Hypertension and chronic kidney disease: an interrelated challenge

Sam Olden, Consultant Practitioner (Rehabilitation and Frailty), HCRG Care Group; Chair of the Clinical Practitioners Special Interest Group and Executive Committee, Ordinary Member British and Irish Hypertension Society | Emily Turner, Lead Pharmacist, Aire Valley Surgery; Member of the Clinical Practitioners Special Interest Group British and Irish Hypertension Society | Karen Jenkins, Consultant Nurse, Kent Kidney Care Centre, East Kent Hospitals University NHS Foundation Trust; Immediate past president Association Nephrology Nurses UK; Honorary member UK Kidney Association | Michaela Nuttall, RGN, Member of the Clinical Practitioners Special Interest Group British and Irish Hypertension Society, Smart Health Solutions

Practice Nurse 2025;55(4):22-25

Hypertension and chronic kidney disease are closely interconnected, and each can amplify the severity of the other. Early recognition and appropriate management will slow progression of kidney disease and reduce cardiovascular risk

Hypertension is not just a risk factor – it is a powerful driver of chronic kidney disease (CKD), and together they form a dangerous, progressive pathway to cardiovascular disease (CVD), kidney failure, and premature death. With 1 in 3 UK adults living with high blood pressure and 1 in 10 affected by CKD,1,2 the burden on individuals and the healthcare system is profound and growing. Early recognition of both hypertension and chronic kidney disease and appropriate management will slow progression of kidney disease and reduce cardiovascular risk.

These conditions often go undetected in their early stages, silently accelerating vascular and organ damage. Left unmanaged, hypertension fuels the decline in kidney function, while CKD amplifies cardiovascular risk. This interconnected spiral presents a significant, but often overlooked, challenge for primary care.

Practice nurses are uniquely positioned at the frontline of recognition and prevention. Their ability to detect early signs, initiate timely interventions, and support lifestyle and treatment adherence is critical to breaking this cycle. Now more than ever, equipping primary care teams with the skills to tackle this dual threat is a top priority.

INTERRELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HYPERTENSION AND CKD

Hypertension is one of the leading causes of CKD, second only to diabetes, due to damage caused to renal microvasculature over time.

In chronic hypertension, arterial stiffening, endothelial dysfunction and glomerular injury leads to loss of nephrons and sclerosis (hypertensive nephrosclerosis). To compensate, the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) is activated contributing to sodium and fluid retention with increased sympathetic tone. This combination further raises blood pressure and produces a self-perpetuating cycle of disease progression if not managed in a timely and appropriate way.

Hypertension and CKD independently increase the risk of cardiovascular disease; the risks are amplified when these coexist. In CKD stages 3-4, individuals are more likely to die from cardiovascular causes than to reach end-stage kidney disease.3 Hence, early and often intensive management is key to improving health outcomes. Positively, when one of hypertension or CKD is managed well, the benefits are concomitant to the other condition.

