Child sexual exploitation: safeguarding practice

Marie Doherty

Marie Doherty

MSc, BSc (Hons) Dip Nursing, Senior lecturer of Nursing,

Keele University School of Nursing and Midwifery

Emily Salt

MA Child Care Law BN(Hons) SCPHN (HV)

Lecturer of Nursing,

Keele University School of Nursing and Midwifery

Dr Andrew Finney

PhD, BSc (Hons) Dip Nursing, Senior lecturer of Nursing,

Keele University School of Nursing and Midwifery

Practice Nurse 2023;53(2):22-27

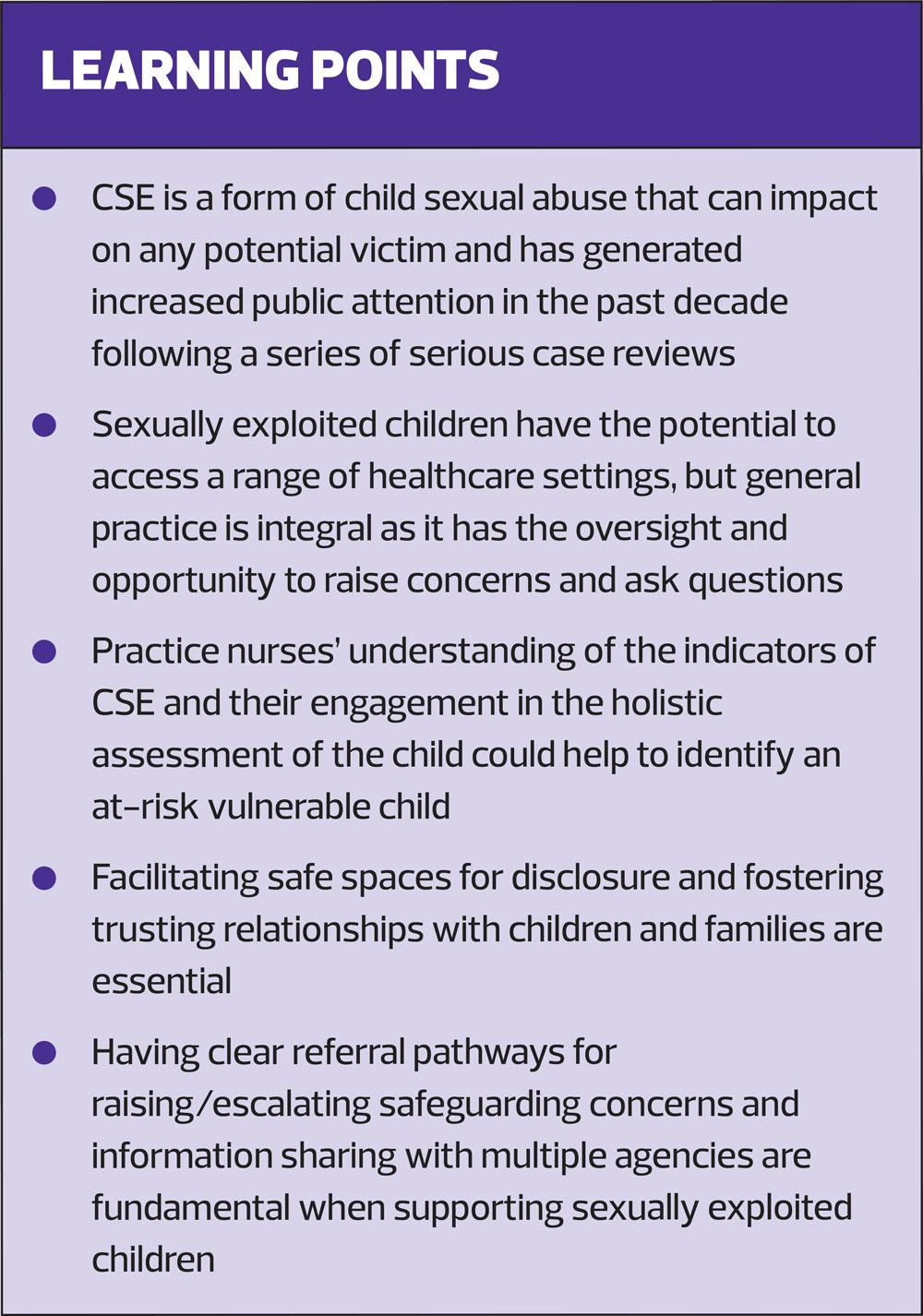

Child sexual exploitation is a significant and contemporary safeguarding issue. Learning from case reviews identifies general practice as a central cohesive source in identifying and supporting at risk children and families

Over the last decade contemporary society has seen a surge in the reports of child sexual exploitation (CSE) in local communities perpetrated by organised networks of offenders.1 High profile CSE cases in areas such as Oldham, Rotherham, Rochdale, Oxford and Telford have peaked public interest and highlighted significant gaps in practitioners’ knowledge and understanding of the complexities surrounding CSE.2

Safeguarding and promoting the welfare of children are paramount, and have been defined as:

- Protecting children from maltreatment

- Preventing impairment of children’s mental and physical health or development

- Ensuring that children grow up in circumstances consistent with the provision of safe and effective care

