Chronic Kidney Disease: diagnosis and management for general practice nurses

Beverley Bostock

Beverley Bostock

RGN MSc MA QN

Advanced Nurse Practitioner,

Mann Cottage Surgery, Gloucestershire

Council Member, Primary Care Cardiovascular Society

Practice Nurse 2023;53(6):25-29

The first three months following suspicion of CKD in your patient is critical: you need to confirm the diagnosis, optimise blood pressure, instigate statin therapy and initiate medication to protect renal function and prevent further deterioration

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a condition with implications for both renal and cardiovascular health. When diagnosing and managing CKD, the focus needs to be on early and accurate diagnosis and coding, as this increases the possibility of delaying any deterioration in kidney function and optimising cardiovascular risk reduction. In this article we consider how the diagnosis of CKD is made and how it should be managed. By the end of this article, you should be able to:

- Review the pathophysiology of CKD

- Recognise the diagnostic criteria for CKD

- Implement evidence-based recommendations for delaying deterioration in kidney function

- Reflect on the importance of cardiovascular risk reduction in people with CKD

- Determine the complications of CKD

- Support people with CKD to better understand their condition

- Consider when referral into secondary care should be made

THE SIZE OF THE PROBLEM

In the United Kingdom, around 7.2 million people have CKD with around 3.5 million having stage 3, 4 or 5.1 The prevalence of CKD stages 3–5 is around 6%, with more than 90% of those diagnosed being age 60 years and over, and most people having CKD stage 3. In line with the rest of the world, the incidence and prevalence of CKD is increasing. However, around one third to a half of all cases may remain undiagnosed, with women and the elderly being at greater risk of a missed diagnosis.2,3

The number of people with end stage renal disease (ESRD), which requires dialysis, is also increasing, with longer waiting lists for this intervention. Dialysis is, in effect, palliative care as the prognosis for ESRD is very poor, having a worse outlook than breast, prostate or colorectal cancer.4 Treatment with dialysis is very costly for the NHS but more importantly, impacts significantly on the quality of life of both those being treated and their loved ones. A key reason for improving the diagnosis and management of CKD is to facilitate the timely introduction of evidence-based interventions which will prevent further complications and reduce the need for dialysis.

THE ROLE OF THE KIDNEYS IN HEALTH

In health, the kidneys filter 180 litres of blood per day. Each kidney has over 1,000,000 nephrons, with the glomerulus lying within the Bowman’s capsule of each nephron. The afferent arteriole feeds waste-heavy blood into the glomerulus, where filtration is controlled by tubulo-glomerular feedback and the macula densa. Then the efferent arteriole takes blood out from the glomerulus. However, the kidneys do far more than filtering waste and we can summarise their activity using the acronym RENAL:

R – retaining glucose, protein, some vitamins and minerals

E – eliminating waste including medication

N – normalising BP, electrolytes, pH, fluid levels

A – activating the renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS)

L – linking into bone and blood health (calcium, vitamin D, red blood cells [erythropoietin])

It is quickly apparent, then, why people with CKD are at risk of a range of complications, including hypertension and CVD, and why they may go on to be diagnosed with renal anaemia and/or renal bone disease. It should also be clear why prescribers need to consider renal function when prescribing medication, reducing doses of drugs which may not be cleared as a result of impaired kidney function, such as sulfonylureas and direct oral anticoagulants, and initiating medication which can be renoprotective such as ACE inhibitors and sodium glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i).

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR CKD

NICE5 defines CKD as being a reduction in kidney function and/or the presence of structural damage for more than 3 months, with associated health implications. CKD should be diagnosed where there is evidence of kidney damage, such as albuminuria and/or decreased estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) of <60ml/min/1.73m2 for at least 3 months.

It is important to recognise the relevance of this period of 3 months, which reflects the fact that eGFR can rise and fall. It is the sustained reduction in the eGFR which is key. NICE states that if a reading below 60ml/min is recorded for the first time, a second test should be carried out within 1-2 weeks to check for acute kidney injury (AKI). Risk factors for AKI might include an intercurrent acute illness such as influenza or gastroenteritis, or being on medication which might predispose to AKI, such as diuretics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or ACE inhibitors. If the second sample remains below 60ml/min but there is no indication of AKI, the third sample should be tested no sooner than 3 months after the first sample. If that result is also below 60ml/min, the patient can be added to the CKD register. By the time eGFR drops below 60ml/min, nephron mass can be down to 20%, while creatinine starts to rise when nephron mass is down 50% or more.

