Cardiovascular assessment and examination for primary care nurses

Beverley Bostock

Beverley Bostock

RGN MSc MA QN

Advanced Nurse Practitioner Mann Cottage Surgery

Primary Care Nurse Coordinator Hereford

Practice Nurse 2021;51(9):30-34

Nurses in general practice are, increasingly, taking on extended roles, including seeing patients with undiagnosed symptoms. This, the first article in a series, looks at the assessment and examination of the cardiovascular system and explores the role of the Advanced Nurse Practitioner

Advanced Nurse Practitioners (ANPs) are an invaluable resource, for the NHS and patients alike. ANPs working in general practice, like others working at an advanced level, should comply with the standards set out by the Care Quality Commission (CQC) in line with the Core Capabilities Framework.1,2 This includes seeing people with undiagnosed symptoms, where the role of the ANP might involve taking a history, carrying out a physical examination, and ordering and interpreting tests in order to make a diagnosis.

According to the CQC, an ANP is a nurse with Level 7 (Masters) qualifications in clinical assessment, which includes history taking, physical examination and prescribing.1 The CQC says ANPs should be able to work in a first contact role to safely manage patients presenting with a range of symptoms, from the first presentation, through diagnosis and onto long-term management.1 Working in this way can deliver enhanced job satisfaction for the nurse as well as streamlining the patient experience, but it is important to ensure that adequate training, supervision and assessment of those working in this type of role has been completed before the ANP starts to work independently and autonomously.

In this article, we revisit the foundations of a robust cardiovascular assessment and examination, which aligns with the specific history and symptoms in order to support an evidence-based diagnosis and ensure the most effective intervention. This holistic approach to diagnosis and management should be implemented in order to optimise the diagnostic process.

HOW TO TAKE A ROBUST HISTORY

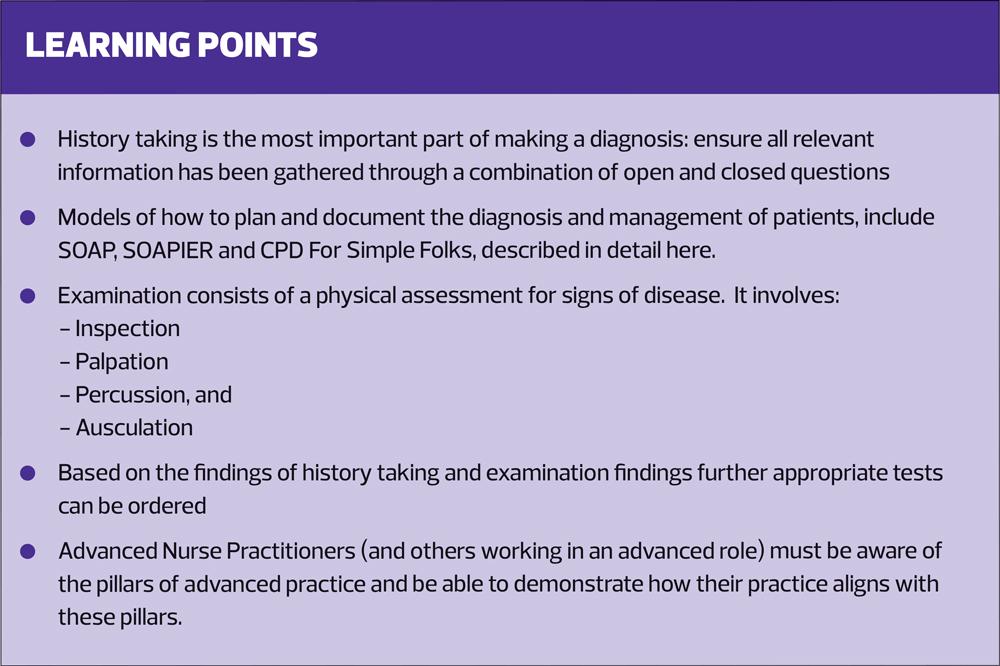

History taking is the most important part of making a diagnosis. Time should be spent on ensuring all relevant information has been gathered, using a combination of open and closed questions. History taking and physical examination will also inform decisions about which tests to order. A holistic view of the history, examination findings and test results will ensure that the diagnosis is made with care, based on a structured, methodical process.

