Cardiovascular disease – identification and treatment of people at high risk

Beverley Bostock

Beverley Bostock

RGN MSc MA QN

Nurse Practitioner, Mann Cottage Surgery

Education Facilitator Devon Training Hub

Primary Care Cardiovascular Society Council Member

Professor Ahmet Fuat

MBChB PhD FRCGP FRCP (London) FRCP (Edinburgh) FPCCS PGDiP Cardiology DRCOG DFFP CertMedEd

Honorary Professor of Primary Care Cardiology, Durham University

GP, GP Appraiser and GPSI Cardiology Darlington

Past President Primary Care Cardiovascular Society

Practice Nurse 2021;51(3):20-24

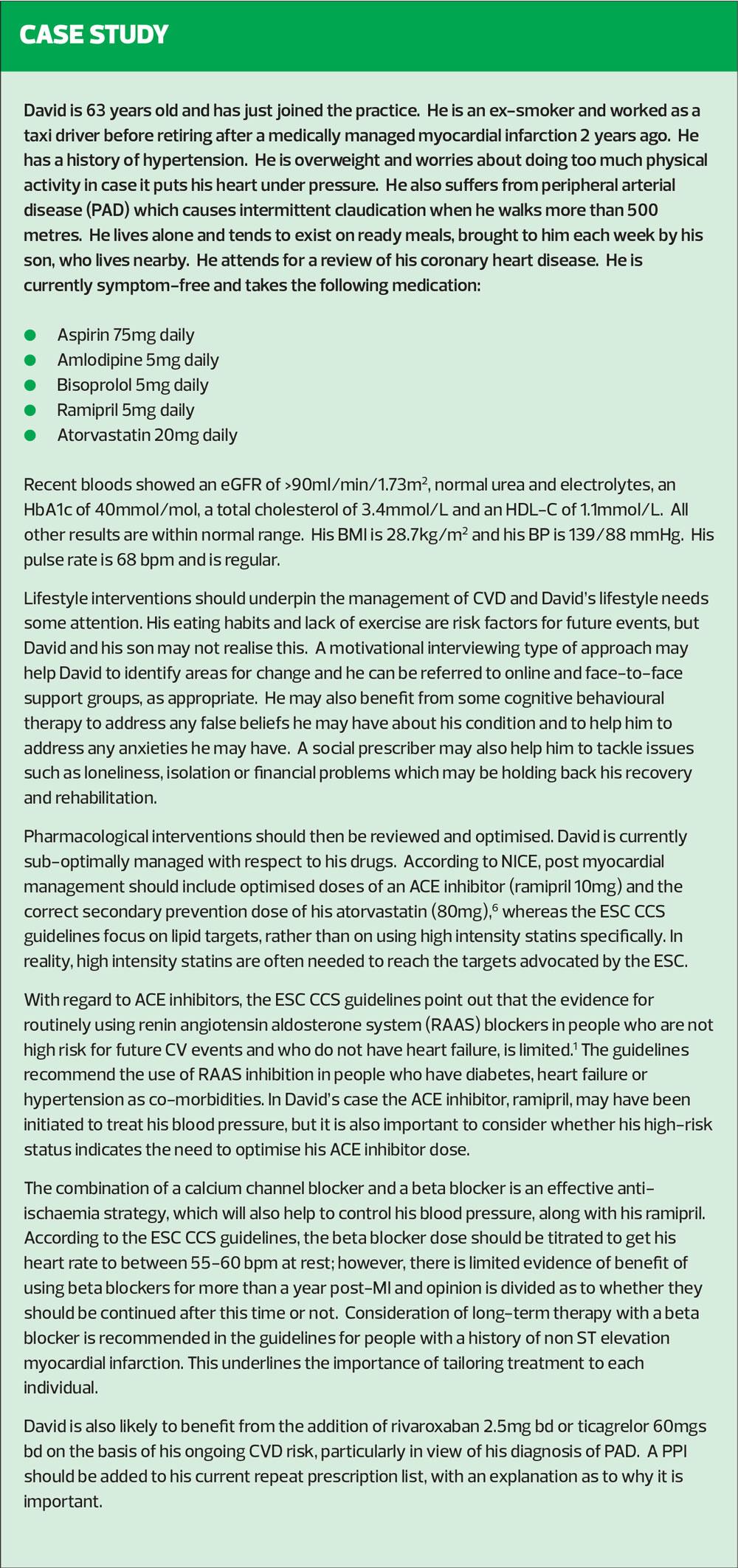

In the last issue, we provided an update on primary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD). In this article, we focus on risk factor management for people with established CVD, with the aim of preventing further cardiovascular events

Many general practice nurses (GPNs) are involved in identifying people at risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and supporting those individuals to manage their risk factors. Furthermore, people living with established cardiovascular disease are usually managed in general practice, with GPNs being responsible for reviewing them and ensuring that best practice is implemented. GPNs can advise on lifestyle interventions such as healthy eating, weight loss, physical activity, smoking cessation and alcohol intake. Whether prescribers or not, GPNs will also be able to advise on medication, reviewing and optimising pharmacological interventions to ensure that research is put into practice in order to optimise outcomes.

In this article we review the evidence for secondary prevention of CVD in asymptomatic people with established coronary artery disease and consider the place of blood pressure and lipid management, the use of antiplatelet and anticoagulant drugs and the role of lifestyle interventions to reduce future cardiovascular events.

Particular reference is made to recommendations in the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes.1 These guidelines were revised in 2019 to focus on chronic coronary syndromes (CCS) instead of on stable coronary artery disease (CAD). The guidelines focus on six key presentation of CCS:

i. Patients with suspected CAD and stable angina symptoms and/or dyspnoea

ii. Patients with new onset heart failure or left ventricular dysfunction and suspected CAD

iii. Patients with stabilised symptoms less than 1 year after an acute coronary syndrome or those with recent revascularisation