Consideration of albuminuria is important in the diagnosis of CKD as markers of kidney damage include a urinary albumin: creatinine ratio (ACR) greater than 3 mg/mmol, and/or urine sediment abnormalities such as red blood cells, white blood cells, cellular, fatty, or granular casts or renal tubular epithelial cells.5 NICE recommends that if the ACR is ≥3mg/mmol, it should be repeated in 3 months. If the repeat test again shows an ACR of ≥3mg/mmol, the patients should be diagnosed as CKD with albuminuria.

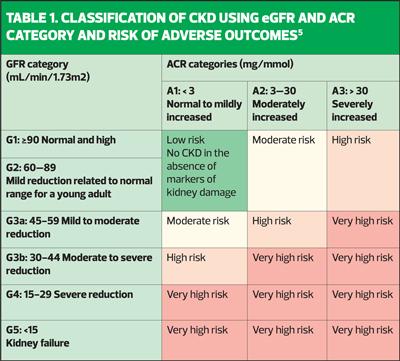

Table 1, adapted from the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) diagram, explains how combining the eGFR and the ACR will give a more holistic overview of the prognosis of CKD (and, incidentally, CVD) for each individual.

Furthermore, the diagram highlights the importance of ACR as an early warning system for kidneys that are under pressure. When the nephrons are struggling, they work extra hard to maintain the eGFR. Thus, the eGFR may appear normal in early kidney disease. However, while the nephrons are battling to maintain the eGFR, they allow protein to fall out into the urine. In health, the kidneys will retain protein, so the presence of albuminuria indicates kidney damage – the higher the level, the greater the damage and the poorer the prognosis. An ACR of 3mg/mmol may be seen with a ‘normal’ eGFR and yet an ACR of 3mg/mmol is associated with a 1.5 x increased risk of heart failure and cardiovascular mortality.5 It is essential, therefore, that clinicians and patients understand why the urine ACR test is vital in assessing kidney health and ensure that the test is carried out at least once a year in people with, or at risk of, CKD.

Haematuria can be a poor prognostic indicator in CKD. An ACR of 30mg/mmol with haematuria warrants a referral as this is associated with an increased risk of mortality and CKD progression. An isolated persistent haematuria needs to be referred within 2 weeks.5

In order to diagnose CKD, then, the patient’s history, risk factors, eGFR and ACR will be taken into account.

RISK FACTORS

Based on the known risk factors for CKD, NICE recommends testing in people with the following conditions.5

- Diabetes

- Hypertension

- Previous episode of acute kidney injury

- Cardiovascular disease

- Structural renal tract disease, recurrent renal calculi or prostatic hypertrophy

- Multisystem diseases with potential kidney involvement, for example, systemic lupus erythematosus

- Gout

- Family history of ESRD (GFR category G5) or hereditary kidney disease

- Incidental detection of haematuria or proteinuria

In people with diabetes, hypertension and heart failure, CKD is a common comorbidity.6 Some relationships are bidirectional i.e., hypertension will adversely affect the kidneys, and CKD will adversely affect the blood pressure. The same can be said for CKD and heart failure. Other known risk factors included ethnicity, deprivation, smoking, obesity, age and exposure to pollution.

PHARMACOLOGICAL MANAGEMENT OF CKD

The management of CKD will depend on the diagnosis being made correctly and registered on the system so that the individual is offered appropriate evidence-based care. The National Kidney Audit showed that people who are not coded correctly are less likely to access that evidence-based care and so are more likely to have worse outcomes, including an increased risk of hospital admissions and a doubling of the mortality level.7 When managing CKD, the focus should be on implementing evidence-based pharmacological interventions which offer cardiorenal protection along with lifestyle changes.

This ‘Alphabet of CKD’ plan offers a simple reminder of the interventions that are known to improve outcomes for people diagnosed with CKD.