Clinical negligence claims too often occur when a misdiagnosis, often as a result of poor diagnostic assessment, has caused harm, and yet little research has taken place to assess how diagnostic decisions are made in clinical settings.3 A process known as situational awareness, based on lessons learned from aviation, has been proposed as a way of improving the diagnostic process.4 Careful, structured and methodical history taking and documentation can act as the cornerstone to the diagnostic process.

Traditionally, there have been several models and examples of how to plan and document the diagnosis and management of patients, including SOAP:

- Subjective

- Objective

- Assessment

- Plan

and SOAPIER, with the addition of:

- Intervention

- Evaluation

- Revisions.5

CPD FOR SIMPLE FOLK

A model for history taking that I developed for myself when undertaking my Advanced Practice training was one that I named ‘CPD For Simple Folk’:

- Current presentation

- Past medical history

- Drug history (prescribed, over the counter and recreational, including alcohol and cigarettes)

- Family history

- Social history (housing, employment, relationships, environment, hobbies, mood and more)

- Feelings – based on the ICE model of ‘ideas, concerns and expectations’.6

A case history

Consider Sam’s history and current presentation, outlined in Box 1. Using CPD For Simple Folk, history taking reveals:

- Past medical history: includes type 2 diabetes (diagnosed 2 years ago) and hypertension (diagnosed 3 years ago). Sam also has osteoarthritis of the knees.

- Drug history: Sam takes metformin 2g daily, amlodipine 5mg and atorvastatin 20mg. He buys ibuprofen over the counter – he complains that the practice wouldn’t prescribe it for him. He smoked between the ages of 15 and 20 years of age and has a 4-pack year history. He drinks a couple of pints most evenings.

- Family history: Sam was adopted and knows nothing of his birth family.

- Social history: Sam is a retired policeman. He is divorced and lives with his cat in a ground floor retirement flat in the mining village where he grew up. He enjoys a game of golf and meets up with friends weekly to play, although it has been harder to complete a full 18 rounds lately, due to fatigue and breathlessness. He enjoys his life, overall, and has no past or current mental health issues.

- Feelings: Sam has some ideas, concerns and expectations about his health. He has friends who worked in the mines who have now been diagnosed with a range of respiratory conditions, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pneumoconiosis. He thinks he should have a chest X-ray and a breathing test.

Breathlessness can be caused by a range of conditions, including respiratory disease, heart conditions and metabolic or neurological abnormalities. However, Sam’s history offers some clues as to what the problem might be. His diabetes is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, heart failure and chronic kidney disease, all of which may be associated with dyspnoea.7 The fact that Sam reports nocturnal breathlessness suggests the possibility of orthopnoea or even paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea, both of which are associated with heart failure.8 Further questioning confirms the presence of orthopnoea, where lying flat causes a significant increase in breathlessness. In recent days Sam has been sleeping in an upright position on a tower of pillows. His ‘clear’ sputum is in fact frothy, once again suggesting a cardiac cause for his breathlessness.

KEY ELEMENTS OF A CARDIOVASCULAR EXAMINATION

Examination consists of a physical assessment for signs of disease. When documenting findings, it is important to include negative findings as well as positive ones, as this indicates that they have been evaluated.

Another aide memoire I used when training in advance practice was ‘Remember the HIPPO’ – History, Inspection, Palpation, Percussion and ‘Oscultation’ (i.e., auscultation as HIPPA was not as memorable!)

History

This should be taken methodically, as described above.

Inspection

This should include the patient’s facial expression, colour, gait and mobility, breathing, shape of the chest, jugular venous pressure (JVP), palm colour, finger clubbing, splinter haemorrhages, Osler’s nodes, capillary refill time, xanthomata or xanthelasma, corneal arcus, and scars.

