Malignant melanoma:what happens after diagnosis

Dr Ed Warren

Dr Ed Warren

FRCGP, FAcadMEd

Primary care can be involved at every stage of the patient’s cancer ‘journey’, from the initial suspicion of malignancy to survival. Using melanoma as an example, we look at what happens along the cancer pathway

The way that the NHS deals with cancer falls into roughly four phases (if you don’t count the patient’s decision to see someone about a worrying symptom). At first contact with primary care, an assessment will be made to see if there might be a cancer. Our patients are scared of ‘the Big C’, even though the outlook for other illnesses can be worse than for many cancers, and for the Government, performance in the international cancer ‘league tables’ is an important consideration. So there are political as well as clinical reasons to take cancer seriously.

A whole set of clinical rules exists just to get possible cancer into the NHS system. In 2015, the second version of NICE’s Referral guidelines for suspected cancer was produced,1 and the bar was lowered so that the 2015 guidelines suggest referral if the cancer risk is 3% or above, whereas the previous 2005 guidelines used a 5% threshold.2 Once a significant risk is determined, then there is the ‘Two Week Wait’ pathway through which a patient with possible cancer has to be seen in secondary care within 2 weeks. Two weeks may sound like rapid access, but some of our patients feel that all referrals to secondary care should be seen within 2 weeks, and they may have a point.

Secondly, all hell breaks loose. Appointments are made by telephone, investigations are arranged, and all the stops are pulled out to find out what is going on. Being investigated for possible cancer is a full-time job for patients, with all the blood tests, scans and appointments that are involved. Things run at a mile a minute, and if your patient didn’t already feel nervous, all the frenzied activity will have generated a state of anxiety. But keep in mind that in a vast majority of cases, your patient will not have cancer: there is a 97% chance of a non-cancer diagnosis. Some years ago, I did an audit in my practice of ‘Two Week Wait’ referrals for suspected melanoma, and over a full year not a single one turned out to be cancer.

Thirdly, if a cancer is confirmed, a treatment plan is implemented. This is where things get a bit technical: not only is cancer care a highly specialised area, it also changes very quickly as new treatments become available so that it is almost impossible to stay up to date. Also, many cancer centres appear to be running trials all the time, so your patient may be enrolled for a novel treatment that you have not even heard of.

And fourthly, nearly all patients survive cancer in the sense that they have many years of life after diagnosis. This ‘survivorship’ phase is the fate of a large number of our patients, and it brings with it several care needs.3

Primary care may be involved at any or all of these stages. Even when your patient’s care is in the hands of specialists, your patient may turn to you for advice and information. Many cancer care units have specialist nurses to help patients through the care pathway, but these are new people and not familiar to your patients. They also serve a specialised function and so may not have a full grasp of your patient’s holistic needs. And sometimes it seems to patients that the specialist doctors who work in secondary care are motivated by interest in the specialty rather than an interest in being able to communicate with their patients. Sorting out communication failures with patients is a common task for most general practice nurses.