- Taking action to enable all children to have the best outcome3

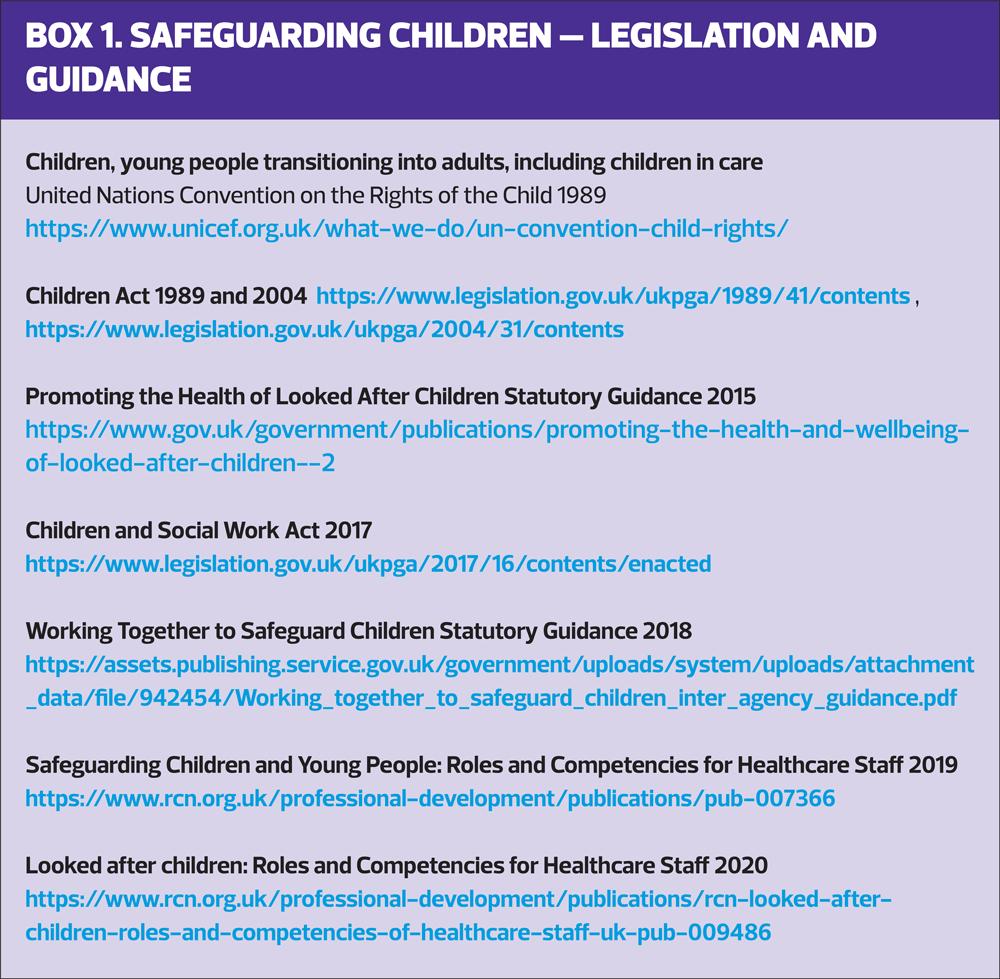

Everyone who comes into contact with children and families has a significant role to play. General practice nurses (GPNs) have contact with children and families across the span of their life course from infancy to adolescence, and are ideally placed to recognise and respond to safeguarding concerns.4 Practitioners are responsible for maintaining their competence in ensuring they execute their duties for safeguarding and promoting the welfare of children, creating a safe environment to raise concerns, and upholding the legislative framework (Box 1).5

CONTEMPORARY SAFEGUARDING ISSUES

Despite mainstream media attention the true extent of CSE is unknown, due to its hidden and complex nature.6 What is acknowledged is the vital role of healthcare professionals (HCPs) in tackling the issue and improving safeguarding practice to protect children from the risk of significant harm. HCPs, including general practice nurses, are perfectly positioned to identify exploited children due to their access to healthcare services for physical and emotional health.

WHAT IS CHILD SEXUAL EXPLOITATION?

Child sexual exploitation (CSE) is a form of child sexual abuse. Sexual abuse may involve physical contact, including assault by penetration (for example, rape or oral sex) or non-penetrative acts such as masturbation, kissing, rubbing and touching outside clothing. It may include non-contact activities, such as involving children in the production of sexual images, forcing children to look at sexual images or watch sexual activities, encouraging children to behave in sexually inappropriate ways or grooming a child in preparation for abuse (including online).

Child sexual exploitation is defined as:

… where an individual or group takes advantage of an imbalance of power to coerce, manipulate or deceive a child or young person under the age of 18 into sexual activity (a) in exchange for something the victim needs or wants, and/or (b) for the financial advantage or increased status of the perpetrator or facilitator. The victim may have been sexually exploited even if the sexual activity appears consensual. Child sexual exploitation does not always involve physical contact; it can also occur through the use of technology.7