EARLY DETECTION AND DIAGNOSIS

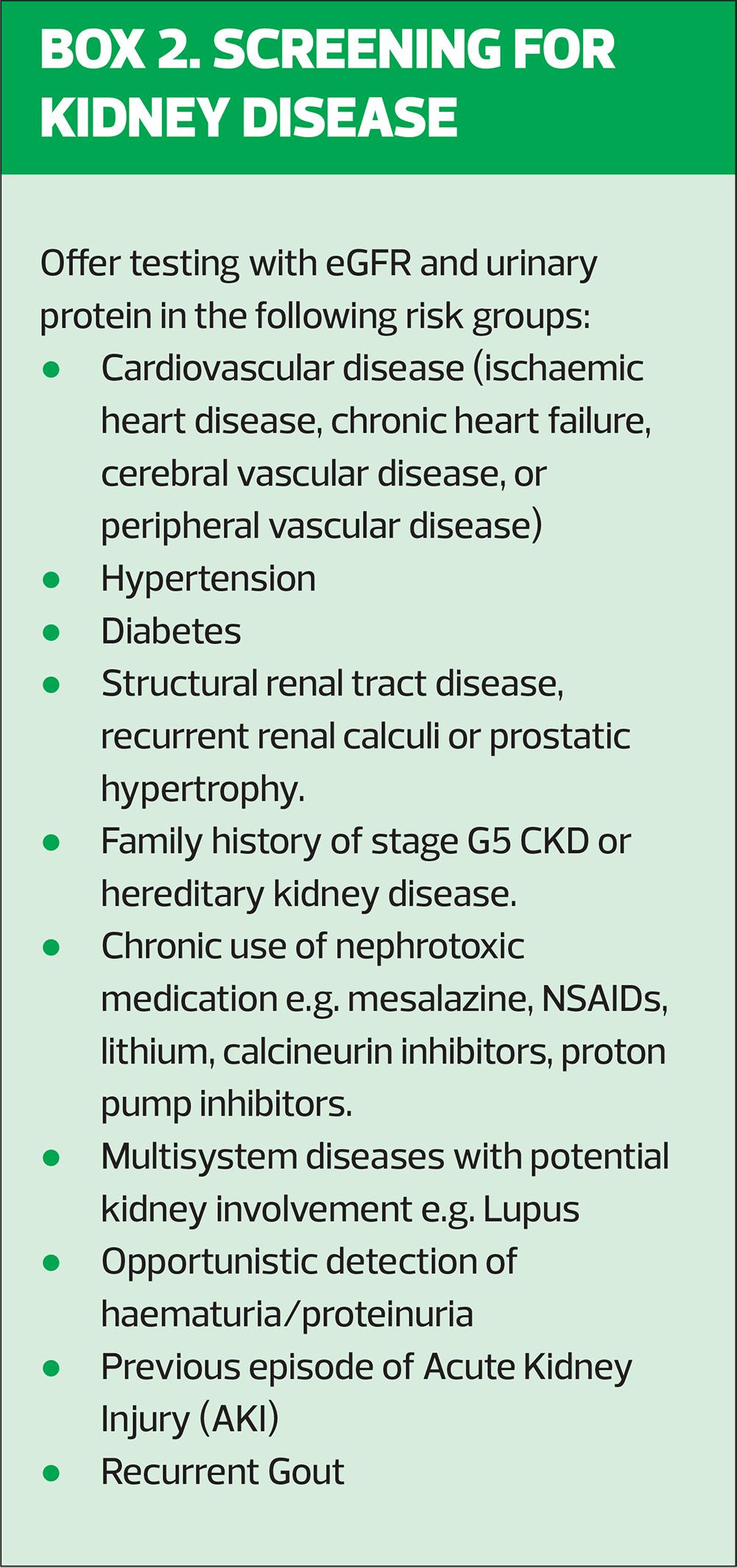

NICE recommends all adults with hypertension, among other risk factors, should be offered annual serum creatinine, eGFR and urine albumin-creatinine ratio (ACR) to screen for CKD.4 Additionally, patients with known CKD should be offered regular blood pressure checks, as there is significant likelihood they will develop hypertension if it is not present already. NICE also provides guidance on how frequently this monitoring should be conducted.

Given blood pressure is central to management of these conditions, it is imperative that accurate measurement is determined using the correct cuff technique (see https://bihs.org.uk/education/basic_training.aspx for videos) and guidance is closely followed for blood pressure management.5,6

