Chronic kidney disease in the 21st century: going digital

Dr Matthew Graham-Brown

Dr Matthew Graham-Brown

Clinical Associate Professor of Renal Medicine, University of Leicester and Honorary Consultant Nephrologist, University Hospitals of Leicester;

NIHR Leicester Biomedical Research Centre, Leicester

Dr Courtney Lightfoot

Research Associate, Leicester Kidney Lifestyle Team, Department of Population Health Sciences, University of Leicester

Practice Nurse 2025;55(1):14-17

Most patients with CKD are looked after in primary care and will never meet hospital specialist teams: engaging them in programmes that promote effective self-management is crucial to improving outcomes and quality of life

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects around 10% of the population globally,1 and is associated with high levels of morbidity and mortality.2 It has been described as a public health emergency and, in the UK, is estimated to affect around 7 million people.3 While the risk of developing end-stage kidney disease (needing dialysis or a kidney transplant) is low, the risk of developing complications of CKD, particularly cardiovascular complications and early death, is high.3 Moreover, the cost of kidney disease to the UK health economy is enormous and is predicted to increase significantly over the next 10 years if steps are not taken to improve early identification and appropriate management.

CKD RISK STRATIFICATION – WHAT’S NEW?

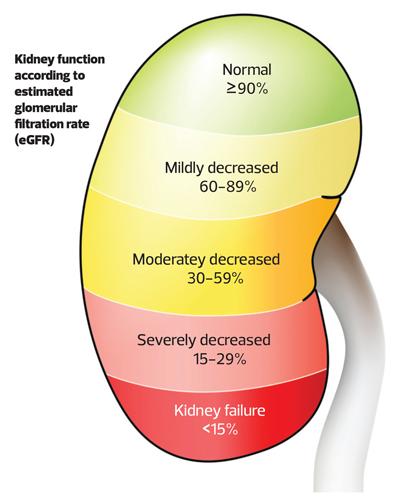

NICE defines CKD as ‘abnormalities in kidney function or structure (or both) present for more than three months with associated health implications’.4 The staging of CKD based on estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) will be familiar to most,4 with stages of CKD progressing from 1 to 5 as eGFR falls from >90ml/min/1.73m2 to <15ml/min/1.73m2. What is perhaps less well known is the importance of proteinuria in establishing stage of CKD (Figure 1). Proteinuria is also crucial to defining the risk posed to the patient of developing progressive CKD (that may lead to kidney failure),5 and the risks of death and adverse health outcomes, particularly cardiovascular disease.6 Not only is the degree of proteinuria an independent determinant of poor health outcomes but therapies that reduce proteinuria slow the progression of kidney disease, reduce mortality risk and risk of cardiovascular disease.7 Simply put, proteinuria is a brilliant marker of risk for patients with CKD. It is recommended that proteinuria be measured with a simple spot urine test for albumin creatinine ratio (uACR).4 Testing urine is simple, but it is not routinely done even in at-risk cohorts.8 If there is one thing you take from reading this article, let it be that all patients with CKD need kidney function tests and uACR testing every 6 months, and screening for at-risk groups (including patients with diabetes or patients on any cardiovascular drugs, including anti-hypertensive agents) should have screening for CKD with kidney function tests and uACR tests. Why is this so important? Well, because we can now risk stratify patients with CKD with the kidney failure risk equation (KFRE).9 By inputting a patient’s, age, sex, eGFR and uACR result into the KFRE calculator you can determine a patient's 2- and 5-year risk of developing kidney failure (https://kidneyfailurerisk.co.uk).10 Use of the calculator is now recommended by NICE for stratifying referrals to secondary care, with a 5% risk of kidney failure at 5 years being the threshold for referral.4

EVIDENCE-BASED THERAPIES FOR CKD – THE OLD AND THE NEW

The appropriate application of the KFRE in clinical practice supports early identification of high-risk CKD and allows optimisation of medical therapies that slow progression of CKD, improving mortality and patient outcomes. Until a few years ago the mainstay of treatment of CKD had been largely unchanged for 20 years and centred around optimising blood pressure control with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs),11-14 and optimising comorbid diseases such as diabetes. While ACE and ARB therapies remain a cornerstone of treatment for CKD, the last 5 years have seen the publication of several high-impact clinical trials defining a new era for the treatment of CKD. Sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) are the exemplar medication in that regard,15 but glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) have also been shown to be incredibly effective at improving outcomes for patients with CKD,16 and non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists have shown to be efficacious and safe for patients with diabetic kidney disease.17 If these new medications are implemented as they were in the clinical trials (in addition to maximally tolerated doses of ACE/ARBs) then they will reduce the number of patients progressing to end-stage kidney disease and all adverse health outcomes associated with CKD.