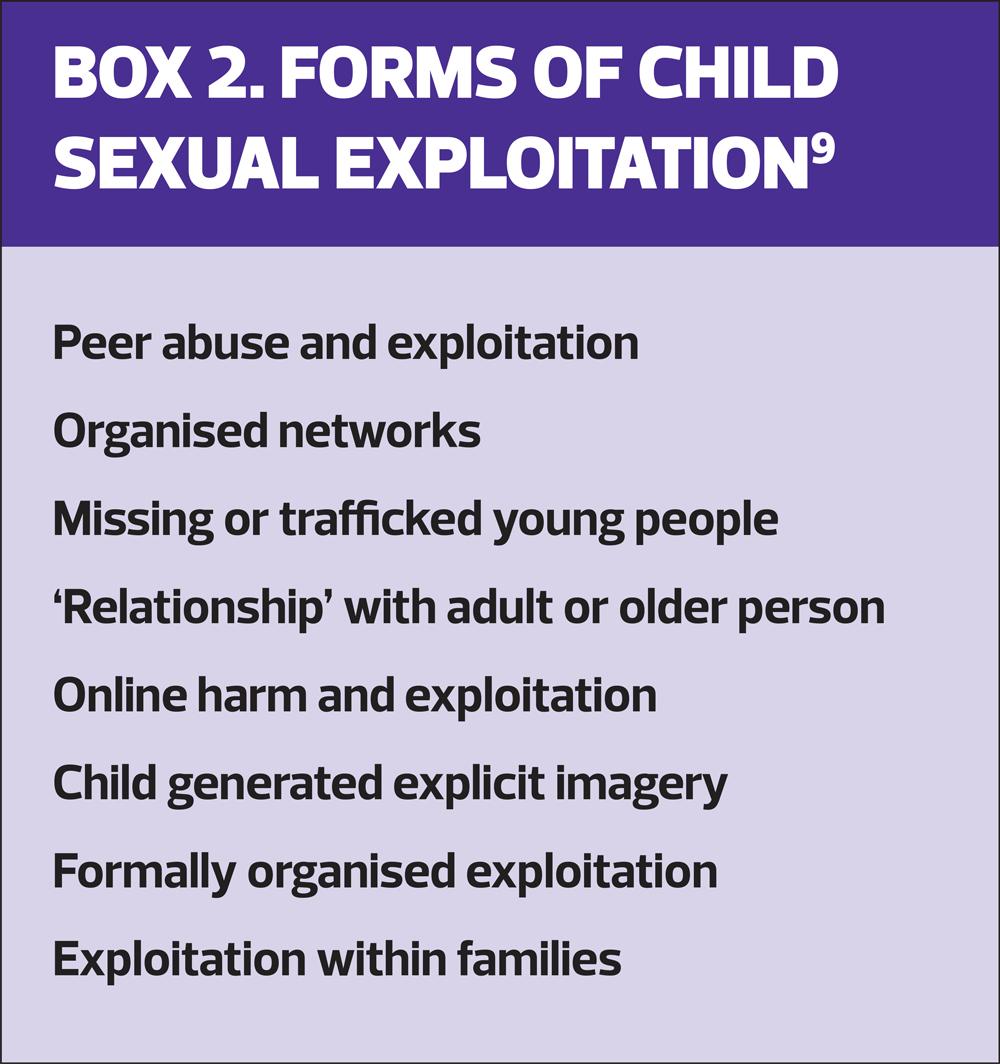

CSE can be perpetrated in a variety of ways which can create a complex interplay for children experiencing it and generate challenges for practitioners who are attempting to identify it.8 Box 2 identifies some of the modes of child sexual exploitation.

How are children sexually exploited?