Splinter haemorrhages and Osler’s nodes (tender lesions on the fingers and toes) are associated with a diagnosis of infective endocarditis, as are Janeway's lesions; painless, red, macular lesions situated on the palms and soles. Tidy advised that infective endocarditis is three times more common in men and that 25-50% of cases occur in the over-60s. It is also associated with other long-term conditions such as diabetes, cancer and alcohol abuse.9 This would be something to consider in Sam.

Palpation

This should include palpation of the radial, brachial, carotid and peripheral pulses, liver, evidence of peripheral or sacral oedema, heave or thrills.

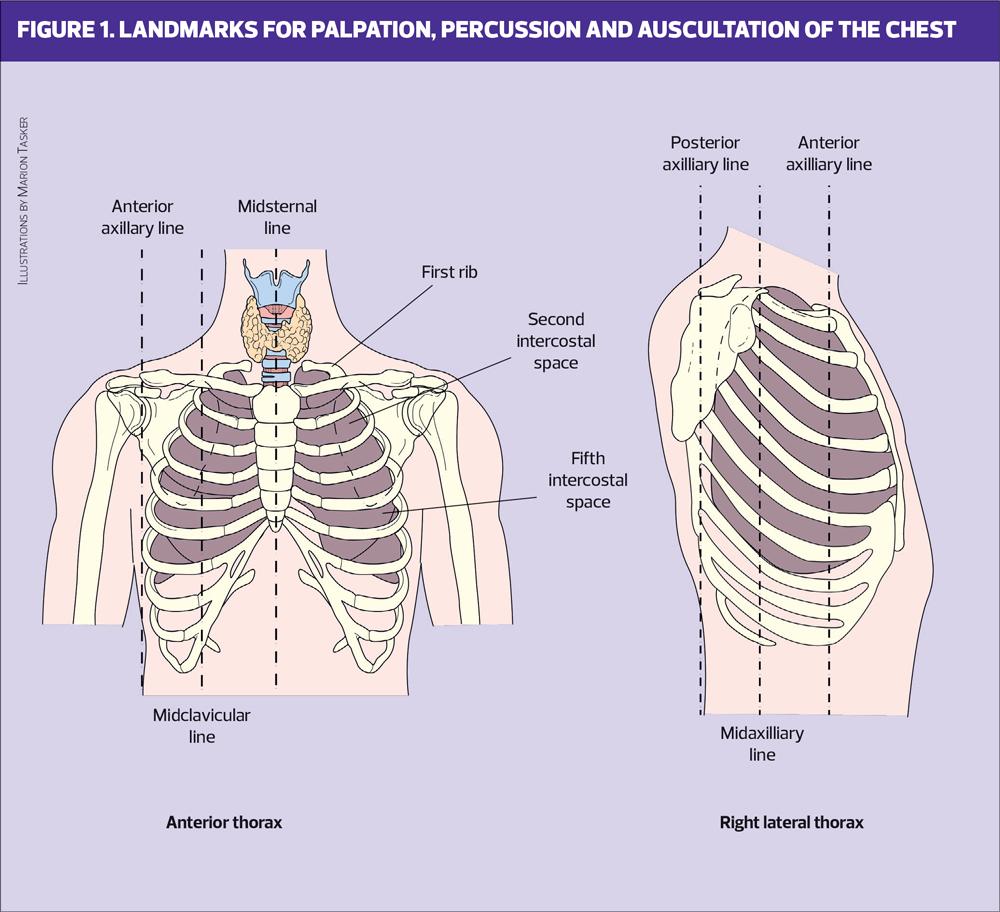

Radial pulses should be examined to detect the pulse rate and rhythm and to assess for radial-to-radial delay, suggestive of possible coarctation of the aorta.10 A collapsing pulse, which is identified by measuring the pulse in the normal and raised positions may be associated with atrial regurgitation.11 A heave indicates right ventricular hypertrophy and can be felt over the left parasternal region.10 (Fig 1) Thrills are palpable murmurs which, if present, can be felt over the site of the dysfunctional valve.10

Percussion

This will included the liver and lungs. Areas for percussion, palpation and auscultation, described here, are illustrated in Figure 1.

