019-2020.6 These figures included Welsh and services for the deaf and blind, for example British Sign Language (BSL) and Braille. It is clear that correct and informative materials can contribute to improved health outcomes. Public Health England, in its ‘State of respiratory health in Yorkshire and the Humber’ report, asserted that ‘respiratory diseases are overwhelmingly associated with modifiable factors and behaviours. Respiratory illness does not affect population groups equally and is subject to strong social patterning’.7

It is well documented that asthma-related morbidity disproportionately affects more people from ethnic minority backgrounds. They have poorer continuity with healthcare providers, less familiarity with primary healthcare practitioners and are more likely to present to Accident and Emergency departments (AED) as a primary source of care.8

Despite this, asthma information in alternative languages is not readily available. Anecdotal evidence from clinicians, and those from minority ethnic groups, found that patients in Yorkshire were struggling to understand and manage their respiratory condition, or to know what treatments were available to them.

Drawing upon a classical approach to change,9 it became clear that a distinct and urgent change in asthma health care was needed. Indeed, providing information in a format which is understandable and culturally relevant is critical for successful health outcomes.

Securing funds from the Pathway Transformation Fund (PTF) and the Accelerated Access Collaborative Rapid Uptake Product Asthma Biologics project, enabled the development of a cross disciplinary project evaluating current educational literature available for ethnic minority groups and to develop a set of resources that were ‘fit for purpose’. The ‘Straight Talking: Making health literature equitable’ project concentrated on asthma and aimed to dispel some of the myths and stigma attached to this condition. The focus was people from the South Asian community, one of the communities with the highest rate of uncontrolled asthma. South Asian individuals living with asthma in the UK are more likely to experience excess morbidity and increased hospitalisation rates than any other ethnic group.8

The primary aim for this project was to improve patient engagement and education on asthma management and treatment options, providing support with adherence to their inhaled therapy and to minimise harm associated with excess corticosteroid use.

THE SOLUTION

The project team adopted an evaluation audit approach using the NHS Change Model guide.10 Data collection techniques involved a desktop review of existing resources and the collation of data from the use of focus group and individuals’ perceptions of existing resources, obtained from community members and health care professionals.

The team intended to undertake this project over a 12-month period, but with delays due to COVID-19, the reality was that the work took 18 months to complete.

Working with South Asian patient groups in Mid Yorkshire, the project team have been able to increase patients’ knowledge of asthma, and the need to engage with primary care services. By understanding their long term condition better, it aided self-management, thereby empowering patients to approach health professionals when their symptoms are uncontrolled.

The project also involved identifying and training some existing COVID-19 champions to become wider asthma community champions. These individuals are part of the local communities and understand the language and culture. Not only was this an excellent, innovative approach, but it also avoided excluding those who were not engaging with digital information. Information collated highlighted key issues regarding cultural differences and barriers:

- Barriers perceived to be linked to stereotype

- Misconceptions/denial about the condition

- Attitudes towards illness. For example, don’t bother the doctor, delay visit, use AED when in serious need of help

- Misconceptions around asthma and food (resolution and causation)

- Misconceptions around the causes and connotations of asthma

- Stigma of living with asthma (reluctance to seek help)

- Insufficient socio-cultural support

- Limited knowledge of health care systems and how to access them

Community members also stated that they often felt excluded and under-represented in the health literature that is available to them. Much health literature did not visibly represent them, nor did it cover the specific cultural questions that they wished to ask. This project clearly illustrates how it is possible to tackle health inequalities by harnessing the wisdom of local communities to co-produce targeted resources and interventions.

HOW THE RESOURCES WERE DEVELOPED

For the first part of the evaluation the project team were keen to understand the challenges faced by community members. These included not being able to understand what they had been told by healthcare professionals and the information that had been given to them because of language difficulties. They had a distinct lack of awareness of what asthma actually was and how it can affect them.

Community members had limited awareness of the support that was available to them. For example, they were not too sure when they needed to use their inhalers. They believed that they did not need to use their inhaler unless they were having breathing difficulties. They did not understand the differences between two different types of inhalers and did not want to use the inhalers during Ramadan.