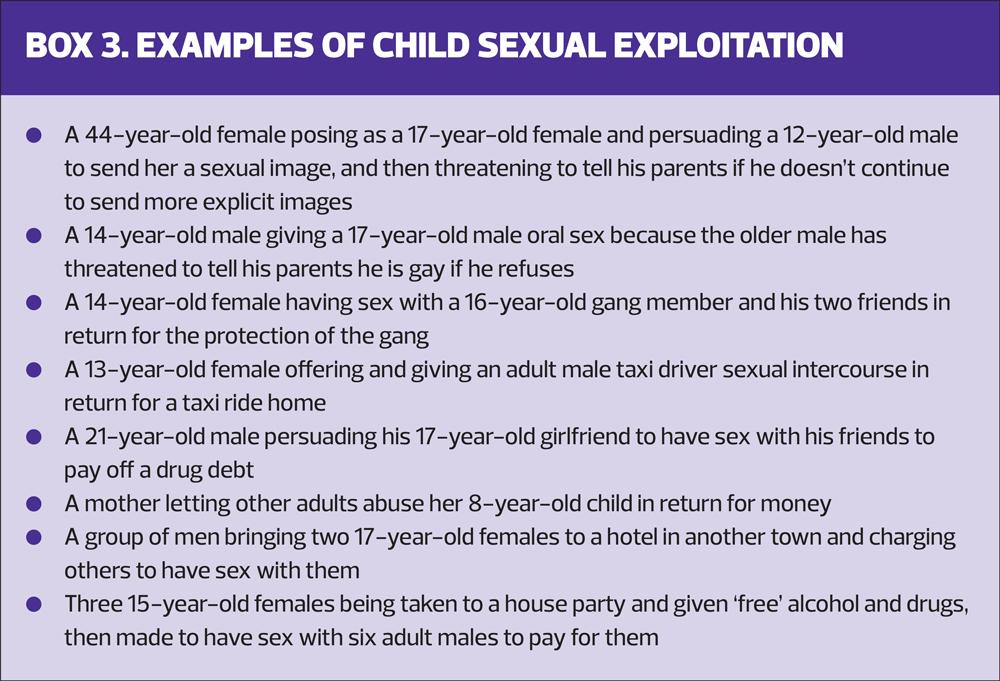

Fundamentally practitioners need to understand that child sexual exploitation can involve individuals or groups who exploit a power imbalance, employing coercive, manipulative and deceptive tactics to force the victim into a situation where they may be unaware of what is happening to them. Lessons learnt from CSE case reviews have highlighted concerns regarding practitioners’ attitudes towards victims of CSE and the perception of exploitative relationships as consensual.10 The appearance of children co-operating with a perpetrator cannot be assumed as consent, as legally they are minors. Practitioners therefore require a deep understanding of the concepts and behaviours linked to coercion, intimidation, power and exploitation in abuse. Illustrative examples of CSE are provided in Box 3, to assist the practitioner in understanding the complexity surrounding concepts of age, gender, power imbalance, coercion and manipulation.7

IDENTIFYING INDICATORS

GPNs have a crucial role in the identification of children at risk of sexual exploitation.

GPNs’ insights into, and understanding of, their patient demographic alongside professional curiosity can be extremely effective in identifying at risk children. A child may present with seemingly benign symptoms from a physical health perspective, which in isolation might not raise safeguarding concerns. The importance of a holistic assessment of the child cannot be overstated.11 Physical signs, behavioural indicators and risks or vulnerability factors must be considered in a holistic assessment framework when identifying CSE.3

Physical Signs

Children and young people seeking support for sexual health issues can be indicative of CSE and abuse.12,13 The presenting symptoms and issues may include:

- Sexually transmitted infections

- Emergency contraception/pregnancy tests/terminations

- Urinary tract infections

- Heavy/irregular vaginal bleeding

- Rectal bleeding

- Abdominal pain14,15

Intended or concealed pregnancy in a child or young person may not only be a consequence of the sexual abuse experienced but viewed by the victim as a resolution to put a stop to the sexual exploitation. Frequency and repetition of these presenting symptoms documented in the electronic patient record must be considered.