CKD – THINKING ABOUT THE PATIENTS

It has always been the case that in the UK, kidney specialists in hospitals focus on delivering care for select groups of patients with kidney diseases who require highly specialist care. These include patients with end-stage kidney disease, patients with advanced kidney disease not on dialysis, and patients with rare kidney conditions (including vasculitis, glomerulonephritis and genetic diseases such as polycystic kidney disease). While these patients are often very complex and require intensive specialist care, together they account for a very small percentage of patients with CKD. Most patients with CKD are looked after in primary care and will never meet hospital specialist teams. While these patients are usually at low risk of kidney failure, their risk of complications and poorer outcomes related to having CKD are increased.18 Furthermore, awareness amongst the general population of CKD, or indeed what the kidneys do is low.19 As discussed above, we have new ways of identifying patients at risk of their CKD and new treatments to help them, but if the patient’s knowledge of kidney disease is low then it is going to be harder for them to become active partners in their care. This is not limited to tests and drug therapies – there is good evidence that appropriate lifestyle interventions can improve the health, well-being and quality of life for patients with CKD.20

The ability to effectively self-manage was identified as one of the core components for improving outcomes for patients with chronic health conditions in the NHS long-term plan.21 To be able to effectively self-manage, patients need to have:

- Disease specific knowledge to understand what to do and why;

- The skills to perform required tasks or behaviours; and

- The confidence to perform these tasks.22

Together these attributes are described as ‘patient activation’.23 Improving patient activation in patients with CKD is crucial to be able to develop their ability to effectively self-manage, but tools and resources to do this are not immediately available, even in secondary care specialist kidney services.

CKD is already common, but UK modelling suggests that cases are going to increase dramatically over the next 10 years, with increased numbers of patients reaching kidney failure needing dialysis and kidney transplantation.3 The same modelling has shown that effectively implementing kidney-related healthcare interventions such as early identification and risk stratification (e.g. KFRE) and establish patients on evidence-based therapies (including ACEi/ARB and SGLT2i) will save >10,000 lives and ~50,000 quality-adjusted life years over the next decade.3 Engaging patients in programmes that promote effective self-management will be crucial to achieving this and, crucially, this must be implemented in both primary and secondary care.

MY KIDNEYS & ME: AN EFFECTIVE DIGITAL SELF-MANAGEMENT PROGRAM FOR CKD PATIENTS

The last decade has seen major advances in mobile technology and the potential to offer digital healthcare solutions is part of the NHS long-term plan.21 Together with patients and members of the multi-professional team, we co-developed, tested and refined ‘My Kidneys & Me’ (Figure 2), an academic, non-commercial, non-profit-making digital health platform for patients with CKD.24,25 The platform is a theory and evidence-based digital self-management program for patients with non-dialysis CKD that is designed as a 10-week education and behavioural change intervention. The programme is designed to improve the knowledge, confidence and skills of patients with CKD, allowing them to better engage with their healthcare through effective self-management, which will in turn reduce health risks relating to CKD. The program was tested in a multi-centre randomised controlled trial across 26 sites in the UK, recruiting 420 participants. In the trial two-thirds of the participants were given access to the My Kidneys & Me digital health platform, with one-third of patients acting as the control group. Key outcomes were measured in both groups at the start of the trial and after 20 weeks, including the effects of the program on patient activation, kidney-related health, and important health-related behaviours. The results of the trial were extremely encouraging and showed that use of the platform improved patient activation (so crucial to a patient’s ability to effectively self-management) as well as key kidney-specific knowledge and other key health behaviours.26,27 What was also very encouraging was the platform was most effective in patients who started with low patient activation at baseline. This is important as these patients have the most to gain from an effective self-management intervention.

While digital health interventions are an appealing solution for delivering healthcare, consideration must be given to ensuring such solutions are inclusive. Digital poverty, health literacy, and language are key factors that limit access for discrete groups of patients, and quite often these groups are exactly the groups of patients in most need. For these reasons, we are undertaking further revisions of the platform to improve the accessibility for patients with lower health literacy and to make it accessible in different languages. To be truly effective, though, evidence-based interventions such as My Kidneys & Me need to be readily available to patients and implemented across primary and secondary care. Along with revisions to the platform, we are currently undertaking work to establish the best strategies for implementation in different care settings. To do this, we are seeking partner organisations to test strategies and mechanisms to implement the My Kidneys & Me programme in primary and secondary care.

- If you are interested in partnering with us to understand the best ways to make this resource widely available for patients then please get in touch with us at kidneylifestyleteam@leicester.ac.uk

REFERENCES

1. GBD Chronic Kidney Disease Collaboration. Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2020;395(10225):709-33.

2. MacKinnon HJ, Wilkinson TJ, Clarke AL, et al. The association of physical function and physical activity with all-cause mortality and adverse clinical outcomes in nondialysis chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2018;9(11):209-26.