iv. Patients more than 1-year post-diagnosis or revascularisation

v. Patients with angina and suspected vasospastic or microvascular disease

vi. Asymptomatic patients who are diagnosed with CAD via screening

The focus of this article will be on those falling into category iv – those who are more than 1-year post diagnosis or revascularisation.

By the end of this article, readers should be able to:

- Recognise the main causes of CVD

- Analyse how risk factor management can reduce future risk of CV events

- Consider the key drug therapies that may be needed for people with established CVD

- Evaluate the place for lifestyle interventions in reducing CVD risk

- Implement evidence-based guidelines in practice in a tailored and person-centred way

WHAT CAUSES CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE?

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is an umbrella term covering conditions which result from the build-up of atherosclerotic plaque in the blood vessels of the body, including the large vessels supplying the brain, heart and limbs, and the smaller vessels supplying the eyes, kidneys and nerves.2 Chronic kidney disease (CKD) and erectile dysfunction have now been recognised as being predictors of cardiovascular events.3 Key contributing factors to the development of atheroma include hypertension, dyslipidaemia, smoking, poor diet, obesity and lack of physical activity.2 CVD is the cause of high levels of morbidity and mortality in the United Kingdom leading to Public Health England identifying CVD risk reduction as a priority for the NHS, with the publication of its 10-year plan in 2019.4 (See A clinical priority: cardiovascular disease prevention, Practice Nurse February/March 2021.) Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on the prevention, detection and management of CVD, which will mean that increasing numbers of people will be at risk of events which could have been avoided.5 The pandemic has also caused disruption across the CVD pathway and widened regional inequalities. Analysis finds 470,000 fewer new prescriptions (people commenced on a medication for the first time) of preventative cardiovascular drugs such as antihypertensives, statins, anticoagulants and oral anti diabetics in the last year.6 GPNs and others working in primary care should therefore be aware of opportunities to identify people who have not been diagnosed as well as recognising the importance of undertaking thorough reviews of those people with an established diagnosis of CVD.