Other physical signs may include unexplained injuries categorised under ‘physical abuse’ including:

- Bruises

- Lacerations

- Broken bones

- Burns

- Cuts

- Changes in physical appearance, e.g. weight loss

- Self-harm indicators, e.g. scarring16

Children and young people experiencing sexual exploitation could present with such physical injuries in different care settings in diverse locations e.g. A&E, urgent care or walk in centres, particularly if they are being trafficked across geographical areas. Clinical presentations in these settings may involve the child being intoxicated as perpetrators may employ the use of drugs and alcohol in the sexual exploitation of the child. Substance misuse, eating disorders and self-harm may be present in a child or young person who is being sexually exploited and used as a coping mechanism to manage the impact of the exploitation and abuse. It is therefore vital that GPNs have a comprehensive history of the child’s transitions through these settings and services via robust patient reporting mechanisms.17

Behavioural indicators

CSE has a significant detrimental impact on the mental health and emotional wellbeing of the victim. The trauma they experience has a range of psychological aftereffects including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, flashbacks and psychosis.18,19 Children and young people who are sexually exploited may present in clinical settings with symptoms and behaviours attributed to mental health conditions and /or challenging behaviour. Children and young people with existing mental health issues may be a predisposed target for abusers and perpetrators of sexual exploitation, placing them at increased risk and vulnerability.14,17,19 Challenging behaviours may manifest in a child who appears uncooperative including aggression, ambivalence and withdrawal. Warning signs and indicators of sexual exploitation could be incorrectly attributed to 'normal' adolescent behaviour, reinforcing the need for holistic assessment.20-22

Sexually exploited children and young people may exhibit certain behaviours including:16