In heart failure the liver can become enlarged due to congestion. In order to assess the size of the liver (which should normally span 6-12cm at the midclavicular line) percussion starts at the 3rd intercostal space, midclavicular line. On moving down, a dullness on percussion will indicate the liver's upper border, which is usually at 5th intercostal space. Inferiorly, percussion starts below the umbilicus in the midclavicular line and moves up until dullness on percussion indicates the liver edge.12

The 5-7-9 rule can be employed when percussing the border of the liver. A normal sized liver should produce a dull percussion note from the 5th intercostal space in the midclavicular line, the 7th intercostal space in the midaxillary line and the 9th intercostal space in the scapular line. Any hyperresonance below these boundaries indicates possible lung hyperinflation, such as is seen in COPD, which may often co-exist with cardiovascular conditions.13

In cardiac disease, pulmonary oedema may be present, and both percussion and auscultation may help to identify it.

Auscultation

This is used to evaluate the position of the apex beat, whether heart and valve sounds are normal, and for the presence or absence of carotid bruits. Lung sounds should also be examined.

It is important to be confident and competent if listening to heart sounds. Normal heart sounds are documented as S1 and S2 and the presence of any extra sounds should alert the listener to assess possible causes, such as murmurs and valve disease. The position of the apex beat should be at the 5th intercostal space in the midclavicular line and any displacement should be noted and recorded.

Each valve should be located and auscultated – the mitral valve at the 5th intercostal space midclavicular line/left sternal border; the tricuspid valve at the 4th intercostal space, left lower sternal edge; the pulmonary valve at the 2nd intercostal space, left sternal edge and the atrial valve at the 2nd intercostal space, right sternal edge.14

In Sam’s case, the key findings were of a raised JVP, a third heart sound, peripheral oedema, hepatomegaly and bibasal crackles, all of which are in line with a diagnosis of heart failure, especially when taken together with his history.

INVESTIGATIONS AND MANAGEMENT

Based on the history and examination, appropriate tests can now be requested, including a full blood count, assessment of renal function, an updated HbA1c and lipid profile and an NT-pro-BNP test.8 The latter is a rule-out test for heart failure in that a normal result makes heart failure unlikely. Based on Sam’s presentation other tests are likely to be advised too, including an electrocardiogram and echocardiogram.8 Although some clinicians may decide to carry out lung function tests for breathlessness, the absence of risk factors for pulmonary disease makes these less of a priority.

Sam had a raised NT-pro-BNP and was fast-tracked into a community heart failure clinic where an echocardiogram confirmed the presence of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Having been prescribed a diuretic for his symptoms, he then started on treatment to improve his morbidity and mortality, including an ACE inhibitor (eventually moving onto sacubitril/

valsartan), a beta blocker and dapagliflozin.8 His ongoing management was jointly supervised by the ANP in general practice and the community-based heart failure specialist nurse.

WHERE TO ACCESS FURTHER INFORMATION

Increasingly, primary care clinicians can access advice and guidance from consultants prior to referral into hospital. Pathways may be in place to support primary care clinicians to refer appropriately in their geographical area, and there may also be community clinics (hubs) staffed by clinicians with a special interest in the condition where patients suspected of having a particular diagnosis can be seen.

The publication of the updated guidance on primary care services from 2022-23 includes recommendations about having a cardiovascular disease lead for each primary care network and also highlights the role of primary care in the early diagnosis and management of heart failure.15 Public Health England has also reiterated its commitment to detect and protect people with undiagnosed cardiovascular risk factors and perfect the management of atrial fibrillation, hypertension and dyslipidaemia.16

HOW TO COMPLY WITH GUIDANCE ON THE ROLE OF THE ANP

ANPs (and others working in an advanced role) should be aware of the pillars of advanced practice and be able to demonstrate how their practice aligns with these pillars. The CQC, the Royal College of Nursing and the Royal College of General Practitioners have all published on the topic of ANPs.1,2,17 It is essential that people working as an advanced practitioner can demonstrate their credentials, especially if possible clinical negligence is reported.