A – ACE inhibitor/Angiotensin Receptor Blocker (to maximum tolerated dose)

B – blood pressure (BP) control (aiming for 120/130 mmHg systolic BP)

C – cholesterol lowering medication (atorvastatin 20mg initially)

D – dapagliflozin or empagliflozin (within licence)

E – education and support

F – finerenone (in type 2 diabetes)

ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) work by dilating the efferent arteriole and impacting on the renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS). ACE inhibitors (ACEi) reduce the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II, a potent vasodilator which also facilitates water and salt retention. The effect of ACE inhibition, then, is to reduce vasoconstriction, fluid and salt retention which in turn positively impacts the kidneys, blood pressure and cardiovascular system.8 ARBs affect the RAAS by blocking the effect of angiotensin II. Renal function and BP should be recorded before initiation, and after each dose titration. It is acceptable for eGFR to deteriorate by up to 25% from baseline or for creatinine to rise by up to 30% from baseline as long as bloods are repeated in 1-2 weeks. If changes are greater than this, investigate for other causes e.g., medication or dehydration. If none are found, the medication should be stopped and bloods rechecked in 5-7 days. RAAS inhibition (RAASi) can lead to hyperkalaemia. Previously the advice has been that if serum potassium is 5.0 mmol/L or above, the clinician should:

- Investigate for other causes of hyperkalaemia and treat accordingly

- Stop or reduce the dose of other drugs which may be the cause, and

- Consider reducing the RAAS inhibitors if serum potassium persists at 5.0–5.9 mmol/L or stopping them if serum potassium persists above 6 mmol/L despite these measures.

However, potassium binders such as Patiromir and Lokelma are now available which means that people can potentially stay on RAASi drugs. Optimised doses of RAASi reduce microalbuminuria and slow down further renal impairment.9

Blood pressure should be optimised to evidence-based recommendations: guidelines differ as to the ideal target but a target of between 120mm Hg–129mmHg with a diastolic of 80–90mmHg is generally recommended.10

Cholesterol lowering therapy should be implemented for cardiovascular risk reduction in people with CKD, as CKD can increase the risk of a cardiovascular event. NICE states that lipid lowering therapy (LLT) is indicated for everyone with CKD, with no need to risk assess,5 although the QRisk CVD risk assessment tools do include CKD stage 3 (in QRisk 3) and CKD 4 and 5 (in QRisk 2) as risk factors. When prescribing or recommending statins in people with CKD, it is important to note that renal impairment will increase the risk of myalgia and rhabdomyolysis. If the eGFR is <30ml/min, prescribers should consider getting specialist input before increasing doses of statins. Other LLTs which can be used in CKD in line with their licenses include ezetimibe, bempedoic acid, inclisiran, icosapent ethyl and PCSK9 inhibitors.

SGLT2 inhibitors

Although the mode of action of SGLT2is in CKD is still being studied, it is known that they activate renal tubuloglomerular feedback by increasing the delivery of sodium to the macula densa and improving adenosine production and vasoconstriction in the afferent renal arterioles. This lowers intraglomerular pressure, resulting in reduced hyperfiltration and albuminuria.11 Although all SGLT2i drugs are licensed to treat diabetes, only two are licensed for CKD, dapagliflozin and empagliflozin, both at a dose of 10mg. Dapagliflozin can be initiated down to an eGFR of 15ml/min, empagliflozin down to an eGFR of 20ml/min. The UK Kidney Association recommends SGLT2i use in people with:

- eGFR >60ml/min and ACR 25mg/mmol or higher

- eGFR 45-59ml/min and ACR 25mg/mmol or higher

- eGFR 20-44ml/min irrespective of ACR

- eGFR <20 and ACR 25+

Finerenone

Finerenone is a non-steroidal mineralocorticosteroid receptor antagonist (as opposed to spironolactone and eplerenone which are both steroidal). It was investigated in the FIDELIO-DKD trial, and has NICE approval (TA877) for treating people with type 2 diabetes who have CKD 3-4 with albuminuria. As before, it should be added on to RAAS inhibitors plus an SGLT2i. Finerenone can be initiated down to an eGFR of 25ml/min but should be discontinued if eGFR drops below 15ml/min. Serum potassium should ideally be below 4.8mmol/L but finerenone can be initiated if the potassium is 4.8-5.0mmol/L, with a recommendation to monitor potassium levels and the eGFR at least 4 weekly at first.

EDUCATION AND SUPPORT FOR PEOPLE LIVING WITH CKD

Importantly, anyone diagnosed with CKD needs to know of their diagnosis and what it means. It is likely that the general public might be very fearful of the diagnosis as ‘chronic kidney disease’ is particularly difficult terminology for someone who does not understand it. However, linking CKD to cardiovascular disease might help people to recognise why familiar lifestyle interventions such as smoking cessation, a cardioprotective Mediterranean diet including salt reduction, weight management strategies including increased levels of physical activity, and moderation with regards to alcohol intake are key factors in reducing the risk of both CVD and worsening CKD.