- Displaying inappropriate sexualised behaviour for their age

- Being fearful of certain people and/or situations

- Displaying significant changes in emotional wellbeing

- Being isolated from peers/usual social networks

- Being increasingly secretive

- Having money or new things (such as clothes or a mobile phone) that they can't explain

- Spending time with older individuals or groups

- Being involved with gangs and/or gang fights

- Having older boyfriends or girlfriends

- Missing school and/or falling behind with schoolwork

- Persistently returning home late

- Returning home under the influence of drugs/alcohol

- Going missing from home or care

- Being involved in petty crime such as shoplifting

- Spending time at hotels or places of concern, such as known brothels

Parents or carers may not know where their child is, because they have been trafficked around the country.7

IMPACT OF CSE

There are significant long-term consequences of CSE, which can prove devastating for the victim and their family, affecting:

- Physical (including sexual) and mental health and wellbeing

- Education and training and therefore future employment prospects

- Family relationships

- Friends and social relationships, current and as adults; and

- Their relationship with their own children in the future.7

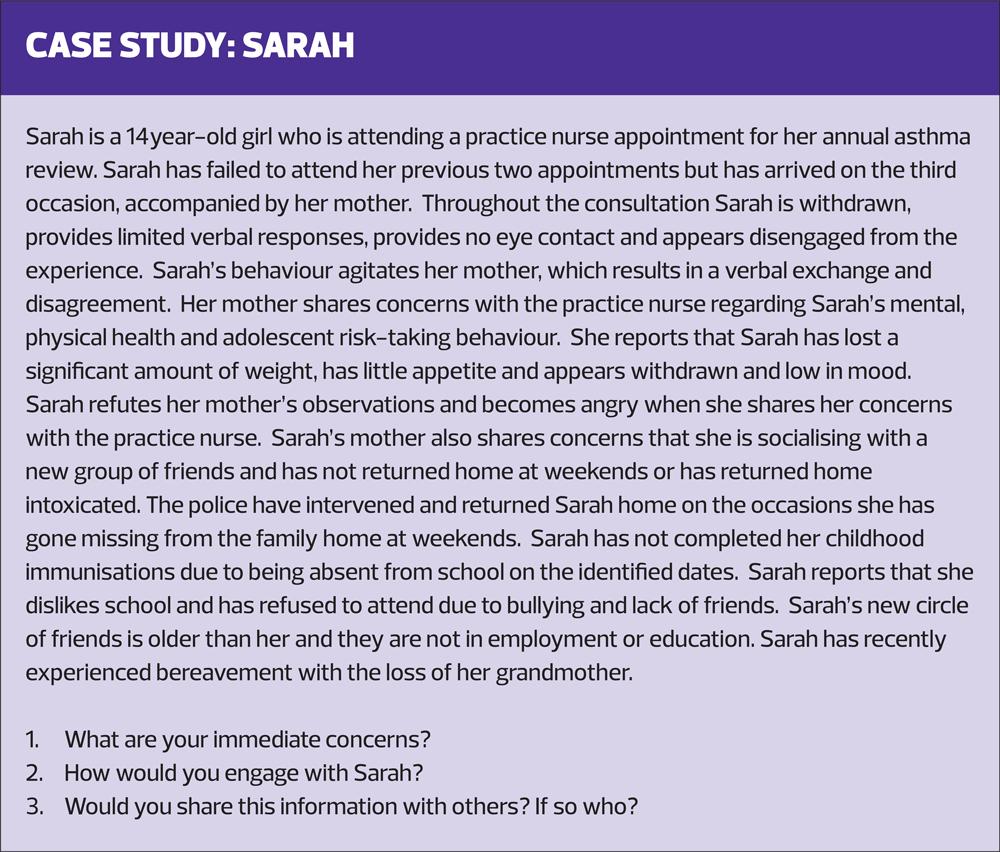

These negative effects may be pertinent to Case study: Sarah (see box) and could impact on Sarah’s global development at this critical stage of adolescent neurological development.23

Children and young people may access a range of healthcare in diverse settings due to the physical and emotional impact of sexual exploitation. Health services remain a consistent provider for children who have disconnected from alternative sources of support. In relation to Sarah, her access to mental health and emotional wellbeing services could now be coordinated by the practice nurse while Sarah is absent from an educational setting and its resources, reinforcing the need for health professionals, including GPNs, to have an understanding of CSE and to create safe environments for disclosure from children and young people.