The project team also showed the patients existing asthma literature, which was viewed as being largely negative. The images did not show individuals like them, they depicted predominantly white individuals, the language used was confusing with lots of medical terminology. Further, the leaflets were poorly presented both in font size and layout. The literature available did not meet their regional language differences and some could not access online resources.

The team decided to harness an ‘authentic voice’ and use the knowledge that exists in these communities using community champions based within the areas identified as hotspots. An authentic voice is defined by the project team as one that reflects the community, context and health condition. Community Champions were recruited and trained to form a bridge between community members and members of the project team, thus providing an advocate for those members who were reticent to express their views.

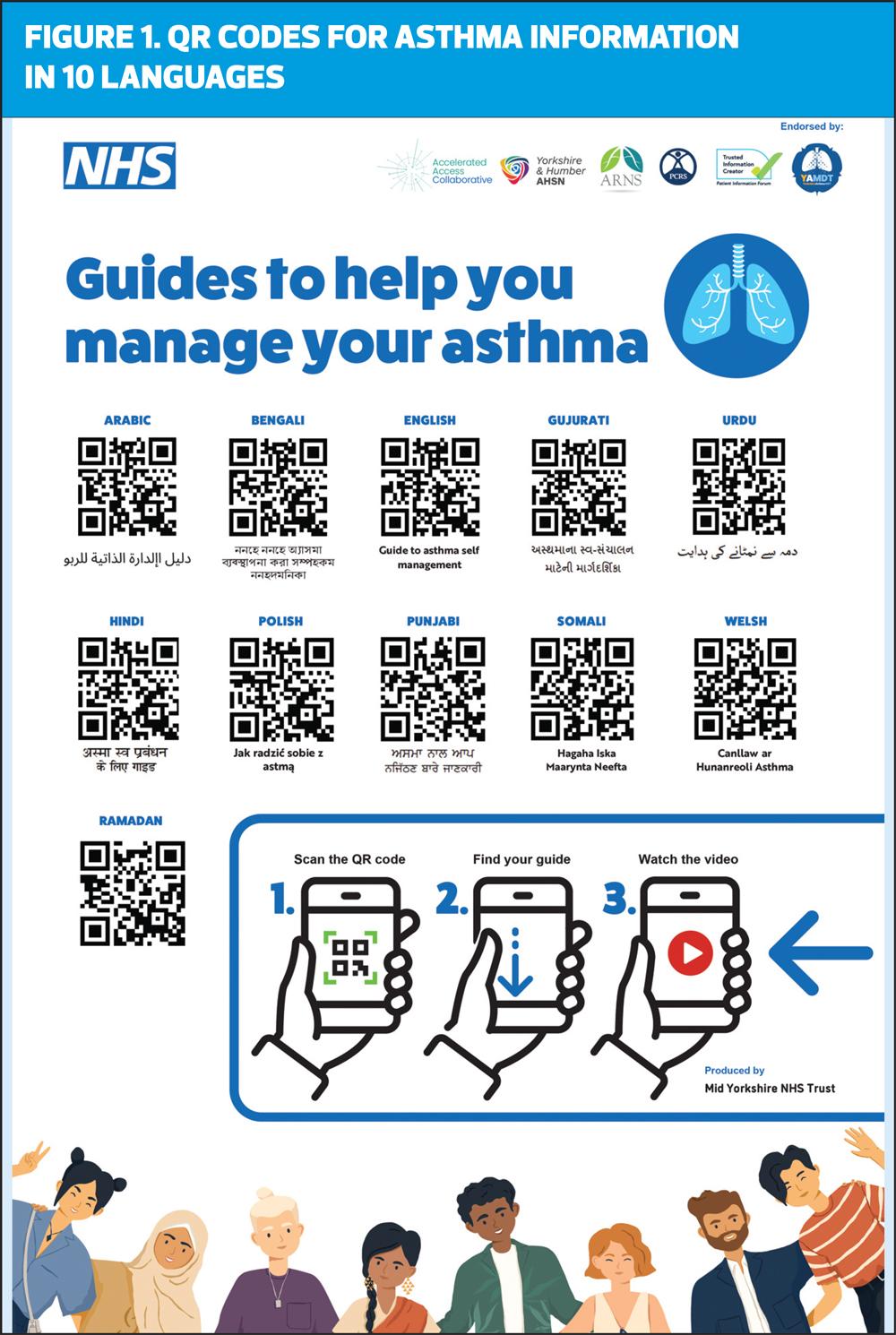

Some of the resources developed in collaboration and co-designed with patients and community groups included the development of graphic medicine sheets, animations, videos in 10 different languages to help self-manage asthma and how to take medication during Ramadan, leaflets and QR codes linked to web pages in different languages, as seen in Figure 1.

One of the resources that evaluated extremely well was the production of a computer-generated avatar that the project team nicknamed ‘Fatima’ (see Figure 2.). At first, they were not convinced that she would be relatable, however members of the community focus groups believed she was a real person from the local community. All translated materials had to be quality checked for accuracy, and to ensure that the information was given in a truly accessible format. It was therefore important to the team to get all material quality stamped with the PIF TICK, the UK’s independently-assessed quality mark for trusted health information.11

Data gathered from the interviews and focus groups indicated that taking medicines during Ramadan was problematic, and community members were given mixed messaging around whether oral medication could be used. This being the case, the project team worked very closely with the chaplains from The Mid Yorkshire Hospitals Trust, and local Muslim scholars to co-produce a video on asthma management and Ramadan.

The resources created include myth busting statements and simple, accessible messages, and include:

- What is asthma?

- What are asthma inhalers?

- Staying well with asthma

- Coming to Hospital

- Asthma Action Plans

- How to use your Peak Flow Meter

- Is your asthma under control (animation)?

- Asthma medication during Ramadan

Table 1 provides links to a video on Ramadan, the use of inhaled and oral medicines and the avatars, produced in 10 different languages.

