Time to consign SABA-only treatment for asthma to history books

Beverley Bostock

Beverley Bostock

RGN MSc MA QN

Nurse Practitioner Mann Cottage Surgery, Moreton in Marsh

PCN Nurse Coordinator Hereford

Primary Care Cardiovascular Society Committee Member

Mandy Galloway

Editor

Practice Nurse 2021;51(10):16-20

It is over two years since publication of the most recent British Asthma Guideline, and even longer since NICE published its guidance - so if we want to base practice on the most up-to-date evidence, we need to look further afield

In 1999 the British Thoracic Society (BTS) and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) agreed to jointly produce a comprehensive new asthma guideline, both having previously published guidance on asthma. The original BTS guideline dated back to 1990 and the SIGN guidelines to 1996. Both organisations recognised the need to develop the new guideline using evidence based methodology.1

The joint process was further strengthened by collaboration with Asthma UK, the Royal College of Physicians of London, the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, the General Practice Airways Group (now Primary Care Respiratory Society UK), and the British Association of Accident and Emergency Medicine (now the College of Emergency Medicine).

The outcome of these efforts was the British Guideline on the Management of Asthma, developed using SIGN methodology and first published in 2003.

Since then, sections of the guideline have been updated annually until 2014, then biennially from 2014, with the most recent version published in 2019.

But in the meantime, NICE also published a guideline on asthma – NG80, in 2017.2 And in a number of areas its recommendations differed from those in the well-established and respected British Guideline. It was therefore agreed in 2019 that the three organisations would produce a single, joint, UK-wide guideline to support healthcare professionals in making accurate diagnoses and provide effective treatments, and to include recommendations covering areas where differences had previously existed between the guidelines.3

Only a couple of months back, the author of the Practice Nurse article on paediatric asthma4 wrote: ‘The difference in guidelines is frustrating for health professionals in front line clinical practice… and publication of joint BTS/SIGN and NICE national asthma guidelines is eagerly awaited.’

However, our author – along with everyone else – is in for a long wait. Recruitment to the guideline development committee only began on 30 September 2021, and while NICE says the publication date is TBC, people in the know say it is unlikely before 2024.

That makes UK guidance, at best, out of date. So if general practice nurses want to ensure their practice reflects the most recent evidence, they should turn to the Global Initiative for Asthma guideline, released in November 2021.5

GINA 2021 REPORT

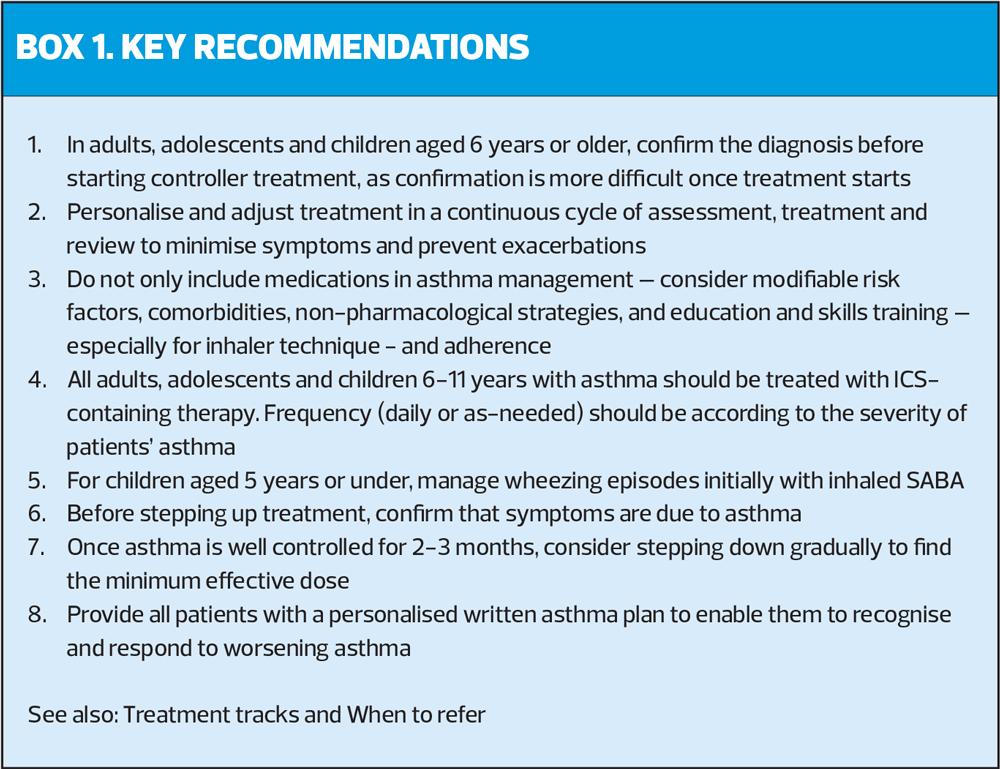

The GINA 2021 report reinforces the key message that no one, aged 6 years and over, should have their asthma managed with a short acting beta2 agonist (SABA) alone – and that everyone aged 5 years and over, with confirmed asthma, should receive inhaled corticosteroids (ICS).5

This decision was based on evidence that SABA-only treatment increases the risk of severe exacerbations, and that adding an ICS significantly reduces this risk. The ICS-containing treatment can be delivered by regular daily treatment, or in mild asthma, by as-needed low dose ICS-formoterol. In the UK, however, this approach would involve the use of unlicensed medication as no combination inhaler is licensed to use on a purely ‘as required’ basis.

GINA points out that even patients with apparently mild asthma are still at risk of serious adverse events, in that:

- 30-37% of adults with acute asthma

- 16% of patients with near-fatal asthma, and

- 15-20% of adults dying of asthma

…had symptoms less than weekly in the previous 3 months.6

Inhaled SABA had previously been first-line treatment for asthma for 50 years, dating back to the era when asthma was thought to be a disease of bronchoconstriction. Its role has been reinforced by its rapid relief of symptoms, and because it is cheap. But starting patients on SABA trains them to see it (and potentially rely on it) as their primary asthma treatment.

Evidence dating back more than a decade shows that regular use of SABA, even for just a couple of weeks, is associated with adverse effects, from β-receptor downregulation, decreased responsiveness, rebound hyperesponsiveness, and increased allergic response and easinophilic airway inflammation.7,8

Since the National Review of Asthma Deaths (NRAD) report came out in 2015,8 which recommended that patients should not be prescribed more than 12 short-acting reliever inhalers in a year (without an urgent review), some progress has been made in reducing prescribing of SABA – but it is still estimated that more than eight out of 10 SABA inhalers are prescribed to patients who are potentially over-using them.9 Furthermore, most clinicians would agree that using more than six SABA inhalers per year is significant, when good control should mean that patient requires no more than two relievers (400 doses) in a year.

GINA explicitly warns that prescribing three or more SABA inhalers per year (i.e daily use) is associated with a high risk of severe exacerbations, and 12 or more per year is associated with a much higher risk of death.

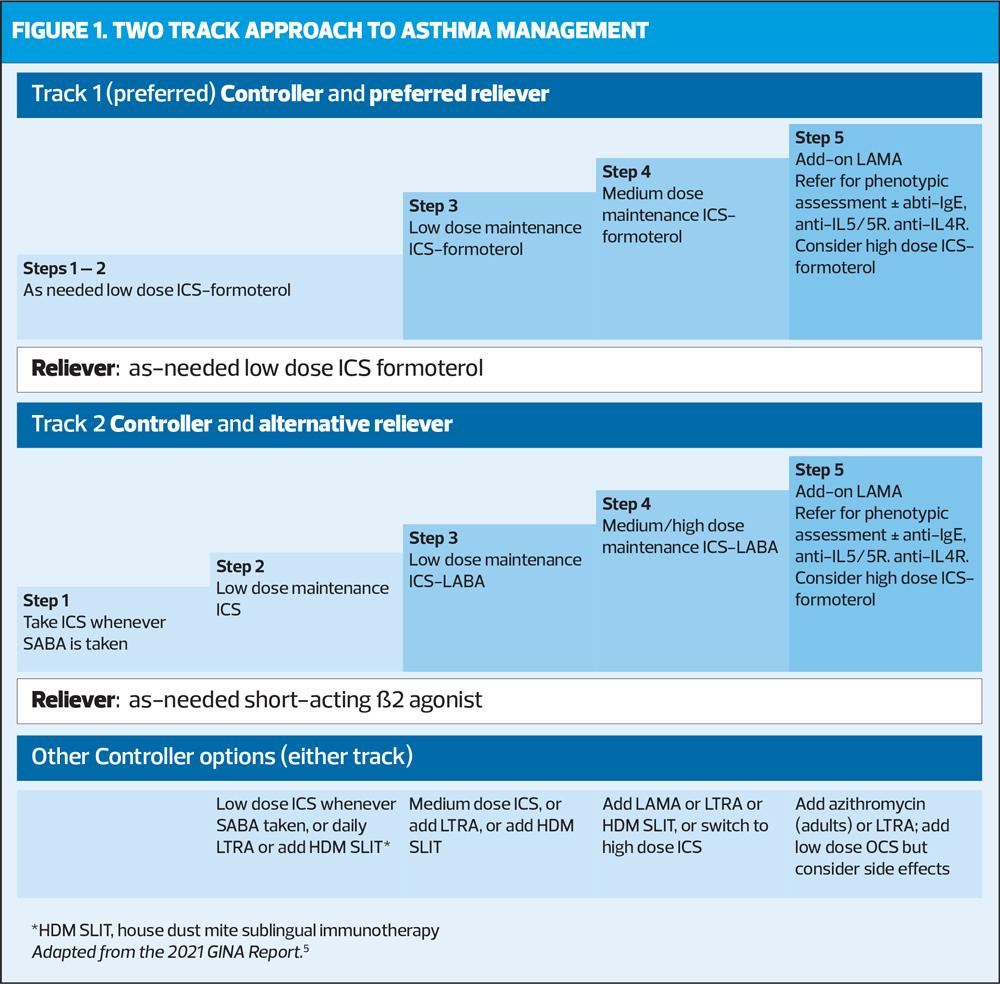

GINA therefore recommends a two-track approach (Figure 1): Track 1, with low dose ICS-formoterol (a long acting beta2 agonist [LABA]) as the reliever, is GINA’s preferred approach: it reduces the risk of exacerbations compared with using a SABA reliever, with similar symptom control and lung function.

With Track 1, when a patient at any treatment step has asthma symptoms, they use low dose ICS-formoterol (in a combination inhaler) for symptom relief. In steps 3-5, patients also take ICS-formoterol as their daily controller treatment (maintenance and reliever therapy [MART]). Note that ICS-formoterol should not be used as the reliever in patients prescribed a different ICS-LABA for their controller therapy.

If Track 1 is not possible, or is not preferred by a patient with no exacerbations on their current controller therapy, Track 2, with SABA as the reliever is an alternative approach. But before offering a regimen with SABA, consider whether the patient is likely to be adherent with daily controller – if not, they will be exposed to the risks of SABA-only treatment.

In all patients, GINA recommends that we should offer a continuous cycle of assessment, adjustment and review. This should comprise:

Assess

- Confirmation of the diagnosis if necessary

- Symptom control and modifiable risk factors (including lung function)

- Comorbidities

- Inhaler technique and adherence

- Patient preferences and goals

Adjust

- Treatment of modifiable risk factors and comorbidities

- Non-pharmacological strategies

- Asthma medications (adjust down/up/between tracks)

- Education and skills training

Review

- Symptoms

- Exacerbations

- Side-effects

- Lung function

- Patient satisfaction

WHY TRACK 1 IS PREFERRED

Severe exacerbations can occur, even in ‘mild’ asthma, and are often the unpredictable consequences of viral infections, allergen exposure, air pollution and stress. ICS is highly effective in mild asthma, but patients are often poorly adherent – perhaps because there is no immediate relief of symptoms as there is with SABA. The episodic nature of asthma can lead to patients discontinuing their medication when they feel well, and starting it again if symptoms become more pronounced or they experience an exacerbation. However, this often takes the form of overuse of reliever inhalers and ‘as-needed’ use of maintenance medication.10

There is no evidence for the safety or efficacy of SABA-only treatment – on the other hand, there is evidence – albeit indirect – for the safety and efficacy of as-needed ICS-formoterol. There is no difference in risk reduction for exacerbations with ICS or ICS-formoterol assessed by symptom frequency, and even a single day of higher ICS-formoterol use reduces the risk of progression to needing OCS.11

Even occasional courses of OCS increase the risk of serious adverse outcomes, such as osteoporosis, diabetes and cataract.12

WHAT IS MILD ASTHMA?

Given that patients with so-called intermittent asthma are still at risk of severe exacerbations, is there even such a thing as ‘mild’ asthma? GINA is planning to review the definition of mild asthma, but it is currently defined as asthma that is able to be well-controlled with reliever alone or low dose ICS. (GINA recommends that severity is assessed retrospectively, after 2-3 months of treatment, from the level of treatment required to control symptoms and exacerbations.)

In research studies, mild asthma is often defined by treatment with SABA alone, or low dose ICS – but patients may be being under- or over-treated.5 Patients and clinicians would tend to consider mild asthma to mean infrequent or mild symptoms.

GINA does not distinguish between intermittent and mild persistent asthma – historically this was an arbitrary distinction, based on an assumption that patients with symptoms less than twice a week would not benefit from ICS, when we now know that such patients are still at risk of severe exacerbations, and this risk is reduced by ICS-containing treatment.

And severe asthma?

GINA has updated its definition of severe asthma to remove reference to GINA treatment steps, because these have changed over the years. It is now defined as: ‘Asthma that remains uncontrolled despite optimised treatment with high dose ICS-LABA, or that requires high dose ICS-LABA to prevent it from becoming uncontrolled.’

Step 5 recommendations for add-on LAMA have been updated to include combination triple therapy, i.e. ICS-LABA-LAMA, if asthma is persistently uncontrolled despite ICS-LABA. Triple combinations suitable for patients aged 18 and over include beclometasone-formoterol-glycopyrronium (Trimbow®); fluticasone furoate-vilanterol-umeclidinium (Trelegy Ellipta® – although this product is not currently licensed for asthma in the UK); and mometasone-indacaterol-glycopyrronium (Enerzair® Breezhaler®). For children aged 6 years and above, a suitable add-on would be tiotropium (Spiriva® Respimat®), in a separate inhaler.

ASTHMA IN CHILDREN (6-11 YEARS)

GINA’s preferred treatment pathway for children aged 6-11 years with a confirmed diagnosis of asthma, with symptoms less than twice a month, is to start with low dose ICS whenever SABA is taken (Step 1) to prevent exacerbations and control symptoms. For those who have symptoms more than twice a month, but less than every day, a daily low dose ICS is recommended (Step 2).

If the child has symptoms most days, or is waking with asthma once a week or more, a move up to Step 3 – low dose ICS-LABA, or medium dose ICS, or very low dose ICS-formoterol MART – would be indicated. However, the only ICS/formoterol combination licensed for children in the UK is Symbicort® and this is only licensed from age 12.

Children with symptoms most days, waking with asthma once a week or more, and low lung function will need to be stepped up to medium dose ICS-LABA, or low dose ICS-formoterol MART (see above regarding licensing), AND referred for expert advice. Short courses of OCS may also be needed for patients presenting with severely uncontrolled asthma, but this too would be a red flag for referral.

At Step 5, when the child would be under specialist care, phenotypic assessment should be carried out, plus or minus higher dose ICS-LABA or add-on therapy, e.g. biologic therapy such as anti-IgE.

An alternative approach would be to consider a low dose ICS + as-needed SABA (or ICS-formoterol reliever for MART as above) at Step 1, then adding a daily leukotriene receptor antagonist (LTRA), or low dose ICS whenever SABA is taken (Step 2). Step 3 would be to use low dose ICS + LTRA. If these measures do not control symptoms, refer for expert advice.

The advice for children 5 years old or under, is to consider as-needed SABA, but only if the child has infrequent viral wheezing or few interval symptoms.

- If their symptom pattern is not consistent with asthma but wheezing episodes requiring SABA occur frequently, e.g. ≥3 per year, OR

- Their symptom pattern is consistent with asthma but their symptoms are not well-controlled or they are having ≥3 exacerbations a year…

…offer a diagnostic trial of daily low dose ICS for 3 months, or alternatively, daily LTRA or intermittent short courses of ICS at the onset of a respiratory illness. Consider referring to a specialist.

This recommendation contrasts with the current BTS/SIGN guidance, and clinicians need to consider the advantages and disadvantages of each guideline before consulting with parents about their preferred course of action. Careful documentation of the decision-making process is essential.

For children aged ≥5 years with a confirmed diagnosis of asthma, whose asthma is not well controlled on low dose ICS, consider a doubling the low dose ICS (or continue low dose ICS and add LTRA). As in any case of uncontrolled asthma, before stepping up, check for alternative diagnosis, check inhaler skills, review adherence and exposure to triggers.

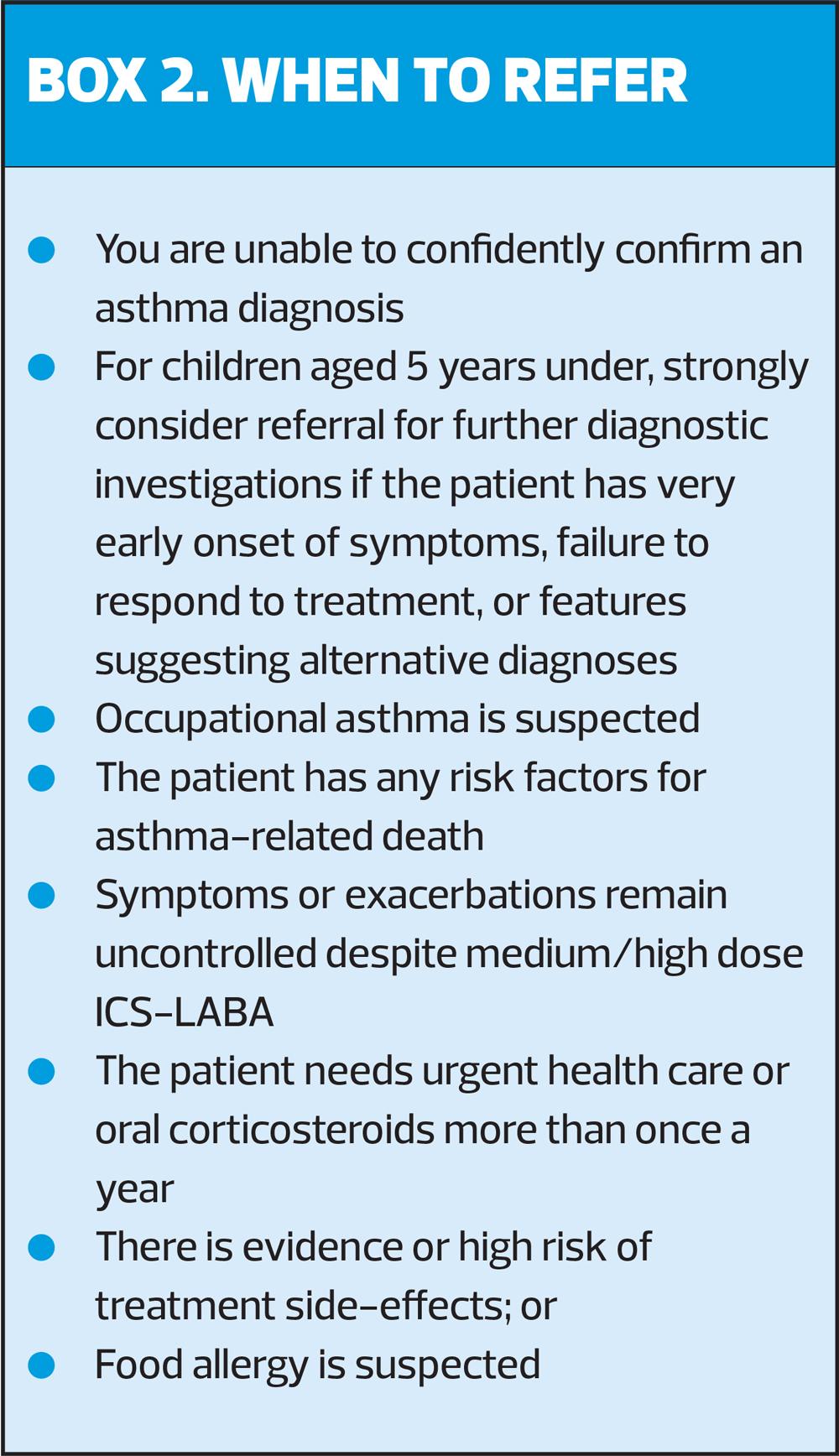

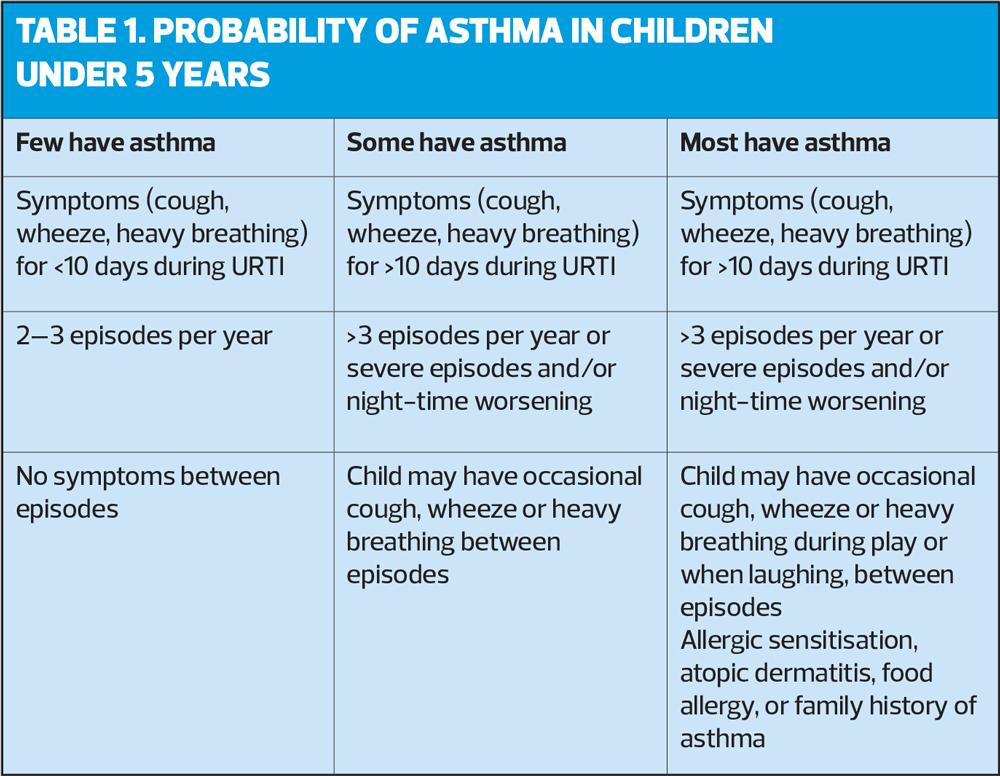

DIAGNOSIS IN CHILDREN

5 years and younger

It can be difficult to diagnose asthma in children under 5 because episodic respiratory symptoms (e.g. wheezing, cough) are also common in children without asthma. A probability-based approach, based on the pattern of symptoms during and between viral upper respiratory tract infections (URTI) may be helpful in discussions with parents, and allows individual decisions to be made about whether to give a trial of ICS. It is important for the clinician and the parents to make decisions for each child individually to avoid over- or under-treatment.

6 years and older

Making the diagnosis of asthma in older children follows the same approach as used in adults, and is based on identifying both a characteristic pattern of respiratory symptoms – wheeze, shortness of breath, chest tightness or cough, and variable expiratory airflow limitation. When the child has symptoms, confirm that FEV1/FVC is reduced (according to GINA, >0.90 in children, compared with >0.75-0.80 in adults). In children, a positive bronchodilator reversibility test results would be an increase in FEV1 of >12%. Variability in airflow limitation can also be shown with twice daily peak expiratory flow (PEF) over 2 weeks: in children, average daily diurnal PEF variability >13% would support a diagnosis of asthma.

If possible, evidence supporting the diagnosis should be documented when the patient first presents with symptoms, as characteristic features may improve spontaneously or with treatment and it is more difficult to confirm the diagnosis once the patient has started ICS.

CONCLUSION

In the absence of up-to-date UK guidance and the prospect of a long wait for current guidelines to be updated, it seems that general practice nurses need to look further afield for best practice. The GINA 2021 report is based on a review of the latest evidence, and reinforces the importance of ensuring patients with a confirmed asthma diagnosis receive adequate controller therapy. This means that virtually all patients with asthma should be prescribed at least a low dose ICS, and that no one should be treated with SABA alone.

This summary aims to provide the main recommendations new to 2021, but we would urge you to read the full report, at https://ginasthma.org/wp-content/uploads/

2021/05/GINA-Main-Report-2021-V2-WMS.pdf. There is much of value to be found.

REFERENCES

1. British Thoracic Society/Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (BTS/SIGN). British Guideline on the management of asthma; 2019. https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/quality-improvement/guidelines/asthma/

2. NICE NG80. Asthma: diagnosis, monitoring and chronic asthma management; 2017 (updated 2021). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng80

3. BTS. BTS, SIGN and NICE to produce joint guideline on chronic asthma as part of broader ‘asthma pathway’; 24 July 2019. https://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/news/2019/bts-sign-and-nice-to-produce-joint-guideline-on-chronic-asthma/

4. Marsh V. Asthma in children and young people: an update. Practice Nurse 2021;51(8):15-20

5. Global Initiative for Asthma. 2021 GINA Report, Global strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention; 2021. https://ginasthma.org/gina-reports/

6. Dusser D, Montani D, Chanez P, et al. Mild asthma: an expert review on epidemiology, clinical characteristics and treatment recommendations. Allergy 2007;62:591-604

7. Hancox RJ, Cowan JO, Flannery EM, et al. Bronchodilator tolerance and rebound bronchoconstriction during regular inhaled beta-agonist treatment. Respir Med 2000;94:767-71

8. Aldridge RE, Hancox RJ, Taylor DR, et al. Effects of terbutaline and budesonide on sputum cells and bronchial hyperresponsiveness in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2000;161:1459-1464

9. Royal College of Physicians. National Review of Asthma Deaths: Why asthma still kills; 2015. https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/why-asthma-still-kills

10. Wilkinson AJK, Menzies-Gow A, Sawyer M, et al. BTS Oral abstract S26. Thorax 2021;76 (Suppl 1). https://thorax.bmj.com/content/76/Suppl_1/A19.1

11. Amin S, Soliman M, McIvor A, et al. Understanding patient perspectives on medication adherence in asthma: a targeted review of qualitative studies. Patient Prefer Adherence 2020;14:541-551

12. O’Byrne. Lancet Respir Med 2021

13. Price DB, Trudo F, Voorham J, et al. Adverse outcomes from initiation of systemic corticosteroids for asthma: long-term observational study. J Asthma Allergy 2018; 11:193-204