PHASE ONE: SUSPECTING THE DIAGNOSIS

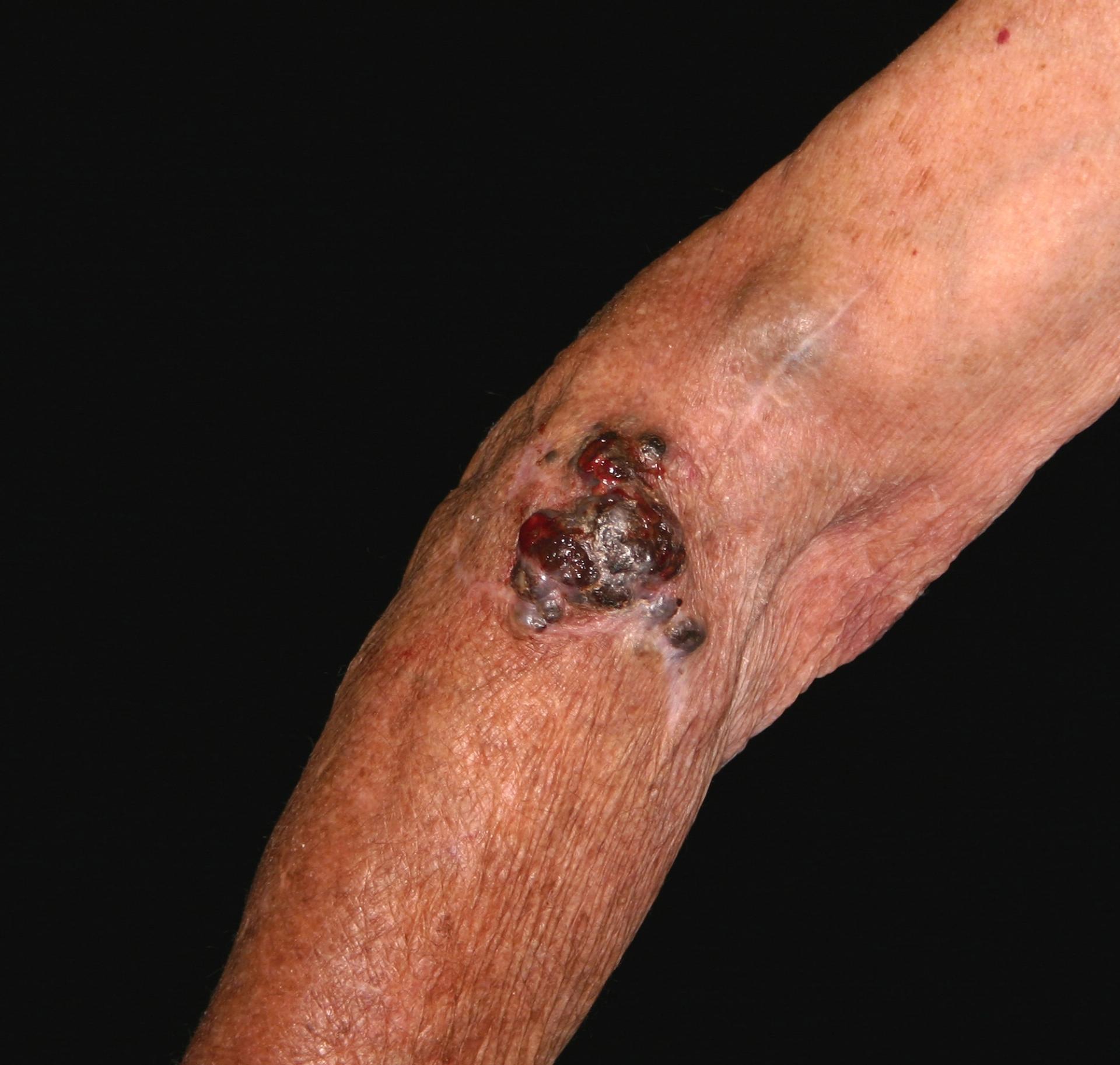

In the case of melanoma, this phase is relatively easy because melanoma has received a lot of attention over the last 40 years, as the increase in foreign package holidays has contributed to an increase in incidence: all types of skin cancer are related to sun exposure, and uniquely, malignant melanoma appears related to episodes of sunburn.4 The process starts when a patient presents to primary care with a mole that they are concerned about.

NICE Clinical Knowledge Summaries (CKS) currently recommend the use of a 7-point checklist (Box 1). A major feature scores 2 points and a minor feature scores 1 point. Anyone with a score of 3 or more should be referred under the ‘Two Week Wait’ protocol, usually to a dermatologist.5 There is a proviso, however, that in situations of high suspicion even one major or minor feature should prompt referral – an obvious example would be when there has been a previous diagnosis of malignant melanoma. The checklist can also be used to reassure patients who probably do not have malignant melanoma.

Moles are not common at birth, and usually develop in the second and third decades of life, so that by 30 most fair-skinned people will have 20 to 30 moles. These developments are natural, and do not infer the development of a melanoma. Moles can also develop in early childhood (2 – 10 years) and are usually related to sun exposure. However, a new mole that appears after puberty should be regarded with suspicion.6

PHASE TWO: MAKING THE DIAGNOSIS

Rarely a mole removed by a minor surgery procedure in primary care will, on histological examination, unexpectedly turn out to be a malignant melanoma (NICE does not recommended that suspected melanomas are routinely removed in primary care). In such cases, a diagnosis can be made straight away, but even so an urgent specialist referral will be made for confirmation and further treatment. More commonly a patient will present with a mole that they are concerned about, and this will prompt the referral.

The British Association of Dermatologists (BAD) produced revised guidance in 2010 about the management of melanoma.6 (This was due to be updated in 2015, but a further revision has yet to be published.)

At the hospital clinic, there will be an examination of your entire patient’s skin, not just the suspicious mole. People with a melanoma are more at risk of having another melanoma, and they may occur on less visible bits of skin, so it makes sense to do a comprehensive inspection. A dermatoscope may be used for this – a piece of equipment that looks like a magnifying glass or camera with a light. The dermatoscope will have a magnifying glass to see the lesion better (typically with a 10X magnification). Also there will be some method of reducing reflection from the skin – older versions used a liquid medium, but newer models overcome this problem by using a polarised light source. A photograph of the mole may be taken.

Particular attention will also be paid to any lymph node swelling. If a melanoma has spread, then the lymph nodes are usually affected first. Swelling of lymph nodes near the melanoma is one way of checking whether or not the melanoma is likely to have metastasised.

Next, arrangements will be made for the entire mole to be excised. Together with the mole, a cuff of skin that looks normal will also be removed with at least a 2mm margin, and also some underlying skin fat. This way the thickness of the mole can be determined, which is important for future treatment. The excised tissue is sent to the laboratory to be examined in detail. The wound is sutured.

Getting the results from the laboratory will take at least a few anxious days. A lot is riding on the results. In most cases, it will not be cancer at all. But if it is cancer, the laboratory results will confirm its thickness, the type of melanoma it is, and whether there are any signs that it might have spread: all these factors have a bearing on the sort of treatment that might be necessary.

At this point it will be possible to ‘stage’ the melanoma, to confirm what if anything more will need to be done. Full details can be found in the Revised U.K. guidelines for the management of cutaneous melanoma.6 The staging process requires knowledge of whether the cancer has spread, and your patient may be offered a sentinal node biopsy: dye is injected into the melanoma to determine which lymph nodes drain the region of the melanoma, and then the nodes are excised under a general anaesthetic and sent for analysis. Another option is to perform an ultrasound scan, and then a needle biopsy of any suspicious lymph nodes. Having the proper biopsy might seem to be the better choice, but currently it is not clear that having a biopsy alters prognosis.7

Staging

- Stage I has two subdivisions (A & B): these are the thin lesions with no sign of spread. (The thickness of a melanoma is called the Breslow Thickness, named after Alexander Breslow at George Washington University USA in 1970).

- Stage II has three subdivisions (A to C). These melanomas can be up to 4mm thick, but there are no signs of spread.

- Stage III also has three subdivisions. These are the melanomas where there is evidence of microscopic spread, or (in the more severe subdivisions) evidence of lymph node involvement and swelling.

- Stage IV has three subdivisions. There is evidence of distant spread of secondaries, either to skin, lung or elsewhere. This is not good news.

Stages III and above suggest that the melanoma has spread, and your patient could well be offered a detailed scan – CT, MRI or PET – to find out where to and by how much this spread has occurred. On the Cancer Research UK website, there is a page on Further tests for melanoma that includes useful information, aimed at patients, about what each of these scans involves.7

Genetic testing may be done on the tumour biopsy. Around half of those diagnosed with melanoma carry a gene called BRAF V600. Patients who carry this gene will require different treatment.

It is recommended that disclosure of a diagnosis of melanoma should be made or overseen by a doctor who has received advanced communication skills training.6 Giving bad news is certainly a serious business and should be done properly. However, every time a diagnosis of disease is made this probably represents ‘bad news’ for your patient, and so it is odd that the advanced communication skills training should be reserved for the most serious skin cancer. Sensibly, it is also recommended that a skin cancer trained nurse should be at hand to offer support.

PHASE THREE: TREATMENT

In the pursuit of obtaining ‘informed consent’, clinicians may fall into the trap of bombarding their patients with statistics and then asking them what they want to do. This is a cop-out. Your professional responsibilities cannot be absolved in such a crude manner. Most patients will not be able to deal with this deluge of unfamiliar information, particularly shortly after being told they have cancer, and will probably turn to their GPN for advice. ‘What would you do?’ is of course an impossible question to answer, but it is often possible to tailor your advice by finding out your patient’s beliefs and priorities. Some patients are prepared to subject themselves to all manner of privations in search of a cure for their cancer. Others will not wish any degree of iatrogenic discomfort. Yet others will want to deny that any of this is happening to them, and want nothing to do with doctors and hospitals and treatment.

Other than surgical excision there does not appear to be any cure for melanoma,6 but that does not mean that other treatments have not been tried and studied, and that some people in some situations may secure temporary relief even if they do not live any longer. Also, trials are going on all the time, and BAD suggest that if a trial is available, then you should encourage your patient to go on it.6 Perhaps one day something useful will emerge.

As well as excision of the primary lesion, surgery may be suggested to deal with any new lesions or any secondaries. Also surgery is sometimes suggested in a palliative role, for instance if the melanoma has caused spinal cord compression.

Chemotherapy in the form of dacarbazine may be suggested if there has been metastatic spread: it does not cure the cancer, but may give some palliative relief.6 It is an injection and can be given regionally, meaning that only the body site containing the melanoma is infused with drug. Side effects are allegedly rare but include local irritation of the skin; bone marrow suppression; nausea and vomiting; and hair loss.8

For patients who have metastases and are BRAF V600 positive, a further option is vemurafenib. This is a tablet so can be taken at home. A plethora of side effects is listed in the Summary of Product Characteristics, and they are common. They include headache, diarrhoea, vomiting, joint pains, hair loss, and more rarely, a syndrome called DRESS (Drug Rash with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms), which can be fatal.8

If the melanoma is very thin, and if surgical removal would be disfiguring, then imiquimod cream may be recommended.9 It is not licensed for the treatment of melanoma – its license is for genital warts – but can be prescribed off-license, after careful discussion which should be recorded in the patient’s notes. Imiquimod may cause local burning and muscle pains, and can also cause hair loss.

Radiotherapy may be advised, but only for reasons of palliation.6

Some patients will feel abandoned when the period of diagnostic tests and treatment is concluded. They go from being the focus of energetic attention to the occasional clinic visit. This may have psychological implications that may well lead your patient to turn to primary care and the GPN.

Follow-up

After the treatment is all over, what next? Some sort of follow-up will be arranged, to detect recurrence, to look for new primary melanomas, and to offer information and reassurance. No-one is sure what the optimum regime of follow-up is.6 In 62% of cases where there is recurrence it is the patient who finds it, rather than a specialist at a formal review. If there is recurrence it is most likely in the first 5 years, but that is not to say that there are no recurrences after this time. Patient opinion is divided about whether they find routine reviews reassuring, or whether they just provoke extra anxiety.6

For the very thinnest of melanomas, there is no risk of metastasis. So once the lesion has been completely excised, a single follow-up hospital visit is all that is required, to offer information, check the skin and to teach self-examination.

For the IA melanomas (less than 1mm thick and no ulceration), two-to-four clinic visits over 12 months are recommended. After this, as long as all is well, your patient will be discharged.

The greatest risk of recurrence for IB melanoma (less than 2mm thick or 1mm if there is ulceration) up to IIC (less than 4mm thick with ulceration) occurs in years 2 to 4 after diagnosis. So checks every 3 months for 3 years, and then every 6 months for a further 2 years, making 5 years in all are recommended.

If there has been a sentinel node biopsy that has proved positive, this will be followed-up with an excision of all the involved nodes, and confirms at least IIIA disease. The outlook will depend on how many lymph nodes are involved. Evidence is clearly lacking for appropriate surveillance intervals.6

Stage IIIB and above (there is confirmation of metastases) will be under the care of a specialist skin cancer multidisciplinary team, and follow-up will be variable depending on need. It is suggested that an appropriate plan would be for a clinic visit every 3 months for 3 years, then 6 monthly for 2 years, then annually for 5 years – making 10 years in all.

Prognosis

Melanoma UK10 offers the following figures. These are expressed in terms of 5-year survival – what are my chances of being alive in 5 years time? This accepts the reality that, except in the mildest disease, there is a risk of recurrence or spread for the rest of your patient’s life, but that the risk of this happening reduces with time. Also, more of your patient’s skin than just the melanoma will have been exposed to the same risks – sun exposure, genetic predisposition – so the chance of a second melanoma is higher.

For melanomas in general, after diagnosis in the UK, 86% of patients will be alive after 5 years and 83% at 10 years. Early stage disease is detected much more commonly than more advanced disease. Prognosis gets worse according to stage, with 5-year survival as follows:

- Stage I - 90%

- Stage II - 80%

- Stage III - 40% to 50%

- Stage IV - 20% to 30%

PHASE FOUR: LIFE WITH CANCER

According to Macmillan Cancer Support there are 2.5 million people in the UK who are living with a diagnosis of cancer.11 That means that for an average general practice of 8,000 patients there will be about 350 people living with cancer. Add to this number their friends and relatives, and quite a sizeable proportion of the practice list is affected. Many of the patients will be elderly (nearly all cancers become more common with advancing age) and so may well have other health problems as well as the cancer. In your role as GPN your future work will be increasingly involved with this group – Cancer Survivors. How can you help? Find out next time.

REFERENCES

1. NICE. Referral guidelines for suspected cancer. [NG12] June 2015

https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG12/chapter/1-Recommendations-organised-by-site-of-cancer [Accessed 7.8.16]

2. NICE. Referral guidelines for suspected cancer. [CG27] June 2005. This guideline has been withdrawn.

3. Macmillan. Survivorship. http://www.macmillan.org.uk/aboutus/healthandsocialcareprofessionals/macmillansprogrammesandservices/survivorship.aspx [Accessed 7.8.16]

4. Taylor A and Gore M. Melanoma: detection and management. Update 1994;48:209-219.

5. NICE/CKS. Melanoma and pigmented lesions. http://cks.nice.org.uk/melanoma-and-pigmented-lesions [Accessed 8.8.16]

6. Marsden JR et al. Revised U.K. guidelines for the management of cutaneous

melanoma 2010. British Journal of Dermatology 2010 163, pp238–256

7. Cancer Research UK. Further tests for melanoma. http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/type/melanoma/diagnosis/further-tests-for-melanoma [Accessed 8.8.16]

8. British National Formulary. www.BNF.org [accessed 8.8.16]

9. NICE. Melanoma: assessment and management. [NG14]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng14/chapter/1-Recommendations#managing-stages-0ii-melanoma [Accessed 8.8.16]

10. Melanoma UK. Statistics. http://www.melanomauk.org.uk/about_melanoma/statistics/ [Accessed 22.8.16]

11. Macmillan Cancer Support. Statistics Fact Sheet. http://www.macmillan.org.uk/documents/aboutus/research/keystats/statisticsfactsheet.pdf [Accessed 10.8.16]