When seeing people with undifferentiated symptoms, such as Sam, ANPs should be competent in taking a full history, carrying out a physical assessment, ordering and interpreting tests, making a diagnosis and planning ongoing treatment and management. If there are any areas where they lack confidence and competence, they should refer on to a colleague who has the relevant competencies, but should also use this as an opportunity to reflect and learn.

SUMMARY

Cardiovascular disease is a priority for the NHS and this has been highlighted in several recent publications. Primary care clinicians should be aware of the possibility of a cardiovascular problem in people presenting with a range of symptoms. In the case study presented here, the key symptom was breathlessness, which has many potential causes. However, through a careful process of robust history taking, physical assessment and tests, the diagnosis of heart failure was made and appropriate management and follow up instigated. ANPs are increasingly involved in the diagnosis of undifferentiated illness and can be competent to do so, in line with national guidance on ANP competencies.

REFERENCES

1. Care Quality Commission. Advanced Nurse Practitioners (ANPs) in primary care. 2021 https://www.cqc.org.uk/

guidance-providers/gps/gp-mythbuster-66-advanced-nurse-practitioners-anps-primary-care

2. Royal College of General Practitioners/Skills For Health. Core Capabilities Framework for Advanced Clinical Practice (Nurses) Working in General Practice / Primary Care in England. 2020 www.skillsforhealth.org.uk/images/services/

cstf/ACP%20Primary%20Care%20Nurse%20Fwk%202020.pdf

3. Singh H, Petersen L A, Thomas E J. (2006). Understanding diagnostic errors in medicine: a lesson from aviation. BMJ Quality & safety 2006; 15(3): 159–164. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.2005.016444

4. Singh H, Giardina T D, Petersen L A, et al. Exploring situational awareness in diagnostic errors in primary care. BMJ Quality & Safety 2012; 21(1): 30–38. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000310

5. Lenert LA. (2017). Toward medical documentation that enhances situational awareness learning. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2016; 2016: 763–771. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5333306/

6. Matthys J, Elwyn G, Van Nuland M, et al. (2009). Patients' ideas, concerns, and expectations (ICE) in general practice: impact on prescribing. BJGP 2009; 59(558): 29–36. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp09X394833

7. Low Wang CC, Hess CN, Hiatt WR, et al. (2016). Clinical Update: Cardiovascular Disease in Diabetes Mellitus: Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease and Heart Failure in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus - Mechanisms, Management, and Clinical Considerations. Circulation 2016; 133(24): 2459–2502. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022194

8. NICE NG106. Chronic heart failure in adults: diagnosis and management; 2018 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng106

9. Tidy C. Infective Endocarditis; 2015. https://patient.info/doctor/infective-endocarditis-pro

10. Ashley EA, Niebauer J. Cardiology Explained; 2004. London: Remedica Chapter 2, Cardiovascular examination. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2213/

11. Geeky Medics. Cardiovascular Examination. 2017 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XU_xeUMJ3Zc

12. Wolf DC. Evaluation of the Size, Shape, and Consistency of the Liver. In: Walker HK, Hall WD, Hurst JW, editors. Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 1990. 3rd edition. Boston: Butterworths Chapter 94. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK421/

13. Stanford Medicine. Pulmonary Exam: Percussion and Inspection; 2016 https://stanfordmedicine25.stanford.edu/

the25/pulmonary.html

14. Tidy C. Heart Auscultation. 2015 https://patient.info/doctor/heart-auscultation

15. NHS England. Primary Care Networks – plans for 2021/22 and 2022/23; 2021 https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/primary-care-networks-plans-for-2021-22-and-2022-23/

16. Waterall J. The 10-year CVD ambitions for England – one year on; 2020. https://publichealthmatters.blog.gov.uk/

2020/02/06/the-10-year-cvd-ambitions-for-england-one-year-on/

17. Royal College of Nursing. RCN Standards for Advanced Level Nursing Practice; 2018 https://www.rcn.org.uk/professional-development/publications/pub-007038