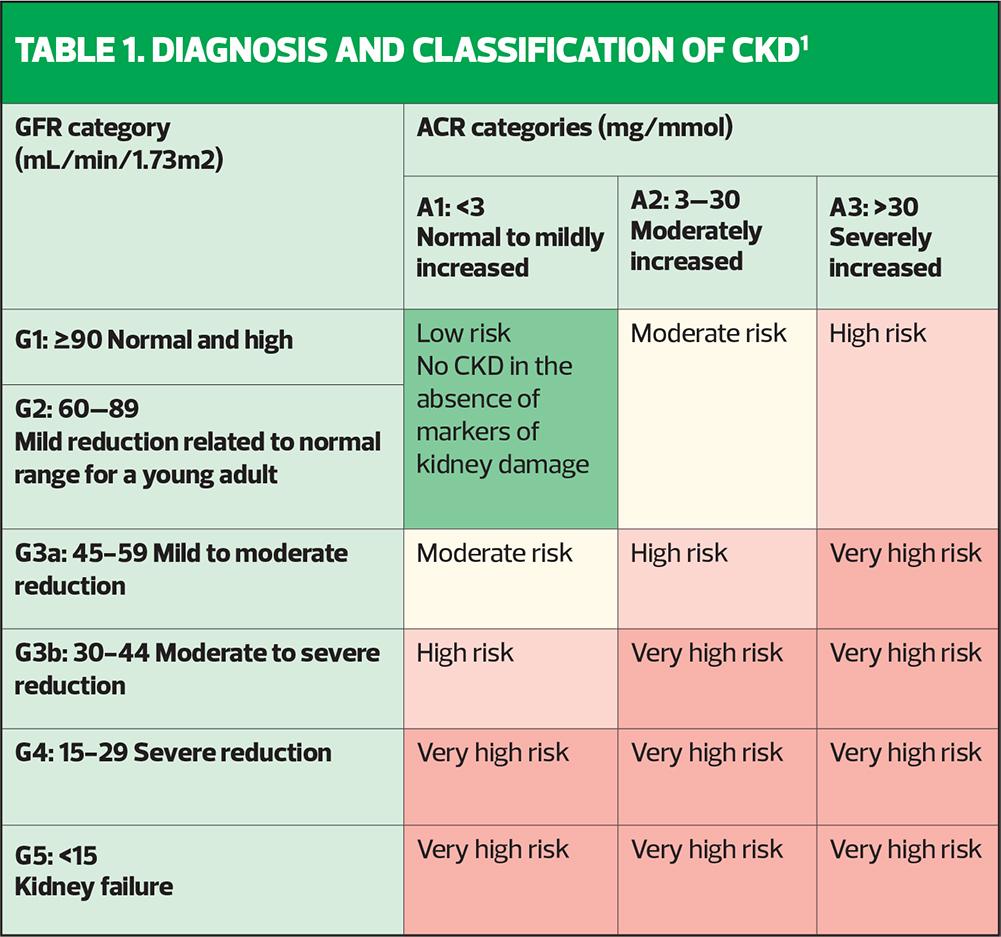

Diagnosis of CKD is done via laboratory evaluation. It is defined as abnormalities of kidney structure or function, present for over 3 months, with implications for health.7 It is classified by changes in estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria and this staging can be used to determine management plans and follow up intensity (see Figure 1).