People with CKD should also be reminded about the value of immunisations and why NSAIDs should be avoided (they are nephrotoxic). Clinicians should offer an explanation of the sick day rules, which might include the need to pause the use of their RAAS inhibitors, SGLT2 inhibitors and other drugs which increase the risk of an acute kidney injury in people with renal impairment.

With respect to ongoing monitoring, NICE recommends checking the eGFR, creatinine and ACR as a way of assessing for accelerated progression. This would include an accelerated loss in eGFR of 25% or more and a change in category within 12 months or a sustained decrease in eGFR 15ml/min per year. Both of these could warrant referral to the hospital renal team. In people with CKD 3b, 4 or 5, a full blood count should be ordered at least annually to assess for evidence of anaemia. Evidence of renal anaemia will also require referral for ongoing management. With respect to the risk of renal bone disease, calcium, phosphate, vitamin D, parathyroid hormone should be measured for CKD stage 4 or 5 or sooner if bone disease is suspected and the patient referred in the case of any abnormality.

Other reasons to refer into secondary care include uncontrolled hypertension and suspected renal artery stenosis. If the eGFR drops to <30ml/min, or if the ACR is 70mg/mmol or higher in the absence of diabetes, referral should also be considered. The Kidney Failure Risk Equation is a simple tool which can be used to predict the 5-year risk of needing renal replacement therapy. It is based on age, sex, eGFR and ACR and can be found at https://kidneyfailurerisk.co.uk/. Anyone whose risk assessment reaches over 5% should be referred.

SUMMARY

Chronic kidney disease is an increasing problem in the UK and clinicians need to be aware of the ‘at risk’ groups to ensure that appropriate tests are offered. Once diagnosed, the person with CKD needs to have an explanation of what the condition is and how the link to cardiovascular disease informs our ongoing management. CKD is treated with a combination of medication and lifestyle changes so people need to recognise why drugs are prescribed for cardiorenal protection, even though they may have no symptoms in the early stages. The risk of complications increases as renal function deteriorates so maintaining renal function as far as possible along with cardiovascular risk reduction strategies will optimise the likelihood of positive outcomes.

REFERENCES

1. Kidney Care UK. Facts about kidneys; 2023 https://www.kidneycareuk.org/news-and-campaigns/facts-and-stats/

2. Tangri N, Moriyama T, Schneider MP, et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed stage 3 chronic kidney disease in France, Germany, Italy, Japan and the USA: results from the multinational observational REVEAL-CKD study BMJ Open 2023;13:e067386. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-067386

3. National Institute for Health and Care Research. Chronic Kidney Disease is often underdiagnosed and untreated; 2022. https://evidence.nihr.ac.uk/alert/chronic-kidney-disease-is-often-undiagnosed-and-untreated/

4. Naylor KL, Kim SJ, McArthur E, et al. Mortality in Incident Maintenance Dialysis Patients Versus Incident Solid Organ Cancer Patients: A Population-Based Cohort. Am J Kid Dis 2019;73(6):765–776. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.12.011

5. NICE NG203. Chronic kidney disease: assessment and management; 2021 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng203/

6. Jankowski J, Floege J, Fliser D, et al. Cardiovascular Disease in Chronic Kidney Disease: Pathophysiological Insights and Therapeutic Options. Circulation 2021;143(11):1157–1172. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.050686

7. Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership. National Chronic Kidney Disease Audit; 2017 https://www.hqip.org.uk/former_programmes/national-chronic-kidney-disease-audit/

8. Goyal A, Cusick AS, Thielemier B. ACE Inhibitors. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430896/

9. Rossing P, Caramori ML, Chan JCN, et al. Executive summary of the KDIGO 2022 Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes Management in Chronic Kidney Disease: an update based on rapidly emerging new evidence. Kidney Int 2022;102(5), 990–999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.kint.2022.06.013

10. Carriazo S, Sarafidis P, Ferro CJ, Ortiz A. (2022). Blood pressure targets in CKD 2021: the never-ending guidelines debacle. Clin Kidney J 2022;15(5):845–851. https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfac014

11. Georgianos PI, Divani M, Eleftheriadis T, et al. (2019). SGLT-2 inhibitors in Diabetic Kidney Disease: What Lies Behind their Renoprotective Properties?. Curr Med Chem 2019;26(29):5564–5578. https://doi.org/10.2174/0929867325666180524114033