CHILD FOCUSED RESPONSES

Having explored the complexities surrounding the recognition of CSE, the most vital area of practice is managing a disclosure of CSE and providing an appropriate, safe and supportive response. Sexually exploited children and young people may not identify themselves as victims and refute the allegation that they are being abused and exploited by an individual they trust. Reports of barriers to disclosure include fear of not being believed, feelings of shame and embarrassment and anxiety around the stigma of victim blaming.8

Child sexual exploitation must never be considered the victim’s fault: all children and young people have the right to be protected and safeguarded from maltreatment and abuse.3 Victims report that they want nurses and GPs to be more skilled at asking the right questions. It is important to exercise increased professional curiosity, viewing the child and young person as an intentional being and not a condition or diagnosis. Building therapeutic relationships by ensuring that relevant questions will be asked of the child or young person in order to guide the consultation and to gather their personal views on their health needs can make a positive difference. The basis of this relationship is trust, with the practitioner being careful not to disempower the child and avoiding replication of the abusive power dynamics the child is familiar with through the cycle of abuse.8

Case reviews identify GP practices as integral to the network of services working with children and families. It is vital that practitioners understand the holistic context of the child, and do not focus solely on a child’s physical health needs.10 The case study serves to emphasise this point, Sarah’s physical, social and emotional health needs require attention and could be possible indicators of CSE.

Key issues for the practice nurse in Sarah’s consultation would be:

- Exploration of the family/social context

- Remaining child focused

- Following up missed appointments

- Searching for linking incidents e.g. A&E attendance reports

- Recognising the signs of child abuse, both physical and behavioural

- Sharing information with other agencies

- Working with other agencies to support Sarah

SUMMARY

Child sexual exploitation continues to attract mainstream media attention over the past decade and remains a priority area within the child safeguarding arena. CSE is of particular significance for those health care professionals and practitioners who encounter children and young people and the role of the practice nurse in identifying and protecting children at risk is vital. Children and young people have the right to be protected under the legal and statutory frameworks that exist to guide safeguarding practice. CSE is complex and challenging: GPNs need a thorough understanding of the concepts that are integral to early identification. It is critical in this process to undertake holistic assessment of the child and develop a therapeutic relationship to promote safe spaces for disclosure. Practice nurses can have a significant role in identifying and protecting sexually exploited children and supporting improved outcomes for societies most vulnerable.

REFERENCES

1. Home Office. Child sexual exploitation by organised networks report by the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA): government response; 2022 https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/child-sexual-exploitation-by-organised-networks-report-government-response

2. Radcliffe P, Roy A, Barter C, et al. A qualitative study of the practices and experiences of staff in multidisciplinary child sexual exploitation partnerships in three English coastal towns. Soc Policy Adm 2020;54:1215–1230. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12600

3. HM Government (2018) Working Together to Safeguard Children A guide to inter-agency working to safeguard and promote the welfare of children. Working Together to Safeguard Children 2018 https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/942454/Working_together_to_safeguard_children_inter_agency_guidance.pdf

4. Hunt K. Safeguarding Children - the need for vigilance. Practice Nurse 2014;44(6):18-22

5. NHS England. Safeguarding children, young people and adults at risk in the NHS Safeguarding accountability and assurance framework; 2022. https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/safeguarding-children-young-people-and-adults-at-risk-in-the-nhs-safeguarding-accountability-and-assurance-framework/

6. HM Government. Tackling Child Sexual Exploitation; 2017. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/408604/2903652_RotherhamResponse_acc2.pdf