3. Kidney disease: A UK public health emergency. Kidney Research UK report; 2023 https://www.kidneyresearchuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Economics-of-Kidney-Disease-full-report_accessible.pdf

4. NICE NG203. Chronic kidney disease: assessment and management. NICE guideline; 2021 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng203/resources/chronic-kidney-disease-assessment-and-management-pdf-66143713055173

5. Iseki K, Iseki C, Ikemiya Y, Fukiyama K. Risk of developing end-stage renal disease in a cohort of mass screening. Kidney Int 1996 Mar;49(3):800-5

6. Agrawal V, Marinescu V, Agarwal M, McCullough PA. Cardiovascular implications of proteinuria: an indicator of chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 2009 Apr;6(4):301-11

7. Remuzzi G, Benigni A, Remuzzi A. Mechanisms of progression and regression of renal lesions of chronic nephropathies and diabetes. J Clin Invest 2006 Feb;116(2):288-96.

8. Baig A, Zafar A. Urine ACR uptake in patients with a diagnosis of type 1 and 2 diabetes mellitus in a primary care setting: A cross-sectional study. Prim Care Diabetes 2023 Dec;17(6):639-642.

9. Major RW, Shepherd D, Medcalf JF, et al. The Kidney Failure Risk Equation for prediction of end stage renal disease in UK primary care: An external validation and clinical impact projection cohort study. PLoS Med. 2019 Nov 6;16(11):e1002955.

10. The Kidney Failure Risk Equation. https://kidneyfailurerisk.co.uk/

11. Parving H-H, Lehnert H, Brochner-Mortensen J, et al. The effect of irbesartan on the development of diabetic nephropathy in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2001;345:870-878

12. Brenner BM, Cooper ME, de Zeeuw D, et al. Effects of losartan on renal and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 2001;345:861-869

13. Lewis EJ, Hunsicker LG, Clarke WR, et al. Renoprotective effect of the angiotensin-receptor antagonist irbesartan in patients with nephropathy due to type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2001;345:851-860

14. Randomised placebo-controlled trial of effect of ramipril on decline in glomerular filtration rate and risk of terminal renal failure in proteinuric, non-diabetic nephropathy: the GISEN Group. Lancet 1997;349:1857-1863

15. Mark PB, Sarafidis P, Ekart R, et al. SGLT2i for evidence-based cardiorenal protection in diabetic and non-diabetic chronic kidney disease: a comprehensive review by EURECA-m and ERBP working groups of ERA. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2023;38(11):2444-2455

16. Perkovic V, Tuttle KR, Rossing P, et al; FLOW Trial Committees and Investigators. Effects of Semaglutide on Chronic Kidney Disease in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2024;391(2):109-121

17. Bakris GL, Agarwal R, Anker SD, et al; FIDELIO-DKD Investigators. Effect of Finerenone on Chronic Kidney Disease Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(23):2219-2229

18. Sundström J, Bodegard J, Bollmann A, et al; CaReMe CKD Investigators. Prevalence, outcomes, and cost of chronic kidney disease in a contemporary population of 2·4 million patients from 11 countries: The CaReMe CKD study. Lancet Reg Health Eur 2022;20:100438

19. Tuot DS, Wong KK, Velasquez A, et al. CKD Awareness in the General Population: Performance of CKD-Specific Questions. Kidney Med 2019;1(2):43-50.

20. Neale EP, Rosario VD, Probst Y, et al. Lifestyle Interventions, Kidney Disease Progression, and Quality of Life: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Kidney Med 2023 Apr 18;5(6):100643.

21. NHS England. The NHS Long Term Plan; 2019. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/

22. Lightfoot CJ, et al. Patient Activation: The Cornerstone of Effective Self-Management in Chronic Kidney Disease? Kidney Dial 2022;2:91-105

23. Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res 2004;39:1005-1026

24. Lightfoot CJ, Wilkinson TJ, Hadjiconstantinou M, et al. The Codevelopment of "My Kidneys & Me": A Digital Self-management Program for People With Chronic Kidney Disease. J Med Internet Res 2022;24(11):e39657

25. Lightfoot CJ, Wilkinson TJ, Vadaszy N, et al. Improving self-management behaviour through a digital lifestyle intervention: An internal pilot study. J Ren Care 2024;50(3):283-296

26. Lightfoot CJ, Nair D, Bennett PN, et al. Patient Activation: The Cornerstone of Effective Self-Management in Chronic Kidney Disease? Kidney Dial 2022;2(1):91-105.

27. Lightfoot CJ , Wilkinson TJ, Sohansoha GK, et al; SMILE-K collaborators.The effects of a digital health intervention on patient activation in chronic kidney disease. npj Digit Med 2024;7:318