CONCLUSION

What was apparent from this project is that much more needs to be done. The provision of understandable, accessible and culturally-relevant health education material is exceptionally important, not only in relation to helping people self-manage their condition, but also in preventing and reducing attendance at the AED and inpatient admissions later. All the resources produced during this project are accessible and are held on the British Thoracic Society Respiratory Futures website, for both clinicians and patients to access.11

REFERENCES

1. NHS England. Core20PLUS5 (adults) – an approach to reducing healthcare inequalities. https://www.england.nhs.uk/about/equality/equality-hub/national-healthcare-inequalities-improvement-programme/core20plus5/

2. Kapadia D, Zhang J, Salway S, et al. Ethnic Inequalities in Healthcare: A Rapid Evidence Review NHS Race and Health Observatory; 2022 https://www.nhsrho.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/RHO-Rapid-Review-Final-Report_v.7.pdf

3. Office for National Statistics. Census: Language in England and Wales: 2011 https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationand community/culturalidentity/language/articles/languageinenglandandwales/2013-03-04

4. Office for National Statistics. Census: Language, England and Wales: Census 2021 https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulation andcommunity/culturalidentity/language/bulletins/languageenglandandwales/census2021

5. UK Government. Building stronger communities through English language learning 2018 Census. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/building-stronger-communities-through-english-language-learning

6. InBox Translation. NHS spending on translation and interpreting services; 17 May 2022. https://inboxtranslation.com/resources/research/nhs-spending-translation-interpreting-services/

7. Public Health England. State of Respiratory Health in Yorkshire and the Humber;2019. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/826788/PHE_State_of_Region_Respiratory_YH_2019.pdf

8. Office for National Statistics. People who cannot speak English well are more likely to be in poor health; 9 July 2015. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/culturalidentity/language/articles/peoplewhocannotspeakenglishwellaremorelikelytobeinpoorhealth/2015-07-09

9. Lippitt R, Watson J, Westley B. The Dynamics of Planned Change. 1958; New York: Harcourt, Brace and World.

10. NHS England Sustainable Improvement. Change Model Guide Team https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/change-model-guide-v5.pdf

11. Respiratory Futures in Partnership with the British Thoracic Society https://www.respiratoryfutures.org.uk/whats-new/new-inhaler-technique-qr-code-poster/