7. Department for Education. Child sexual exploitation: Definition and a guide for practitioners, local leaders and decision makers working to protect children from child sexual exploitation; 2017. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/child-sexual-exploitation-definition-and-guide-for-practitioners

8. Sharp-Jeffs N, Coy M, Kelly L. Key messages from research on child sexual exploitation: Staff working in health settings; 2017 Centre of expertise on child sexual abuse. London Metropolitan University. https://www.csacentre.org.uk/resources/key-messages/staff-working-in-health-settings/

9. Barnardo’s Cymru. Child Sexual Exploitation: A guide for parents and carers providing care, support and protection to children at risk of or who have been harmed by CSE; 2022.

10. NSPCC Health: Learning from case reviews. Overview of risk factors and learning for improved practice for all professionals working in the health sector; 2015. https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/research-resources/learning-from-case-reviews/health

11. Sangster AM, Crowley M, McGrandles A. The role of sexual health nurses in identifying child sexual exploitation. Community Practitioner 11 June 2018. https://www.communitypractitioner.co.uk/resources/2018/06/role-sexual-health-nurses-identifying-child-sexual-exploitation

12. Kirtley P. “If you shine a light, you will probably find it”: report of a grass roots survey of health staff with regard to their experiences in dealing with child sexual exploitation; 2013. https://riselearningnetwork.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/If-you-shine-a-light-you-will-probably-find-it_-Dr-Paul-Kirtley-for-the-NWG-Network-2013.pdf

13. Nelson S. Tackling Child Sexual Abuse: Radical Approaches to Prevention, Protection and Support. Bristol University Press; 2016. https://policy.bristoluniversitypress.co.uk/tackling-child-sexual-abuse

14. Department of Health. Health Working Group report on child sexual exploitation; 2014. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/284679/35774_2901509_Child_Sexual_Exploitation_Summary_web.pdf

15. Myers J, Carmi E. The Brooke serious case review into child sexual exploitation: identifying the strengths and gaps in the multi-agency responses to child sexual exploitation in order to learn and improve; 2016. https://bristolsafeguarding.org/media/1213/brooke-overview.pdf

16. NSPCC. Protecting Children from Sexual Exploitation; 2021. https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/child-abuse-and-neglect/child-sexual-exploitation#skip-to-content

17. Jay A. Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Exploitation in Rotherham 1997–2013; 2014. https://www.rotherham.gov.uk/downloads/download/31/independent-inquiry-into-child-sexual-exploitation-in-rotherham-1997---2013

18. Royal College of Psychiatrists. Briefing on child sexual exploitation; 2012 London: Royal College of Psychiatrists. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk

19. Marshall K. Child sexual exploitation in Northern Ireland: Report of the Independent Inquiry Belfast: Criminal Justice Inspection, Education and Training Inspectorate and Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority; 2014. https://www.cjini.org/getattachment/f094f421-6ae0-4ebd-9cd7-aec04a2cbafa/Child-Sexual-Exploitation-in-Northern-Ireland.aspx

20. Beckett H, Warrington C. Making Justice Work: experiences of criminal justice for children and young people affected by sexual exploitation as victims and witnesses; 2015. Luton: University of Bedfordshire. https://uobrep.openrepository.com/handle/10547/347011

21. Hickle K. A trauma informed approach, child sexual exploitation and related vulnerabilities; 2016. https://www.uobcsepolicinghub.org.uk/assets/documents/Trauma-Informed-Approach-Briefing-Final.pdf

22. Leon L, Raws P. Boys don’t cry: improving identification and disclosure of sexual exploitation among boys and young men trafficked to the UK; 2016: Children’s Society. https://www.basw.co.uk/resources/boys-don’t-cry-improving-identification-and-disclosure-sexual-exploitation-among-boys-and

23. Best O, Ban S (2021) Adolescence: physical changes and neurological development. British Journal of Nursing 2021;30(5):272-275.

Related articles

View all Articles