PREVENTION OF FURTHER CARDIOVASCULAR EVENTS

People who have been diagnosed with cardiovascular disease in one arterial bed will be at increased risk of having atherosclerotic disease in other areas of the body. An existing diagnosis of CVD also means that there is an increased risk of a further event. The ESC guidelines on chronic coronary syndromes (CCS) note that the risk of further CV events is likely to increase if risk factors are poorly managed and decrease if they are successfully addressed.1 The focus on ‘chronic coronary syndromes’ instead of using the previous terminology of stable coronary artery disease reflects the fact that CVD is a dynamic process of plaque development and accumulation, which can be addressed both pharmacologically and through lifestyle measures. In some patients, revascularisation procedures are also recommended. The pharmacological and lifestyle interventions recommended in this article are based on those from the ESC CCS guideline, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the 2016 European Guidelines on CVD prevention in clinical practice.1,7,8 Treatment outcomes are based on symptom control and prevention of future CV events.

Managing blood pressure

High blood pressure (hypertension) is suspected if an individual has a clinic blood pressure of 140/90 mmHg or more.9 Clinic readings should be followed up with 24 hour ambulatory BP or 7 days’ twice daily home BP readings to ensure that there is no ‘white coat’ effect causing the raised BP that has been recorded in the clinical setting. Diagnosis can only be confirmed if clinic BP of 140/90 mmHg or more and 24 hour ABPM or 7 days average HBPM 135/85 mmHg or over. The decision to treat an individual’s BP will depend on what stage hypertension they have (stage one, where home readings are between 135/85 – 149/94 mmHg or stage two, where home readings are over 150/95 mmHg), their cardiovascular risk score and the presence of pre-existing conditions such as cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease or diabetes.8 The NICE hypertension guidelines do not differentiate between targets for people with and without cardiovascular disease or diabetes, advising a generic target of less than 140/90 mmHg in clinic or less than 135/85 mmHg at home in patients 79 years and younger or 150/90 mmHg in clinic or less than 145/85 mmHg in patients over 80 years old. The ESC hypertension guidelines recommend aiming for less than 140/90 mmHg initially and then, if treatment is tolerated, aiming for 130/80 mmHg or lower.10 In people under the age of 65, the ESC hypertension and chronic coronary syndrome guidelines recommend aiming for a systolic BP of 120-129 mmHg, with a diastolic of less than 80 mmHg. Untreated hypertension is linked to an increased risk of stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure and other conditions. Many people with hypertension will need at least two drugs to get them to target.11

Lipid management

In people with known CVD, lipid management should be initiated irrespective of their lipid profile, because they are at high risk of future events. ESC dyslipidaemia guidelines recommend that in people with established CVD or at very high risk, a minimum 50% reduction in LDL-C from baseline and an absolute LDL-C treatment goal of <1.4 mmol/L should be aimed for. For patients at high risk, an LDL-C goal of <1.8 mmol/L is recommended.12

The ESC guidelines on CCS recommend that if target lipid levels are not achieved using a high intensity statin, ezetimibe should be added. Ezetimibe has been shown to reduce LDL-cholesterol and the risk of CV events.13 The addition of a PCSK-9 inhibitors may also be indicated for a small number of patients.14

The role of antithrombotic therapy

The ESC guidelines on CCS recommend that a second antithrombotic drug should be considered in addition to aspirin for long-term secondary prevention in patients who are at high risk of future ischaemic events, but who are not high risk for bleeding, and may be considered for those who are at moderate risk of future ischaemic events but who are not high risk for a bleed.

In patients who are on aspirin, dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), or oral anticoagulants, and who are at high risk of bleeding, a proton pump inhibitor should be initiated.