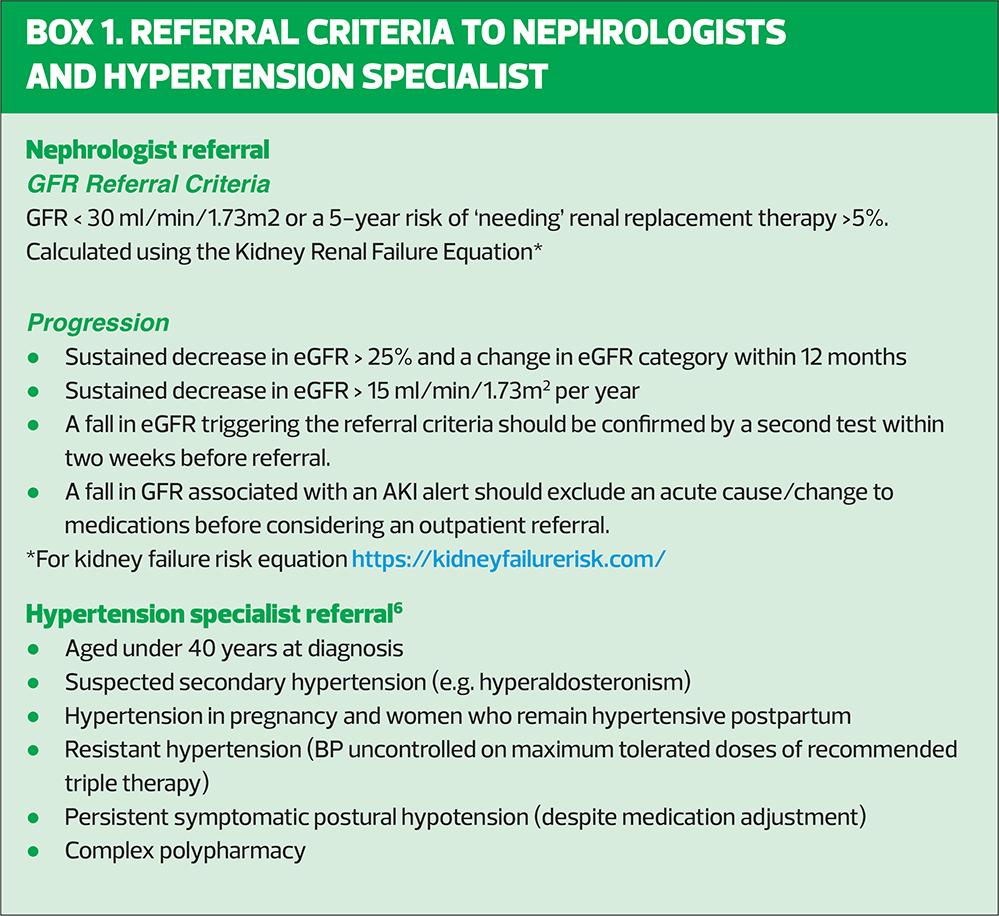

Specifically in people with hypertension, if eGFR is found to be below 60 ml/min/1.73m2, check urinalysis for proteinuria and repeat testing in 2 weeks to confirm if persistent kidney impairment. Anyone having an eGFR check should also have a urine ACR measurement as they may have 'normal' eGFR but raised ACR which is a sign of kidney damage; thresholds for clinical significance also differ if the patient is diabetic (see Box 1).

For assessment and early intervention, it is important to consider whether these conditions are driven by any reversible or secondary causes which need further attention. For example, in hypertension, consider lifestyle factors such as salt intake, obesity, stress or secondary causes such as renal stenosis or endocrine causes. This may need specialist referral, particularly if it is difficult to control blood pressure or the patient is young (see Box 2). Specifically to CKD, consider the impact of diabetes, nephrotoxic medications or other systemic causes of renal impairment (e.g. Lupus) and check for haematuria; again, further assessment or management may require a nephrology referral.

MANAGEMENT OF HYPERTENSION AND CKD

To manage hypertension and CKD in primary care, medication optimisation and lifestyle modification should be implemented in line with guidelines.

Lifestyle interventions form the foundations of hypertension and CKD management; this should include minimising dietary salt intake (aim for <5g per day) and optimising a heart friendly diet. Weight management (BMI <25 kg/m2), regular physical activity (combinations >150 minutes/week of moderate activity, resistance activity and/or vigorous activity) and smoking cessation can also reduce blood pressure and lower cardiovascular risk.

Combining lifestyle change with pharmacotherapy is the preferred management strategy. Blood pressure targets should be set for the patient based on their CKD status, wider past medical history and frailty status, as per national guidance. GPNs should regularly review patients’ blood pressure and review medication for those not meeting target or not tolerating treatment. Clinical inertia is common, and a key role of GPNs should be managing BP quickly and intensively to individualised targets, utilising both lifestyle and medication interventions early.

An evidence-based stepped approach to hypertension pharmacotherapy is recommended in national guidance. Where CKD is present, an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) is the preferred first-line agent. These medications interact with the RAAS to lower blood pressure, decrease intraglomerular pressure and reduce proteinuria, providing an element of renal protection.

NICE and UKKA guidance recommend in adults with hypertension and CKD, with ACR >30 mg/mmol, uptitrating to maximum tolerated RAAS inhibition, irrespective of whether the BP is to target.4,8 In patients who also have diabetes this approach should be taken if ACR is >3 mg/mmol. Alongside this, blood pressure, kidney function and potassium should be monitored within 1-2 weeks of commencing or titrating ACE inhibitors or ARBs.9

Blood pressure control is a key pillar in CKD management, however there are additional controls that should be considered. Glycaemic control is particularly important for those with metabolic disease and can help slow diabetic renal damage. Avoiding nephrotoxins and implementing sick day rules (for example withholding diuretics if vomiting and avoid NSAIDs) can reduce risk of further deterioration.

In later stage CKD, anaemia of chronic disease can present causing fatigue and CKD mineral bone disorder can develop. Monitoring full blood count (FBC), and iron indices in primary care can aid early detection of anaemia of CKD.

Routine measurement of calcium, phosphate, parathyroid hormone and vitamin D levels in adults with a GFR of 30 ml/min/1.73 m2 or more is not recommended in primary care.10

For management of CKD–mineral and bone disorders, seek advice from your local renal service.

There have also been recent developments for the use of SGLT2 inhibitors, which have been shown to slow disease progression in CKD, even in those without diabetes;11,12 these are now recommended in guidance for certain individuals with CKD.

SGLT2 inhibitors also lower BP and have been used as part of a personalised care approach to hypertension management. SGLT2 inhibitors reduce systolic blood pressure by approximately 3.6–5.3 mmHg and diastolic blood pressure by 1.7–2.5 mmHg in patients with hypertension, based on meta-analyses and large real-world studies. The effect can be slightly greater in those with resistant hypertension or proteinuria.13,14

Finerenone, a non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor agonist used in diabetic CKD, may be considered in specialist settings, and in some areas, in primary care. Finerenone has been shown to be more beneficial than ACEi/ARBs alone at slowing progression of CKD.15

ROLE OF THE GPN IN EARLY DETECTION AND ONGOING CARE

Screening

Primary care plays a key role in the ongoing management of hypertension and CKD. Colleagues are well placed to implement simple screening initiatives such as eGFR and urine ACR tests for hypertensive patients as part of annual long term condition reviews. Systematic screening can also help to detect CKD at early stages where intervention is most effective.

Patient Education

Practice nurses can also play a key role in education for patients with or at risk of CKD and hypertension. This can include teaching on how to monitor blood pressure correctly, what test results mean and knowledge sharing on lifestyle change for management and prevention of conditions. Patients are often unaware of the connection between hypertension and kidney disease.

Medicines Optimisation

Medication adherence remains a significant challenge in hypertension and CKD management; GPNs can be pivotal in supporting improved adherence to medication regimes. This could include education on purpose and impact of medication, being available for patients to discuss concerns about medications and side effects, supporting adherence screening initiatives, consistent review of medications and, if prescribers, participating in optimisation of medication regimens.

Coordinating care

Currently cases of early CKD go undetected often until eGFR drops significantly. Practice nurses often play an instrumental role in coordinating the MDT around the patient, and therefore appropriate knowledge in the evidence and management for hypertension and CKD can lead to more effective early intervention and specialist referral.

CONCLUSION

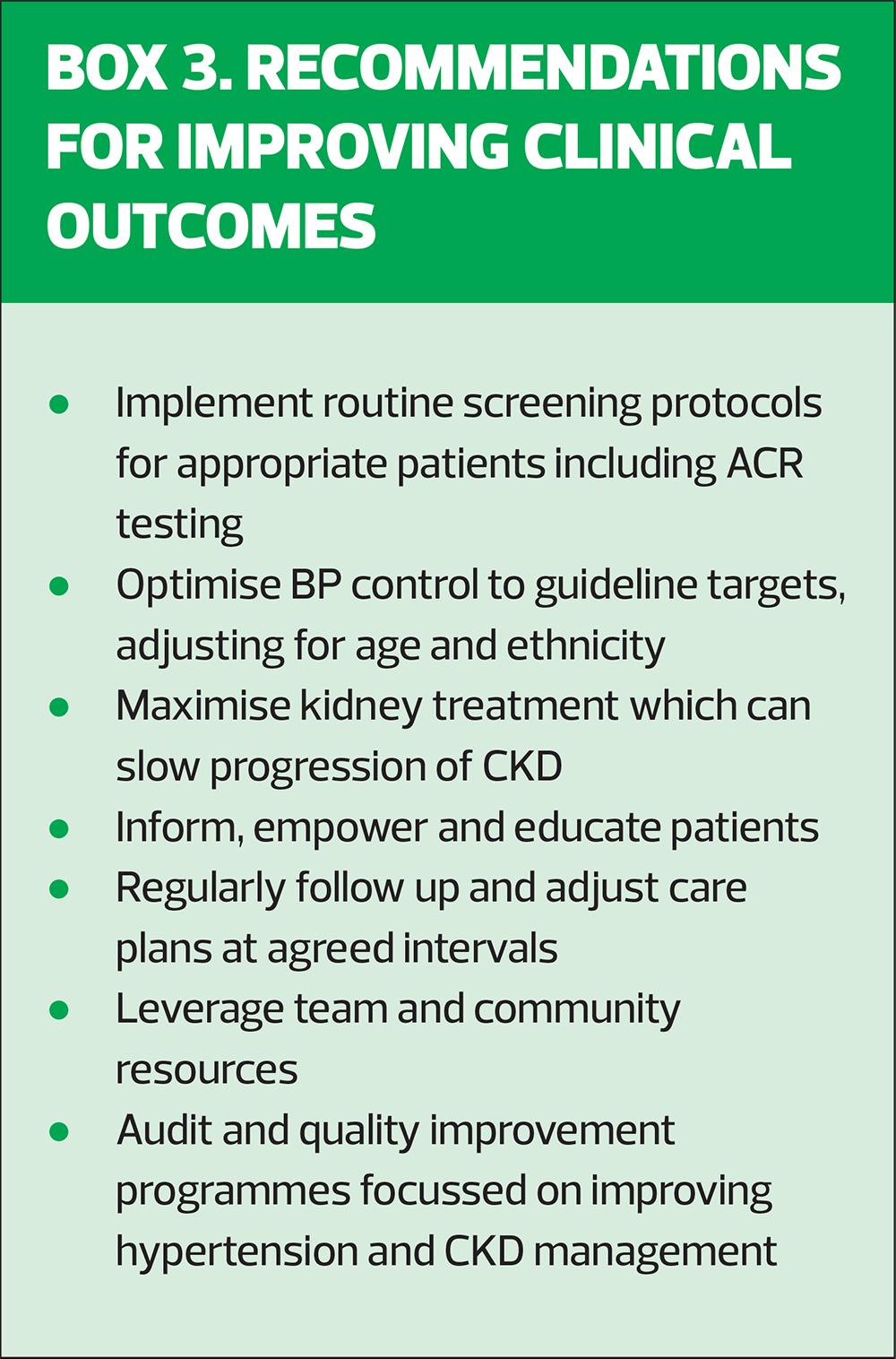

Hypertension and chronic kidney disease present a challenging and entwined relationship that benefits significantly from early detection and intervention as well as close monitoring. It is important for healthcare professionals and patients to understand the interrelationships between these two pathologies and the bilateral relationship of progression or treatment between the two.

Hypertension is a silent killer and if left unmanaged can cause kidney damage that can make management of blood pressure more challenging. Likewise, kidney disease – if not managed closely – can drive hypertension and amplify kidney impairment.

Optimal management of hypertension and CKD requires a careful balance of lifestyle modification, pharmacotherapy, patient engagement and specialist input. Primary care is well placed to support this patient journey and optimise shared decision making in condition management.

The use of national guidelines can help create a suitable pathway and processes for assessment, early intervention and optimal management that is both evidence-based and up to date. Early detection with intensive risk management by achieving blood pressure targets and protecting kidney function will lead to significantly improved outcomes for patients and their families.

Achieving optimal outcomes and delaying progression of disease relies on empowering patients through education, self-awareness of their condition and shared decision making for treatment options. An informed and engaged patient who takes ownership of their blood pressure and kidney health experiences fewer complications and reduces the burden on services, patients, their carers or families.

The landscape for hypertension and CKD is a dynamic and evolving one, and there continue to be exciting advances for novel therapies, which in turn influence and refine the guidelines. Therefore, to best support patients, healthcare professionals should continue to engage with evidence-based practice and recommendations from leading organisations in their respective fields such as UKKA and BIHS.

- Find out more about BIHS and UKKA and their partnership here: British and Irish Hypertension Society (BIHS) and The UK Kidney Association (UKKA) join forces for prevention https://bihs.org.uk/news/15/british_and_irish_hypertension_society_bihs_and_the_uk_kidney_association_join_forces_for_prevention_ukka

References

- NHS England. Health Survey for England, 2021 part 2. NHS Digital. 2023. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/health-survey-for-england/2021-part-2/adult-health-hypertension

- Kovesdy CP. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: an update 2022. Kidney Int Suppl. 2022;12(1):7–11.

- BMJ Best Practice. Chronic kidney disease; 2025. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/topics/en-gb/84

- NICE NG203. Chronic kidney disease: assessment and management; 2021. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng203

- NICE NG136. Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management; 2023. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136

- Lewis P, George J, Kapil V, Poulter NR, et al. Adult hypertension referral pathway and therapeutic management: British and Irish Hypertension Society position statement. J Hum Hypertens. 2024;38:3-7.

- Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2024 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney Int. 2024;105;117-314.

- UK Kidney Association. UK eCKD Guide;2024. https://www.ukkidney.org/health-professionals/information-resources/uk-eckd-guide

- NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Angiotensin-II receptor blockers; 2025. https://cks.nice.org.uk/topics/hypertension/prescribing-information/angiotensin-ii-receptor-blockers/

- Heerspink HJL, Stefánsson BV, Correa-Rotter R, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(15):1436–1446.

- The EMPA-KIDNEY Collaborative Group. Empagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2022;388(2):117–127.

- Zhang Q, Zhou S, Liu L. Efficacy and safety evaluation of SGLT2i on blood pressure control in patients with type 2 diabetes and hypertension: a new meta-analysis. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2023;15(1):118. doi:10.1186/s13098-023-01092-z.

- Baker WL, Buckley LF, Kelly MS, et al. Effects of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors on 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(5). doi:10.1161/JAHA.117.005686.

- Bakris GL, Agarwal R, Anker SD, et al. Effect of finerenone on chronic kidney disease outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(23):2219–2229.

Related articles

View all Articles