Anticoagulants inhibit the formation of clots and have been shown to reduce the risk of vascular events. The use of low dose anticoagulants for secondary prevention of CVD along with antiplatelet therapy has been identified in the ATLAS ACS 2–TIMI 51 trial where rivaroxaban 2.5mg bd was shown to reduce major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in patients with acute coronary syndrome who were already treated with aspirin and clopidogrel.15 Furthermore, the Cardiovascular Outcomes for People Using Anticoagulation Strategies (COMPASS) trial compared rivaroxaban 5mg bd alone, with aspirin 100mg daily alone and with a combination of both aspirin 75mg and rivaroxaban 2.5mg bd in people with CCS or peripheral arterial disease (PAD). The combination of aspirin and rivaroxaban led to a decrease in ischaemic events and although bleeding events were increased, they were non-fatal bleeds. The greatest benefits were seen in people with other CV risk factors such as diabetes, PAD or moderate chronic kidney disease (CKD).16 Furthermore in patients with a myocardial infarction more than 1 year previously, treatment with ticagrelor 60mgs twice daily significantly reduced the risk of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke but did increase the risk of major bleeding.17

Post-MI secondary prevention

Dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) is recommended post MI, using aspirin plus a P2Y12 inhibitor, such as clopidogrel, prasugrel or ticagrelor. Not all patients respond to clopidogrel, however, and proton pump inhibitors, particularly omeprazole and esomeprazole, can negatively impact on the response too. Prasugrel is more effective than clopidogrel but is associated with a higher risk of bleeding. Ticagrelor may offer the best overall risk: benefit profile but this will depend on the individual patient and their previous cardiovascular diagnosis and management. The duration of DAPT will also need to be assessed individually, weighing up the benefits of treatment versus the increased risk of bleeding. Hospital notes should be consulted to ensure that patients are treated appropriately and that any treatment does not extend beyond the recommendations made by the consultant on discharge.1

Lifestyle interventions

While medication plays an important part in reducing blood pressure and lipid levels, the impact of lifestyle interventions should not be underestimated. There is currently an increased level of interest in low carbohydrate diets and further research is anticipated on this topic. Low carbohydrate diets can help with weight loss and also impact on lipid levels.18

Healthcare workers might consider recommending that time-constrained individuals consider high intensity interval training (HIIT) as a less time-consuming but evidence-based way of including exercise in their daily routine in order to improve health.19

Smoking cessation is one of the most important and cost-effective interventions known to improve health and Public Health England has expressed concern at the reduction in general practice-led quit attempts in recent years.18 Smoking cessation is not the remit of one service; all healthcare providers should offer smoking cessation support unless they have a good reason not to.

THE ANNUAL REVIEW

The annual review provides an opportunity to consider how well the patient’s symptoms are controlled and whether effective secondary prevention interventions are in place, based on latest evidence and guidelines. These interventions should include both pharmacological and lifestyle management. Adherence to both should also be assessed, with the focus on motivational interviewing, and taking a person-centred approach. Up to date bloods including a full blood count (as haemoglobin and white cell count have been shown to predict prognosis in people with CCS),19 renal function, lipid profiles and HbA1c (as many people with CVD will be high risk for diabetes) should be available. An annual ECG is desirable to assess heart rate and rhythm, although increasing numbers of patients will have smart technology (watches or portable ECG event recorders) to assess their own readings. The ESC guidelines also recommend 3-5 yearly echocardiography in people with established CVD, although this may not be common practice in the UK.1

Primary Care Networks have enormous potential to deliver care in a targeted way, for the populations they serve. Their challenge is to look at how evidence and guidelines are implemented in a person-focused and cost-effective way and to support clinicians and practices in this aim.

CONCLUSION

Cardiovascular disease results from a range of modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors. The focus for primary care should be to work with colleagues in order to

- Prevent future events

- Implement evidence based care to reduce symptoms

- Support individuals with lifestyle changes via the multi-disciplinary team

- Optimise pharmacological interventions to reduce future risk

This can only come from an educated and empowered multi-disciplinary team. The Primary Care Cardiovascular Society https://pccsuk.org/ aims to support clinicians, Primary Care Networks and the evolving Integrated Care Systems to deliver first class care in cardiovascular disease. It supports the idea of a network of CVD champions from within GP practices, across PCNs and beyond to share knowledge, expertise and best practice throughout the health service. If you would like to know more, or would like to be involved, please contact us on president@pccsuk.org or admin@lcwconsulting.co.uk.

An educated workforce is a prerequisite to optimising cardiovascular outcomes.

REFERENCES

1. Knuuti J, Wijns W, Saraste A, et al, for the ESC Scientific Document Group. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J 2020;41(3):407–477. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz425

2. World Heart Federation. Risk factors; 2017 https://www.world-heart-federation.org/resources/risk-factors/

3. Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C, Brindle P. Development and validation of QRISK3 risk prediction algorithms to estimate future risk of cardiovascular disease: prospective cohort study BMJ 2017;357:j2099 doi:10/1136/bmj.j2099

4. Waterall J. The 10-year CVD ambitions for England – one year on; 2020 https://publichealthmatters.blog.gov.uk/2020/02/06/the-10-year-cvd-ambitions-for-england-one-year-on/

5. American College of Cardiology. Studies Highlight Increase in CVD Deaths, Reduction in Diagnoses During COVID-19 Pandemic; 2021. www.acc.org/latest-in-cardiology/articles/2021/01/11/20/03/studies-highlight-increase-in-cvd-deaths

6. Patel P, Thomas C, Quilter-Pinner H. Without skipping a beat: the case for better cardiovascular care after coronavirus; March 2021 www.ippr.org/research/publications/without-skipping-a-beat

7. NICE CG181. Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and reduction, including lipid modification; 2016 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg181

8. Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al. 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: The Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice. Eur Heart J 2016;37(29):2315–2381. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehw106

9. NICE NG136. Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management; 2019 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng136

10. Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, et al, for the ESC Scientific Document Group. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur Heart J 2018;39(33):3021–3104. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy339

11. Mancia G, Rea F, Corrao G, Grassi G. Two-Drug Combinations as First-Step Antihypertensive Treatment. Circulation Research 2019; 124(7):1113-1123 https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.313294

12. European Society of Cardiology. Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur Heart J 2019; doi/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455

13. Giugliano R P, Cannon CP, Blazing MA, et al. Benefit of adding ezetimibe to statin therapy on cardiovascular outcomes and safety in patients with versus without diabetes mellitus: results from IMPROVE-IT (Improved Reduction of Outcomes: Vytorin Efficacy International Trial). Circulation 2018;137(15):1571–1582. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030950

14. Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, et al, for the ODYSSEY OUTCOMES Committees and Investigators. Alirocumab and cardiovascular outcomes after acute coronary syndrome. New Engl J Med 2018;379(22):2097–2107. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1801174

15. Mega JL, Braunwald E, Wiviott SD, et al, for the ATLAS ACS 2–TIMI 51 Investigators (2012). Rivaroxaban in patients with a recent acute coronary syndrome. New Engl J Med 2012;366(1):9–19. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1112277

16. Eikelboom JW, Connolly SJ, Bosch J, et al, for the COMPASS Investigators. Rivaroxaban with or without Aspirin in Stable Cardiovascular Disease. New Engl J Med 2017;377(14):1319–1330. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1709118

17. Bonaca MP, Bhatt DL, Cohen M et al for the PEGASUS-TIMI 54 Steering Committee and Investigators. Long-Term Use of Ticagrelor in Patients with Prior Myocardial Infarction. New Engl J Med 2015; 372:1791-1800

18. Nordmann AJ, Nordmann A, Briel M, et al. Effects of Low-Carbohydrate vs Low-Fat Diets on Weight Loss and Cardiovascular Risk Factors: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Arch Intern Med 2006;166(3):285–293. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.3.285

19. Kuehn B. Evidence for HIIT Benefits in Cardiac Rehabilitation Grow Circulation 2019;140:514–515 https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042160

20. Public Health England. Health matters: stopping smoking – what works? 2019. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/health-matters-stopping-smoking-what-works/health-matters-stopping-smoking-what-works

21. Rapsomaniki E, Shah A, Perel P, et al. Prognostic models for stable coronary artery disease based on electronic health record cohort of 102 023 patients. Eur Heart J 2014;35(13):844–852. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht533